Joseph Paugenit, Jonas Obscow, Anthony Jeremiah, Simon Peney, Obadiah Wicket, and Alexander Quapish. These are not household names to the average history enthusiast. But they are among the two hundred Indians from eastern Massachusetts who fought in the Revolutionary War. Few people are aware of the contributions that these and another thousand or more Native soldiers—Catawba, Lumbee, Mohegan, Oneida, Penobscot, and Stockbridge and others—made to the American cause during the Revolutionary War.[1] Similarly, few people are aware of the circumstances that led Indians to wartime military service.

For the 1,700 remaining Indians in eastern Massachusetts, much had changed in the 150 years since the Pilgrims arrived. Life was characterized by poverty and land loss. Many Indians lived on small reservations or in isolated enclaves, subjected to the whims of inept state-appointed agents called “guardians.” Disease, despair, and alcohol abuse led to low life expectancies. Women peddled baskets and worked as housekeepers or herbalists. Men carved out a niche as warriors in colonial militias. Others were wanderers—traveling farmhands and laborers. Still others labored as whalers on long journeys from southern New England ports. Intermarriage was common. Some now lived in small cabins. Many had adopted Christianity. But traditions remained strong and kinship networks were still intact.[2]

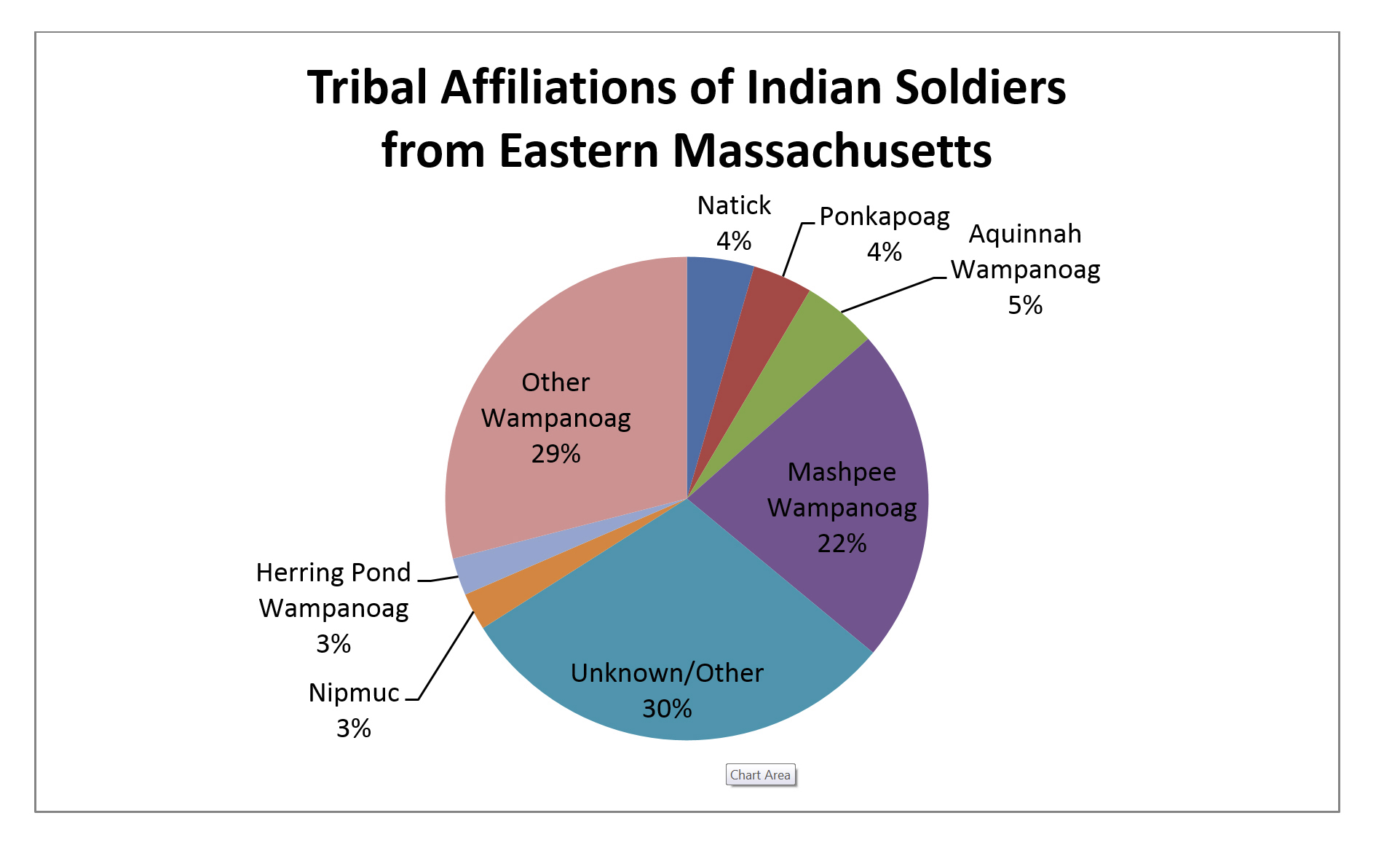

| Tribal Affiliation or Community | Percentage of Total | Approximate Number |

| Natick[3] | 4.5 | 9 |

| Ponkapoag | 4 | 8 |

| Aquinnah Wampanoag | 5 | 11 |

| Mashpee Wampanoag | 22.5 | 46 |

| Unknown/Other | 30 | 60 |

| Nipmuc | 2.5 | 5 |

| Herring Pond Wampanoag | 2.5 | 5 |

| Other Wampanoag | 29 | 59 |

| Total | 100 | 203 |

In 1775, Massachusetts Indians had numerous reasons for enlisting. Many wished to carry on a family tradition of military service. Most Massachusetts Indians fought for the American cause out of economic necessity. Others had no choice; as servants they were forced to fight in the military by their masters. Just as their reasons for enlisting varied, their wartime experiences were equally unique. Some of eastern Massachusetts Indians proved to be brave and bold soldiers, while others fell short of this distinction.

The following profiles reveal the representative experiences of six Indian Patriots during the Revolutionary War.

1 // The Warrior Tradition: Joseph Paugenit, Jr.

Many Indians fought to fulfill family tradition, or because that’s what Indians did. Indians from the Christian communities of Natick and Ponkapoag (present-day Canton) in particular, had a long tradition of military service to Massachusetts. In 1756, Joseph Paugenit and his wife Zipporah, two Natick Indians, requested disability assistance from the Massachusetts legislature. Joseph sustained serious wounds while serving in a provincial regiment during the French and Indian War. Because he could no longer work, he and Zipporah sank into poverty. Yet five days after the first shots were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, Joseph’s son, Joseph, Jr., joined the American cause.[4] Despite the dangers and risks, Joseph Paugenit, Jr. was carrying on his family’s warrior tradition. The young Paugenit signed up for three years of service.

Paugenit, Jr., whose name derived from an Indian word for “codfish,” was one of sixteen Indians who fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775. Four others came from Massachusetts. Paugenit would later fight at Harlem Heights in 1776 and at one or both of the Battles of Saratoga in 1777. He died in a military hospital in near Albany in 1777, either due to fatal injuries or smallpox. He was only 23 years old.[5]

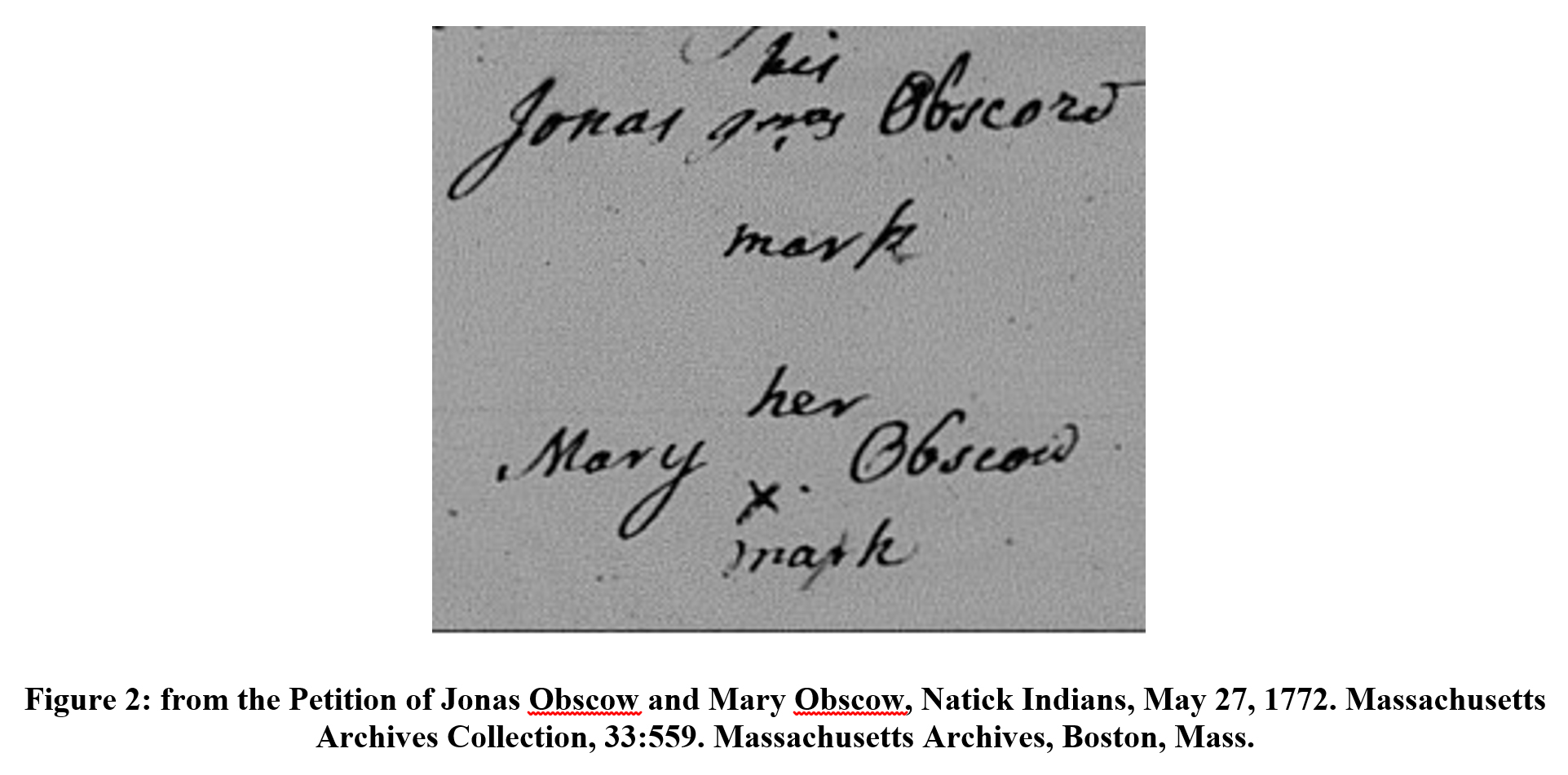

2 // The Debtor: Jonas Obscow

Many Massachusetts Indians saw combat because they were poor and had no other options. On May 27, 1772, Jonas and Mary Obscow petitioned the Massachusetts Council. Sickness had afflicted the family for several years. “Several of their children have died,” the petition stated, and they “have become justly indebted to physicians and others.” The two Natick Indians, perhaps under duress from their state-appointed agents, sought to sell what many Indians held most dear—a tract of land. The Massachusetts Council granted the Obscows’ petition and thirty-seven more acres fell out of Indian hands. This was a familiar tale for Massachusetts Indians at the time.[6]

Eastern Massachusetts Indians like Obscow were quick to join the military to escape poverty and woe. Obscow left his wife and seven-year-old child and joined a militia company in May 1775. He saw action in Cambridge. Like so many Eastern Massachusetts Indians, the lure of enlistment bounties and clothing soon drew him to the Continental Army. Indian enlistees in the Continental Army could choose between a “bounty coat” or its cash equivalent. Obscow opted for the coat on November 21, 1775. Indians were seldom treated as equals in civilian white society. But military service offered impoverished minorities equal enlistment bounties, equal pay, and camaraderie. Obscow’s exact fate remains unclear; he apparently saw action in Rhode Island in 1778, but he never returned home.[7]

3 // The Seafaring Indian: Anthony Jeremiah

One of the several niches that eastern Massachusetts Indians had carved out for themselves in the eighteenth century was working as sailors on merchant vessels or as whalers. It is no surprise that some Indians saw service on the seas; they already possessed the requisite nautical experience. Anthony Jeremiah, a Nantucket Indian, was one of these men.

Jeremiah fought bravely in the Continental Navy. Affectionately known aboard as “Red Jerry,” or “Red Cherry,” he served as a gunner under Captain John Paul Jones on the Alfred, the Ranger, and the Bon Homme Richard. In September, 1779, Jeremiah survived the battle off the English coast between the Bon Homme Richard and the Serapis. Then, with tomahawk in hand, Jeremiah joined the boarding party that overtook the Serapis and compelled its surrender.[8] It was a shining moment for both Jeremiah and the American cause.

After the Revolutionary War, Indians in eastern Massachusetts would continue to travel in search of work. Some went back to sea as sailors on merchant ships or as whalers. This work again meant extended absences from reservation lands which were becoming fewer and smaller. Men like Jeremiah found a home on the high seas until the collapse of the whaling industry in the mid-nineteenth century.

4 // The Lousy Soldier: Simon Peney, and the Deserter: Abel Suppawson

A few Indians, like portions of the non-Indian population, proved to be poor soldiers. On March 20, 1781, Simon Peney, a Mashpee Indian, was sentenced to receive 80 lashes “on charge of stealing cider.” The sentence was soon dropped. But on May 13 that same year, Peney was sentenced to receive 50 lashes “on charge of repeated absence from roll-call without leave.” Peney was listed as deceased in August, and then, inexplicably, sick one month later.[9]

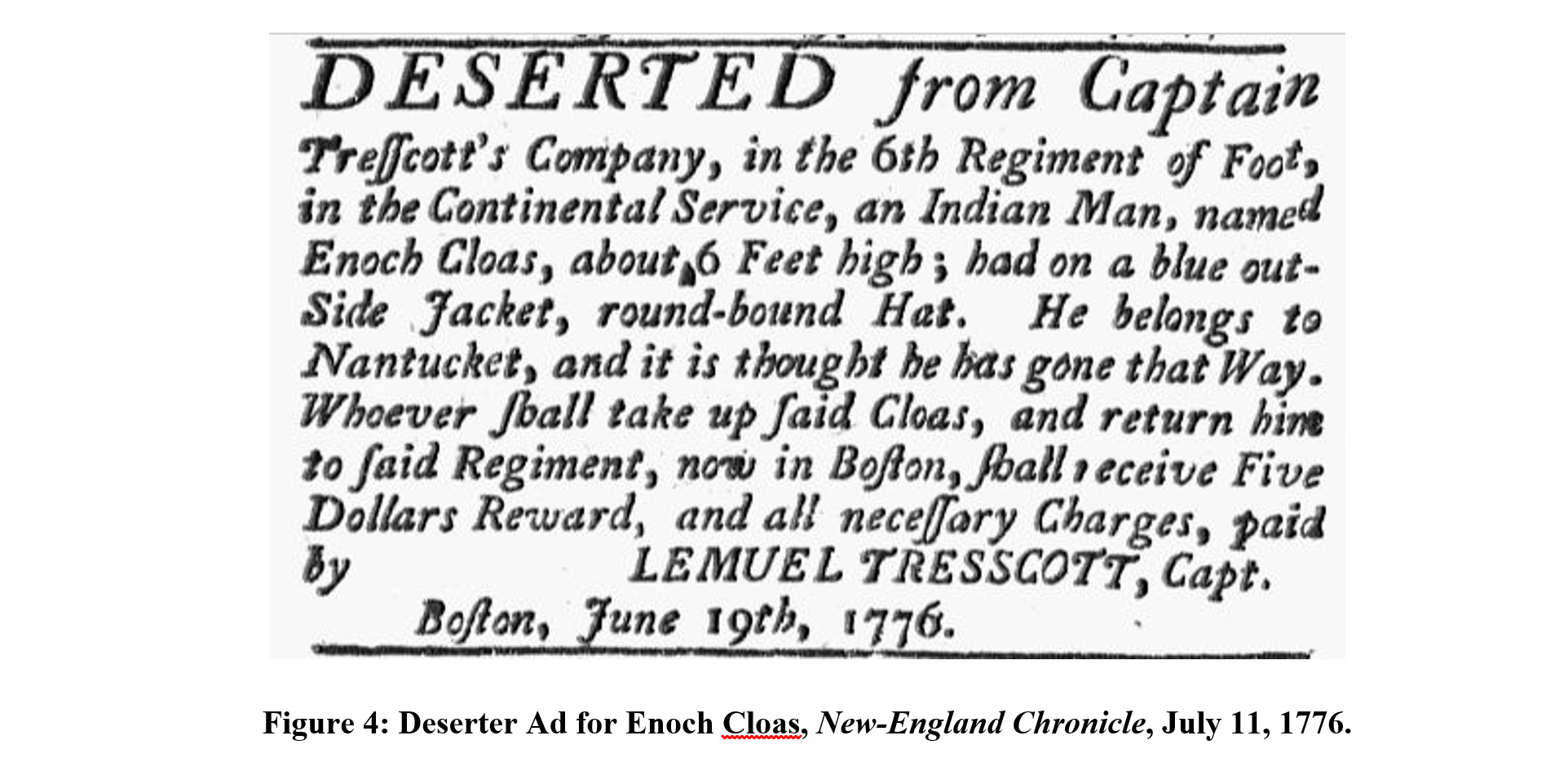

A search of ads in war-era newspapers reveals that, like non-Indians, Indians also deserted their units and returned home. Enoch Cloas of Nantucket apparently eluded capture.

But Abel Suppawson of Cape Cod was less lucky. In 1778, Suppawson, a veteran of the Battle of Bennington and the Battles of Saratoga, deserted his company in the 14th Massachusetts Regiment. Yet, consistent with the equal treatment Indians received in the army, officers afforded Indian offenders with leniency. Suppawson was spared a harsh punishment, and was returned to action. Nonetheless he died later that year.[10] Soldiers from all racial groups included some unreliable soldiers. Indians were no exception.

5 // The Pensioners: Isaac Wickhams and Obadiah Wicket

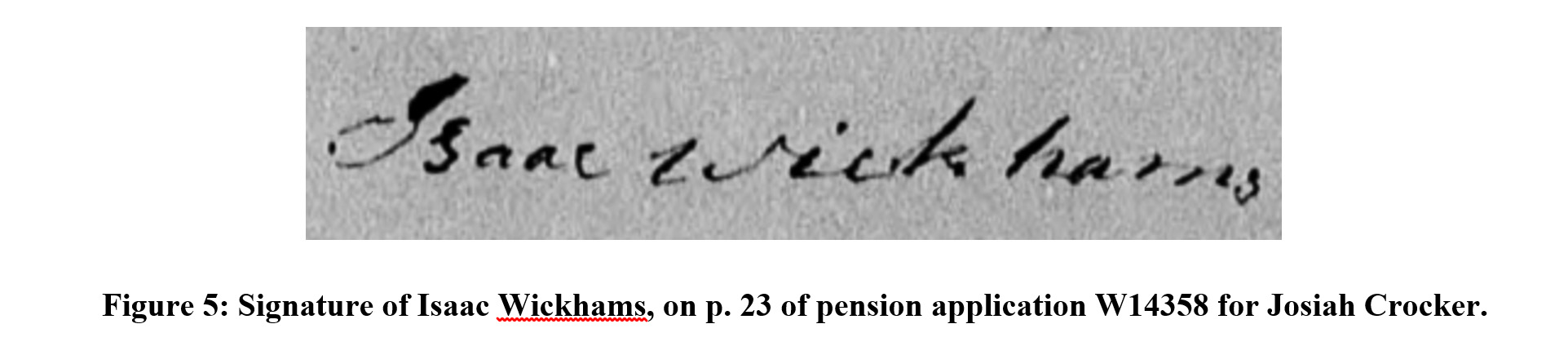

Only two of the Massachusetts Indians that served in the Revolutionary War received federal pensions. Transience, low life expectancy, and the difficulty of gathering supporting testimony of whites—decades after the war had ended—contributed to this underwhelming number. Mashpee Wampanoag Isaac Wickhams served from 1780 to 1783. He had served in one of the light infantry companies under Lafayette and witnessed Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown. When he applied for a pension in 1818, Wickhams was suffering from “chronic lameness” and was eking out a humble subsistence in an “old house 10 by 14 feet one story.” He purchased a cow with his first pension payment. In later years, Wickhams testified on behalf of other pension applicants and their widows. In time, he became the oldest living Mashpee veteran.[11]

That same year, 1818, Wickhams was also conned into signing a fraudulent petition contrary to the best interests of Indians on the plantation.[12] So much for veterans’ benefits!

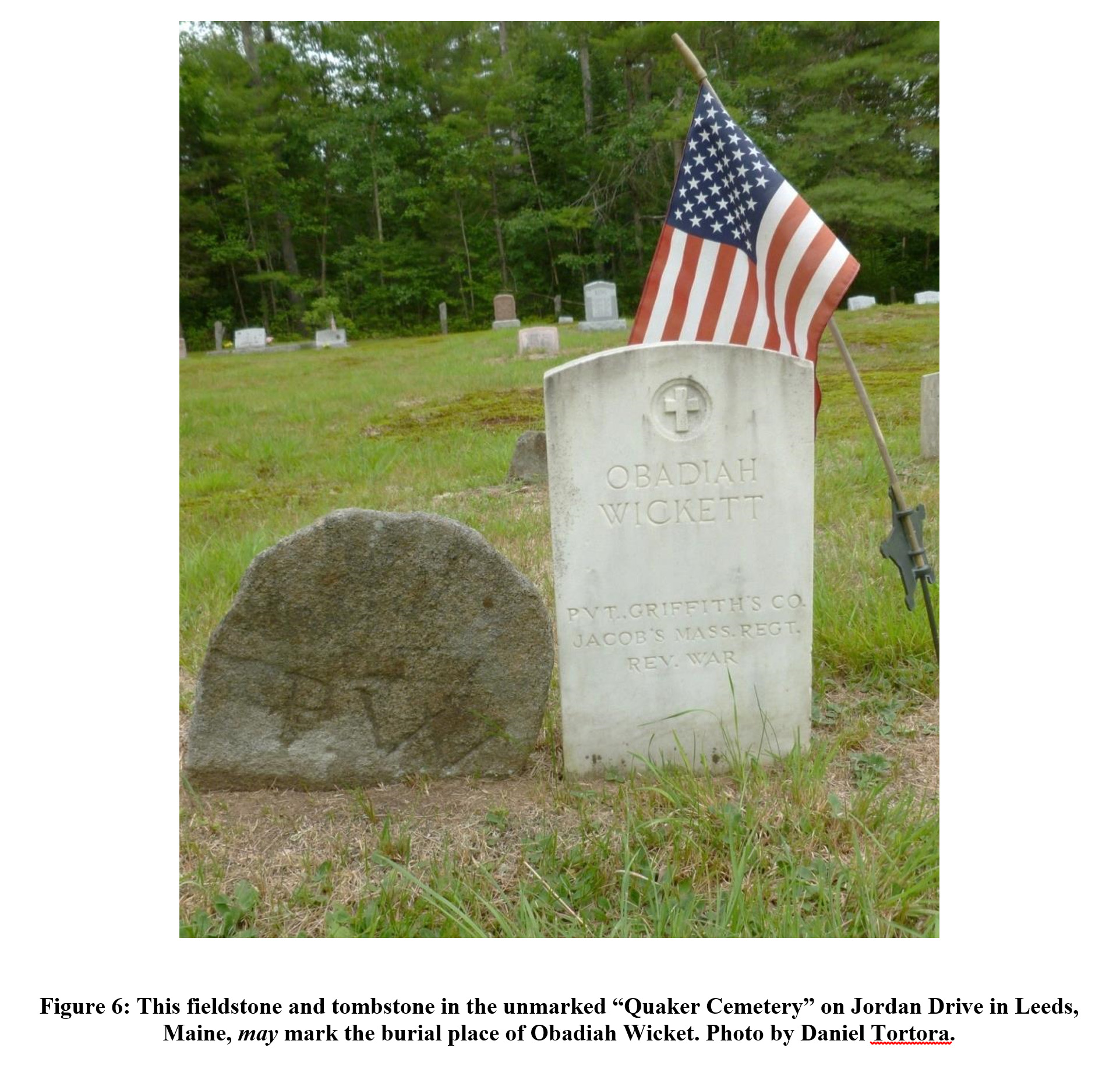

The other Massachusetts Indian pensioner was the Herring Pond Wampanoag, Obadiah Wicket (also spelled Wickett), was a household servant turned soldier. He claimed to have witnessed the execution of British spy Major John André in 1780. Thus far the evidence is inconclusive, but genealogists and local historians believe Wicket relocated to present-day Greene or Leeds, Maine (not far from present-day Auburn and Lewiston), and died there in 1819. In 1933, a town historian ordered and installed a veterans’ tombstone to mark Wicket’s reported final resting place.[13]

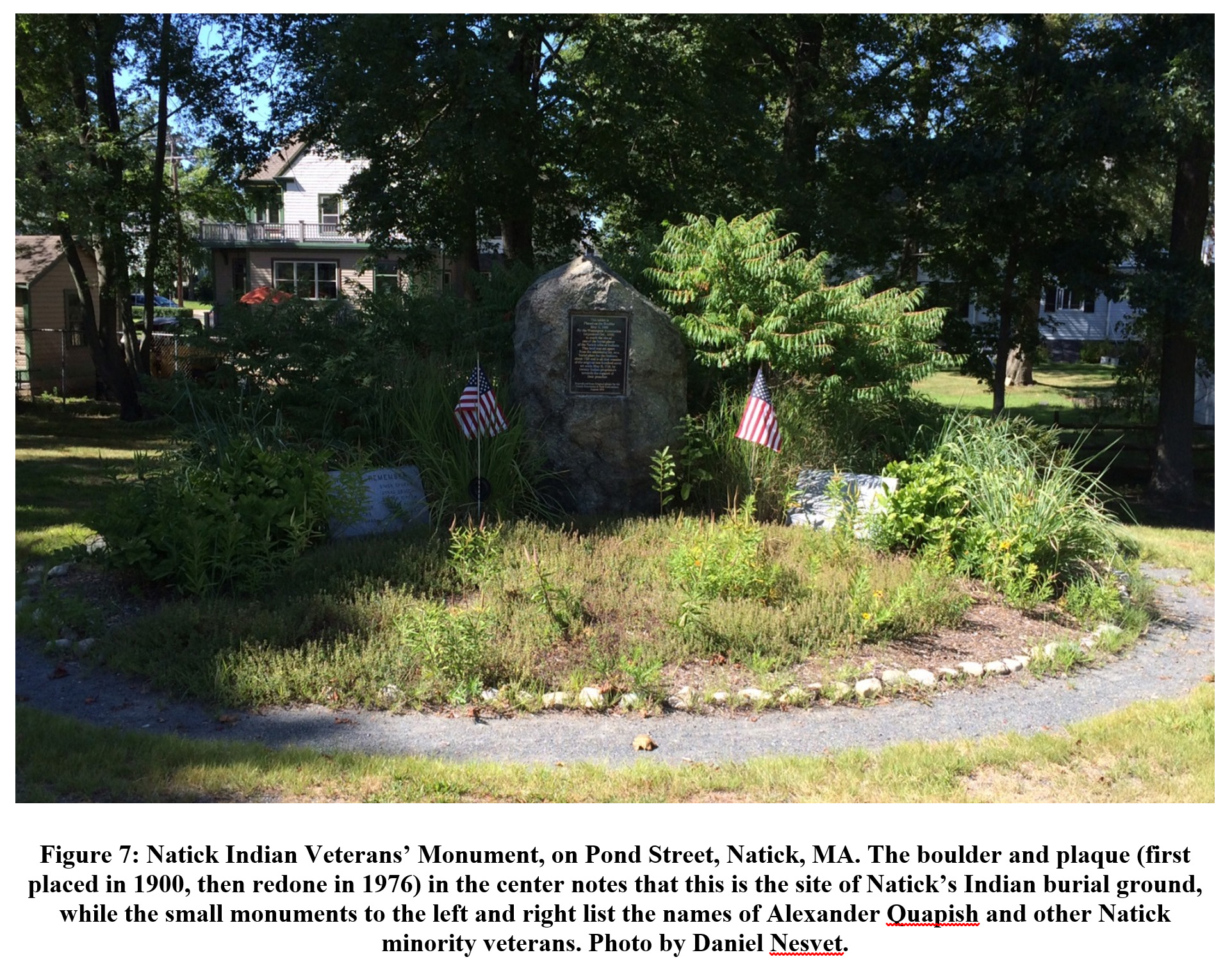

6 // The (Finally) Honored Indian: Alexander Quapish

The Natick Indian Alexander Quapish was born around 1741. A year after his wife died, and after being mustered for the Lexington Alarm, Quapish enlisted in the Continental Army in May, 1775. He served under the command of Captain Daniel Whiting in Colonel Jonathan Brewer’s regiment. He fell sick and was nursed by a teenaged soldier and his family in the “Needham Leg,” the predominantly-Indian enclave that is now part of Natick. Quapish died on March 23, 1776. His exact cause of death is unknown.[14]

After 227 years, Quapish and sixteen other Indian veterans finally got their due. In a ceremony led by Robert D. Hall, Jr., a Needham historian and a researcher for the state Veterans Affairs office, volunteers placed markers and flags throughout a cemetery containing the Indians’ remains. In 2006, descendants of the Natick Indian veterans held another ceremony and unveiled monuments listing Natick veterans of color. In 2010, Boston National Historical Park posted a student-narrated video on Alexander Quapish. And a few years later, the Indian’s terminal convalescence was referenced in artist Ted Clauson’s Needham Cares sculpture, located outside the high school in that town.[15]

While the individual stories of these Indians can be exciting, the collective reality is sobering. The eastern Massachusetts Indians who fought and died for the American cause were poor and desperate common soldiers. Following a long tradition of service to Massachusetts, they sought a better life and a share in the freedom and liberties that the United States claimed to be fighting for. Indian soldiers did not receive the acknowledgement they deserved while they were alive. After the war, widows struggled to pick up the pieces. Poverty, land loss, transiency and general mistreatment remained the norm. But the experiences of these six Native Patriots, now better understood and better commemorated, offer a glimpse into the struggles and contributions of the first Americans. And they reveal one of many moments in American history in which Indians fought alongside non-Indians to forge a better future together.

[1] National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, Minority Military Service, Massachusetts: 1775–1783 (Washington, D.C.: National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 1989), 5.

[2] Jean M. O’Brien, “‘Divorced’ from the Land: Resistance and Survival of Indian Women in Eighteenth-Century New England,” in After King Philip’s War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England, ed. Colin G. Calloway (Hanover, N.H. and London: University Press of New England), 145.

[3] Researchers disagree on the precise number of Natick Indians who served in the Revolutionary War, classifying some veterans as Indian and others as African American.

[4] Robert D. Hall, Jr., “Praying Indians in the American Revolution,” lecture transcript, February 8, 2004, http://needhamhistory.org/features/articles/indians-american-revolution/; Eric Grundset, ed., Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War (Washington, D.C.: National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 2008), 130.

[5] Jean M. O’Brien, Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650–1790 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 95; George Quintal Jr., Patriots of Color: ‘A Peculiar Beauty and Merit’: African Americans and Native Americans at Battle Road & Bunker Hill (Boston: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, 2004), 43–44, 169.

[6] Petition of Jonas and Mary Obscow, May 27, 1772, Massachusetts Archives Collection, 33:559–60.

[7] Massachusetts. Secretary of the Commonwealth, Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, 17 vols. (Boston, MA: Wright and Potter Printing Co., State Printers, 1896–1908) [hereafter cited as MSS], 11:619; Receipt for Wages, Camp at Cambridge, June 7, 1775, American Revolutionary War Manuscripts Collection, Boston Public Library; Petition of Mary Obsco[w], June 6, 1783, Massachusetts Archives Collection, 134:508.

[8] “Red Cherry, A Naval Hero,” Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine 54 (February 1920): 96. DAR researchers found no manuscript references to Jeremiah, though he does appear on a muster roll. Forgotten Patriots Research Files, Washington, D.C., Files to be Processed, Box 22.

[9] MSS, 12:116.

[10] Ibid., 15:261; Massachusetts, et al., eds., The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the State of Massachusetts, 1777–1778 (Boston: Wright & Potter, 1918), 473–74 (June 23, 1778); “The Number of the Indians belonging to Potenomacut,” December 1, 1765, Massachusetts Historical Society manuscript. Transcript posted on http://wolfwalker2003.home.comcast.net/~wolfwalker2003/potenomacut1765.pdf.

[11] Isaac Wickham, S34534; Job Tobias, B.L. Wt. 1927-100, p. 11–12; and Josiah Crocker, W14358, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Application Files, p. 23, in National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., M804, record group 15. Viewed on Fold 3; United States. Census Office, A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Service (Washington, D.C.: Blair and Rives, 1841), 27.

[12] William Apess, On Our Own Ground: The Complete Writings of William Apess, a Pequot, ed. Barry O’Connell (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992), 232.

[13] Obadiah Wicket, S34535, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Application Files, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., microfilm publication M804, record group 15. Viewed on Fold3; Albert S. Bryant to Ferd Stevens, February 2, 1939, private collection; interview with Leeds historian Marilyn Burgess.

[14] Quintal, Patriots of Color, 186.

[15] Hall, Praying Indians; Quintal, Patriots of Color, 186; Peter Schworm, “Honoring Sacrifices of ‘Praying Indians’,” Boston Globe, May 30, 2006; “Patriots of Color Alexander Quapish,” June 25, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NifJfB0-r20; “Ted Clauson: Needham Cares,” International Sculpture Center Directory, http://www.sculpture.org/portfolio/sculpture_info.php?sculpture_id=1014784.

One thought on “Indian Patriots from Eastern Massachusetts: Six Perspectives”

I am positive that the Abenaki were involved with attacks on Fort Halifax.