He may have beaten the British, but by the time George Washington became president, his sweet tooth (singular tooth)[i] for tasty desserts had not yet been conquered. Puddings, jellies and pies had been commonplace dessert offerings when George and Martha entertained at Mount Vernon, which they did before and after the War for Independence.

But there was one particular sweet delicacy which may have been the favorite of George Washington. The delicacy went by different names and spellings of the time, but it was more commonly referred to as “Ice Creem.”[ii]

Ice cream historians often suggest the French brought the recipe for the yummy confectionery with them to America as immigrants in the early eighteenth century. The first ice cream reference in the American colonies is from 1744: “Among the rarities… was some fine ice cream, which, with the strawberries and milk, eat most deliciously.”[iii]

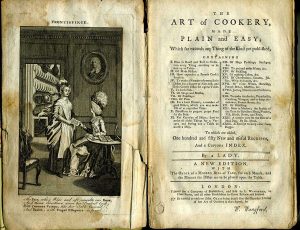

But it was the 1751 blockbuster cook book with the long name The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy; Which far exceeds any Thing of the Kind yet published by Hannah Glasse that made the recipe for ice cream widely available. It described mixing “a pint of scalding cream” with “six ounces of double-refined sugar” and “four handfuls of salt,” then placing the mixture into “a tub of ice broken small.” After “the cream is all froze up,” it is “put into the mould.”[iv] Mount Vernon Research Historian Mary V. Thompson confirms that Martha Washington had a copy of Hannah Glasse’s cookbook.[v]

Cold Facts About Colonial Ice Cream

Thompson also passed along some excellent background information on colonial-era ice cream for readers of Journal of the American Revolution:

Ice cream was initially something that only a wealthy person would be able to have. It would require the money to own at least one cow and not have to sell her milk and cream; it would require fairly large quantities of sugar (an imported commodity), as well as salt (also imported). Making ice cream also requires ice, which had to be cut on a river during the winter and placed in an ice house in the hope that it would still be around by the summer (most homes wouldn’t have had an ice house). Finally, making ice cream could take a fair amount of work and most families couldn’t afford the time for a family member or a servant to ‘waste’ making such a frivolous dish.[vi]

George and Martha’s Ice Cream

George and Martha Washington may have been introduced to the wondrous taste of ice cream before the Revolutionary War began, while the Virginia Tories and Whigs were still on speaking terms. The colonial governor of Virginia between 1768 and 1770 was Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt. He was known to have served his Williamsburg guests (such as the Washingtons) with cups of ice cream at his royal get-togethers.[vii]

After the Revolutionary War, retired General George Washington was back home on his beloved Mount Vernon estate. The taste for ice cream was catching on in the new nation and the confection was likely made at Washington’s estate. The first reference to Washington’s personal fondness for ice cream might be indicated by his May 1784 purchase of a “Cream Machine for Ice”[viii] at Mount Vernon.

Presidential Big Chill

For eight years as president, Washington had to be away from his Virginia plantation, but at least ice cream could help him cope with the separation. Records show that as president, Washington bought an ice cream serving spoon and two “dble tin Ice Cream moulds.”[ix] This was followed by “2 Iceries Compleat,” twelve “ice plates,” and thirty-six “ice pots.”[x] (An “ice pot” was a small cup used for holding the ice cream since it was more liquid in colonial times, similar to the runniness of an ice cream cone on a hot day.) Thompson speculates, “the large number of ice cream pots suggests that this was a favorite dessert at Mount Vernon, as well as in the capital.”[xi]

In late 1790, the capital of the United States moved from New York to Philadelphia. To better control the crowds of people who wanted to meet and greet the first couple, George and Marsha established two times during the week to receive guests at the “President’s House” at 190 High Street.[xii] George met men in a business-like gathering called a “levee” on Tuesday afternoons from 3:00 to 4:00 p.m. George and Martha greeted both men and women on Friday evenings from 7:00 to 10:00 p.m. in a social setting called a “drawing room.”

Various accounts of the drawing room receptions document that the ice cream was plentiful.

Abigail Adams, in Philadelphia with her husband, Vice President John Adams, wrote to her sister and twice mentioned Martha Washington’s drawing room levee and the serving of ice cream. On August 9, 1789, she wrote, “I propose to fix a Levey day soon. I have waited for Mrs. Washington to begin and she has fixd on every fryday 8 oclock… The company are entertaind with Ice creems & Lemonade.”[xiii] A year later, Abigail writes of “the Pressidents Levee of a Tuesday and Mrs. Washingtons drawing of a fryday such… She gives Tea, Coffe, Cake, Lemonade & Ice Creams in summer.”[xiv]

Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay describes a 1789 summer dinner with the President and Mrs. Washington, even though “the room, however, was disagreeably warm… The dessert was, first apple-pies, pudding, etc.; then iced creams, jellies, etc.”[xv]

Flavors? Other than the natural vanilla-like cream flavor, it was the common colonial custom to blend strawberries, raspberries, peaches, or apricots into the cream mix during the cooking. Oh, but there was one other odd flavor around then. Chef Walter Staib, host of the television show “A Taste of History” and proprietor of City Tavern in Philadelphia, passes along that Dolley Madison, a huge fan of ice cream, had her favorite flavor: Oyster ice cream.[xvi] Argh. Brain freeze.

20 Easy Steps to Make Colonial Ice Cream

If you have ever yearned to make ice cream the way George and Martha Washington would have had it made… this recipe, adapted from several colonial sources, [xvii] is for you. Trust me, you will never take a trip to the ice cream parlor for granted again.

- Fill two big buckets with pond or river ice from the chunks cut last winter and that have been storing in your dark, damp ice-house (ice cubes from your freezer will work also)

- Pour ice into a big bowl to free up a bucket

- Crack open about six eggs and separate out the yolks

- Put yolks into a big mixing bowl

- Pour pitcher of milk (somewhere around 1/3 gallon) into the bowl of yokes

- Mix milk and eggs with a bunch of wispy sticks tied together, or an electric mixer if that’s more handy

- Sprinkle in about a cup of sugar and stir the whole mixture up

- Pour milk-yolk-sugar goop into a cooking pan

- Cook while stirring until the “custard” becomes sort of thick

- Pour now-thicker mixture back into a bowl; set it aside to cool

- Fill bucket about half way up with ice

- Pour handful of rock salt (A.K.A. big salt) into the bucket of ice

- Take tin or pewter (or yeah, aluminum) “freezer”[xviii] and jam it down into the center of the ice in the bucket

- Pile ice all around the gap between the freezer and the bucket, sprinkling in more rock salt as you do it

- Remove freezer cap and pour milk-yokes-sugar concoction down into the freezer (if you want a flavor other than sort-of-vanilla, add some cut-up fruit or jam at this point)

- Put freezer cap back on and then spin the freezer cylinder around in a circle inside the ice bucket; every so often, take cap off and stir with a spatula; keep doing this until ice-creamy thick

- Take freezer out and spatula the ice cream into a bowl (hurry, it melts quickly)

- OPTIONAL: Scoop ice cream out and put into metal molds to make ice cream look like fruit in wicker baskets or stalks of asparagus

- Bury sealed molds of ice cream back into salted ice and let them continue to harden

- When ready to serve, disassemble the molds and place the ice cream sculptures onto a serving plate; watch hot colonial people in the summer go crazy over this cold, sweet delicacy

Click here to watch how Historic Foodways Journeyman Rob Brantley makes ice cream in the kitchen at the Governor’s Palace, Colonial Williamsburg.

Thanks to Mary V. Thompson, research historian at The Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon, for her research assistance on this article.

[i] Ron Chernow, Washington, A Life (New York: The Penguin Press, 2010), 439. “By the time of his presidential inauguration in 1789, he had only a single working tooth remaining.”

[ii] Stewart Mitchell, ed. New Letters of Abigail Adams 1788-1801, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1947), 19. Abigail Adams to her her sister, August 9, 1789 at https://archive.org/stream/newlettersofabig002627mbp#page/n65/mode/1up (accessed Feb. 17, 2014).

[iii] The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. March 27, 2008 http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50110937 (accessed Feb. 21, 2014).

[iv] A Lady [Mrs. Hannah Glasse], The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy; Which far exceeds any Thing of the Kind yet published (London: W. Strahan, &c, 1776), 347-348. This work was reprinted and revised for decades in Great Britain and America since it first appeared in 1747. The ice cream recipe first appeared in the 1751 edition and remained the same in later editions.

[v] Stephen McLeod, ed. Dining with the Washingtons: Historic Recipes, Entertaining, and Hospitality from Mount Vernon (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2011, for the Mount Vernon Ladies Association), 32.

[vi] Email text from Mary V. Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., research historian at The Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington, Mount Vernon Estate and Gardens, to this article’s author; Feb. 21, 2014.

[vii] Louise Conway Belden, The Festive Tradition: Table Decoration and Desserts in America, 1650-1900 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983), 145.

[viii] A Mount Vernon ledger account for May 1784 shows that purchase in the amount of £1.13.3 (one pound, thirteen shillings, and three pence), “George Washington’s Mount Vernon: Ice Cream” http://www.mountvernon.org/educational-resources/encyclopedia/ice-cream , (accessed Feb. 21, 2014); Ledger B (unbound photostat, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association), 198a.

[x] Susan Gray Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1982), 124, 126, 128, and 145.

[xiii] Abigail Adams to Dear Sister, Richmond Hill, August 9, 1789, Stewart Mitchell, ed. New Letters of Abigail Adams 1788-1801, 19.

[xiv] Abigail Adams to Dear Sister, Richmond Hill, July 27, 1790, Stewart Mitchell, ed. New Letters of Abigail Adams 1788-1801, 55.

[xv] The Library of Congress, Journal of William Maclay, United States Senator from Pennsylvania 1789-1791. August 27, 1789. 137-138; (accessed Feb. 19, 2014) http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llmj&fileName=001/llmj001.db&recNum=148&itemLink=r%3Fammem%2Fhlaw%3A@field%28DOCID%2B@lit%28mj0014%29%29%230010008&linkText=1

[xvi] PBS Food Feature, Ice Cream: An American Favorite Since the Founding Fathers, http://www.pbs.org/food/features/ice-cream-founding-fathers/ (accessed Feb. 23, 2014).

[xvii] This recipe was inspired by reading a variety of period and contemporary recipes for colonial ice cream. The sources were:

Thomas Jefferson’s ice cream recipe at the Library of Congress: The Library of Congress, American Treasures, Manuscript Division, Jefferson’s Recipe for Vanilla Ice Cream, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/tri034.html (accessed Feb. 22, 2014) ;

From page 168 in The Art of Cookery (referenced by Mount Vernon from the version owned by Martha Washington) : A Lady [Hannah Glasse], The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy; Which far exceeds any Thing of the Kind ever yet Published, facsimile (Totnes, Devon, England: Prospect Books, 1995), 168.

Elizabeth Raffald, The Experienced English House-Keeper. (Manchester, England: J. Harrep, 1769). 228.

Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Spring 2010, “Some Cold, Hard Historical Facts About Good Old Ice Cream”, http://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Spring10/icecream.cfm (accessed February 19, 2014).

Recent Articles

Teaching About the Black Experience through Chains and The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

Recent Comments

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

Sorry I am not familiar with it 2 things I neglected to...

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...