Before a single British soldier set foot on New Jersey soil, Deputy Adjutant-General of the British Army in North America Stephen Kemble was concerned for his native colony. “Shudder for Jersey,” he confided in his journal on November 7, 1776, “the Army being thought to move there Shortly.”[1] Once the invasion and occupation of the state began, friend and foe alike would understand Lieutenant Colonel Kemble’s worry, as “a scene of promiscuous pillage” spread wherever the army marched.

Throughout the war for independence, British, Hessian, and Loyalist soldiers were infamous for their plundering of towns and farmsteads. But, just how much did they plunder? What kinds of items did they take? And, how much damage could the army do in a single day to a single town? To answer these questions, we look to the town of Westfield which suffered over £8,700, or $1.5 million in 2014 dollars, worth of damage and property loss in one day in the summer of 1777.[2]

The Battle of Short Hills and the Push to Westfield

As June 1777 drew to a close, so too did the seven-month-long occupation of New Jersey by Crown forces. Gen. William Howe had failed to tease Washington and the Continental army down from their perch behind the Watchung Mountains and engage it in a general action in the flat ground around the Millstone River west of New Brunswick. “Remaining longer in the Jerseys could of course answer no good End,” was how Gen. James Grant described the situation. “It was therefore thought expedient to return… to Brunswick & to proceed from thence on the more important operations of the Campaign.”[3]

Abandoning Brunswick on June 22, Howe moved east and consolidated his forces in Amboy to make a crossing over to Staten Island, where the fleet which would carry him and the army to the Chesapeake was assembling. Seeing this movement, Washington cautiously brought his army down from the hills behind Bound Brook to a post at Quibbletown. He also detached Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling, with his division composed of Pennsylvanians under Thomas Conway and William Maxwell’s Jersey brigade in advance, upon the Short Hills just to the north of the Metuchen Meeting House.

Finding this an “opportunity of giving [Washington] a little rap before we took our leaves,” General Howe divided his army into two columns, and, late in the night of June 25, pressed north from Amboy to engage Stirling and, hopefully, force Washington into the action. At about 8 o’clock in the morning on the 26th, Hessian grenadiers of the column under the command of General Cornwallis made contact with Stirling’s line at the Short Hills.[4] With the light infantry and grenadiers of the Guards in support, and under small arms and grape-shot fire, the British and German troops rushed the height and dispersed the Americans. Maxwell and Conway’s men, along with Washington and the main body of Continentals, fell back to the safety of the Watchungs.

“The Spirit of Depredation”

Without further resistance, the Crown columns continued northward, arriving at the town of Westfield in the afternoon of June 26, 1777. Located about 9 miles west of Elizabethtown, Westfield had remained outside of the reach of British foraging parties during the winter of 1777, and was spared the depredations that befell Amboy, Brunswick, Raritan Landing, Bound Brook, and other farms and properties further south and west along the Raritan River.

The army bivouacked “upon the heights of Westfield Meeting House,” forming a diamond which surrounded the town and spread over the properties of Charles Clark, David Clark, Ephraim Marsh, Moses Marsh, John Meeker, and Moses Ross. Despite marching fifteen punishing miles and fighting under a brutal summer sun, the thirteen thousand men under Howe soon succumbed to the “symptoms of a disposition for plunder” that Maj. John André had noticed spreading among the troops two weeks earlier.[5]

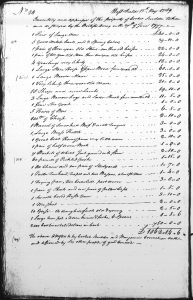

Based on inventories taken in accordance with a law passed in December 1781 to “procure an estimate of the damages sustained by the inhabitants of this state, from the waste and spoil committed by the troops in the service of the enemy and their adherents,” the troops entered at least ninety two houses in Westfield, looting and destroying a staggering list of goods.[6]

Additionally, the troops consumed at least 2,365 fence rails and posts to fuel their cook fires, with thirteen further instances of damage to “fencing stuff.” While ninety two households were plundered, only Jesse Clark, Charles Clark, and Hannah Hinds claimed damage to their homes, and a total of 1,267 pounds 18 shillings and 7 pence in cash was stolen. One enslaved person found the chance to flee from Philemon Elmer; a man with no name of unknown age worth £80, and who was listed fourth on an inventory of plundered items, after “2 excellent milk cows, 1 two year old heifer, and 2 large fat hogs.”[7]

By 9 a.m. on June 27, the army was on the move south towards Rahway, driving the hundreds of cattle they plundered and others they met on the road before them.[8] Not long after, American soldiers under Colonel Israel Shreve of the 2nd New Jersey entered the town, where he found that the British had:

made shocking havock, Distroying almost Every thing before them, the house where Gen. How stayed which was Capt. Clarks he promised Protection to If Mrs. Clark would use him well and Cook for him & his Attendance, which she Did as Chearful as she Could, Just before they went off Mr. how Rode out, when a No. of his soldiers Come in And plunder[ed] the Woman of Every thing in the house, Breaking And Destroying what they Could not take Away, they Even tore up the floor of the house, this Proves him the Scoundrel, and not the Gentleman, Gen. Lesley took his Quarters At Parson Woodruffs [and] Protected his property in Doors, the Doctor fled [but] his Wife and famaly Remained, the meetinghouse a Desent Building they made a sheep pen of threw Down the Bell, and took it of…, they Drove of[f] All the Horses, Cattle, Sheep & hogs they Could Git, – I saw many famalys who Declared they had Not one mouthful to Eat, [nor any] bed or beding Left, or [a] Stitch of Wearing Apparel to put on, only what they happened to have on, and would not afoard Crying Children a mouthfull of Bread Or Water Dureing their stay.[9]

In total, approximately eleven thousand individual items were plundered at Westfield, costing 8,702 pounds 9 shillings and 9 pence. The damages from that single day to accounted for eighteen percent of the entire damages in Essex County during the war.

The crown forces and their adherents would enter New Jersey many more times to fight, forage, and plunder. It would be another five years, and several hundred thousand pounds worth of damage later, until the war would finally leave Jersey alone.

[1] Stephen Kemble, “The Kemble Papers, Volume 1” in Collections of the New York Historical Society for the Year 1883 (New York: New York Historical Society, 1884), 98.

[2] Using the real price value for finding the relative value of the UK pound at Measuring Worth http://www.measuringworth.com/ukcompare/relativevalue.php, and the UK-US exchange rate as of May 26, 2015.

[3] James Grant to Edward Harvey, July 10, 1777 in Thomas J. McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume I: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2006), 45. On June 13, 1777, Howe moved the army from New Brunswick, where it had remained during the winter, west to Greenbrook, New Jersey, hoping to bring Washington into action, but Washington never took the bait.

[4] William Dunlap, Tice L. Miller, A History of the American Theatre from Its Origins to 1832 (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1832; reprinted Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 240. Here, Dunlap was referring to the plunder of Piscataway, Middlesex County, New Jersey, as the British swept across central New Jersey in the beginning of December 1776, but it is an apt description of what was to happen in Westfield.

[5] John Andre, Major Andre’s Journal, Operations of the British Army, June 1777 to November 1778 (Tarrytown, NY: William Abbatt, 1930; reprinted New York: The New York Times & Arno Press, 1968), 27.

[6] Peter Wilson, comp., Acts of the Council and General Assembly of the State of New-Jersey from the Establishment of the Present Government, and Declaration of Independence, to the End of the first Sitting of the Eight Session, on the 14th Day of December, 1783 (Trenton: Isaac Collins, 1784), 237.

[7] New Jersey Revolutionary War Damage Claims, Claims Against the British, Essex & Middlesex Counties, Reel 2, New Jersey State Archives. There were a total of 115 individuals who filed claims for damages in Westfield during the entire war, with 92 claiming damages for June 26-27, 1777.

[8] Andre, Major Andre’s Journal, 33.

[9] Israel Shreve to Dr. Bodo Otto, June 29, 1777, in John U. Rees, “We … wheeled to the Right to form the Line of Battle,” Colonel Israel Shreve’s Journal, 23 November 1776 to 14 August 1777, (Including Accounts of the Action at the Short Hills), http://www.scribd.com/doc/153790118/We-wheeled-to-the-Right-to-form-the-Line-of-Battle-Colonel-Israel-Shreve-s-Journal-23-November-1776-to-14-August-1777-Including-Accounts-of#scribd

5 Comments

Thanks for this article, Jason. As you and I have talked about several times, the story of a war is not just troop movements and battles won and lost. There are also a large number of other topics to consider for a fuller understanding. This article highlights the effects on the lives of civilians in the areas where troops, from either side, spent time. It also highlights the continuous nature of the war in New Jersey that affected people’s daily lives far beyond the few days of the well-known battles. Thanks again, I really enjoyed this.

Westfield must have been a very well “to do” town to have lost so much. While maybe unknowable, I wonder if the sum total of Patriot confiscations from American Loyalists exceeded the total plunder of Patriot towns by the British forces? Maybe because land was also confiscated, Loyalists lost more than the Patriots?

Here in Freehold, NJ, the British had plundered Main Street during the Battle of Monmouth. Their behavior was so extreme that even the Hessians were shocked. Speaking of which, when British troops entered Norway in 1945, they behaved badly. One of my wife’s Norwegian relatives said that by comparison, the regular German army troops who had been there since 1940 were much better behaved. (Of course, the SS and Gestapo were so bad that they earned the enteral animosity of the Norwegians.) Then again, look at the elements who were desperate enough to join the British army at the time.

I enjoyed reading this article. Very interesting. I wonder whether it is possible that at least some of the plundering suggested in the claims was actually done by the American forces. Perhaps some of the claimants were loyalists whose claims against the American army would not have yielded any success. I would appreciate your thoughts on this!

You may be interested in reading my book War in the Countryside: The Battle and Plunder of the Short Hills, NJ June 1777, published in 1977. It is now a rare book but available at local libraries. It gets into the big picture of the looting over a wide area of Essex and Middlesex Counties. There is also more information on the damage to the church, and the bell that was thrown out of the steeple and taken to NYC but later recovered. I just found a stereo view of the old Westfield Meetinghouse before it was taken down and rebuilt in 1861.After almost 50 years of additional research I am working on a new edition.