New Jersey Governor William Franklin is one of the forgotten major players in the American Revolution. By the fall of 1775, he was the only royal governor in the thirteen rebellious colonies who had not fled or been chased from his post by the mounting tension between the Americans and the mother country. But William’s real prestige derived from his name. He was Benjamin Franklin’s son.

Dr. Franklin, as Benjamin was known, thanks to an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh, had returned from eleven years in London earlier in the year. In the course of this controversy-filled decade, he had become the spokesman not only for Pennsylvania but for all the colonies. On shipboard he had written the longest letter of his life. It began with two deeply meaningful words: “Dear Son.” The letter described Franklin’s secret negotiations with the British government, which had convinced him that George III and the men around him were determined to subdue and humiliate the Americans. It closed with urgent advice that William should resign his royal office as soon as possible and join the resistance to Britain’s arrogant pretensions to imperial power.

To Ben Franklin’s dismay, William declined to take this advice. He told his father he felt “obligated” to the King and his government for keeping him in his office in spite of their disagreements with his father. Not even the bloody battle of Bunker Hill, which exploded six weeks after Ben arrived in Philadelphia, changed the Governor’s mind. Almost as dismaying was Ben’s discovery that a hefty percentage of the Continental Congress, which was meeting in the Pennsylvania State House, was equally reluctant to break with the king.

Soon after Bunker Hill, Ben Franklin wrote a declaration of independence and a rudimentary constitution which he called “Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union.” He was stunned to discover that the documents had horrified most of the members of Congress. Ben’s political enemies in Philadelphia pointed to the fact that his son had not resigned as royal governor and circulated a rumor that Ben was a secret agent for George III.

Late in August, Ben journeyed from Philadelphia to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, the site of the Royal Governor’s handsome house. Both men sensed their argument was coming to a climax. Neither was aware that their discussion was fatally influenced by the distant past. William was illegitimate. He had grown up in a household dominated by his viper-tongued stepmother, Deborah, while his father was absorbed by business and politics.

William’s resentment of this unhappy childhood colored everything he heard from his father. At least as important was the influence of William’s deeply religious English wife, Elizabeth, whom he had met in London when he journeyed there with his father in the 1760s. She had convinced the Governor that it would be a grievous sin to revolt against their king.

The elder Franklin was bewildered by William’s disagreement with his support of the revolution that was rumbling around them. Only 12 years ago, father and son had journeyed to Perth Amboy to install William as royal governor. Applause and approval had been showered on them from all sides. Now, a decade had turned the world upside down. The father stressed the steady escalation of the conflict and its continental nature. George Washington had come from distant Virginia to Massachusetts to take command of the “Grand American Army” besieging the British in Boston.

Ben told William the latest news from Europe – the British were hiring thousands of German troops to bolster their army. He argued that no matter how many foreign troops they hired – George III was reportedly also negotiating with the Russians – he could never conquer America. The most his army could do was set up some enclaves along the coast. The moment the King’s soldiers ventured into the interior, they would be trapped and annihilated.

The heart of Benjamin’s argument was the importance of William acting now. Timing was crucial. Congress would soon appoint generals to serve under Washington. William’s service in the French and Indian War made him well qualified for one of these commissions. If he preferred a political post, there would soon be numerous tasks he was even more qualified to undertake. When it came to national reputation, he was one of the few men in the colonies who could match George Washington.

William shook his head and argued back. He told Ben most colonists were not in favor of independence. Only a small faction favored this drastic, treasonous step. Earlier in the year, the rebels in New Jersey had formed a Provincial Congress. When they levied taxes and drafted men into a militia, a negative reaction had swept the state.

The Governor insisted that the pro-independence minority had forced the British government into acts of war, such as Bunker Hill. He flourished a letter from Lord Dartmouth, the American Secretary in the British cabinet, urging him to press the New Jersey legislature to consider a recent conciliatory proposal from Prime Minister Lord North. Finally, William scoffed at the idea that America, a country that had trouble paying its royal governors’ salaries, could win a war that would cost millions against the richest most powerful nation on earth.

Mournfully, the unhappy father rode back to Philadelphia. A few days later, William sent him copies of Lord Dartmouth’s letter, and the minutes of recent sessions of the New Jersey Assembly, in which there had been no hint of revolutionary tendencies. The Governor signed the letter, “Your ever dutiful and affectionate son.”

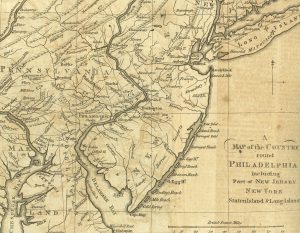

On November 15, 1775, Governor Franklin made his move. He summoned his colony’s assembly to meet in Burlington, New Jersey. He was betting on his long tenure in office, his famous name, and his frequent declarations that the rights of the people and the prerogatives of the Crown were equally dear to him. Other factors further increased his chances of success. New Jersey was largely rural. It had no big cities in which agitators could fester. Nor was there a newspaper to fan the flames of resentment.

On November 16, Governor Franklin told the Assembly that he was troubled by the “present unhappy situation of publick affairs.” He declared that he wished to say nothing that would “endanger the harmony of the present session.” He then proceeded to say a great deal that endangered the harmony of the whole American Revolution. He told the legislators that “His Majesty laments their neglecting the resolution of last February 20th.” This was the offer from Britain’s prime minister to exempt from further taxation any colony that voted to contribute its just share to the common defense of the empire.

The Governor’s father had described this so-called “Conciliatory Resolution” as the equivalent of a highwayman brandishing a pistol at a stagecoach window. But William Franklin’s solemn voice and earnest manner gave no hint of this opinion. He went on to tell the assemblymen why he had chosen not to flee to one of the British men of war that were anchored in New York harbor. He did not wish the King to think New Jersey was in “actual rebellion” as other states obviously were. Everyone knew His Majesty was taking “all necessary steps” for putting down the rebellion with the same severity that had seen the defeat of recent uprisings in Scotland and Ireland. William professed to be deeply distressed at the thought that New Jersey might be exposed to such punishment. He begged the assemblymen to persuade the people not to bring “such calamities” on their peaceful, prosperous province.

If they did not agree with him, the Governor continued, if they wanted him to depart, all they had to do was tell him. He was well aware that “sentiments of independency” were being voiced by some people. Essays in newspapers in Philadelphia and New York ridiculed those who feared “this horrid measure.” Then, with masterful persuasion, William told the assemblymen they would do their country “an essential service” if they declared their sentiments in “full and explicit terms” that would “discourage the attempt.”

Not a word was spoken against the Governor’s exhortation. William made sure this tacit agreement would continue by announcing that the King had granted a request New Jersey had been making for a decade. They would be permitted to print 100,000 pounds in bills of credit, which would serve as badly needed paper money. The assembly responded by voting to form a committee that would petition George III “to use his interposition to prevent the threatened effusion of blood” and to express their great desire for the “restoration of peace and harmony on constitutional principles.” Even more startling were resolutions sent to New Jersey’s delegates in the Continental Congress, forbidding them to vote for “any propositions …that may separate the colony from the mother country.”

It was a truly incredible performance, the incredibility magnified tenfold by its time and place, less than a half day’s journey from the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. At that seat of rebellious government, delegates discussed enlarging George Washington’s army and worried about the problems being encountered by the army they had sent into Canada earlier in the year to bring the “fourteenth colony” into their revolution. Also on the docket was advice to several colonies to form their own governments and take no more orders from royal officials. Engulfed in this ever swifter current toward independence, the congressman could not believe their eyes or ears when they heard what Governor Franklin and his assembly were doing across the Delaware River in Burlington.

It did not take a Machiavelli or a Julius Caesar to discern that if New Jersey’s petition got to George III and he bestowed still more proofs of his generosity from his ample exchequer, the chances were alarmingly good that other wavering colonies such as Maryland and New York (which had already ordered their delegates not to vote for independence) would have second thoughts about loyalty to the penniless Continental Congress.

At this point in 1775, the percentage of Americans who favored independence was still relatively small. This was especially true in New Jersey. In many counties, the voters who favored independence barely numbered a hundred. If the King had even one or two opportunities to display his generosity (based, of course, on a colony’s “submission”) the deep wellsprings of feeling for England which were still a living reality in almost every American’s consciousness would have swiftly swept the independence men into an impotent minority.

Even more probable was the instantaneous jealousy that would have seized every colony if New Jersey, New York and Maryland won special favors from the King. The Continental union might vanish in the smoke and flames of mutual recrimination, overnight. Almost singlehandedly, William Franklin was dueling his father and the rest of the Continental Congress for control of the continent.

The men meeting in Philadelphia were equally aware of the stakes. Although they had not yet agreed on where they were marching – toward independence or eventual reconciliation – they were in total agreement on maintaining a united front. The very day they heard the news of the New Jersey Assembly’s petition, they resolved unanimously that in the “present state of affairs” it would be “very dangerous to the liberties and welfare of America if any colony should separately petition the king or either house of Parliament.”

The Continental Congress appointed a three man committee to communicate this decision to the New Jersey Assembly. The committeemen were John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, George Wythe of Virginia and John Jay of New York. Dickinson had long been Benjamin Franklin’s chief political foe in Pennsylvania. Now Benjamin had to watch his enemy undertake the task of rescuing the Revolution from his loyalist son. It reduced Franklin’s power in Congress to something very close to zero. A man who could not persuade his own son to join the cause was unlikely to be respected as a political leader.

The following day, December 6, 1775, Dickinson, Wythe and Jay were in Burlington, where they asked for permission to address the assembly. Behind the scenes, Governor Franklin desperately lobbied influential members to refuse to listen to them. But this was asking too much of American legislators in late 1775. A superb orator, Dickinson soon convinced a majority that their petition was a surrender to Britain’s divide and conquer tactics. Only if they persuaded Parliament that they were not “a rope of sand” would they ever win redress of their grievances.

John Jay followed Dickinson to the podium and made a shrewd suggestion. He pointed out that Congress had already presented an “Olive Branch Petition” to Parliament earlier in the year (John Dickinson had been its writer and sponsor). The British had ignored it with the pompous assertion that Congress had no legal standing. Wouldn’t it be better to urge His Majesty and his friends to reconsider that perfectly reasonable plea for reconciliation, rather than submit one of their own? The Assembly, already uncomfortable about their rebuke from the Continental Congress, seized on Jay’s idea as a perfect out. They resolved that their petition be “referred” until the King responded to the olive branch plea.

Governor Franklin could only watch in frustration as his attempt to build a backfire against independence flickered out. He soon discovered that he had ignited another kind of blaze, crackling with suspicion and hatred, in New Jersey’s independence men. Before the year 1776 ended, a still defiant William Franklin would be a prisoner in Connecticut. His father, abandoning all hope of becoming a leader in Congress, accepted the task of going to France to persuade England’s inveterate enemy to become an ally of Revolutionary America. Ben Franklin’s triumph in this seemingly impossible assignment would have a decisive impact on America’s struggle for independence.

[This article is adapted from the author’s book The Man Who Dared The Lightning: A New Look At Benjamin Franklin (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), recently released as an ebook.]

One thought on “Governor Franklin Makes His Move”

What a tightly wound description of the fall of a potential founding father. And Fleming left the best for last: the what if. If Franklin had opted for revolution, his father might not have been sent to France. I wonder how that would have played out.