On September 11, 1780, a detachment of forty-one Northampton County, Pennsylvania, militiamen was surprised by a force consisting of thirty Seneca warriors and Tories. When the fighting was over, fifteen American patriots lay dead on the ground.”[1]

“As the summer of 1780 began to wane, a detachment of forty-one of the veteran Van Etten’s Company was assigned to an imposing twenty-five year old Captain named Daniel Klader. Klader would lead these men into hostile and physically demanding terrain on a mission that culminated in tragedy.[2]

These two quotes, taken from Rogan H. Moore’s book (which many historians consider to be the modern day authoritative source on the Sugarloaf Massacre), demonstrate what can happen when myth and folklore transition into historical memory. Some facts aren’t in dispute, of course. In early September 1780, a detachment of volunteer militia did venture into the northwestern frontiers of Northampton County as part of an ongoing frontier war with the natives and Tories. On September 11 they were attacked and defeated along the Little Nescopeck. There is even a monument at the site with a bronze plaque, listing fifteen names of those soldiers who supposedly died at the site, placed there in 1933 by the local chapters of the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution. A little further back is a headstone inscribed with the name ”Daniel Klader, Captain, Van Etten’s Co., Northampton Co. Militia, Died 1780.”

However the event itself has raised many questions because of the limited scope of the resources about the events. What exactly was this detachment doing in this part of the wilderness? Who was leading it? Why had they been so soundly defeated? Did fifteen men really die during the battle? Well, the answers aren’t as readily apparent as Moore suggests. In fact, Moore gets a great deal wrong. To be fair, it isn’t necessarily Moore’s fault. Moore’s narrative about the Sugarloaf Massacre has dominated the retelling precisely because he is using a narrative that goes back generations. The resources he used are themselves terribly unreliable. From printed articles full of wild local lore from the end of the nineteenth century to books on the region’s history written by historical societies of the 1920’s, it is hard to find a careful examination of this massacre anywhere. Let’s remedy that.

After the Wyoming and Cherry Valley Massacres, Washington commanded General Sullivan to launch a brutal scorched-earth campaign against the Indians.[3] It was the hope of Washington, Sullivan, and the backcountry inhabitants of Pennsylvania’s frontier that this campaign would drive the Indians out of reach of the homesteads and plantations; their close proximity had made it easy to launch attacks and raids on the civilian populations for generations (it didn’t help that settlers continued to encroach upon American Indian land granted under treaty).

For the most part, the Sullivan campaign only fueled the Indian and Loyalist resolve to continue their raids. These attacks were continuous throughout the years of 1778[4] and 1779. Repeated requests for help were largely ignored by President Joseph Reed in Philadelphia[5] and when Sullivan was asked for aid, he saw his campaign as the greater importance and refused.[6] Even after attacks on defensive stations like Fort Freeland, in Northumberland County, in which a militia garrison was attacked and defeated, no help was granted.[7]

Following Sullivan’s campaign, things quieted down primarily due to the coming winter season. But with spring, things began to heat up once more. On April 27, 1780, Lt. Col. Nicholas Kern, a veteran of the current war who had barely escaped capture at the Battle of Long Island in 1776,[8] hurriedly scribbled a note to Samuel Rea, County Lieutenant. In his note, he relayed information about a new incursion. Apparently he wrote so fast that he did not have time to think about spelling (he was in the danger zone):[9]

Excuse haste, we have this meiunet returned from a scout, where we found mr. Benjamin Gilberts house And gice mill & saw mill totally consumed with phire, and likewise Benjaman Peirts house, and the people Carryed of prisoners fifteen in Number by the enemy… We have had some scouting partyes But as Vallenteers will not stay above two or three Dayes from home at once, it is of no use to the inhabitants as security.

On May 1, Rea forwarded on this news to Reed, telling him that he planned to call up an additional company of militia to secure the frontiers. Things in Northampton County were falling apart. Rea stressed that though the time had come to elect new officers for the militia, the commissions had come in late from the state, so he had not yet had time to arrange elections. Without officers, the militia could not be called. It didn’t help that the officers were themselves discipline problems.[10] Reed’s response underscores the reputation that the drafted militia from Northampton County had gained:

We observe you have called the Militia which we approve provided they will seriously employ themselves in their proper Duty but we must express our Disapprobation of their rendezvousing in Large Bodies in Taverns & spending their time in Amusements.[11]

In the same letter, Reed reassured Rea that the measures taken by the Supreme Executive Council would help ease the burden of the county by reinstating the scalp bounty, as indicated above, but also by an additional measure:

We have concluded to raise a Company immediately upon the Terms proposed in the enclosed Papers, & that no Time may be lost, we desire you…to appoint the Officers agreeable to the Plan inclosed, & set them immediately to recruiting Men.

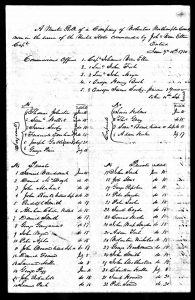

The plan to which Reed refers was an ordinance passed in the Council on May 10, 1780 called ”An Act for the Greater Ease of the Militia and the More Speedy and Effectual Defence of this State.” This ordinance called for the establishment of a single company of volunteers, to be distinguished from the drafted militia, that would serve not less than seven months, from the middle of June to the middle of January, and would be outfitted, then ordered out to deal with the threats to the north. Rea apparently met his quota in time to organize the company according to the ordinance, as the muster roles indicate that the company formed on June 15, 1780.[12]

On July 4, Rea was making progress:

I have filled up the Commissions for the following officers, Viz., Capt. Johannes Van Etten, Lieutenant John Fish, and Ensign Thomas Syllaman. According to orders I have collected the Volunteirs at the County Town, and find that there is but fifty, but they are dayly Comeing in. I have ordered them up to the frontier of this County.[13]

Johannes Van Etten had organized a defense against the raid a few weeks previous, mentioned above. But just who was Johannes Van Etten? According to a document in one of the John Van Etten pension files, “There are several of the name in the service, and we are having difficulty in identifying ours from the others.”[14] This is problematic for most people engaged in ancestry research, but for someone trying to pinpoint which officer was where and who did what task, it means tedious work. Moore apparently made the mistake that many do—conflating multiple individuals with the same name as if they were all one person.[15] Moore writes, for example, that “Captain Van Etten, the son of Jacob Van Etten…served with distinction during the French and Indian War.” Yeah, no, that isn’t correct.

See page 2. See page 3.

While Johannes Van Etten was no slouch when it came to fighting on the frontier, he was not a Captain during the French and Indian War; that was his brother John.[16] In fact, Johannes Van Etten was a member of his brother’s ranging company, commissioned in Northampton County by Benjamin Franklin, during that war.[17]

Around the time that the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, John moved away with his family; to where and at what time of the year, it is unclear (but he no longer shows up in Northampton County on tax records after that period).[18] By late 1777, after the Militia Law was passed, Johannes finally shows up on returns as an elected Captain of a militia company in the northern militia district (or the 6th Battalion District in 1777).[19] Whether he saw service during the Philadelphia Campaign is unclear, though again we have an instance of rumor and folklore.[20]

Regardless, he had proven his determination in the defense of the frontiers. He had even turned his home into a garrison for the purpose of providing a safe haven for the region. Thus Van Etten was elected as the captain of volunteers for the county of Northampton. But what would be the purpose of the volunteers? Where were they going and what would be their task?

Disaffection ran high in Northampton County, but after Sullivan’s campaign, those most agitated with constantly being disarmed and taxed removed themselves to the furthest parts of the county, in the area known as Fishing Creek and Catawissa.[21]

When Lt Col. John Butler began recruiting for the crown in 1778, he found more than enough to fill his ranks from these regions. Those who did not elect to fight were more than happy to shelter Indians loyal to the crown and pass along Patriot militia movements and intelligence as they came to hand. As early as April, hunters were complaining of the discharging of guns in the wilderness near Fishing Creek.[22] Shortly after, Tories and Indians were raiding the countryside using the northern regions of Northampton and Northumberland, using Catawissa and Black Creek as a base of operations as they had during the French and Indian War.

Reed firmly believed that routing these inhabitants and depopulating the region, either by force or through harassment, was the key to lasting security for the well-affected frontier communities.[23] It was the hope that the Seven Months Men, as they were called, would discourage the raids.

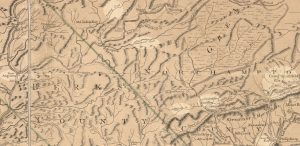

According to the pension file of Henry Bush, an ensign in the company, Van Etten’s men first marched from Easton to Stroudsburg (named after Colonel Stroud), likely staying at Fort Penn or Fort Hamilton as a garrison for about two weeks. From there they marched to Fort Allen.[24] At this point the company broke into detachments to garrison different defensive forts and block houses. In one of the most erudite and comprehensive (and accurately recollected) pension depositions I’ve come across, Henry Davis, another member of the Company and survivor of the massacre, dictated:

The Declarant further states that on the fifteenth day of June AD 1780 he entered the United States service as a volunteer in the (5th) fifth company of the third Battalion of Northampton County Pennsylvania Militia under Captain Vannata (or Vannaten) and that he served in said company until the fifteenth day of the next January 1781 making seven months and that he got no discharge when he left the service. & that John Fish was first and John Myers was second Lieutenant in the company, Nicholas Carns [Kerns – ed.] ye Major (as he thinks) and John Sigfreit was Colonel [it was the other way around – ed.] part of the time and Brown a part. That he was in one battle with the Indians commonly called the Seven Months Battle—in the Nescopeck Valley in Pennsylvania that he resided in Northampton County when he entered the service this time, marched along the frontiers of the North East part of Pennsylvania—lay part of the time at Gnaddenhutten and part at a place called the Minnysinques [the Minisink-ed.] and part of the time at Captain Vannata’s fort at his own house in Pennsylvania.

In early September, Van Etten’s men went on the offensive. Moore incorrectly suggests that Colonel Hunter placed an individual named Daniel Klader in charge of this offensive detachment, apparently magically giving him a commission as Captain.[25] But according to Samuel Rea, the detachment marched out from Gnaddenhutten on September 8 seemingly at Rea’s orders, not Hunter’s (which makes sense because a colonel from Northumberland had absolutely zero authority over the county lieutenants or the militia of Northampton), to begin their trek into the Sugarloaf Valley:

Having had Sundry alarms & small parties of the Enemy having made incursions into the remote parts of it who plundered & burnt several Houses we thought it our indispensible Duty to send out a part of men as a Scout which consisted of forty one men part Militia & part of the Volunteers…to make such Discoveries as they could, and examine into the Reasons why a Number of Families on the Enemies Boarders remain on their Farms without Molestation or apprehension and give us information of the same, who accordingly marched from Canaudenhutten (a small old Moravian Town Situated behind the Blue Mountains on the west Branch of the Delaware) on the Eighth Inst.[26]

Of the battle, there exists only one contemporary eyewitness account. In the pension deposition of Peter Krum, a private in the company, it states that:

A part of the company was sent to Black Creek to which he belonged. The Captain and Lieutenant went along, when they reached Black Creek they were attacked by the Indians and they were defeated. There were of their company…seven killed and three prisoners taken. The lieutenant was one of the prisoners…the Indians attacked them while eating dinner, the balance retreated about as he supposes twenty miles…He remained there on the frontier until his term of service was expired without any other engagements.. He states he served a full term of seven months and returned home in the winter, or he can say it was cold weather.

The first report of the attack came on September 14. The event was recorded in a diary of one of the soldiers stationed at Fort Allen:

Lieutenant Myers, from Fort Allen, came into the Fort, and said he had made his escape from the Indians the night before, and that he had been taken in the Scotch Valley, and that he had thirty three men with him, which he commanded. He was surrounded by the Indians, and thirteen of his men killed, and three taken.[27]

Samuel Rea wrote to President Reed on September 17 with the news:

[Van Etten’s men] were attacked on the Eleventh at the Nusquepeck by a party of whitemen and Indians who had the advantage of first fire on our men which obliged them to retreat. The Enemies loss we cannot ascertain but the wounded & missing of ours, amount to twentythree, four of former [wounded] and Nineteen of the latter [missing]. On the fifteenth a Number of Militia and Volunteers to the amount of one-hundred or upwards marched with a Design if burying the Dead & making such observations as might lead to a Discovery of the Enemies Number or Design.[28]

The situation was so confused that no one had a good grasp of how many were killed, wounded, or missing. A few days later, on September 20, Lt. Col. Stephen Balliet gave his account of the burial detail and what he had discovered:

Sir, I take the earliest opportunity to acquaint your Excelency of the…Misfortune Happened to our Volunteers stationed at the Gnaden Hutts. They having Rec’d Intelligence that a Number of Disaffected Persons lived near the Susquehannah at a place called the Scotch valley, who have been suspected to hold up a correspondence with the Indians, and the Tories in the country. They sat out on the 8th Ins’t for that Place to see whether they might be able to find out anything of that nature, but were attacked on the 10th at noon about 8 miles from that settlement by a large Body of Indians & Torys (as one had Rid hair,) Supposed by some forty & by others twice that number they totally Dispersed our People, Twenty two out of forty one have since come in several of whom are wounded. It is also Reported that Lieu’t Jn’s Moyer had been made Prisoner & made his escape from them again & Returned at Wyoming. On the first notice of this unfortuned event the officers of the militia have Exerted themselfs to get Volunteers out of their Respective Divissions to go up & Burry the Dead, their Labour Proved not in Vain we collected about 150 men & officers Included from the Colonels Kern, Giger & my own Batallions who would undergo the fatique & Danger to go their & pay that Respect to their slautered Brethren, Due to men who fell in support of the freedom of their Country. On the 15th we took up our line of march (want of amunation prevented us from going Sooner) on the 17th we arrived at the place of action, where we found Ten of our Soldiers Dead, Scalped, Striped Naked, & in a most cruel & Barborous manner Tomehawked, their throads Cut, &c. &c. whom we Buried & Returned without even seeing any of these Black alies, & Bloody executors of British Tirany…. We also have great Reason to beleve that several of the Indians have been killed by our men, in Particular one by Col. Kern & an other by Capt. Moyer both of whome went Volunteers with this partie.[29]

First, note that while many were wounded, Balliet—a man who oversaw the burial detail of the dead—counted only ten bodies. Second, Lieutenant Moyer was captured, but escaped. Third, Captain Moyer—undoubtedly William Moyer, father of Lieutenant John Moyer, who served as captain in the militia during this period—went as a volunteer to the area to help bury the dead. All of this is important because as we move forward, we will be referencing these details.[30]

So now for the million dollar question: Just who led the expedition? This is where our primary source data becomes scarce and where we really start to get the most bizarre instances of mythological contamination in the narrative. Returning to our most recent historical interpretation by Mr. Moore, as quoted above, it was Daniel Klader. There is, after all, a headstone and a monument with Daniel Klader’s name on it. So it must be true, right? Right?! Well, here’s the thing about assumptions—don’t ever make them.

Truth be told, there is absolutely no record that Daniel Klader ever existed. Full stop. Say what? You read that correctly. No birth records, no death records, no service records of any kind. In the six pension records of the survivors of Van Etten’s company, not a single mention of a Daniel Klader can be found. This is quite astonishing because the individuals mention Lieutenant John Moyer, Captain William Moyer, Captain Van Etten, and even some of the members of the company taken prisoner (John Moyer among them), but no one felt it was worth mentioning a Daniel Klader.

You wouldn’t know this from reading Moore’s book, as he feels the need to elaborately detail tons of Klader family history. He lists lots and lots of information about Daniel Klader’s supposed parents and siblings, but it is hard to determine how Moore arrived at these details without birth records linking a Daniel Klader (of any sort) to any of these individuals—a fact Moore must have recognized as he has no other facts about Daniel Klader himself except his age (twenty-five) and that he was “a powerful physical specimen with a fine record of military service behind him.” He lists no evidence for how he arrived at that information.[31]

So where did this idea come from that a Capt. Daniel Klader led the detachment? I have a few theories, though it is impossible to know with any certainty. At the time of the massacre, in the company was one Pvt. Abraham Clader. At the same time, a Capt. Jacob Clader was commanding a company of militia along the frontier (and would do so for three years, under the militia law). Some of the very same men serving under Van Etten in 1780-1781 would serve under Capt. Jacob Clader between 1781 and1783, at various times, for two month tours. It seems most likely that some old timer in his advanced age combined his service under Van Etten with service under Jacob Clader, and failed to recall his first name properly.

This isn’t a stretch at all. Pension files are filled with this sort of confusion—remember, these men were into their late seventies and early eighties or older when giving their pension depositionsin 1833. Of course, no pension file exists with the name Daniel Klader (or any variant spelling), which is why I believe it was likely developed during interviews with elderly veterans during the mid-nineteenth Century.

Even while reading through existing pension files to write this article, I saw veterans of Van Etten’s company conflate Van Etten with William Moyer, even though Moyer was not at the battle (many of the men who served under Van Etten also served under William Moyer on their next tour). Uriah Tippie, one such veteran of the volunteers, mistook his service year in the seven months men as 1778 instead of 1780 and also misremembered Lt. John Fish’s first name as “Robert.”

There is no mention of a Daniel Klader until the mid-1860’s, when a newspaper, the Hazleton Sentinel, ran an article on the atrocities of the Sugarloaf Massacre written by John C. Stokes. This article, thankfully, was reprinted in 1880 and again in 1888 (the original I cannot track down). This was clearly one of Moore’s sources, as it contains all sorts of folklorist notions (like men hiding in the Nescopeck Creek to avoid being killed, or one man hiding behind a tree with his faithful dog companion whose unfortunately-timed barks led to his demise, and so forth). The article, however, also contains this interesting tidbit about a dispute among local historians:

Both Miner and Pearce say that the company was commanded by Capt. [John] Myers, while Chapman…says that Wm. Moyer was in command; but the oldest living descendants of the early settlers, with a number of whom we have conversed, agree in asserting that the company was under the command of Capt. Klader, who [performed] deeds of prodigy and valor that caused his name afterwards to inspire feelings akin to veneration.[32]

So much veneration was felt by his men, apparently, that they couldn’t even get enough courage to write about him in their pension files. Of course, after this paper was published, almost everyone decided it was the truth and so it was republished in local histories from the twentieth century onward, finally landing in Moore’s book on the massacre.

The notion that William Moyers led the company was discussed and rejected above, but the thought of John Moyer, the lieutenant of the company, is an interesting one. It seems likely that as a company officer, he could have very well been given command of the detachment while Van Etten remained in garrison with the remainder of the company (not at Fort Allen).[33] It seems likely that John Moyer was indeed left in charge—or perhaps was even in joint command with John Fish (1st Lieutenant) whose pension file also indicates that he was present at the ambush.

I have a copy of a return made on January 15, 1781, produced by Captain Van Etten at Fort Penn at end of the enlistment of the volunteers. This return is an important piece of the puzzle that was the Sugarloaf Massacre. It indicates that fourteen men were killed, despite the fact that the monument lists fifteen men (Daniel Klader doesn’t show up on the return), whereas early reports by those who buried the dead say only ten were killed. Lieutenant Moyer twice recounted that thirteen scalps were taken by the Indians (once at Fort Allen and again in his report to Samuel Rea). So what was it: ten or fourteen?

Those individuals responsible for the monument at the site clearly went by the return, because fifteen names are listed (fourteen from the return, plus Daniel Klader). But when doing research for this article, I stumbled on active duty returns from Captain Moyer’s company in November and December 1781 (over a year after the massacre) with the names of some individuals supposedly killed on September 11, 1780. So what gives?

One example is Peter Krum, whose pension deposition is presented above. Krum is listed on both Van Etten’s 1781 return and on the monument (listed as Peter Croom) has having been killed on September 11, 1780. So how could Peter Krum, who supposedly died in 1780, give a deposition in 1833 for his pension hearing? Krum also shows up as a substitute (in other words, he was hired by the county lieutenant) for another man in Captain Moyer’s company in 1781 and 1782 (spelled “Krum” or “Crum” on returns). Either Krum performed a miracle and rose from the dead, or, more likely, after the ambush he made his own way back to his farm and never returned to Fort Allen or Penn until his after tour expired (which would account for the lapse in his recollection of service after the massacre).

Krum and his family moved to Jackson County, Tennessee (where the national pension was filed), sometime after the war so he would not have had any descendants around Luzerne County in 1933 when the monument was erected. No one was there to dispute his death.[34] His was not the only name to raise red flags.

Also among the living dead is one George Shellhammer. Shellhammer is listed, like Krum, on the monument and the returns as having been killed.[35] But he also shows up on active duty returns for William Moyer’s company in 1781, and later service, in 1782, also a substitute.[36] There is only one George Shellhammer living in Northampton County in 1772 (according to tax records), and not incidentally, he was neighbors with several of his brothers-in-arms in Heidelberg Township.[37] There is also an application under his name filed with the Daughters of the American Revolution database; his death date listed: June 14, 1817.

No matter how one tries to slice it, these individuals were clearly mistakenly listed as killed. I also find it difficult to believe that John Moyer had the time to count all the scalps hanging from the belts of his captors; he likely guessed at the amount. As a result, I believe that Balliet’s original statement that ten men were killed, not fourteen, is more likely. That would also mean that there are two more names on the monument that don’t belong there. I have suspicions that one of them is Baltzer Snyder, who also shows up in later rolls, though he may have had a son with the same name. The other, alas, I haven’t been able to discern.

So how could this have happened? How is it that Van Etten didn’t notice that his own men were alive after the fighting? For one, the return was taken in January and the action happened four months earlier in September. Even by late October, Samuel Rea had not yet had sufficient knowledge of all the killed and wounded. Van Etten wasn’t at the battle either so he didn’t see which men were killed. Balliet is clear that the bodies were heavily mutilated, which leads one to suspect that it was difficult to identify the remains. Scalping distorts the face (depending upon where one begins to cut) and it isn’t like they had the ability to match dental records (CSI: Sugarloaf, anyone?). All accounts of the battle indicate that it was a chaotic rout; men were running for their lives. Several of them lost all their guns and equipment, either throwing them off to lighten their burden while retreating or having stacked them while they were eating dinner.[38] These men could have simply returned home, rather than risk their lives for the remainder of their enlistments. Or, just as likely, maybe they were on assignment at another location (as stated earlier, men from Van Etten’s command were stationed at various places along the frontier) and Van Etten just made his best guess. It could also just have easily been a paperwork error.

A lot has changed in 235 years. A once sprawling wilderness is now a suburban neighborhood nestled up against a golf course. The Little Nescopeck Creek, where the militiamen who patrolled the area stopped to rest and fill their canteens and eat their food, still runs nearby through what is now a Country Club, used as an obstacle for members who golf at the scenic site. Actually, the golf course and the encroachment of modern housing on the battlefield is a good metaphor for this particular synchronic point in history. After all, this article demonstrates how easily myth and folklore can envelope historical events to create a narrative which can be deceptively realistic; to the point where all traces of what actually happened are replaced by contemporary fiction.

Historical memory is a very powerful construct and can dominate even the most sincere attempts at “doing history.” That is why it is important for historians and students of the past alike to think critically about their sources and their subjects, to not always take them at their word—and as an added pro-tip, it is timely to do so before erecting any monuments or writing books.

[1] Rogan H. Moore, The Bloodstained Field: A History of the Sugarloaf Massacre, September 11, 1780 (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2000), 7.

[2] Moore, The Bloodstained Field, 29.

[3] “The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the six nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.” George Washington to Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, May 31, 1779; accessed June 9, 2015: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0661.

[4] Pennsylvania Archives (Harrisburg: The State Printer, 1907) Ser. 1, Vol. 7, 572. In July 1778, Northampton County Lieutenant John Wetzel wrote, “Col Strouds, informing me that he hourly expected an atack from the Indians, (their being a Large Bodey of them the numbers not yet known) at the Minesinks.” Colonel Stroud was the militia commander for the northern militia district that encompassed the region most directly at risk of enemy raids.

[5] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 7, 579: “The unexpected Incursion has given us great Concern, but as we hope there will be sufficient Vigor & Spirit in the Inhabitants to repel those Wretches, who cannot be sufficiently numerous or terrible to require more Resistance than the People can give.”

[6] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 7, 594. Sullivan wrote to Hunter: “Your letter Dated the 28th Ins’t I rece’d this Day, with the Disagreeable inteligence of the loss of Fort Freeland, your situation in Consequence must be unhappy, I feel for you, and could wish to assist you, but the good of the service will not admit of it, The Object of this Expedition is of such a nature, and its Consequences so Extensive that to turn the course of this Army would be unwise, unsafe & impolitic.” Not everyone in Sullivan’s command agreed with this decision, however. Col. Adam Hubley, also at Wyoming with Sullivan, wrote to Reed indicating that he felt that diverting some assistance to the settlements in Northampton and Northumberland would actually benefit the expedition as it would stop the war party from harassing Sullivan’s army as it moved north. Leaving them unchecked, Hubley argued, would put them in a position to cut Sullivan off from the south and leave them vulnerable. See his letter in Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 7, 596-597.

[7] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 7, 589-591; Col. Samuel Hunter, commanding Fort Augusta, wrote to General Sullivan for assistance on July 28, 1779: “Yesterday Morning, Early, there was a party of Indians & Regular Troops Atacted Fort Freeland; the Firing was heard at Boon’s place, when a party of Thirty men turned out from that under the Command of Cap’t Boon, but, before he Arrived at Fort Freeland the Garrison had Surrendered, and the British Troops and Savages was paraded Round the Prisoners, & the Fort & Houses adjacent set on fire. Cap’t Boon and his party fired briskly on ye Enemy, but was soon Surrounded by a large party of Indians; there was thirteen Killd of our People and Cap’t Boon himself among the Slain…. The Town of Northumberland was the Frontier last night, and I am afraid Sunbury will be this night…. There was about three Hundred of ye Enimy, & the one third of them was white men, as the Prisoners informs us, that made their Escape.”

[8] See my article ‘The Spartans of Long Island’, Journal of the American Revolution (November 12, 2014); accessed June 9, 2015: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/11/the-spartans-of-long-island/.

[9] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 213.

[10] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 221.

[11] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 222. In the militia’s defense, they were accustomed to receiving a double rum ration during the Philadelphia Campaign (in lieu of actual money, which apparently the state just didn’t have) and, as one might imagine, it was hard to break the habit.

[12] The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801, Vol. 10 (Philadelphia: Clarence M. Busch, 1904), 191.

[13] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 386. In all, the company would muster with eighty-three privates and a fifteen officers and NCOs. James Scooby, a sergeant upon enlisting, was advanced to 2nd Ensign on September 1. Thomas Syllaman would apparently either decline his commission as Ensign or was replaced, as Henry Bush would show up as 1st Ensign on the returns. In addition, John Moyer was made 2nd Lieutenant.

[14] So stated by Commissioner of the Bureau of Pensions in 1923, Mabel Knight; the John Van Etten Mabel was looking for was Johannes Van Etten’s son, John.

[15] Moore, The Bloodstained Field, 25-26.

[16] In a letter addressed to Governor Morris, John Van Etten distinguishes himself and his brother Johannes in actions against the Indians. See the Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 2, 720-721.

[17] Franklin established a set of unique instructions for John Van Etten’s company, including the keeping of a daily journal. His instructions, along with the organization of the company, partial muster roll, and daily rations, is at; “The Organization of John Van Etten’s Company, January 12, 1756,” accessed June 11, 2015: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-06-02-0142. Van Etten’s daily journal, or at least a few months of it, can be found in the Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 222-235.

[18] John lived in Forks Township, just a few miles from the town of Easton. Johannes, however, had a plantation in the northern part of the county.

[19] There are some early returns in 1775 that show a John Van Etten as a captain of Associators, but it is unclear if it is John, the brother (before he moved), or Johannes, or even Johannes’ son John (originality wasn’t a thing in the eighteenthcentury, apparently) who was old enough by that time and who would also be elected captain in the militia later in the war.

[20] According to an early secondary source, “The troops of Northampton county were present at the disastrous battle of Germantown, and Captain Van Etten’s company suffered severe losses.” William J. Heller, ed., History of Northampton County [Pennsylvania] and the Grand Valley of the Lehigh, Vol. 1 (New York: The American Historical Society, 1920), 136. No records exist that Van Etten fought at Germantown. Even if he had been on active duty at the time of the battle, the position of the militia on the flank of the army saw little (if any) action. The notion that they suffered heavy casualties is a fiction. It is likely that this early historian saw Van Etten’s name on the Northampton County officers’ rolls in 1777 without realizing the distinction between inactive duty rolls and permanent billet rolls indicating active service. Read more about the muster roll distinctions in my article ‘Explaining Pennsylvania’s Militia’, in Todd Andrlik, et al, eds., Journal of the American Revolution: Annual Volume 2015 (Yardley: Westholme, 2015), 212-213 (especially n.20).

[21] According to the deposition of Thomas Hewitt of Cumberland County, written August 29, 1780, “They have lived peaceably at home in the most Dangerous times,….Every Incursion the Enemy has made into this County and all the Disaffected families in this fly there for protection, whilst the well-affected are oblidged to Evacuate the County, or shut themselves up in Garrison.” From the Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 528; cf. the deposition of Henry O’Niell, Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 527-528. See also my article “Disarming the Disaffected,” Journal of the American Revolution: Annual Volume 2015, 107-120.

[22] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 156 “I will not trouble you with the distress of this County, They will no Doubt be painted to Council in lively Colours, and indeed the Picture cannot be over charged, nor should I at this Time write to you, But for a strong Belief and Persuasion, that a Body of Indians are lodged, about the head of Fishing and Muncy Creeks…. This is what we wish; Many of our Hunters who went late last Fall into that Country (which is a fine one for hunting) were so alarmed with constant Reports of Guns which they could not believe to be whitemens that they returned suddenly Back. We are not strong enough to spare men to examine this Country and Dislodge them…. This is a strange divided Quarter–Whig Tory, Yankey, Pennamite Dutch Irish and English Influence are strangely blended.”

[23] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 167. As Reed explained on April 7, 1780 to Samuel Hunter:

“It is our earnest Desire that you would encourage the young Men of the Country to go in small Parties & harass the Enemy. In former Indian Wars it was frequently done & with great Advantage….Last French War Secret Expeditions were set on foot by the Inhabitants which were more effectual than any Sort of defensive Operations. We most earnestly recommend it to you to revive that same Spirit & any Plan concerted with Secrecy & Prudence shall have our Concurrence & Support.” Unfortunately, Reed’s strategy was wrong. He failed to take into account how Loyalist opposition to the new American government would play out on the frontier. During the French and Indian War, for the most part, the majority of the backcountry supported operations into the wilderness. This was not the case in 1780. Tories were everywhere on the frontiers and they filled the ranks of Loyalist irregular units.

[24] Pension file deposition states: “And this declarant further states that in the spring of the next year, according to the best of his recollection, he volunteered as an Ensign…in a Company of Militia commanded by Captain John Vanetten a low Dutchman…He entered at Easton, Penn., & marched to Stroudsburgh—at this place the Company remained about two weeks & then marched about 8 miles distant from Stroudsburgh to a place called Fort Allen, at which place they remained three or four months, then marched to Brink’s Fort (?) about ten miles & remained there the remainder of the seven months.”

[25] Moore writes, “Colonel Stephen Hunter…ordered Captain Daniel Klader to take command of a detachment of Van Etten’s Volunteer Militia. Klader was directed to select the best of Van Etten’s Company for a dangerous mission that would take them into hostile country….” The Bloodstained Field, 35. It should be noted that Colonel Hunter’s name was Samuel, not Stephen. Moore probably got his information from the very-dated work of Henry C. Bradsby, History of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania: With Biographical Selections, Vol. 1 (Luzerne: S.B. Nelson, 1893), 200, to which is found the claim, “Col. Hunter had determined to make a demonstration against this Tory settlement, and arranged with Capt. Klader, of Northampton County, to join him in the enterprise, but the enemy had heard of the contemplated movement and proceeded to thwart it…. It is now pretty well known that this party knew that Capt. Klader intended to join Col. Hunter in the expedition up the river.” This is good fiction, but not good history. So good, in fact, that it was picked up by F.C. Johnson in The Historical Record, Vol. 6 (Wilkes-Barre: Press of the Wilke-Barre Record, 1897), 132. As happens with most fictional narratives, the story was embellished more and more; this time it included all sorts of details about how the men of the militia detachment spent their time before being ambushed—including the belief that “their guns were scattered here and there, some stacked, some leaning against stumps or logs, others lying flat on the ground” and “Some [men] were on the ground…one man was leaning against a tree with his shoes off cleaning them out, others had gone for grapes…of which party one had climbed a tree and was picking and eating the grapes from the vine.” Yes, it is quite a descriptive narrative. A shame there is no evidence to support any of it.

[26] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol 8, 560-561.

[27] The diary entry was reproduced in William L. Stone, The Poetry and History of Wyoming (Wyoming: Wiley and Putnam, 1841), 230.

[28] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 561.

[29] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 564-565.

[30] These details were reinforced by Samuel Rea on October 24 in a follow-up letter to Reed: “Col. Baliort [Balliet] informs me that he had Given Council a relation of the killed and wounded he had found Burned near Neskipeki as he was at the place of action his Accts must be as near the truth as any I could procure, tho since that Time Lieut. Myers, who was taken by the enemy in that unhappy action hath made his escape from the savages & reports that ensign Scoby and one Private was taken with him and that the party consisted of 30 Indians and one white savage, that they had 13 Scalps along with them that several of them were wounded & supposes some killed.” Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 8, 592.

[31] Moore, The Bloodstained Field, 35; no pension files name his service, no Permanent Billet Roll or Active Duty Roll lists his name, and the Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission have no militia abstract card for him—not as a private nor as an officer—despite having abstract cards for Jacob Clader and Abraham Clader. It’s all very suspicious how Moore can draw these conclusions without any evidence whatsoever.

[32] First found in the volume (no author) History of Luzerne, Lackawanna, and Wyoming Counties, PA: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Their Prominent Men and Pioneers (Lackawanna: W.W. Munsell & Company, 1880), 404; these were reprinted again in Frederick Charles Johnson, ed., The Historical Record: Vols. 2-3 (Wilkes-Barre, 1888), 125.

[33] Van Etten is never discussed as being a member of the detachment.

[34] It may seem like they might be two different people, but the pension file recalls fairly vividly his service in Northampton County, Pennsylvania, listing officers he served under (which are easily verified), including having served in Van Etten’s company in 1780. It seems like other people were called to testify to the truth of the return, and all those who did testify confirmed he lived in Northampton County—some claimed to have served with him in the militia (though not in Van Etten’s volunteers).

[35] Moore also suggests Shellhammer was killed; The Bloodstained Field, 28.

[36] For the active duty returns of Moyer’s company, April 18, 1782, see Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 5, Vol. 8, 489-492.

[37] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 3, Vol. 19, 51.

[38] A return of arms and equipment lost by the detachment can be found in Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 5, Vol. 8, 574. Given the amount of times it has been documented that the Pennsylvania militia threw away their arms to lighten their loads to run faster, it seems that this scenario was more likely.

13 Comments

One item I intentionally did not discuss, but deserves great attention, is whether Roland Montour was actually present at this battle. No primary account places him there. At best, and at the earliest, is a mention in ‘The Historical Record of Wyoming Valley’ in the late 19th Century of a “generally accepted legend concerning the post makes a very pretty story. It is said that Capt. Roland Montour, a half breed and a son of Queen Catharine of Wyoming fame, was seriously wounded in the fight.” Rogan Moore repeats this claim in his book, but the claim is ill-supported and the link drawn is quite the stretch (and the chief mentioned in the source isn’t named). So it is likely this is just another fiction added to a historic event. But again, it deserves further investigation.

I think (I’m certain) I know who your mystery Daniel Klader is. The name got misspelled often in the 17th and 18th Century until the family became more established. His name is Daniel Clutter son of Paul Clutter. The family came from Germany in 1690 and the first spelling we see in America in “Klotterin”, I’ve seen Cladder, Clader, Klatter and KLÖTTER. But Clutter is what has survived, you need to remember in those days you had Germans arriving in the great Palatine migration that could speak English so the Americans and British in New York did the best they could. Either way I assure you Daniel Clader is Daniel Clutter – Paul Clutter – Casper Clutter.

wow you were a good detective closest to the truth as i ever read

September 14. The event was recorded

i have found diary’s to be more truthful

thank you for taking the time to research this history

and you are right in wanting to have a disclaimer near the monument

thanks much steve

Thanks Steve! I thought you’d enjoy the article. Was it worth the wait? =)

yes and sorry for being impatient

can i print your research and take to the historical society ?

Absolutely.

Excellent investigatory analysis! I wonder how many other “historical accounts” can’t stand up to scrutiny afforded by modern research capabilities. Thought provoking and an important lesson to question all sources, even primary ones!

Thanks Gene!

A note of interest: read the account of Captin Stephen Harding and the Wyoming Valley Massacre. He lost two of his sons while scouting just days before the Massacre. What his Wife did for her sons is a story of the love a mother. Captin Stephen Harding story can be found in ancestor records. Search Captin Stephen Harding and the Wyoming Massacre. Stephen is my 4 th great grand father. Furthermore, The Seneca Chief unnamed is Cornplanter, Chief of the Seneca. He has a memorial in Warren County where he died at age120 on reservation.

A quick update:

Today I uncovered two other pension files of men serving in Captain Johannes Van Etten’s company and who were at the battle of Nescopeck Creek (the Sugarloaf Massacre). One is by George Shellhammer, who is on the plaque has having been killed during the battle. Above I intimated that he might have survived. Clearly he did, as the existence of his pension file makes obvious! Here is a transcription (mine) of what he said about his service in the volunteer militia:

“That afterwards he thinks in the same year he joined a scouting party, William Moyer acted as sergeant, and marched to [illegible] in Montgomery County, and marched from there to Buckhill Luzerne County, where they had an engagement with the Indians & lost twenty one men out of forty one. Baltzar Snyder, William Supple, and two brothers by the name of Rough were killed–he then returned home (or to his residence in Linton Township, Montgomery County), he further states that he had a discharge which was destroyed by the rats…”

Something to note… he misidentifies William Moyer with his son John (who was a Lieutenant, not a Sergeant). This is actually made even more clear by his brother or cousin (not sure which), Philip, whose pension file I also discovered today. He writes (again, my transcription):

“That he enlisted for seven months and served under Captain Vanatten, Lieutenant John Moyer, and Ensign Scoobie, that he marched from Weisenberg Township, aforesaid to Mahoning Valley in Northampton County and was stationed at the house of his brother Simon Shellhammer about forty miles from Easton under the command of Lieutenant Moyer to protect the inhabitants of that district of [the] County from the Indians. That after remaining there about three months he was marched with about thirty others by Lieutenant Moyer, Sergeant Kuhns, Ensign Scoobie to Nescopeck Valley in the County of Luzerne State of Pennsylvania and that they there fought the Indians. That they lost about fifteen or sixteen men, killed, wounded, or taken prisoner, that they were obliged to retreat that Lieutenant Moyer, Sergeant Kuhns and Ensign Scoobie were all taken prisoners by the Indians but Lieutenant Moyer made his escape two or three days afterwards. That he returned to his post at Simon Shellhammers house and from there he marched under Captain Vanatta towards the New York line about forty miles above [illegible], this side of the Delaware River…”

Neither George, nor his kinsman Philip, both in their early 70’s, recall a Daniel Klader. Not a single mention is given of him now in any of the 8 pension files I’ve examined from survivors. Nearly all confirm that one of the Lieutenants was in command of the detachment (likely John Moyer). The case for the existence of a Daniel Klader is shrinking towards oblivion. Also another name can be scratched off the monument plaque–George didn’t die at the battle after all!

I am so pleased to find this information. As you can see I am related to Captain Van Etten (6th. G/Grandfather) I would love to see the actual journal he left, is it kept at Penn. State ?

Thanks for your informative work. Norman R. Van Etten

I believe there were two Weaver men in this group.Does anyone know any more about them ? Am defendant of Weavers originally from Macungie.

This is pretty great bit of history, especially as this is the second version of this I’ve heard. The first was after I discovered I was a 36/37YDNA match to a descendant of George Myers, John’s younger brother. One of the first documents exchanged is testimony by George Myers on behalf of John’s widow, to help her get a pension. So my first hearing of the tale is entirely from the Moyer/Myers’s families point of view. Photocopies of his testimony are on various Ancestry trees.

Testimony as I received it by email:

Pennsylvania File #R7737, John Myers,Catharin Null(former widow)

The State of Mississippi, Leake County 1838, November Term Leake Probate

Court.

George Myers, this day appeared before me, Jackson Warner, Judge of the

Court of Probate of the County of Leake and State aforesaid. George Myers of

the County of Kemper and State aforesaid, who first being duly sworn,

desposeth and sayeth that he was born on the 10th day of August AD 1766 in

the County of Northampton and State of Pennsylvania, that he is a brother of

John Myers, the late husband of Cathrine Null, a claiment Widow, the Act of

Congress passed July 4th 1836 and an act expanctory of said Act passed March

the 3rd 1837. That he recolects that the said John Myers, late husband of

the claimant, enlisted as a volunteer in a Company raised by his father

William Myers, who commanded the Company as Captain. That said John Myers

being Lieutenant about the year AD one thousand seven hundred & eighty, to

fight against the Shawnee Indians and engaged with them in a battle at

Neskopeck Valley, then in Indian Territory within the limits of the State of

Pennsylvania about thirty miles from the residence of the said John Myers.

That the said John Myers was captured by the Indians and restrained a

prisoner, three days and nights, when he made his escape and fled to Wyoming

(this is Wyoming Valley in Pa.) from which he wrote his father William

Myers, who in the company of other individuals, went to Wyoming and braught

him home. And this appiant states he was there when he arrived and remembers

the circumstances destinctly. This appiant further states that in a short

time afterwards the said John Myers was again called off to fight against

the Shawnee Indians. In this tour, he recolects his being engaged in another

battle in which the whites gained a signal victory over their enemys, the

Indians. A short time after John Myers returned from this tour, he was

married to Catharine Gable, the present claimant. This appiant further

states the marriage took place at the residence of the father of Catharine

Gable in the County of Northampton and State of Pennsylvania in the month of

March, One Thousand Seven Hundred Eighty One. This appiant further states

that he was at the wedding or marriage and saw with his own eyes the said John

Myers & Catharine Gable, his wife, the present claimant, put to bed as man

and wife and he further states he was present also in the morning when they

arose from their nuptial couch. And this appiant further states that after

the marriage of the said John Myers and Catharine Gable the present claimant,

the said John Myers was again called off to fight the Tories on the Delaware

and other places, but does not know what battles he was engaged in. This

appiant further states that the said John Myers was engaged more or less all

the time from this period to the end of the war, when he was honorably

discharged. Upon reflection, this appiant recolects the fact of the said

John Myers in conjuction with his father going with a company to a place

called Lizard Creek in the County of Northampton in the State of

Pennsylvania, whare a considerable number of Tories had collected and

rueting them entirley, the Tories it is said made hasty strides to reach the

shores of the Novascotia, where they might remain secure from the

indignation of the free sons of liberty, and further this appiant sayeth

not, George Myers, sworn and subscribed to in open Court, before me this 6th

day of Nov.1838, Jackson Warner