Historians have long praised newspapers for the role they played during the American Revolution, but they don’t always zero in on specific papers that were particularly important during this time. Rather, they give deserving praise to all of the press for the help they gave in winning independence. But there are particular newspapers that should be recognized for their individual contributions to American success in the Revolution. Many of them were published in major cities (particularly ports) which meant they had much more access to news from Britain than newspapers in more isolated areas.

Boston Gazette

Leading the list would obviously be the Boston Gazette. Published by Benjamin Edes and John Gill from 1755 to 1775 and then by Edes alone after that, the Boston Gazette was a major source of information about a number of important events leading up to the split from Great Britain. Much of this was because Boston was the center of much of the early conflict between the colonies and Great Britain. Many of the original reports about the arguments over taxes, the Boston Massacre, and the Boston Tea Party first appeared in the Boston Gazette. But the newspaper’s impact went beyond the content of their stories and reflected a growing opposition to the actions of British officials. The Boston Gazette became the primary mouthpiece for Samuel Adams and others who increasingly opposed the British government. Because of this reality, many of the pieces published in the Boston Gazette did more than just tell the story – they presented reports of events in the context of British efforts to deny Americans their rights. The spread of this outlook was essential if the colonies were going to break away from Great Britain and the Boston Gazette played an essential role in the dissemination of the growing attitude of opposition to the Royal Government.

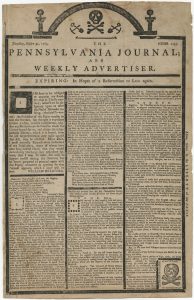

Pennsylvania Journal

The Pennsylvania Journal was published by William and Thomas Bradford in Philadelphia throughout the Revolution except for the period when the British occupied the city. Much of the news about the actions of the Continental Congress appeared in the pages of this newspaper and then were reprinted throughout the country. The Journal became known for its opposition to the actions of the British government pretty early. Probably the most famous early example of this opposition came on October 31, 1765 when the Journal’s masthead was redesigned to look like a tombstone to emphasize that British actions were destroying American rights. For years, the Journal was given credit as the original source for Thomas Paine’s famous series of letters called the American Crisis Papers. Although not an accurate statement, this has served to increase the historical reputation of the Journal through the years.

The Pennsylvania Journal was published by William and Thomas Bradford in Philadelphia throughout the Revolution except for the period when the British occupied the city. Much of the news about the actions of the Continental Congress appeared in the pages of this newspaper and then were reprinted throughout the country. The Journal became known for its opposition to the actions of the British government pretty early. Probably the most famous early example of this opposition came on October 31, 1765 when the Journal’s masthead was redesigned to look like a tombstone to emphasize that British actions were destroying American rights. For years, the Journal was given credit as the original source for Thomas Paine’s famous series of letters called the American Crisis Papers. Although not an accurate statement, this has served to increase the historical reputation of the Journal through the years.

Massachusetts Spy

The Massachusetts Spy, originally produced in Boston, moved to Worcester in early 1775. Published by Isaiah Thomas, the Spy supplemented the materials produced by the Boston Gazette about events in Massachusetts during the years leading up to the Revolution and throughout the war. Probably the most famous piece first carried in the Spy was Thomas’s report on the Battle of Lexington. Many reports about this first battle in the Revolution blamed the British for starting the fighting, but Thomas’s account became the most famous and was the one most remembered: “Americans! forever bear in mind the BATTLE of LEXINGTON! where British Troops, unmolested and unprovoked wantonly, and in a most inhuman manner fired upon and killed a number of our countrymen, then robbed them of their provisions, ransacked, plundered and burnt their houses! nor could the tears of defenseless women, some of whom were in the pains of childbirth, the cries of helpless babes, nor the prayers of old age, confined to beds of sickness, appease their thirst for blood! – or divert them from the DESIGN of MURDER and ROBBERY!” Thomas went on to print much more about the Revolution, but this one piece was reprinted almost everywhere and made his newspaper very well known.

Pennsylvania Evening Post

The Pennsylvania Evening Post appeared in Philadelphia from 1775 to 1782. Published by Benjamin Towne, the Evening Post produced its only major contribution to the Revolutionary effort on July 6, 1776, when it contained the recently adopted Declaration of Independence. Other newspapers all over the country followed this effort and published the Declaration for all to see. The paper also sometimes contained pieces based on information acquired from members of the Continental Congress. The Evening Post also proved to be an unusual paper during the Revolutionary era because it continued to be published throughout the war, whether Philadelphia was under the control of the Americans or the British. That did not happen elsewhere because printers fled in the face of the opposing side’s army. But Towne was able to continue publishing his paper because he figured out how to get along with the people in charge and was not molested for “switching sides.”

Connecticut Courant

The Connecticut Courant was published in Hartford. It had several printers during the Revolution: Ebenezer Watson from 1769 to 1777, then his widow and George Goodwin from 1777 to 1779, and finally Barzillai Hudson and George Goodwin from 1779 until after the war ended (the paper is still published today as the Hartford Courant). The importance of the Courant grew out of the fact that it continued to publish as other major cities nearby were occupied by the British. While Boston, New York, and Newport were occupied by the British, the Courant became a major source of information for many Americans. The circulation of the paper greatly increased throughout the states from New York northward because it was the only major newspaper continually published at this time.

New York Journal

The New York Journal began in New York City, but it moved around the state to several different places in order to ensure that publication could continue without interference from the British Army. Printed by John Holt from 1776 to 1784, the Journal contained many pieces written by strong advocates of independence. Holt was determined to continue the publication of his newspaper and fled from British forces when necessary. Because of his willingness to move, the Journal provided much information to people in New York about the Revolution and what was happening throughout the country. The Journal also became a source for newspapers throughout the country as well because of its location close to the fighting in Massachusetts and New York. Essays and news stories on all sorts of topics appeared regularly, but the most important pieces published in the Journal were probably the “Journal of Occurrences” that reported events in Boston from 1768 to 1769.

Providence Gazette

The Providence Gazette was probably the most important and influential newspaper published in Rhode Island in the 18th century. Founded by William Goddard in 1762, the paper was produced by both William and Sarah Goddard up to 1769. In 1767, John Carter joined the paper and he gained ownership in 1768. Throughout the Revolutionary era, the Gazette took a strong stand in favor of the rights of the colonies and strongly supported independence once it was declared. In fact, Carter had urged the colonies to unite in the face of British tyranny on several occasions before independence was declared. He stated that history was being made and Americans should participate in it fully. The location of the Gazette in Providence meant that it was close to the conflicts that occurred in Boston and New York, so the Gazette became an important source of news about events in these places when the local newspapers there were no longer functioning.

Rivington’s New York Gazetteer

Rivington’s New York Gazetteer, or The Connecticut, New-Jersey, Hudson’s River, and Quebec Weekly Advertiser began publication in New York City in 1773 and continued off and on (and under various titles) until 1783. The Gazetteer was published by one of the best printers in America at that time, James Rivington. The Gazetteer was a strong supporter of the British Government throughout the conflict and Rivington became the Royal Printer of New York and continued his newspaper as the Royal Gazette once war broke out. Throughout the years of its publication, the Gazetteer contained the most foreign news of any newspaper produced in America. As a result, newspapers all over the country reprinted materials from the Gazetteer and thus this Loyalist newspaper became a major source of information for everyone (whether they supported the paper’s political stance or not). Today it is probably the number one source of information about the stance of the Loyalists because of where and when it was published.

New Hampshire Gazette

The New Hampshire Gazette was published in Portsmouth by Daniel Fowle from 1756 to 1776 and from approximately 1778 to 1785. In the years between 1776 and 1778 Benjamin Dearborn printed the paper. The Gazette never took a strong political stand against the British government under either printer, but the overall general tone favored the colonies and their efforts to control their future. The strongest statement made by the Gazette about the arguments with Great Britain probably came when Dearborn changed the title of the publication to The Freeman’s Journal, or New-Hampshire Gazette. The title was changed in May 1776 and seems to have been influenced by the growing calls for independence. Because New Hampshire was never the center of the fighting during the Revolution, Fowle and Dearborn was able to provide regular continuous news of events in the war to their readers and other printers across the country who would reprint extracts of what the Gazette carried.

South Carolina Gazette

The South Carolina Gazette was published in Charleston by various members of the Timothy family. Founded in 1734, the paper continued until 1800. From the beginning of the growing arguments with Great Britain, the Gazette supported the American side. Publication was interrupted from time to time because of issues related to the conflict with Great Britain, but the need for information helped revive it whenever this happened. The Gazette always had a group of advertisers which made it possible to handle financial and production problems whenever they arose. Being published in Charleston enabled the Gazette’s producers to include much about the activities of the British army prior to the fall of Charleston in 1780. The Gazette thus served as the primary source of information for the South throughout this era and printed much information that was reprinted throughout the country.

19 Comments

Sue,

Just out of curiosity, is there any particular reason why the Virginia Gazette(s) did not make the list?

Norm

Too bad America’s newspapers have spent the last 200 years abandoning a responsible role.

While I agree with you on the current state of journalism, 18th century newspapers were not above a little muckraking, a little trolling, and a little partisan hackery all mixed together!

It would be quite a stretch to suggest that newspapers of the Revolutionary War era, in general, were more “responsible” than today’s newspapers in general.

While Todd Andrlik’s landmark study “Reporting the Revolutionary War” has shown that newspapers of the era were a generally reliable news source, they were every bit as politically polarized as newspapers are today – arguably even more so. Editorial content was vigorous in attacking “opposition” and aggrandizing “supporters”, and many newspapers did not hesitate to publish rumors, blatant propaganda, outlandish satire and viscous personal attacks, often pseudonymously.

Newspapers of the Revolutionary War era are fantastic resources for historical research of all sorts, but, just like today, the reader must be very cautious about believing what’s written in the newspapers.

Don beat me to it and is 100% right. Media bickering, bias, partiality and propaganda were perfected during the American Revolution with Patriot and Loyalist newspapers fighting to keep their respective populations engaged. Eighteenth-century newspapers often touted their impartiality in their mastheads (nameplates), but the printer’s point of view was frequently apparent by the rumors, distortions and exaggerations s/he published. Still, colonists were well aware of any bias much like modern consumers of left- or right-leaning 21st century media.

Another important note is that bias isn’t synonymous with inaccuracy. Sure Revolution-era newspapers utilized an impressive menu of propaganda tactics (name calling, fear mongering, selective news printing, demonizing the enemy), but colonial newspaper printers still understood the importance of credibility (and its relation to revenue) and worked hard to corroborate the oral, manuscript and printed intelligence coming through the print shop, particularly after major battles.

There were 2 reasons for not including the Virginia Gazette(s). First, it is difficult to figure out which one to talk about. Second, and more importantly, I focused primarily on newspapers who either published important stories or helped spread these stories around. When considering the list from these aspects, I believe that the papers I listed played a more influential role than the Virginia Gazette(s). That’s not to say they weren’t important — they just came in between 11 and 15 on my list.

Just to elaborate on what Carol wrote, for those not familiar with the Virginia Gazette:

The colony of Virginia had some sort of law requiring that any newspaper published in the colony be called The Virginia Gazette (that’s probably an oversimplification, but will suffice for now). The result of this was that, in the 1770s and 1780s, there were several newspapers in print simultaneously by different publishers, all with the same name. The only way to distinguish them is (and was) by the publisher – so we hear of Purdie’s Virginia Gazette, Dixon & Hunter’s Virginia Gazette, etc. To further confuse matters, sometimes a given paper was taken over by a different publisher, so the publisher name might change even though in terms of publication continuity it is effectively the same newspaper.

As a whole, The Virginia Gazette family of newspapers was influential in its day and is a valuable resource today, but, as Carol says, it is difficult to single out any single publisher’s Virginia Gazette as being more influential than another. And, of course, the definition of “influential” depends a lot on what sort of influence you have in mind.

Colonial Williamsburg offers an impressive (and free) digital archive of 18th century Virginia Gazettes (1736-1780). You can access the papers via this link.

One noteworthy Virginia Gazette is the August 26, 1775 issue published by Dixon and Hunter. It is featured in my Reporting the Revolutionary War book. Don N. Hagist describes its uniqueness within his essay on Bunker Hill:

Here is a link to a high resolution image for anyone interested in seeing it.

Thanks Todd for the link and information on the Virginia Gazette. Are there any other digital archives for these Revolutionary era newspapers?

In addition to those mentioned by Todd below, another subscription digital collection is the Pennsylvania Gazette, at

http://www.accessible-archives.com/collections/the-pennsylvania-gazette/

And some South Carolina newspapers (link).

The Massachusetts Historical Society’s “Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr, Jr.” Free access to a nice collection of Bay State papers at http://www.masshist.org/dorr/

Todd – in the example (August 27, 1775) you shared take note of the handwritten name in the upper left corner – St. George Tucker. He of Williamsburg, VA (and Bermuda powder plot, among much else) fame. His house is preserved in Williamsburg.

In addition to the Virginia Gazettes, there are a handful of digital archives with extensive collections of Revolution-era newspapers, but they typically require a paid subscription or access via an academic library:

**Early American Newspapers (http://www.readex.com/) – AT RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS

**British Newspaper Archive (http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/) – PAID

**London Gazette (https://www.thegazette.co.uk) – FREE

On a much smaller scale, but free, I created a mini archive of full newspaper issues featured in Reporting the Revolutionary War. You can find those issues by clicking here and navigating through the chapters.

Todd and Don, thanks for the links for the digital newspapers!

I liked the Top 10 Printers article. I like Samuel Loudon Printer at Fishkill NY during the war.

Loudon and Holt were both in New York and left for the same reason. Loudon eventually set up

his shop at Fishkill, N.Y., in a private house. From there he printed currency for New York, one

of the state’s constitution and some for General Washington.

Loudon’s shop was near a supply depot at Fishkill for the American Army. The supply depot

is a historical site today. (FishkillsupplyDepot.Org)

Do you have any information on a printer F. Green? I have a colonial note printed in Annapolis MD August 14 1776. Can you help? I volunteer at the SWFL Military Museum and Library in Cape Coral, Florida. Thank you for any information you can provide.

A Frederick Green is listed in an on-line source for period printers which can be found at

github.com/AmerAntiquarian/Printers-File

The best current book on Revolutionary Era Printers is Revolutionary Networks by Joseph Adelman which was reviewed in JAR last fall. I recommend this book for information on the extended Green family and their publishing businesses.

https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/10/revolutionary-networks-the-business-and-politics-of-printing-the-news-1763-1789/

This was Frederick Green, son of Anne Catherine (Hoof) Green, one of America’s first women printers. If you research her, you’ll find some information about Frederick, who carried on the family business in Annapolis.