The Shakers reached their heyday in the nineteenth century, when they lived in orderly communities, membership swelled to five thousand believers, and many non-Shakers visited them and praised their modesty, neatness, and productivity. But Shakerism in America began against the backdrop of the Revolutionary War, and during that time the group of celibate and intensely religious adherents was first ignored, and then feared, jailed, hated, and beaten as they spread their views and recruited new members. The suspicions of wartime almost destroyed the Shakers, who openly preached pacifism and were also repeatedly accused of being British agents, yet the unsettled conditions in America also aided their cause, as many war-weary and desperate colonists wanted spiritual and moral fulfillment in this life and salvation in the next. By the war’s end, the Shakers had established a following, and they would continue to grow under the religious freedom guaranteed in the young republic.

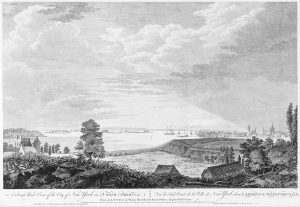

According to official Shaker accounts, their sect first flourished in England in the city of Manchester by the 1740s, led by James Wardley and his wife, Jane. One of their young adherents was local resident Ann Lee, who joined the group in 1758.[1] They were sometimes called “Shaking Quakers,” and became known as Shakers for short, a moniker they came to accept in addition to the more formal United Society of Believers. Because of a dearth of followers, and on account of arrests, physical abuse, and others persecutions, some Shakers, all English, emigrated to America, arriving in Manhattan on August 6, 1774. They included, again according to Shaker accounts, Ann Lee; her husband, Abraham Stanley (Standerin in some documents); her brother and niece, William Lee and Nancy Lee; Mary Partington; John Hocknell and his son Richard Hocknell; James Shepherd; and James Whittaker. They were going against the grain in a political sense as well as a religious one: while many, especially those loyal to the Crown, were fleeing America, the Shakers voyaged into a tumultuous environment, the air thick with talk of revolution and war. The Intolerable Acts had been passed earlier in the year, and the First Continental Congress would meet in Philadelphia a month after the Shakers’ landing. Early Shaker Daniel Goodrich wrote in 1803 that the group arrived in “New York at the Time our Citys and C[o]untrey was in utmost Confusion and Alarm of War.” Goodrich asserted that the peace-loving Ann Lee was “Litterley unaccustomed with such things,” and the elders in the group had to explain to her that the confusion and upheaval were owing to the “preparations for war with England.”[2] They at first resided and worked in various locations, and Ann Lee herself worked at menial jobs in Manhattan. Shepherd and Stanley did not stay with the group for long, after which the latter’s wife dropped her married name for good and went by Ann Lee. The motley group of Shakers, most of them poor and with little education, got a boost from John Hocknell, a person of some economic means, who purchased land for the group at Watervliet (also called Niskeyuna), near Albany. Hocknell, returning briefly to England, brought his family to America. The husband and children of Mary Partington also came to America.

The Shakers were relatively quiet for the five years after their first arrival. The first period of the expansion of Shakerism in America was 1770-1783, a time in the Hudson Valley of war-weariness, economic difficulty, and normlessness. The whole region, the city of New York to Albany, was highly contested and especially fraught with anxiety. Manhattan was occupied by the English early on in the war. Above it, the neutral ground in what is now the Bronx and Westchester County remained in large part a military no-man’s-land and a place of retribution and strife. North of that, huge chains across the river were maintained to keep British ships bottled up to the south, and the shores of the Hudson are dotted with battle sites, including Fort Montgomery, Peekskill, and Stony Point, as well as that famous scene of treachery, West Point. Sprinkled throughout the Hudson Valley, and in especially large numbers in the Albany area, was a large population of Dutch-Americans, many of whom, clinging to their language and customs, were little interested in the war, and were often accused by Anglo revolutionaries of indifference or even of betraying the cause by trading with the English. Canada was always looming to the north, and attacks from there could never be ruled out. Native American tribes supporting the British lived and operated nearby, just west of the Hudson and beyond.

In this tense region, local “Commissioners for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies,” appointed by the government of New York, kept a sharp eye open for disloyalty and treachery. The rag-tag group of Shakers ran into problems because of their pacifism: here was a group of British citizens, suspiciously arrived during the revolutionary period, going about with their strong English accents telling Americans that it is God’s will that they lay down their arms and cease battle against the British. As noted in the minutes of July 7, 1780, the commissioners at Albany had received a report that some Shakers, because of their “disaffection to the American Cause,” were driving sheep westward to “convey them to the Enemy or at least bring them so near the Frontiers that the enemy may with safety take them.” The Shakers finally proved “Satisfactorily to us that they had no intention of driving the said sheep to the Enemy,” but the commissioners openly objected to the Shakers’ “determined Resolution never to take up arms and to dissuade others from doing the same,” and concluded that “such principles at the present day were highly pernicious and of destructive tendency to the Freedom & Independence of the United States of America.”[3] It was the political attitudes and denial of local authority of the Shakers that brought them trouble at this time, and not their belief that sexual intercourse was a sin; nor that they shook and danced convulsively in religious ecstasy; nor their obsession with order and cleanliness; nor the idea that Christ had appeared again in the person of Ann Lee nor that the Shakers associated her with the woman clothed in the sun described in Revelation 12:1.[4] The theology could be ignored, but the calls to lay down arms and the appearance of suspicious trading and spying drew official action. Ann Lee and some other leading figures in the sect were arrested and jailed in Albany. An account by Shaker Daniel Goodrich (1803) explained that the commission thought “they weare Imisareys [emissaries] from Great Briton Sent to overthrow the Cause of Liberty as they termed it; which they ware Fighting for.”[5] Note, even long after the Revolution, the sarcastic tone of Goodrich’s mention of “Liberty.” Apostate Valentine Rathbun had heard a Shaker say of the Patriots in 1780 “that all our authority, civil and military, is from hell, and would go there again.”[6] The Shakers did not think much of war and were unimpressed with the thirst for liberty and the political and moral claims made by American colonists.

In the important Shaker history and manifesto of 1816, Rufus Bishop and Seth Wells insisted in the Testimonies that the Shakers were innocent of the charges of supporting Great Britain, and they described the imprisonment of Lee and others in Albany: “after a short examination, in which they were charged with being enemies to the country, and yet, without the smallest degree of evidence, they were also committed to prison. They were first put into the jail of the old City-hall; but after a few days, they were removed to a prison in the old fort, just above the town, where those who were called tories, and other prisoners of war were generally confined.” Soon, all but Ann Lee, the clear leader of the sect, was released. A rumor went about among the Shakers that the commission had an idea to solve their problem: “the elect Lady [Mother Ann] is going to be sent to the British army, at New-York, and [it was] intimated that the [Shaker] people would all be broken up.”[7] Ann Lee was jailed further south, in Poughkeepsie. Then, rather than being sent down to the English, who may or may not have wanted to receive her, Mother Ann was released and returned to Watervliet, the authorities apparently having come to believe that, at least, she was no spy or agent on behalf of the British.

For over five years in America, Shakers had labored to get by, and they kept waiting for their message to gain a following, but hope was beginning was fade. Bishop and Wells wrote that “those who came to America with Mother, had great expectations that the gospel would soon open in this country.… But after waiting several years, without the addition of a single soul to the faith, they were all, excepting Mother, brought into great trials and doubts respecting the opening of the gospel.”[8] They languished until early 1780, when they gained converts from among some evangelicals in the area engaged in a popular New Light “awakening.” A local center of this movement was New Lebanon, a town in New York on the border with Massachusetts. With their own awakening petering out, some of those affected, one by one, heard of the Shaker sect and the holy woman Ann Lee, and came to Watervliet in a fervor. They visited her and the other Shakers, and several early accounts, some written by later apostates, indicate the powerful effect that Ann Lee and the others had on this hopeful stream of visitors.

Valentine Rathbun, who first encountered Ann Lee and the Shakers in Watervliet, published his account in 1781, and dated it December 5, 1780, putting him right near the beginning of the expansion of the sect. Rathbun’s account, although written at that point as an anti-Shaker, comes across as believable: “They bid him [the new visitor] welcome, and directly tell him they knew of his coming yesterday.” Rathbun noted that this uncanny prescience “sets the person a wondering at their knowledge.” Then, before any verbal proselytizing begins, the Shakers “sit down and have a spell of singing; they sing odd tunes, and British marches, sometimes without words, and sometimes with a mixture of words, known and unknown.”[9] Their methods were successful in getting a psychological hold on the visitors. Another apostate, Hervey Elkins, had talked to early Shakers and concluded of Mother Ann that “there can be no dispute but that she possessed a tremendous psychological and clairvoyant power; and was a lady of great mental and physical talent.”[10]

Apart from the charisma of Ann Lee and the Shaker techniques of persuasion, why did the Shakers have such success at this time? Shaker Calvin Green expressed his opinion in 1827 that the American Revolution was corrupt and vile, but he also, writing with insight, recognized that weariness and disgust with the war encouraged some to religious ferment, and then from that awakening they turned to the Shakers:

About the middle of the Revolutionary war, the people of America, seeing war and bloodshed prevail among the professed followers of Christ, and seeing them biting & bickering one another; and those who professed to be Brethren, and followers of the Prince of Peace, destroying[,] ravaging & rendering each other miserable as was in their power, many were led to believe that the very foundation of such professions was corrupt and rotten. Hence their minds were stirred up to search after something better. From [these] things [that is, the stress and devastation of wartime], prayers, exortations [sic] and religious awakenings succeeded.[11]

He saw the evangelical ferment in the area as a result of war weariness and disgust, but we can go a step further and also see the interest in the Shakers as a product of the same sense of longing for something better than a war-ravaged world.

Hoping to gain even more converts, Ann Lee and several others left the Hudson Valley and went east into what turned out to be hostile terrain. Beginning in May 1781, they undertook a preaching and proselytizing tour through New England that lasted two years and three months. The communities in New England were tightly controlled, and probably more supportive of the Revolution than the towns of the Hudson Valley, and the Shakers often met with violent resistance. Locals did not like that the Shakers effectively wanted to break up marriages and add property to their communal holdings, and it was also feared that the Shakers were poor vagrants who would settle and become a burden by needing public assistance. Above all, again, the Shakers were thought to be not only pacifists, but armed agents working on behalf of the enemy. With their English accents, and occasionally singing “British marches,” as Rathbun noted, the Shakers received the wrath of the supporters of the Revolution.[12]

In town after town, either officials or self-appointed mobs would meet the Shakers and warn them out or confront them. When the Shakers did enter a town, they were often physically abused. The charges of treachery continued, as when “sometime in the later part of July [1781]…. a report was circulated in Harvard [Massachusetts], that the Shakers had come there with seventy waggons, and six hundred stands [open barrels] of arms; that they were enemies to the country, and had come to aid the British in the war against America.” Throughout the towns in Massachusetts, they were accused of being fake pacifists and of actively opposing the American cause by bringing with them concealed stashes of “fire-arms and implements of war.”[13] Remarkably, at Ashfield, Massachusetts, in 1783, a mob “concluded that Mother’s pretentions were an imposition [imposture] upon the people, and strongly suspected her to be a British emissary, dressed in women’s habit, for seditious purposes.”[14] They could not believe that a woman might be a successful ringleader, and they suspected that this “Ann Lee” was actually a man. They seized her, and she was rudely and intimately inspected by two local women, who confirmed that she was indeed no male! During these years of travel and proselytizing, the Shakers were denounced, beaten, and dragged about in various places, and a later Shaker revision of the Testimonies provided gruesome details of the early suffering, as at Shirley, Massachusetts, in June 1783:

[The mob] then seized Elder James, tied him to the limb of a tree, near the road, cut some sticks, from the bushes, and Isaac Whitney, being chosen for one of the whippers, began the cruel work, and continued beating and scourging till his back was all in a gore of blood, and the flesh bruised to a jelly. They then untied him, and seized Father William Lee; but he chose to kneel down and be whipped, therefore they did not tie him; but began to whip him as he stood on his knees. Notwithstanding the severity of the scourging which Elder James had already received, he immediately leaped upon Father William’s back, [and] Bethiah Willard, who had followed from Jeremiah’s, leaped upon Elder James’ back; others, who came with Bethiah, followed the same example. But, such marks of genuine Christianity only tended the more to enrage these savage persecutors, and those who attempted to manifest their love and charity in this manner, were inhumanly beaten without mercy.[15]

The Shakers came to regard these as acts of martyrdom. When the body of Ann Lee and two Shakers were exhumed in 1835 at Watervliet, signs of this early abuse were deemed worthy of comment: “Some marks of their sufferings were yet visible. – On the left side of Mother’s scull could be seen a fracture, said to be made [in 1781] when she was dragged downstairs feet foremost by her persecutors when at Petersham [Massachusetts].”[16] The trip to New England provided the Shakers with material for a history of heroic and saintly suffering.

By the time the trip to New England ended (July 1783), the Shakers had established a firm following. The little band of missionaries returned to Watervliet, and the peace treaty with Britain was signed later that year. Ann Lee died in September 1784, at the age of 48. A hero of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette, happened to visit Watervliet soon after her demise, along with François Barbé–Marbois (later Marquis de François Barbé-Marbois), the secretary of the French legation to the United States. Lafayette was fascinated by hypnotism, and was interested in studying the Shakers first-hand, “desiring to examine at close range phenomena which have a great similarity to those of ‘Mesmerism’.” The visitors learned that Ann’s death surprised and embarrassed her followers, who had believed her to be immortal.[17] Even without the Elect Lady leader, the sect lived on, and continued to grow in the new nation. The Shakers had come into conflict with local populations during the war, but one could also argue that in some of their attitudes they embraced ideals shared by other late-eighteenth-century Americans, including supporters of the Revolution. The Shakers emphasized hard work and industry; were suspicious of central political authority; were in their own way optimistic; and believed in self-improvement and the self-reliance of communities. They did establish a hierarchical authority in their villages, but they were also, arguably, forward-looking in admiring and obeying a woman and, soon, allowing women a role in the governance of Shaker communities.

Despite the early struggles, the Shakers were happy to claim later that they had always had an American destiny. Shaker leader James Whittaker, one of the founding members of the group in America, was said to have had a vision back in England during the time of tribulation and persecution there, “While I was sitting there, I saw a vision of America, and I saw a large tree, and every leaf shone with such brightness, as made it appear like a burning torch, representing the Church of Christ, which will yet be established in this land.”[18] Similarly, Calvin Green wrote in 1827 that “Mother Ann frequently prophesied of the gathering [of] the Church in Gospel Order; but that it would not be her lot, nor that of any who came from England to gather the church, but it would be the lot of [American] Joseph Meacham.”[19] Thus, Ann Lee was said to have prophesied that it was an American who would lead the group to order and greatness. Indeed, her successor as recognized head of the church, Englishman Whittaker, died in 1786, and it was Americans Joseph Meacham and Lucy Wright who established the rules and order that we associate with the structure of Shaker society: villages isolated from the world’s people; instructions and dogma emanating from a central ministry; rule over the communities by a system of elders, eldresses, ministers, trustees, deacons, and deaconesses; residential isolation of men from women; and controlled contact between the sexes during daily life. Whatever Shakerism there had been in England petered out, and the Shakers embraced their American home in well-ordered communities, their freedom of belief protected by law.

During “Mother Ann’s Work” of the 1830 and 1840s, a period of numerous mystical visions and particularly ecstatic worship, many Shakers experienced dreams and visions of angels, dead Shakers, and historical and religious figures, and among the occasional luminary visitors during this period was General Washington.[20] George Washington, a believer in just wars if ever there was one, finally became a friendly visionary spirit to at least some Shakers. But opposition by the pacifistic Shakers to the Revolution never completely waned. Rufus Bishop, a leader of the central Shaker community of New Lebanon, New York, would often note in his journal the occasion of the Fourth of July, and more than once he made disparaging remarks about the national celebration, which the Shaker communities did not embrace. His journal entry on Independence Day, 1836 records the lingering bad feeling of the Shakers towards the American Revolution, and we can close here by letting Bishop have the last word: “Foggy, Cloudy & falling weather, & towards night a powerful shower, rather disappointing to the children of this world who feel anxious to manifest their Independence! Poor inconsiderate mortals! they had much better humble themselves & manifest their dependence upon God.”[21]

[1] There is a prodigious bibliography on the Shakers. For a good overview, see the text and bibliographic notes in Stephen J. Stein, The Shaker Experience in America: A History of the United Society of Believers (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992). For an official account by the Shakers of their formative years, see Rufus Bishop and Seth Y. Wells, Testimonies of the Life, Character, Revelations and Doctrines of our Ever Blessed Mother Ann Lee, and the Elders with Her: Through Whom the Word of Eternal Life was Opened in this Day of Christ’s Second Coming (Hancock, MA: J. Tallcott & J. Deming, Junrs., 1816), 1-15.

[2] Daniel Goodrich, “The Rise and Progress of the Church” [alternate title: “Narrative History of the Church”], 1803, The Amy Bess and Lawrence K. Miller Library, Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 4.

[3] See Victor Hugo Paltsits, ed., Minutes of the Commissioners for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies in the State of New York. Albany County Sessions, 1778-1781, 3 vols. (Albany, NY: State of New York, 1909-1910; reprint Boston: Gregg Press, 1972), vol. 2 [1909], 452-453. See also the discussion in Steiner, The Shaker Experience in America, 13.

[4] See Linda Mercadante, Gender, Doctrine, and God: The Shakers and Contemporary Theology (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1990), for a discussion of the theological and gender issues surrounding the person of Ann Lee; see also Tisa J. Wenger, “Female Christ and Feminist Foremother: The Many Lives of Ann Lee, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 18, no. 2 (Fall, 2002): 5-32.

[5] Goodrich, “The Rise and Progress of the Church,” 6.

[6] Valentine Rathbun, An Account of the Matter, Form, and Manner of a New and Strange Religion, Taught and Propagated by a Number of Europeans living in a Place called Nisqueunia, in the State of New-York (Providence, RI: Printed and Sold by Bennett Wheeler, 1781), 12. Rathbun gave his title as “Minister of the Gospel” to underscore his own credentials.

[7] Bishop and Wells, Testimonies, 73.

[8] Bishop and Wells, Testimonies, 13.

[9] Rathbun, An Account of the Matter, Form, and Manner of a New and Strange Religion, 4.

[10] Hervey Elkins, Fifteen Years in the Senior Order of Shakers: A Narration of Facts, Concerning that Singular People (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth Press, 1853), 18.

[11] Calvin Green, “Biographical Account of the Life, Character and Ministry of Father Joseph Meacham, the Primary Leader in Establishing the United Order of the Millennial Church,” 1827 [copied from the original by Elisha D. Blakeman, May 1859], New York Public Library, Shaker Manuscript Collection (#110), 3.

[12] Rathbun, An Account of the Matter, Form, and Manner of a New and Strange Religion, 4.

[13] Bishop and Wells, Testimonies, 87 and 108.

[14] Bishop and Wells, Testimonies, 140.

[15] Rufus Bishop, Seth Youngs Wells, and Giles Bushnell, Testimonies of the Life, Character, Revelations and Doctrines of Mother Ann Lee and the Elders with Her, 2nd edition (Albany: Weed, Parsons and Co., 1888),119-120.

[16] Asenath Clark, “Ministerial Journal, 1834-1836,” The Amy Bess and Lawrence K. Miller Library, Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, Mass., p. 24 (11 May 1835).

[17] See Eugene Parker Chase, ed. and trans., Our Revolutionary Forefathers: The Letters of François, Marquis de Barbé-Marbois during his Residence in the United States as Secretary of the French Legation 1779-1785 (New York: Duffield and Co., 1929), 180-181.

[18] Bishop and Wells, Testimonies, 66.

[19] Green, “Biographical Account,” 12.

[20] A useful study of this phenomenon is Sally Promey, Spiritual Spectacles: Vision and Image in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Shakerism (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993).

[21] Rufus Bishop, “A Daily Journal of Passing Events,” vol. 1 (of 3), 4 July 1836 (no page numbers), New York Public Library, Shaker Manuscript Collection (# 1).

3 Comments

Great research about a little-written-about side of the Revolution. There’s a book out there about how the Revolution affected pacifist sects: Quakers, Shakers, Moravians, etc.

Dear Don: Thanks for your kind comment. Yes, lots of interesting issues and tensions to consider concerning the Revolution and pacifists in the thirteen colonies.

Fascinating article! I wonder what the Watervliet Shakers would think about the Watervliet Arsenal!