Co-authored with Don N. Hagist

An inevitable facet of warfare is prisoners. During the American Revolution, thousands of soldiers and sailors were captured by each side and the prisoners suffered in many ways. The impact of these captures extended far beyond immediate manpower concerns, compelling each side to confront unwanted, huge logistical considerations concerning their feeding, clothing, housing and guarding, as they also sought to exploit their use as human capital for bargaining purposes. For the lonely captured, they battled hunger, cold, illness and boredom, finding ways to mitigate their struggles by working, rioting and escaping.

There are as many stories as there were prisoners, but some common factors affected most of them. Some were typical of the era while others were specific to this war which had many distinctive attributes that made the handling and fate of prisoners different than what either side was accustomed to. Here’s a list of the overarching factors that the British and Americans had to grapple with in dealing with the men they captured, and those captured from them:

- Nations provided for their own men in captivity. Each government funded the clothing and feeding of its own men held in captivity by the enemy. Either by directly delivering it, providing funds to their captives to purchase it, or reimbursing the opposing government for it, food and clothing of prisoners remained the responsibility of their own government rather than the one that captured them. That was the theory, anyway, but putting it into practice presented many challenges. In their struggle to build and maintain a military infrastructure, neither the Continental Congress nor the individual state governments had established systems to provide for prisoners in British hands. British authorities did not relish the idea of sending money to their prisoners to buy food and other necessities, knowing that it would end up in the hands of their adversaries.

- Prisoners of war presented an unusual challenge for the British government. Treating rebelling subjects as bona fide prisoners of war would be an acknowledgement of American independence and its presence as a legitimate nation entitled to all attending international protocols. But, with an ultimate goal of reconciliation and keeping the American colonies within the British empire, prisoners could not reasonably be subjected to laws against treason that were punishable by death. This conundrum was never resolved until peace negotiations at the end of the war; instead, handling of prisoners was left largely to local military authorities in America.

- Prisoners of war presented an unusual challenge for the Continental Congress. With each state able to take and hold prisoners to the extent each was willing, there was initially no uniform way to set policy about captivity, parole, exchanges and other issues. While the Continental Congress prescribed general rules overseeing prisoners, it delegated much of the actual work to local committees of safety. Their authority allowed them to order the incarceration of prisoners, with further restrictions in solitary confinement, their limited freedom when allowed out on parole prescribing the distance they could travel from the local jail, the time of their departure and their curfew, and in accommodating their various personal needs, including access to money, food, clothing, medical care and religious services.

- Prisoners suffered from corrupt practices of their captors. The delivery of necessities to prisoners of war was subject to the whims of civilian sutlers selling their goods, and inn and tavern keepers providing lodging and food and drink to those on parole. Bribery was frequently required making life even more difficult for prisoners with little money. British prisoners held captive by Americans were often distributed among many towns in widely different conditions, and their hard money was highly sought after by cash-starved Americans. This subjected the prisoners to many corrupt practices by their captors. American prisoners held captive by the British were crammed into very limited spaces, and their food was often delivered by contractors who stood to profit by skimping. This also subjected the prisoners to corrupt practices by their captors.

- Prisoners of war could work to earn money. Large numbers of British and German prisoners supplemented the labor force in regions where they were held, which helped to offset manpower problems caused by men being away for the war. While some men could work within their places of captivity, most were granted paroles, either for the daylight hours or to live at their workplace. Farm laborers were in high demand in rural Connecticut, Pennsylvania and other places, and prisoners were hired out to live and work on farms. Tradesmen such as shoemakers provided valuable services, some even working in factories producing goods for the Continental Army. The relative freedom of working led to rampant desertion among British and German prisoners, some to settle in America and some to make their way to British-held regions. The labor market was different in the refugee-saturated places where American prisoners were held, but a few prisoners nonetheless managed to make and sell simple goods to earn a little precious cash.

- Prisoners of war could enlist into the opposing army. Prisoners could be released on whatever terms the captors chose. Both sides tried to tempt prisoners into gaining freedom by enlisting into their own armies. For the prisoners, it was not so much a question of loyalty but of improving their immediate living conditions. Some faithfully served their new army, but many used enlistment simply as an opportunity to escape. The Continental Congress forbid the practice of enlisting deserters and prisoners, but the prohibition was often ignored by recruiters desperate for soldiers. Some American prisoners enlisted into loyalist regiments for service in America, while others joined British regiments destined for service in the West Indies. Not only did thousands of individuals serve on both sides during the war, many switched sides more than once.

- The Americans had trouble housing prisoners. Without adequate space in jails and no other established facilities, they initially repurposed a large barracks building in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, far from the front lines. In other states, prisoners were dispersed in jails and other makeshift facilities. Later in the war, prison camps were established in Winchester, Virginia, York, Pennsylvania and other places. Supporting and guarding large numbers of prisoners was, regardless, a burden on every community.

-

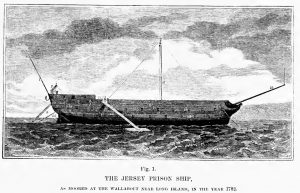

The Jersey prison ship as moored at the Wallabout near Long Island, 1782. The British had trouble housing prisoners. Far from home, the British found it difficult to house large numbers of prisoners; once war broke out, most territory firmly in British control consisted of environs close to port cities. There were no isolated, open locations to build incarceration facilities that were not dangerously close to front lines. They resorted to using abandoned buildings, most famously Livingston’s Sugar House in New York City, for army prisoners. Naval prisoners were held on board obsolete warships. There were exceptions, particularly in places like Rhode Island and Charleston, South Carolina, where captured soldiers were held on ships and captured sailors were kept on land.

- Officers were treated differently from soldiers and sailors. Common practice during this era was for captured military officers to be treated as gentlemen, not confined in jails or prisons but in houses or inns. They were afforded paroles that allowed them free movement within a few miles of the location where they were held. They had access to, and authority over, their locally-held personnel, visiting them, negotiating for their well-being, and maintaining a semblance of military discipline. They also, of course, surreptitiously abetted those plotting to escape. At the outset of the war, British authorities did not recognize American officers as being members of an established military, instead treating all captives as common enemies of government. Congress responded by threatening to treat captured British officers in the same manner, in some cases actually doing so. Throughout the war, no overarching agreement was ever reached on how officers were to be treated, leading to myriad negotiations and individual experiences.

- Some American prisoners were sent to Great Britain. Large numbers of Americans were captured at sea, primarily sailors on privateering vessels. Many of these prisoners were held not in America but in Great Britain; a few army prisoners, including the famous Ethan Allen, were sent to England as well. Prisoners were held in military prisons where they struggled with conditions similar to those faced by prisoners of both sides in America. They struggled to improve their lot by making and selling what they could, negotiating with guards and the local population, and plotting escapes. While in Europe, Benjamin Franklin worked arduously on the behalf of captive American seamen seeking humane treatment and their exchange for British captives. He instituted the practice of sea paroles allowing many hundreds of captured British sailors their freedom. The British refused to reciprocate in the release of Americans, not recognizing American privateers as being equivalent to British naval personnel.

There are many published memoirs and narratives of American, British and German prisoners of war, as well as some fine studies of the subject. For further reading, we recommend:

- Ken Miller, Dangerous Guests: Enemy Captives and Revolutionary Communities during the War for Independence (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014)

- Daniel Krebs, A Generous and Merciful Enemy: Life for German Prisoners of War during the American Revolution (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013)

- Sheldon S. Cohen, Yankee Sailors in British Gaols: Prisoners of War at Forton and Mill, 1777-1783 (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1995)

17 Comments

After the surrender of Charleston in May 1780, Cornwallis (with assistance from Balfour who clashed heatedly with Moultrie) made a list of rebel leaders who were then transferred to East Florida to remove them completely from having influence in South Carolina. The group included Moultrie himself.

Wayne,

That is interesting. I suspect that by this point in the war the British were not inclined, either politically or economically, to send rebel leaders back to England (vis-a-vis Ethan Allen) to remove their influence from the theater of operations. Prisoners were a tremendous and unwelcomed logistical drag for each side and it took a lot of imagination to deal with them in such a way that both mitigated their ability to pose a harm and assured their continued accountability. To jail or not to jail, that was the question of the day; stay tuned for more on that tomorrow.

Wayne,

Great comment. As a side note, a fact I found fascinating and perhaps requiring some more investigation is in Carl Borick’s most recent book he noted that approximately 800 men captured in the fall of Charlestown in 1780. After about a year in captivity these (mostly) Continental prisoners were recruited or forced into a newly formed British Regiment that served in the West Indies. There are some accounts of some of them coming back and seeking pensions.

American prisoners of war were regularly offered the opportunity to serve in the British forces, usually in Loyalists corps but sometimes in British army regiments as well. After the battle of Long Island in August, 1776, many American prisoners enlisted; it happened again after Brandywine. Many prisoners on the Jersey prison ship in New York harbor chose to enlist rather than stay in prison; you can read about one of them in my book “British Soldiers, American War” (Westholme, 2012). Frequently these men were put into regiments serving far away, to discourage immediate desertion. But they were never forced to serve; British law prohibited pressing men into service during most of the war, and for the period in 1778 and 1779 when it was allowed, it was only allowed in Great Britain and only under very specific circumstances.

Your book is on my list. My reference to being forced to serve comes from Borick’s book and the pension statements by those who served in the Duke of Cumberland’s regiment. By my reading there seems to have been physical force exerted on some of the prisoners. There certainly seems to have been an implied or outright threats on some occassions, join or lose your health or life on a prison ship. Of course the sources are pension statement records and need to be treated with some skepticism.

Interesting article, guys. I’m sure some of your notations will prompt quite a few readers to exclaim, “What?”

Ironic that it appears just I had begun to consider an article on Forton prison near Portsmouth, England. From my extremely preliminary research, it looks like well over 1,000 Americans ended up imprisoned there.

Mike,

It is interesting to see that the Brits’ treatment of Americans at Forton during the war did not change at all when one considers the hell they dished out to them at Dartmoor prison during the War of 1812, resulting in rioting and death in April 1815. The more things changed, the more they stayed the same.

I look forward to your take on Forton should you should pursue it.

When you pursue this piece, Mike (cuz I know you will!), be sure to consider conditions in civilian prisons for common criminals compared to those of prisoners of war. Often, studies of conditions experienced by soldiers of the American Revolution don’t compare those experiences with what could be expected in civilian life, sometimes resulting in an impression that military conditions were an anomaly or an injustice. If civilian prisons were just as bad as military prisons, that doesn’t diminish the suffering of the prisoners but it does put it into a different perspective in terms of the social norms of the era.

Don,

Good points. I can tell you from having researched the issue on the Shays period, circa 1786, that Massachusetts debtor prisons, while not as bad as Simsbury, were pretty crowded, fetid, squalid, odorous, dank, dirty and any other similar adjective you can think of. They were so concerning that civil investigations took place to inquire into exactly what was going on. In fact, in Worcester County (a hotbed during the Shay’s Rebellion), squalid prisons were what made the people riot, in addition to the jailing because of debt.

However, as you point out, it would be interesting to know what civilian prisons under colonial conditions, pre-1775, were like in that regard. Query: were they less bad and only became worse because of the war (and POWs), or were they consistently bad both pre- and post-war?

I’ve read Cohen’s book on the sailors while writing a piece for The Junto about Benjamin Franklin and American prisoners in England during the war (http://bit.ly/1QEJ4cM). It’s a highly informative book. May I also recommend: Edwin G. Burrows’ excellent “Forgotten Patriots.”

Michael,

Thank you for your suggestions. The Prelinger piece you cite from W&M Quarterly was the basis for the reference to Franklin in point 10 of the article. American prisoners in England are certainly, and sadly, an under-reported, and -appreciated, part of the war.

Mr. Shattuck and Mr. Hagist,

I am writing a paper on Washington and one of my points contains my claim on his treatment had he been captured. I have theorized that while he would not have been killed or thrown into any one of the British prisons for many reasons including rank and regard for him, he most likely would’ve been held or given parole in such a way that would give him no contact with the army and therefore no ability to lead it. Am I at least in the correct neighborhood?

This is an interesting thing to speculate on. There is precedent upon which to base suppositions: in 1776, the second-in-command of the Continental Army, General Charles Lee, was captured by the British. Treatment of Washington would most likely have been very similar to the treatment of Lee, given their similar status in the army particularly at that early stage of the war (in fact, Washington may have been treated somewhat better because Lee was considered by many to be a deserter from the British army, and was in general not as well-liked a personality as Washington).

When looking at this question, we must consider it in the perspective of the war years. Washington was no more than a high-ranking military officer at that time; his role as a statesman was still in the future, and it was not at all clear that he alone was a lynchpin upon which the fate of rebellion hung. The British certainly did try to capture him on more than one occasion, but they had no grounds to see him as having fomented the rebellion in the first place. Had he been captured, he would surely have been held but granted local parole, just like Lee was. He probably would not have been exchanged unless the Americans captured a similarly-ranked British officer. He may have been sent to Great Britain, which certainly would’ve been interesting.

And important aspect of the question is, what would have become of Washington as a prisoner had the British won the war? It’s hard to image that he would’ve been simply released in the same manner as common soldier prisoners.

I seem to recall reading somewhere in the past that there was a discussion among the British command regarding the assassination of, if not Washington, then some other high ranking officer, but that the idea was subsequently quashed by Clinton for fear that the same thing would happen to him.

Thomas,

Thank you for your interesting question and one that certainly brings to mind a multitude of issues beyond what would take place in the simple case of an ordinary soldier being taken a prisoner of war.

One thing that has become clear in my researches of the impact of the law on the behavior of officers, both British and American, is that this was a time of great change. Emer de Vattel wrote his highly acclaimed Law of Nations in 1758 and it was deemed of such importance that it was not unusual for commanders on both sides to have a copy with them in their traveling libraries. It really is an eye opening piece of work and I commend it to you for further review: http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2246

If you will enter a search term “prisoners of war” you will find numerous dos and don’t in their treatment and I think you will be able to figure out at least the bare minimum of treatment that Washington would receive had he been captured. There are also the issues of quid pro quo in play, meaning that “if you hurt my soldier, I will hurt yours the same” (see my article on this exchange between Washington and Gage: https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/05/major-christopher-french-prisoner-of-war/) as well as the international diplomatic impact that such a capture would present.

A person of Washington’s reputation and importance would certainly not have been jailed or physically harmed. At the same time, I agree with your assessment that there was a legitimate concern that he be rendered unable to provide aid to the American cause and would be closely monitored even if allowed parole. The British would have to always be aware that even in captivity, Washington would be a rallying point and constitute an important propaganda tool in the event of any future negotiations between the adversaries.

Take a look at de Vattel and I think other issues will come to mind to assist in answering your interesting question. Thank you again.

I think a notable parallel might involve the political and military leaders captured at Charleston in 1780. They were not put in prison or close confinement but were pretty much free about town. But, the British quickly tired of their influence and most of the captured leaders were taken to St. Augustine where they sat out the rest of the war.

Last year I worked a couple of weeks on Thomas Burke before getting deflected onto David Fanning. As captive Burke wanted above all to be treated like a prisoner of war instead of a prisoner of state, as he says in his January 19, 1782 letter to Greene. Were other prominent Whigs treated as “prisoners of state” or was this a special way of controlling Burke? Stewart E. Dunaway in THE BATTLE AT LINDLEY’S MILL quotes James Craig’s letter describing Burke as “by far the man of the greatest abilities and one of the most violent in the Province.” My impression was that Burke as governor was hapless before and after his capture. Maybe that’s wrong. And maybe there is testimony to his bravely resisting capture other than his own words? In the Continental Congress Burke had wielded power (the father of state’s rights!) by his obdurate punctiliousness but in elaborately justifying his violation of parole the same trait became his damning weakness, I thought. Did he find time to do anything else besides justifying himself? Anyway, I would like to hear about other Whigs treated as “prisoners of state.”