I, poor creature, worn out with scribbling, for my Bread and my Liberty, low in Spirits and weak in Health, must leave others to wear the laurels which I have sown; others, to eat the Bread which I have earned.

John Adams to Abigail Adams

June 23, 1775[1]

… flour was laid upon a flat rock and mixed with some cold water, then daubed upon a flat stone and scorched on one side….

Joseph Plumb Martin

Private Yankee Doodle[2]

When the kitchen had no roof but the sky the soup was too often thoroughly permeated with burnt leaves and dirt to be palatable. Better cooking, especially baking, became a pressing necessity.

Albigence Waldo[3]

Bread. The staff of life. The one critical staple that so many relied on, civilian, soldier, mariner, politician, minister and scholar alike, it was on the lips of all in these moments of desperation during the Revolution. It is recited repeatedly in correspondence and official documents as alarmed officials clamored for the precious substance in order to feed their populations and military leaders their army and navy, while, at the same time, voracious speculators sought to corner the wheat market to produce not only the requisite flour, but also whiskey. It was not just a few paltry loaves they demanded, but thousands of them, many, many thousands, coming straight out of ovens or shipped to them as quickly as possible in barrels, also numbering in the untold thousands.

And if good hard bread is what George Washington wanted for his hungry soldiers, then what better person to provide it than a dependable, highly regarded, German gingerbread baker from Pennsylvania? Fortunately for the rebel cause, Christopher Ludwick (1720-1801), a native of Giessen, Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany, turned out to be just the right man at the right time and place. A highly valued resident of Philadelphia, where he arrived in 1754 with his prized gingerbread molds, forms, and pans, the tall and robust Ludwick set up a thriving bakery and confectionary business and was so successful that by the time of the Revolution he owned nine houses, several rental properties, over 150 acres of land and a farm in the countryside, and a bank account of substantial worth.[4]

One of the founding members of the German Society of Philadelphia (1764), Ludwick was frequently sought out by immigrating countrymen looking for guidance in their new homeland that was heavily populated by Germans, becoming known widely as their spokesman. His ability to create the sweet gingerbread, cakes, and pastries that they and members of the city’s upper class clamored for made him very popular and afforded him ample opportunity to gain their confidence in the following decades. With war approaching, the fifty-five year old Ludwick’s reputation increased in stature as he took on new roles on the colony’s behalf, as a member of the Philadelphia Committee of Correspondence, deputy to the Provincial Convention, a drafter of proposals to the First Continental Congress, assistant in establishing defenses for the city, and procurer of gunpowder for the Continental Army.[5]

In the summer of 1776, Ludwick volunteered his services as a member of the Flying Camp in New York to perform various duties on behalf of the rebellion, refusing any pay or rations in return. Wholeheartedly devoted to the cause, he exhorted young soldiers to their duty, telling them of the deprivations of war experienced in his home country. On one occasion, when some threatened to leave camp because of inadequate rations, Ludwick went before them and fell to his knees. “Brother soldiers,” he called out, “listen for one minute to Christopher Ludwick. When we hear the cry of fire in Philadelphia, on the hill at a distance from us, we fly there with our buckets to keep it from our houses. So let us keep the great fire of the British army from our town. In a few days you shall have good bread and enough of it.”[6] He apparently fulfilled their need as promised for the men remained, earning the respect and admiration of Philadelphia’s committee of observation and correspondence who recommended him to John Adams for further service.[7] Shortly afterwards, Ludwick was indeed called upon, placing is life on the line when he agreed to infiltrate Hessian lines on Staten Island in disguise, attempting to persuade their desertions, and actually meeting with some success.[8] Those important contributions notwithstanding, the man’s admirable qualities and unquestioned devotion then allowed him greater opportunities to assist the rebellion, this time tapping into his extraordinary culinary abilities.

Early on, before the creation of a competent commissary system able to provide provisions for a growing army, the Continental Congress dictated that certain rations, comparable to those allowed by the British, be provided to soldiers on a daily basis; these directions remained in place for the duration of the war. They consisted of:

1 lb. of beef, or ¾ lb pork, or 1 lb. salt fish per day. 1 lb of bread or flour per day, 3 pints of pease or beans per week, or vegetables equivalent, at one dollar per bushel for pease or beans. 1 pint of milk per man per day, or at the rate of 1/12 of a dollar. 1 half pint of Rice, or one pint of indian meal per man per week. 1 quart of spruce beer or cyder per man per day, or nine gallons of Molasses per company of 100 men per week.[9]

However, for whatever reason, Ludwick was recommending to the Pennsylvania Council of Safety that the men receive a substantially smaller amount of flour, “one pound … per week per man.”[10] In any event, it was always much easier to prescribe such quantities than it was to supply them, leading Joseph Plumb Martin to lament, “we never received what was allowed us.”[11]

The soldiers’ frequent complaints concerning their daily ration is understandable in light of the many logistical obstacles in the way. Just procuring the many thousands of barrels of flour needed to provide them with either a pound of bread or flour each and every day was a distinct challenge. New England farmers could hardly meet the demand and merchants in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore were called upon to arrange for shipment of flour to the army as it moved from Cambridge to New York and then Pennsylvania.[12]

After the barrels had been transported by wagon out into the field and their contents distributed, soldiers devoid of ovens to make bread pooled their rations and made arrangements for those qualified bakers within their ranks to take the next step. They then went into the local community and used whatever cooking facilities were available, returning later to distribute one pound of bread for every pound of flour a soldier contributed. What they did not tell them was that for every 100 pounds of flour, some 130 one-pound loaves of bread could be produced simply because water was added. This allowed bakers to make a handsome thirty percent profit when they sold the extra loaves in the open market. For those soldiers deciding to keep their flour ration, they either transformed it into a very rough “fire cake” cooked in the coals of a nearby fire or traded it with the local country folk; many instances of straggling and plundering then ensued. There was clearly much room for improvement.

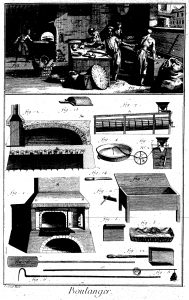

Washington had been advocating for change concerning the baking of bread and wanted temporary ovens placed within each brigade, capable of being assembled and taken apart in short order by men who knew what they were doing as the army moved about. He also ordered the fabrication of portable ovens and a New Jersey manufacturer was able to create some so small that two of them could be easily transported on a wagon. Those efforts notwithstanding, someone with industry and an understanding of the challenge was needed to oversee the entire operation. Accordingly, in 1777, as a part of its reorganization of the Office of the Commissary General, the Congress resolved on May 3:

That Christopher Ludwick be appointed superintendent of bakers, and director of baking, in the grand army of the United States; that he have the power to license … all persons employed in this business … and using his best endeavors to rectify all abuses in the article of bread.[13]

For his efforts, the new baker boss was to receive seventy-five dollars a month, and two rations each day. That same day, John Hancock wrote to Washington at Morristown telling him of Ludwick’s appointment and that “I make no doubt he will do to the entire satisfaction of the troops, and in such a manner as to save considerable sums to the public.”[14] Two days later, Washington responded in agreement and that he was happy with the news, confident in Ludwick’s ability to bring about change. “I have been long assured, that many abuses have been committed for want of some proper regulations in that department.”[15]

For the conscientious and experienced Ludwick, when told of his appointment by a congressional committee that he was expected to provide one hundred pounds of bread for every hundred pounds of flour, he refused. Instead, he told them, “No, gentlemen, I will not accept your commission upon any such terms; Christopher Ludwick does not want to get rich by the war; he has money enough.”[16] However, recognizing the error in the Congress’s understanding of how bread was made, and refusing to engage in profiteering, he consented that he would indeed take up the challenge, but with the understanding “I will furnish one hundred and thirty-five pounds of bread for every hundred pounds of flour you put into my hands.”

Wasting no time, the new “Baker General,” as he was called, immediately set out in his work and, with the aid of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, was able to obtain assistant journeyman bakers from within the state’s militia ranks. Much was expected of them and the demands arrived rapidly, with Washington writing to Ludwick on July 25 explaining the huge quantities required at that moment:

I imagine you must by this time have a considerable parcel of hard Bread baked. I am moving towards Philadelphia with the Army, and should be glad to have it sent forward. You will therefore immediately upon the Receipt of this send all that is ready down to Coryells Ferry, except about two thousand Weight which is to be sent to the place called the White House, and there wait for the division of the Army which is with me. I expect to be in that Neighbourhood the Night after tomorrow if the Weather is fair—You will continue baking as fast as you can because two other divisions will pass thro’ Pitts Town and will want Bread. You are to hire Waggons to transport the Bread, and if they cannot be easily hired, they must be pressed. I desire you will inform me at what places you have erected public Ovens that I may know where to apply for Bread when wanted.[17]

With Washington and his army marching and countermarching as quickly as it did, Ludwick had recognized the need to centralize baking operations, placing less reliance on the field ovens. Accordingly, he took over control of the Morristown public ovens and then arranged for the construction of others, personally paying for some, in Pennsylvania and along the army’s planned route of march in New Jersey. Still in need of additional men to assist in the baking and setting up and taking down of the ovens in the field, on August 4 he was forced to petition Congress for permission to hire them, and to address additional issues.

As he sought arduously to accomplish the Herculean challenge before him in finding the necessary flour, turn it into bread, and then transport it out to the soldiers, Ludwick was experiencing absurd encumbrances that seem wholly out of place. First, he was not allowed access to flour in the possession of the highly bureaucratic commissary department (itself closely scrutinized for past abuses) without specific approval from Congress, forcing him to petition for its release so he could do his job.[18] Next, he described to the legislators the “chief difficulty” he was facing at the moment, a situation that one would expect imaginative commanders on the scene to be able to deal with in feeding their own hungry men without having to bother Congress. As Ludwick explained it, “when the bread is baked he is at a loss to know in what manner he shall dispose thereof so that it may not be wasted.” Apparently nobody was willing to take control of the bread once it left the ovens in order to get it to waiting soldiers and Ludwick reasonably suggested that appropriate officers be appointed for its receipt. But that was not all, as he also sought ways to transport it, asking for “covered Waggons large and strong enough to carry a Ton,” so that the bread could be stored in a safe manner, “under a good Roof and not remain in the open fields.”

Congress agreed with Ludwick’s commonsense suggestions, allowing him one thousand dollars to build ovens and to hire additional men while also adding an interesting requirement with regard to the wagons.[19] While Ludwick did not mention security as a problem in his petition, Congress required that the wagons he requested be constructed of “tight bodies capable of being locked or fastened up.” Security was clearly an issue and now bread, of all things, was being held under lock and key.

As British designs on Philadelphia were becoming known in 1777, on September 5 Washington dashed off directions to Ludwick to leave the Morristown ovens under the supervision of someone else and to personally report to him. While he traveled, Washington further directed that he make arrangements to forward all the bread that was being made at two other locations to his camp, telling him that it “is an indispensable necessity.”[20] He further directed that Ludwick go to Philadelphia and “set as many ovens as you can procure to work in baking hard bread.” Unfortunately, the results at Brandywine and Germantown thwarted those efforts as the British moved into the rebel capital and Washington retired into winter quarters at Valley Forge.

At some point in these months, Ludwick prepared a list of ovens available at various locations to bake the army’s bread. Not all of them were in operation at that moment because of attending problems relating to needed manpower and fluctuating availability of the necessary flour. The list reveals just how industrious he was and the large scale of his operations and responsibilities: two ovens at Morris Town (baking seven hundred pounds a day); two in Pitts Town (same quantities); three in Trenton; one in Elizabeth Town; two in Valley Forge; and one at Reading.[21]

Spending the winter at Valley Forge with Washington, with whom he developed a close relationship, Ludwick’s focus was on the home of Colonel William Dewees, Jr., where he set up his main ovens while additional smaller ones were erected at various points throughout the encampment.[22] At some point, he appears to have done some private baking for his commander in chief (gingerbread, pastries?), submitting a bill to him in April 1778 for thirteen pounds ten shillings.[23] While he appears to have handled the difficult winter time assignment with aplomb, for whatever reason in February 1778 Congress decided to establish a second company of bakers with the understanding that it not interfere with Ludwick’s authority.[24] However, the experiment met with its own set of problems and was abandoned several months later.

Ludwick continued to serve the army in admirable fashion throughout the remainder of the war, despite trying to resign (an effort rejected outright by Congress) because of an inability to find replacement bakers for those leaving at the expiration of their enlistment terms and persistent logistical difficulties that seemed to never go away. After leaving Valley Forge, he and his men continued baking at Morristown (providing 1,500 loaves daily in 1780) and then at West Point where production increased to some 6,000 to 8,000 pounds a day. While his main base of operations remained there, he set up additional ovens several miles to the south at Stony Point and Verplank’s Point. Finally, in 1781 Ludwick accompanied the army to Yorktown where, upon the British capitulation, Washington ordered that he bake 6,000 pounds of bread, saying to him, “Let it be good, old gentleman, and let there be enough of it, if I should want myself.”[25]

The war was not kind to Ludwick in other regards as he found out when he returned home. His Germantown home had been thoroughly plundered by the British and he was left with little money to satisfy his immediate needs; much of it expended on the rebellion’s behalf in paying his assistant bakers and in obtaining necessary supplies when a stingy Congress failed to do so. By 1785, Ludwick was in such need that he found himself seeking the assistance of former commanders in support of a petition to Congress for relief. Writing to Washington as a last resort, he reminded him of their past times together as he explained his current difficulties:

As Your Excellency often expressed a friendship and Regard for your old Baker Master, and well know what Service he was to the Army—I now beg leave to acquaint you that, finding my private Property greatly injured and diminished by my Attention to, and Exertions in the Public Service, and by necessary Advances of my remaining Cash to some near Relations of my Wife who by the Event of the Revolution have been reduced to indigent Circumstances …. [26]

Washington did not fail him and shortly afterwards wrote directly on his behalf, telling Congress:

I have known Mr. Christr. Ludwick from an early period of the War; and have every reason to believe, as well from observation as information, that he has been a true and faithful Friend, and Servant to the public. That he has detected and exposed many impositions which were attempted to be practiced by others in the department over which he presided. That he has been the cause of much saving in many respects. And that his deportment in public life has afforded unquestionable proofs of his integrity & worth.

With respect to the particular losses of which he complains, I have no personal knowledge of them, but have often heard that he has suffered from his zeal in the cause of his Country.[27]

In the end, Ludwick did receive some remuneration (a paltry two hundred dollars), but it was never enough to fully compensate him for the many sacrifices he made during the war. Still, in the following years he managed to recoup in some measure; at the time of his death, he had sufficient resources to make various bequests, including an estate valued at $13,000 used to provide free schooling for the poor.[28]

Ludwick continued as he always had as a beloved member of the Philadelphia community, never ceasing to help those in need. When a disastrous fever struck the city in 1797, he and another baker went immediately to work and “baked, gratis, for the poor, several thousand loaves of bread.”[29] His many unselfish efforts on their behalf and that of the new nation were not forgotten. When he died in June 1801, it was appropriately, albeit briefly, noted:

Died, on the evening of the 17th inst. in the 80th year of his age, Christopher Ludwick, Baker General of the army of the United States during the Revolutionary war. His life was marked by a variety of incidents, which, if known, would prove interesting to every class of readers. In all the stations in which he acted, he was distinguished for his strong natural sense, strict probity, great benevolence, and uncommon intrepidity in asserting the cause of public and private justice.[30]

[1] Paul H. Smith, et. al., eds., Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1976-2000), 1:536-537.

[2] Joseph Plumb Martin, Private Yankee Doodle: Being a narrative of some of the adventures, dangers and sufferings of a Revolutionary soldier, George Scheer, ed. (Philadelphia: Eastern Acorn Press, 1962; reprinted 1995), 77.

[3] Charles Knowles Bolton, The Private Soldier under Washington (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902), 86-87.

[4] Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present, http://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=175.

[5] William Ward Condit, “Christopher Ludwick, The Patriotic Gingerbread Baker,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 81, no. 4 (October 1957), 372-373.

[6] Benjamin Rush, An Account of the Life and Character of Christopher Ludwick (Philadephia: Garden and Thompson, 1831), 11-12.

[7] Jonathan Bayard Smith to John Adams, August 28, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0237).

[8] Ludwick was also highly solicitous concerning the needs of captured Hessian soldiers following Washington’s success at Trenton in December 1776 and sought assistance on their behalf. Condit, “Christopher Ludwick,” 377. For additional information concerning Ludwick, see J.L. Bell’s Boston 1775 blog, http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2015/01/christopher-ludwick-and-prisoners-of-war.html and http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2015/01/the-baker-general-of-continental-army.html; and, John U. Rees, “’Give us day by day our daily bread,’ Continental Army Bread, Ovens, and Bakers,” http://www.scribd.com/doc/125174710/Give-us-day-by-day-our-daily-bread-Continental-Army-Bread-Ovens-and-Bakers.

[9] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Nov. 4, 1775 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1902), 3:322.

[10] Condit, “Christopher Ludwick,” 378.

[11] Martin, Private Yankee Doodle, 285.

[12] Erna Risch, Supplying Washington’s Army (Washington, DC: GPO, 1981), 197, passim.

[13] JCC, 7:323.

[14] John Hancock to George Washington, May 3, 1777, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0321).

[15] Washington to Hancock, May 5, 1777, John C. Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington (Washington, DC: GPO, 1931-1944), 8:16.

[16] Condit, “Christopher Ludwick,” 379.

[17] Washington to Ludwick, July 25, 1777, Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington, 8:475.

[18] Memorial of Ludwick to Continental Congress, August 4, 1777, Papers of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, NARA, Roll 50:193-194.

[19] Board of War, August 12, 1777, Reports of the Board of War and Ordnance, 1776-1781, Papers of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, NARA, Roll 157:305.

[20] Washington to Ludwick, September 5, 1777, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0152).

[21] Undated return, Letters and Papers relative to the Quartermaster’s Department, 1777-1784, Papers of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, NARA, Roll 199:449.

[22] Condit, “Christopher Ludwick,” 381.

[23] Ibid., 382.

[24] Risch, Supplying Washington’s Army, 196.

[25] Rush, An Account, 15.

[26] Ludwick to Washington, March 29, 1785, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-02-02-0327).

[27] Ibid., note 2.

[28] Condit, “Christopher Ludwick,” 389.

[29] Short History of the Yellow Fever, that broke out in the City of Philadelphia, in July, 1797 (Philadelphia: Richard Folwell, 1797), 27.

[30] Poulson’s American Daily Advisor (Philadelphia), June 19, 1801.

9 Comments

Great article on another unsung hero of the war! The oven at Stony Point was uncovered in the 1930s but, having been misidentified until very recently, was unfortunately destroyed. Very similar construction to the ones near Trenton.

Can you link to any further reading regarding the ovens found in NY and Trenton?

Any details on location of ovens at Morristown? Thanks

Mary and Kevin (I apologize for the delay in responding as your inquiry escaped me until now),

The sources I looked at did not provide a specific location for the ovens. However, Mary, for Morristown, there may be a way to find out. The Park Service’s Morristown National Historical Park website has a description of ovens, so you might want to check with them further to see about access to whatever archaeological studies they might have that are referred to in this article: https://www.nps.gov/search/?utf8=%25E2%259C%2593&affiliate=nps&sitelimit=nps.gov/morr&query=ovens

I would also suggest the same thing for anyone interested in other locations (i.e., NY or Trenton) that might be under the control of the NPS or local historical societies. Additionally, individual state SHPOs are a valuable resource, to include your state archaeologist which could very well have an online inventory of digs related to ovens.

Further, there are a couple of archaeologically-related articles with references to ovens that might provide further information (the first is a little dated, but might be of interest):

Edward S. Rutsch, Kim M. Peters, “Forty years of archaeological research at Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey,” Historical Archaeology, vol. 11(1) (Jan. 1977), 15-38.

Michael J. Gall, Richard F. Veit, and Robert W. Craig, “Rich Man, Poor Man, Pioneer, Thief: Rethinking Earthfast Architecture in New Jersey,” vol. 45(4) (Apr. 2011):39-61.

Contact me if you would like either or both of these articles forwarded to you.

Good luck.

A very interesting and well researched article about a vital subject, but little known Patriot. It is another example that many heroes do not carry guns.

Thanks Michael and Gene for your kind comments. It is stories such as Ludwick’s that really cause one to stop and think about those working in the background (quartermasters, sutlers, teamsters, cooks, farriers, saddlemakers, doctors, nurses, etc.) who made the efforts of the army and navy doable in the first place. They are the unsung heroes in so many different ways and it is heart wrenching to see how their good natures and willingness to sacrifice for the cause were taken advantage of by many in positions of power.

Thanks for a great article. Can you tell me where to find your citation (21) “Undated return, Letters and Papers relative to the Quartermaster’s Department, 1777-1784, Papers of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, NARA, Roll 199:449.”

I live near Pittstown (then Pitts Town) and while it’s known as a bakery location, and though Pittstown is quite small, the exact oven location is lost to time. Given Ludwick was specifically instructed to return correspondence with the location of his bakery (GW to Ludwick, 1777), I’m wondering if that letter from Ludwick to GW perhaps survived?

Kevin,

Thanks for the feedback and I am glad that you enjoyed the article.

The citation you refer to was found at Fold3, which I just managed to relocate and download. You can email me (gs*******@gm***.com) and I will be happy to forward it on to you.

Very interesting article. Do you know if there is documentation on the bread bakers? I am looking for information on one of the bakers- Cyrus Bustill. I believe he was in Philadelphia in 1777-1778 working for Christopher Ludwick as a free negro. Cyrus Bustill was born in 1732 in Burlington, New Jersey. the son of Samuel Bustill, a lawyer and an enslave woman owned by Samuel Bustill. Cyrus was sold to his second owned, Thomas Prior (or Pryor), who was in charge of providing flour for the port of Burlington, NJ. It is said that Prior established an apprenticeship with Ludwick to learn to bake bread.

Also, do you know if the bakers were paid by the Congress or as Ludwick was the pay master did he receive cash to pay the bakes?

If you google Cyrus Bustill it is widely recognized that Cyrus baked bread for George Washington troops in Valley Forge. I am looking for documentation to support that.

Thank you for any ideas you have