Peter Livius, chief justice of the province of Quebec and former justice of New Hampshire, wrote a letter on June 2, 1777 to American Major General John Sullivan in an effort to get Sullivan to turn to the British cause.[1] Livius thought Sullivan was the commander at Fort Ticonderoga.[2] Livius believed Sullivan had lost his fervor for the patriot cause because of his having been captured the previous year on August 27, 1776 during the Battle of Long Island and since he agreed to be the bearer of Lord Howe’s peace overtures to Congress in order to get himself exchanged.

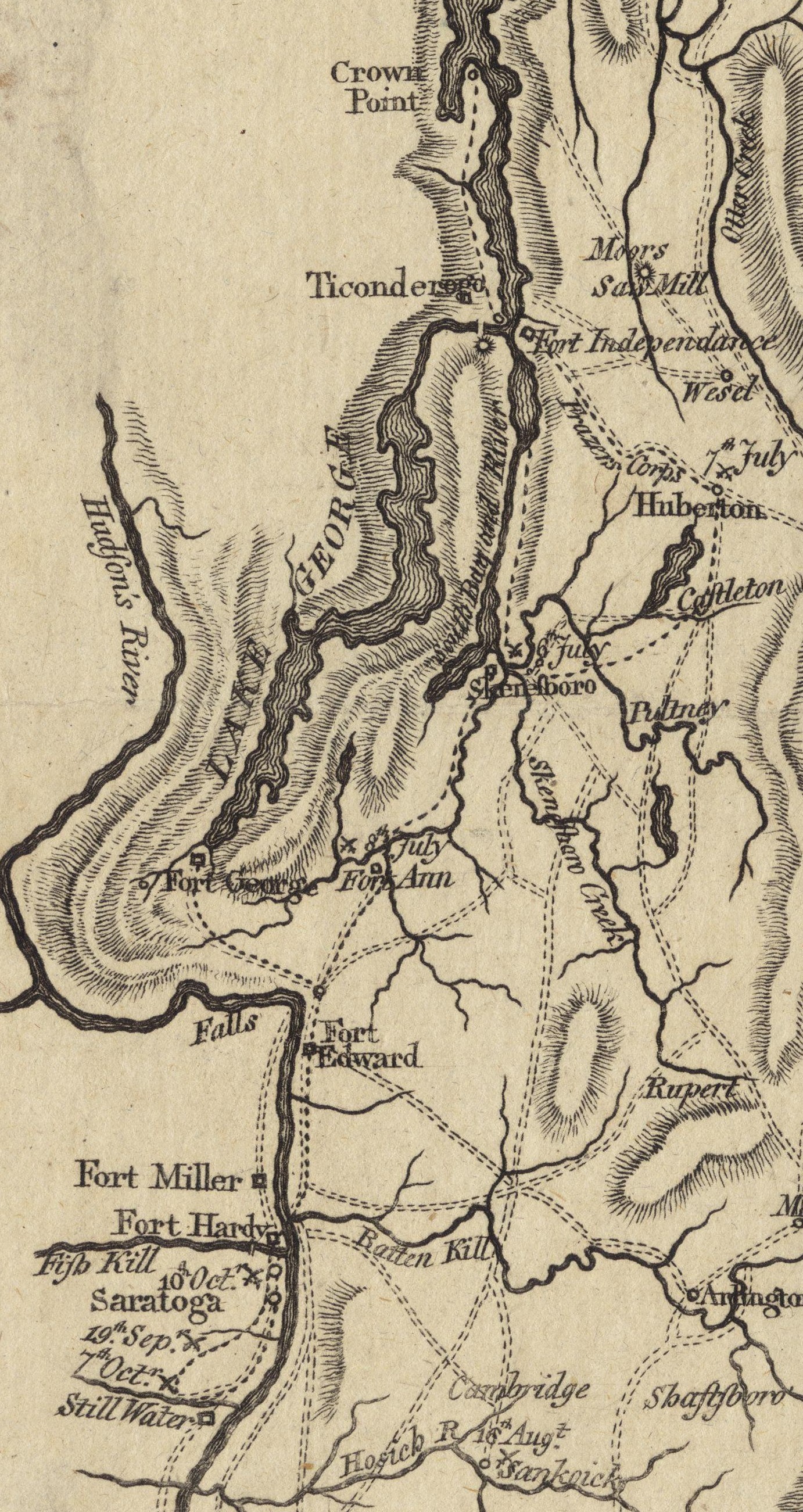

General John Burgoyne had arrived in Quebec in March 1777 and been appointed to command the northern British army in America. He was preparing his army for an expedition to divide the colonies by controlling the Hudson River area of New York. If Sullivan could be turned to the British side then Fort Ticonderoga could be taken without resistance. The fort is strategically located overlooking the narrow passage between Lake Champlain and Lake George in northern New York. Livius wrote to Sullivan that he would be pardoned, amply rewarded, and save his property from being confiscated if he turned over the fort. He told Sullivan that he could write to him or write to General Burgoyne but to sign with Livius’s name and Burgoyne would know it came from Sullivan.[3]

Livius entrusted William Amsbury with the task of delivering the letter to Sullivan. Amsbury, in the company a man named Adams who appears to have been on his own secret mission, left Montreal on June 4 with letters to people in the United States and a large amount of money.[4] They traveled to Saint John, which is north of Lake Champlain on the Richelieu River, and left there on the morning of June 5.[5] At Saint John they received a British pass to go beyond their lines.

In order to travel undetected Amsbury took an old Indian trail from Canada that the Indians used to make their attacks on the frontier settlements on the Connecticut River. Amsbury made it as far as the Onion River in Vermont where an American scouting party captured him.[6] Adams was reportedly captured at Sabbath Day Point.[7]

Amsbury was taken to Fort Ticonderoga and turned over to Major General Arthur St. Clair who had taken command of the Fort on June 12, 1777. St. Clair wrote to Major General Philip Schuyler the next day about Amsbury, “I have the strongest suspicion of his being a spy and secured him as such.” He also thought “there was no method more likely to procure them an easy reception” than having Adams and Amsbury provide the intelligence of General John Burgoyne’s arrival.[8]

Amsbury claimed to be searching for plans of the country that he claimed were at a house in the area. When Amsbury was captured he had some gold and silver and a considerable sum of Continental currency that was wrapped in a letter he was carrying. St. Clair sent Amsbury on June 15, 1777 by way of Lake George to Schuyler at Saratoga, New York.[9]

General Schuyler reminded Amsbury that the pass he carried was enough to hang him: it was from “M[ichael] Kirkman, Major of Brigade of British Infantry at Saint John, to the commanding officer at the Isle aux Noix or any detached parts of the army” and included the phrase, “the bearer [Amsbury] and his companion [Adams] being employed on Secret Service.”[10] Schuyler then ordered Amsbury to be sent back to the guard, placed in irons, and taken to Albany. After some time Amsbury pleaded for an audience with Schuyler which was granted. Schuyler cautioned Amsbury that if he provided frivolous information the execution would be accomplished. Under threat of being hung by Schuyler, Amsbury opened up and stated that the British forces were approaching St. John on the Richelieu River and were to advance under General Burgoyne; that a detachment of British troops, Canadians, and Indians under Sir John Johnson was to penetrate the country through the Mohawk Valley; also that the Canadians were averse to taking up arms but were forced to do it; and that no reinforcements had arrived from Europe.

Amsbury admitted to being on a secret errand. He admitted to smuggling a letter intended for Major General John Sullivan in a false bottom of a canteen. Amsbury said that someone named Michael Shannon wrote the letter. Shannon’s name was found on a separate piece of paper that General St. Clair said Amsbury was reluctant to surrender; St. Clair believed that this piece of paper was a signal by which Amsbury was to be known upon his return. Amsbury stated that a “Mr. Levy, a Jew, had spoken to him to carry some things to Ticonderoga. He advised that on the 4th, Judge Peter Livius of Montreal had given him a canteen with a false bottom concealing a letter for General Sullivan. When questioned about the canteen, he advised that while at Fort George, he gave it to an American officer’s servant to fill with water.”[11] However, the servant had not returned with the canteen before Amsbury was taken away.

General Schuyler sent Second Lieutenant Bartholomew Jacob van Valkenburgh of the 1st New York Regiment to retrieve the canteen from Fort George.[12] He was to bring the canteen under armed guard to Fort Edward, New York where Schuyler would meet him. Van Valkenburgh retrieved the canteen from Lieutenant Colonel Cornelius Van Dyke Dyck of the 2nd New York Regiment “who separated part of the wire from the false bottom to see whether it was the canteen I was sent for, and who after taking out this letter, and letting out some rum, returned it into the canteen without breaking the seals” that closed the letter.[13]

Van Valkenburgh delivered the canteen at 10 a.m. on June 16. General Schuyler opened the false bottom of the canteen in the presence of observers and they signed the letter that was removed as witnesses.[14]

General Schuyler sent a letter to General George Washington that very day. He advised Washington that he would send a reply back to Chief Justice Peter Livius as if it had come from General Sullivan. On June 17, 1777 at Albany, New York, Schuyler sent a letter to the Continental Congress advising them of his plan. General Sullivan was at Rocky Hill, New Jersey when he was informed by Washington of the secret letter in the canteen. He reconfirmed that it was in the handwriting of the “infamous Mr. Livius.”

On June 20, 1777 the response was ready and claimed General Sullivan’s disapproval of the actions of Congress and a loyalty to the king. It requested instructions from General Burgoyne and provided exaggerated troop strengths for the Continental Army in New Jersey and New York. Schuyler included some significant information received from other spies from Montreal. This information could be verified by Peter Livius thereby giving credence to the information in the response. The letter indicated that correspondence should be directed to Major Henry Dearborn who was well known by Peter Livius to the extent that Livius had twice made personal loans to Dearborn. Major Dearborn knew of the message as he was one of the officers who had approved of its contents. A copy of the response was sent to Congress on June 25, 1777.[15]

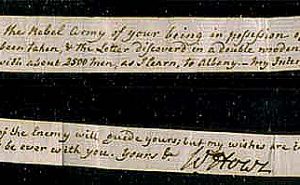

A soldier who was to have received physical punishment for attempting to desert to the enemy was duped into escaping and taking the letter. It is unknown if the letter ever reached its destination or if a response was ever sent. However, General William Howe sent a message on July 17, 1777 from New York City to General John Burgoyne, written on two strips of paper that were rolled and hidden in the hollow shaft of a quill pen, which warned him that “there is a report of a messenger of yours to me having been taken, and the letter discovered in a double wooded canteen.”[16] Howe’s warning of Livius’s letter to Sullivan having been intercepted would explain why no response was received by Major Henry Dearborn from General Burgoyne.[17]

What happened to Ambsbury’s companion, Adams? Since he was considered to be innocent, he was probably released. What happened to William Amsbury? It appears he may have escaped. There is a private William Amsbury who was listed in a troop return for the Queens Loyal Rangers, a loyalist regiment, dated December 14, 1780; it may be the same person. That William Amsbury with a woman and child were receiving rations in 1780 and 1781 at Saint Johns.[18]

I first wrote this story in my book Invisible Ink Spycraft of the American Revolution (Yardley, PA, Westholme Publishing, 2010). Since that time I have discovered some additional information which is included here.

[Featured image at top: Detail of a map of Fort Ticonderoga as it appeared in 1758, when it was named Fort Carillon. Source: New York Public Library]

[1] Peter Livius was born July 12, 1739 in Lisbon, Portugal He moved to New Hampshire in 1763. L.F.S. Upton, “LIVIUS, PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003), http://www.biographi.ca/bio/livius_peter_4E.html, accessed February 5, 2014.

[3] For the complete text of Livius’s letter see New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, September 1, 1777, p.2, c. 2-4.

[4] Amsbury was paid per order of General Burgoyne on June 2, 1777 12 pounds 10 shillings for going to General Sullivan. “Account of Cash disbursed by Lieutenant Colonel John Peters to sundry Persons for Government Services on the Expedition Commanded by Lieutenant General John Burgoyne,” Great Britain, British Library, Additional Manuscripts, No. 21827, folio 18, at http://www.royalprovincial.com/military/rhist/qloyrng/qlrdisb.htm accessed February 13, 2014. At this writing, nothing is known about Adams including his first name. It appears that Adams did not know of Amsbury’s secret mission.

[5] Philip j. Schuyler, June 15, 1777 at 4 p.m., American Intelligence Report. General Correspondence, George Washington Papers (GWP), Library of Congress.

[6] The Onion River today is known by its old Indian name as the Winooski River. At some time prior to the American Revolution it had also been known as the French River.

[7] Adams and Amsbury must have separated; Adams was captured at Sabbath Day Point south of Fort Ticonderoga on Lake George, New York. General Arthur St. Clair at Ticonderoga to General Schuyler, June 13, 1777, in William Smith, The St. Clair Papers (Cincinnati, Robert Clark and Company, 1882), 400.

[8] General Arthur St. Clair at Ticonderoga to General Schuyler, June 13, 1777, Smith, The St. Clair Papers, 396-399.

[9] Philip j. Schuyler, June 15, 1777 at 4 p.m., American Intelligence Report. General Correspondence, GWP.

[10] The pass was signed by M. Kirkman, Brigade Major. There is a Brigade Major Michael Kirkman who is a Captain of the 21st Regiment. Worthington Chauncey Ford, British Officers Serving in America 1754-1774 (Boston, Brooklyn: Historical Printing Club, 1897), p. 106. Isle aux Noix is a 210 acre island in the Richelieu River south of Saint John. The French built a fort there in 1759.

[11] The name is sometimes spelt Tierce. Philip j. Schuyler, June 15, 1777 at 4 p.m., American Intelligence Report. GWP and Francis Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, April 1775 to December 1783 (Washington, DC: Rare Book Shop Publishing, 1914), 535, 543.

[12] Heitman, Historical Register, 557. He identified Lieutenant van Valkenburgh as Second Lieutenant Bartholomew Jacob Van Valkenburgh of the 1st New York.

[13] Van Valkenburgh identified Colonel Dyck but Heitman, Historical Register, 408 identifies him as Lieutenant Colonel Cornelius Van Dyke of the 2nd New York Regiment. Bar. J. V. Valkenburgh, Lieut[enant] to John Sullivan, June 16, 1777. New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, September 1, 1777, p.2, c. 4.

[14] The witnesses were Captain Benjamin Hicks of the 1st New York Regiment; John Lansing Jr., Military Secretary to General Schuyler; Colonel Henry B. Livingston, aide-de-camp to General Schuyler; and Captain John Wendell of the 1st New York Regiment. New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, September 1, 1777, p.2, c. 4.

[15] Philip J. Schuyler to Continental Congress, June 25, 1777. Papers of the Continental Congress, No. 153, III, folio 172. Schuyler’s letter was received in Congress on July 3, 1777. Worthington Chauncey Ford et al, Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington, DC), vol. 8, 527.

[16] William Howe to John Burgoyne, July 17, 1777, Gold Star Box, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

[17] For a transcript of Howe’s letter see John A. Nagy, Invisible Ink: Spycraft of the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2010), 106.

[18] Return of the Corps of Queens Loyal Rangers commanded by Lieut. Colonel John Peters, Quebec December 14, 1780, http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~qceastwn/archives/QueensLoyalRangers.html, accessed February 7, 2014 and Locator 2324—Amsbury, Herbert Clarence Burleigh Fonds Collection, Queens University Library, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

8 Comments

What a wonderful story. I had never heard of this incident during over six intense years of research on Burgoyne’s Loyalists. My only note being that Amsbury had received a cash advance for a Secret Service mission on 02Jun77.

Gavin K. Watt, “The British Campaign of 1777, Volume Two – The Burgoyne Expedition – Burgoyne’s Native and Loyalist Auxiliaries (Milton, ON: Global Heritage Press, 2013)

William Amsbury later had an adventurous life in the Canadian Secret Service. He and John Lindsay, both private soldiers in Captain Justus Sherwood’s company of Queen’s Loyal Rangers (Sherwood was at the time the officer commanding the Secret Service) were sent to Portsmouth NH in 1781 where a new ship was under construction for John Paul Jones. Upon arrival, they discovered the vessel laid on the same stocks on Langdon’s Island in the Piscataqua River from which Jone’s sloop “Ranger” had been launched in March 1777. This dockyard had also built the HMS “America” in 1749 – the vessel which had transported the Acadians into exile.

This new ship was said to be the largest laid down in America since the beginning of the war. She was designed to be 108.5 feet long on the upper deck, 50 feet maximum breadth and 23 feet in depth. She would mount 30X8pdrs on the lower deck and 32X12pdrs on the upper and 14X9pdrs on the quarter deck. Her complement was to be 626 officers and men.

The agents were told that the vessel was being constructed at the expense of France and that Jones’s commission was from that country as well. When complete, the ship would join the French Line.

Lindsay reported that Jones was “a middling sizd man of dark complexion, dressed very grand with two gold aupletes on his coat. he rides out every day in his coach which is very like Col: [Barry] St. Leger’s.”

When intelligence was received that the British were going to make an attempt to destroy the ship, Jones requested that the State of New Hampshire provide a guard. When no action was taken, Jones paid from his own pocket for a guard of carpenters to be mounted every night. It is likely that Lindsay and Amsbury were members of this guard. In their report, they explain why they were unable to fulfill their mission.

Despite being started in 1779, the ship’s construction was dragging badly and the French guns had not yet been delivered. A single anchor had arrived in a Swedish ship, but the internals were only half finished. Although the agents could have lit a number of fires, they recognized the hull would not burn well and undoubtedly the fires would be easily doused before doing much harm. Jones bemoaned that his vessel would not be fit to launch before the next winter. Carpenters were very scarce, which must be the explanation that the loyalist agents were so readily employed. They were able to excuse themselves by claiming a need to go to Boston to pick up wages owed to them and promising that they would return with more craftsmen. One of the final lines in their report stated, “We wish to be sent again, & if we do not succeed we will not expect any pay….”

Upon their return to Canada, Governor Frederick Haldimand had the two men kept on short notice to make another attempt, but a cessation of hostilies came before they could be sent again.

The ship launched in 1782 and was named “America” before being turned over to France. As it transpired, Jones never sailed in the “America” and soon entered the service of the Czar of Russia.

For complete details of this venture, see Hazel M. Mathews, “Frontier Spies” (Fort Myers: self published, 1971) For Lindsay’s report of 17Aug82, she cites — Library and Archives Canada, Haldimand Papers, (AddMss21837, part 1) B177-1, 443.

Amsbury and his family settled at Cataraqui Township No.2 (Ernessttown) in 1784 – currently Bath, Ontario. A John Lindsay and his wife were also settled at CT2 by 1786.

Gavin Watt

Thanks for the comment and the information on Amsbury’s later adventures. The payment amount to Amsbury of 12 pounds 10 shillings is in endnote 4 which gives the amount and source of the information. There are a number of spies involved with Burgoyne.

Enjoyed your article, but must confess that I was particularly intrigued to learn that the identity of Amsbury’s companion, Mr. Adams, still remains unresolved.

Prior to the reading of your article, I had been researching a subject whose identity, like that of your Mr. Adams, had never truly been confirmed. I believe that I have rather conclusively resolved my issue, and, in so doing, may also have solved your mystery as well, as both men appear to be one in the same. To effect the identification in question, however, it will be necessary to reassess St. Clair’s report to Schuyler of June 13th, the source you cite as evidence for statements made in regards to the initial capture of Amsbury and Adams by American forces at that time.

In explanatory note [7] to your text, you state that Adams and Amsbury must have separated at some point during the course of their journey, since Adams was captured at Sabbath Day Point south of Ticonderoga on Lake George and Amsbury was taken at Onion River. As a consequence of that separation, you concluded that Adams “appears to have been on his own secret mission. “ (1)

St. Clair’s opening statement to Schuyler in the June 13th report informed his commander of the capture of two prisoners and served as an introduction to the information he had obtained from them:

Here follows the substance of the information given by two men from Canada, taken prisoners by one of our parties on Onion River. (2)

St. Clair has specifically stated here that “ one “ party had been responsible for the capture of two prisoners both of whom were taken at Onion River. There is no indication that the two men had separated and had been captured individually.

As a post script to the same report, St Clair, does make reference to Adams’ capture at Sabbath Day Point, but the omission of a key element of that citation in your article essentially alters the intended meaning of the reference made. The full citation reads as follows:

Adams, the other of the prisoners, seems to be an innocent fellow, and whom Amsbury brought off with him without knowing his errand; he was taken by Mackay at the Sabbath-day Point. (3)

St. Clair’s statement is a specific reference to Adams’ capture on March 20th, 1777 by Captain Samuel MacKay’s reconnaissance party, not to his capture by an American party in June. As this is critical to the positive identification of Mr. Adams, an additional supporting citation by Col. Thomas Marshall, commanding officer of the 10th Massachusetts Regiment, and present at Ticonderoga at the time the prisoners were brought in, makes the following statement:

Last Thursday Two prisoners were brought in, the One a Soldier that was taken last Spring at Sabath day point, and had deserted from the Enemy, the other Man has a letter directed to Genl. Sullivan . . . (4)

Marshall’s account clearly defines the time of Adams’ capture at Sabbath Day Point as the preceding spring, thereby clarifying the reference St. Clair had made to the event in his June 13th report. The affirmation of Adams as a Sabbath Day Point prisoner further allows a resolution of the mystery regarding this man’s christian name. Referring to the “ List of prisoners taken by Captain MacKay between Ticonderoga and Fort George in March 1777, “ there is but one man listed by the name of Adams who was taken prisoner at Sabbath Day Point and conveyed to Canada by Captain MacKay – his first name being James. (5)

Consequently, Amsbury’s mysterious companion would appear to be Private James Adams, enlisted on March 9th, 1777 as a fifer in Capt. John Graham’s 2nd company of Colonel Van Schaick’s 1st New York Regiment. I would be most interested in your thoughts regarding same.

(1) John A. Nagy, “ British Spy Plot to Capture Fort Ticonderoga in 1777, “Journal of the American Revolution, Feb. 19th, 2014. Accessed March 1, 2014,

https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/02/british-spy-plot-to-capture-fort-ticonderoga-in-1777/

(2) General Arthur St. Clair at Ticonderoga to General Schuyler, June 13, 1777, in William Smith, The St. Clair Papers (Cincinnati, Robert Clark and Company, 1882), 1:396.

(3) General Arthur St. Clair at Ticonderoga to General Schuyler, June 13, 1777, Smith, The St. Clair Papers, 1:400.

(4) Thomas Marshall to Samuel P. Savage, June 17, 1777, Savage Papers, 1703-1779, in Vol. 44 of Proceedings of Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston, Mass. Hist. Soc., 1911), 692.

(5) Frederick Haldimand, Frederick Haldimand Papers, 1756-1791, “Secret Intelligence From Various Parts, n. d., 1775-1784, “ British Museum Manuscript Group 21. Additional Manuscripts 21841, (B-181), (Digitization by Library and Archives Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada), 1:58.

Michael Bennett

When I wrote the article I hoped that someone would be able to complete the missing information which you did. I was not aware of Colonel Marshall’s letter to Samuel P. Savage. The citation from Colonel Marshall placing Adams capture at Sabbath Day Point last spring changes the time frame of events. Without knowledge of the letter, I could not resolve them being captured so far apart as well as the timing. It now makes the time line fall into place. Just want to clarify that Samuel Mackay being reference is of the Loyal Volunteers. The information you provided identifies Adams as Private James Adams. I want to thank you for the information.

The ‘Adams’ traveling with William Amsbury is Dr. Samuel Adams. He was given a grant at Lake George called the Sabbath Day Point patent. Dr. Adams scouted for General John Burgoyne and provided information to the British on fortifications and troop strength at Fort Ticonderoga on March 21, 1777.

In reality, Dr. Adams was a double agent. He is the brother of Col. Andrew Adams of Connecticut, who was a congressman and signer of the Articles of Confederation and the first Chief Justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court. A book is in progress called Double Agent: Dr. Samuel Adams. It is due to be published in late 2019 or early 2020.

After having read your post, Doug, I found myself wondering whether you were aware that there were two gentlemen by the name of Samuel Adams residing within approximately eighty three miles of one another during this time frame; i.e. Samuel Adams the doctor and Samuel Adams the innkeeper.

Samuel Adams the doctor, who you mention as having been Amsbury’s companion with roots in Connecticut, left his home state in 1764 and settled in Arlington, Vt, where, over the next nine years, he eventually expanded his holdings to over 700 acres.

Samuel Adams the innkeeper was an Irish emigrant who came to America in 1754, initially residing in the area of Albany, NY. In 1762 he removed to Lake George, and two years later submitted a petition for a land grant of 500 acres which came to be known as the Sabbath Day Point patent that you mention. The location of his property being located roughly mid-way between Forts George and Ticonderoga, it was an ideal camping spot for travelers making the journey between the two posts, and Adams was persuaded to open an inn here for that purpose. It is said his “House of Entertainment” was open for business sometime in 1765.

The information on American fortifications and troop dispositions at Fort Ticonderoga dated March 21, 1777 that you mention was not the consequence of a scout performed by Dr. Samuel Adams for Gen. Burgoyne (Burgoyne was actually in England in March). Samuel Adams the innkeeper and two companions were captured by Samuel MacKay upon the latter’s arrival at Lake George on March 19th, and Adams witnessed MacKay’s ambush of Captain Baldwin and Lieutenant Henry’s party early the next morning as a prisoner. As MacKay executed his withdrawal from the area, he noticed that Adams the innkeeper was having difficulty keeping pace with the column. Fearing that he would be killed by the Indians for slowing the withdrawal, MacKay halted his retreat on March 21st, and offered to release Adams (who he knew personally) if he would provide a written and signed statement describing the condition and strength of the American position at Ticonderoga. Adams agreed, and this is the document which you refer to, which, I assume you found in the Haldimand Papers.

As interesting as all this might be, however, none of it actually confirms Dr. Samuel Adams as being Amsbury’s companion in June.

Michael: There are at least 7 men with the name Samuel Adams that play a part in our story.

Judge Samuel Adams (1706-1788). He is the father of Dr. Samuel Adams, loyalist and Chief Justice and Colonel Andrew Adams.

Samuel Adams, illegitimate (1726- ). Judge Samuel’s first son born out of wedlock. Not connected with the events around Lake George. Fought in the 7 Years War.

Governor Samuel Adams (1722-1803). Cousin of President John Adams; they are of the line of Henry Adams of Braintree, Mass.

Dr. Samuel Adams, loyalist (1730-1810). Son of Judge Samuel. Lead the life of a double agent. He was a spy for General Burgoyne, his 4 page report on the conditions of Fort Ticonderoga dated March 21, 1777.

Fo. 220 I Samuel Adams solemnly promise

to give true answers to every question demanded

by Captain Mackay and to give true information

of the different posts, fortifications, &c. in and

about Tyconderoga so help my God.

March 21, 1777

(signed) Samuel Adams

Found in the Haldimand Papers. Report gives 4 detailed pages of information.

Dr. Samuel Adams (1751-1788), son of Governor Samuel Adams. Patriot; surgeon; at the Battle of Bunker Hill. This Dr. Samuel Adams is not critical to events around Lake George and Fort Ticonderoga, but is mentioned because he too is known as a Massachusetts doctor and surgeon caring for Continental troops. He graduated Harvard in 1770; was trapped inside Boston and held by the British for a time; was in poor health most of his life; died at age 36 after returning to Boston in 1788.

Dr. Samuel Adams (1744-1819), patriot; stationed at Fort Ticonderoga in 1776. Married 1st Abigail Jordan. She deceased in 1774 and Samuel courted Miss Sarah Preston (1749-1787), daughter of Remember Preston and Sarah Davis. He wrote 6 letters to Sarah while at Fort George and Mount Independence, New York. There are a total of 32 letters written from Dr. Samuel Adams to his fiancé, Sarah Preston, between 1775 and 1781 held by The David Library of the American Revolution in the Sol Feinstone Collection. For example, his letter of 5 Oct 1776 “informs her that his detachment returned to “Ti” [Fort Ticonderoga,New York] but that he remained behind to care for the many sick; mentions that there is little expectation of engaging the enemy this season.” Descends from Henry Adams of Braintree, Mass.; cousin of the President.

Samuel Adams, immigrant inn keeper; suggested by Michael Bennett. No known information.

With regard to the patent at Sabbath Day Point, in the History of Warren County is “Adams—On a little tract, called Sabbath-day Point, the maps in the Surveyor-General’s office have the name of Andrew Adams.” This is Samuel’s brother, Colonel Andrew Adams.

Dr. Sam, loyalist, went by Samuel Adams for all activities and recorded events around Lake George. There were definitely two Dr. Samuel Adamses near Fort Ti, Dr. Samuel Adams, loyalist spy, and Dr. Samuel Adams, patriot (1744-1819).

Are there two spies named Samuel Adams operating around Ticonderoga at the same time?

Unlikely. In 1776, Colonel Jeduthan Baldwin, chief engineer for Fort Ticonderoga, crossed paths with Dr. Samuel Adams. Quoting from Baldwin’s journal:

“Octor 9 [1776] Paying off the workmen. A Court martial Sot for the trial of the Onion River Prisoners Genl St Clear Genl Bricket & the Pay Master Genl. [Colonel John Pierce] Dind with me. After dinner we went over to the landing to Mr. Adams, drank Tea.”

Colonel John Pierce is a personal friend of Colonel Andrew Adams. There are a series of 11 letters that Colonel Pierce wrote to Colonel Adams between August 26, 1775 and May 1, 1778. Quoting from one of them:

and am more

sensible of the kindness of being considered in your Friend=

ship and receiving your Letters, since [I] am surrounded

by a set of ignoble wretches, in whose conversation I can

pass no pleasure, or profit, which renewes my obligation

of gratitude and makes me form the generous wish that

my conduct may be able to deserve it.

Colonel Baldwin and other distinguished and high ranking American officers dined frequently with Samuel Adams at Sabbath Day Point, including the fort commander, General Anthony Wayne. We know that Dr. Samuel Adams, loyalist was a spy for Burgoyne, but there is no evidence that there was another person named Samuel Adams who was a spy in that area at the same time. I feel quite confident that the spy operating around Lake George and Fort Ticonderoga was Dr. Samuel Adams, loyalist of Arlington, Vermont.

I think the reason that McKay released Samuel Adams was that they were well acquainted due to their loyalist relationship in the British military. There were 5 units of loyalists including Peters, McAlpin, McKay, Adams, and Jessup. Adams Company of Rangers was present at the Battles of Saratoga (they were batteau men).

Back to Amsbury. While there is no smoking gun in this instance to prove that Dr. Samuel Adams, loyalist was with William Amsbury, there is an abundance of circumstantial evidence. Dr. Sam left Arlington in 1776 and his presence was focused in New York and with his troops in Canada. We have a letter dated July 11, 1776 written by Dr. Sam from Pawlington, New York to his brother, Andrew, in Litchfield. Dr. Samuel Adams, loyalist spy, knew General Arthur St. Clair personally (having dined with him and General Anthony Wayne, and other high ranking military officers- as provided by Col. Jeduthan Baldwin). St. Clair handled Adams’s interrogation personally and that report was sent to General Philip Schuyler and then sent on to General George Washington. Adams was released because they knew him to “be a good fellow” and they thought he was a spy for the Americans. The families of Andrew Adams and Benjamin Tallmadge were very close (Andrew’s son married Benjamin’s granddaughter). Andrew Adams was a neighbor of General Oliver Wolcott. Washington used the Wolcott house in Litchfield as one of his headquarters during the revolution. It certainly makes sense that Dr. Samuel Adams could have been the one travelling with Amsbury from Montreal as Dr. Sam made that trip several times in splitting his time between Lake George and Montreal where his Company was based. Again, no proof but an abundance of circumstantial evidence.

I agree with you, Doug, in regards to your description of the course of events following the capture of Amsbury and Adams right up to the point that you say he was released because they knew him to “be a good fellow.”

When I first introduced Private James Adams as the travelling companion of Amsbury in March of 2014, I did not bother to carry the story beyond the point of his confinement at Ticonderoga following his initial capture. I did establish, however, that the Adams captured with Amsbury was an American soldier that had been captured at Sabbath Day Point earlier that spring based on statements made by both St. Clair and Col. Thomas Marshall, and that James was the only Sabbath Day Point prisoner with the Adams surname documented as having been among those that had actually been transported as prisoners to Canada.

Private James Adams had been enlisted in Capt. John Graham’s 2nd Company of the 1st New York Regiment on March 9, 1777 by Lieut. Nathaniel Henry. His name appears on the company muster roll of June 5, 1777 as having been captured on March 20th. Consequently, as he had enlisted for the war, he would not have been released after having been cleared of any involvement with Amsbury’s mission – he would have been returned to duty with his regiment.

A guard detail commanded by a Lieut. Wendell escorted Amsbury and Adams to Saratoga for further questioning by Gen. Schuyler after St. Clair’s interrogation, and Schuyler states that they arrived on June 15th. Satisfied that Adams was probably not a threat, Schuyler decided that he should be returned to duty and instructed his aide, Henry Livingston to have Adams assigned temporarily to the Saratoga garrison commanded by Captain Fink. Livingston’s letter, dated June 16th to Fink, is as follows:

“As Adams one of the prisoners brought to Saratoga Yesterday by Lieut Wendell was inlisted into our service previous to his being taken by the Enemy, and nothing very criminal appears against him, General Schuyler desires you will detain him to do Duty with your Garrison. You will however keep a strict watch that he does not make his escape, or do any mischief while under your Command. if you shou’d discern the least intention of that Kind have him closely confined immediately. William Amsbury the other prisoner you are to send down to Albany under Guard with Lieut Wendell who will deliver him to Lieut Colo Tupper the Officer commanding at that place.”( Schuyler Papers, New York Public Library; Livingston to Capt Fink, June 16th, 1777; # 1739).

Fink informed Captain Graham that Adams had returned to duty, and had been assigned by Schuyler to the Saratoga garrison. Two weeks later, the muster roll for Graham’s company dated June 29th no longer listed James Adams as captured on March 20th , but as returned to duty “on command at Saratoga.”

Based on the facts as presented, I don’t think that you can honestly deny that the evidence seems rather definitive in favor of James Adams being Amsbury’s companion .

Now back to Samuel Adams. The Samuel Adams you seem rather reluctant to recognize, Doug, is the Samuel Adams that held the Sabbath Day Point patent, not Dr. Samuel Adams of Arlington. The actual petition for this patent was written by my Irish immigrant on June 20th, 1764, and submitted for him by William Gilliland, the founder of Willsboro, on Aug. 7th of the same year. In that petition, Adams states that he had been residing on that land for 2 years, which means that he arrived at Lake George in 1762, or two years before Dr. Samuel Adams even left Connecticut for Arlington.

If you were to consult Antliff’s Loyalist Settlements, 1783-1789: New Evidence of Canadian Loyalist Claims, p. 110-111, you will find my Samuel Adam’s claim for financial compensation for the property mentioned and a brief description of his background which he was required to give under oath:

Montreal June 20, 1787

Evidence on the claim of Saml. Adams late of Lake George New York

Claimant — Sworn

He is a native of Ireland he came to America in 1754 and settled on Lake George in 1762 where he lived in 1775.

Says at no time did he ever join the Rebels in any respect

He joined the British Army in 1777 but returned to his own House in consequence the Rebels confined him to his own House – until Genl Burgoynes defeat when he came to Canada and has been in Canada residing near Montreal ever since

He resides at Point au Tremble near Montreal.

His Lands have not been sold and he therefore has made no Claim.

The Rebels in 1776 burnt a House he had at Sabath day point – because of his Loyalty – it cost him L40 Currency.

A New House at Lake George Burnt at the Retreat of the British Army by Order of Govr. Powell –

Values the House at L100

Furniture 10

12 Horses on his Farm taken by Indians L90

Three Cows killed L18.15

Crop Destroyed by the Troops 10

Aside from the description of the property, please note the fact that he was seeking L90 compensation for 12 horses taken from him by Indians, as this references the losses he suffered when captured by Samuel Mackay on March 19th, and establishes him as the proprietor of the inn at Sabbath Day Point. If you consult De Lorimier and Mackay’s accounts of the capture of Samuel Adams and his party, you will find that both mention that Adams was driving horses at the time of his capture. Baldwin’s Journal also states that he was on his way to Sabbath Day Point with horses at the time of his capture, though he states the number was 13 instead of 12.

Consequently, it seems that Samuel Adams the Irish immigrant did, indeed, exist and the evidence seems to strongly suggest that he, not Dr. Samuel Adams, resided on the Sabbath Day Point patent.