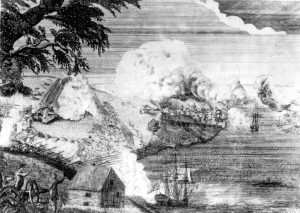

As the British surveyed the fortifications being built upon Breed’s Hill across the harbor from Boston proper, beside the farmers, shop keepers, tradesmen and aspiring soldiers, one must wonder if their focus stopped when they saw what must have appeared to them as an elderly man with the bearing that comes from martial experience directing the fortification efforts. What exactly that man looked like is unclear, as no image of him has been found, but Richard Gridley was a man of experience with siege work, having been involved in the capture of Fortress Louisbourg in 1745 as well as having served as a volunteer engineer during the French and Indian War under Amherst when the British again laid siege to Fortress Louisbourg in 1758. Richard Gridley is not a name often offered when reciting the founding fathers and the patriot heroes who served under George Washington. Gridley was key to the success of the patriots’ first real tests at Bunker Hill and the Siege of Boston.

Gridley was born in colonial Boston on 3 January 1710, the son of Richard and Rebecca Gridley. He was the youngest of twelve children.[1] He was apprenticed to a Boston merchant and married at age 20. His first wife, Hannah Deming, brought him between six and nine children. Richard was the first born on 12 July 1731. Hannah was born on 1 June 1732. The elder Hannah died sometime prior to 1751 when Gridley remarried Sarah Blake in Boston on 21 October 1751.[2]

While living in Boston, Gridley appears to have cultivated a friendship or become the protégé of John Henry Bastide, a British engineer officer sent to America to improve the harbor defenses throughout Nova Scotia and New England in 1740.[3] Bastide was assigned in 1743 to construct Fort William in Boston Harbor, a project occasionally credited to Gridley. When King George’s War (War of Austrian Succession) broke out with France, Gridley joined the Massachusetts provincial troops as the lieutenant colonel of Joseph Dwight’s militia regiment. Dwight’s regiment was organized to serve as artillerists. When Dwight was promoted to brigadier general, Gridley took command of the regiment itself. Gridley was then named chief bombardier during the siege of Fortress Louisbourg and performed some engineering functions as well.[4] General William Shirley, the governor of Massachusetts, was so impressed with Gridley’s service that when Shirley and William Pepperell were authorized to raise two “American” regiments for garrisoning Louisbourg, Gridley acquired a captain’s commission in Shirley’s 65th Regiment of Foot. However, his date of rank is given as 30 April 1746 not September 1745 as the original officers of the regiment were dated. It is unclear if that is a clerical error or if Gridley replaced another officer. Gridley was one of approximately two dozen Americans who were provided regular commissions. According to historian William Foote, Shirley and Pepperell were each allowed to appoint two of the captains, eleven of the lieutenants and four of the ensigns. Effectively, those commissions were to go to Americans; the other commissions were appointed by the King from among serving officers and those on half pay.[5]

Gridley remained at Louisbourg as part of its British garrison until the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle returned the fortress to the French. Returning the fortress to the French was particularly disliked by the Americans who had taken the post. They felt that the British government had betrayed their service. Both Shirley’s 65th Regiment of Foot, and Pepperell’s 66th Regiment of Foot were disbanded in May 1749, the officers all being placed on half pay. Gridley’s map, Plan of the City and Fortress Louisbourg was published in Boston in 1746 and in London in 1758.[6]

Gridley returned to civilian life in Boston. He appears to have become a member of the Masons in Boston about 1745. His older brother Jeremiah Gridley was also a Mason. Both men were actively involved in the Masonic fraternity for the rest of their lives. When the next war erupted between Britain and France in 1755, Gridley again was drawn to martial pursuits.[7]

Gridley was appointed colonel of his own regiment as part of Sir William Johnson’s expedition against Crown Point. Johnson left him in command at Ft. Edward, New York. Johnson wrote the following about Gridley, “if all the Officers of his Rank in the Army were equal to him I should have thought myself very happy in my Station.” The next year, Gridley was appointed as a provincial colonel as chief engineer and commander of artillery in John Winslow’s expedition to protect Maine from the advancing French. He was involved in constructing Fort Western, Fort Halifax and Fort William Henry in present day Maine during that period.[8]

In 1758, Gridley accompanied Amherst’s expedition against Louisbourg as a volunteer engineer under the command of Bastide, now a colonel and chief engineer. Gridley, though only a volunteer, took command of Colonel Nathaniel Meserve’s New Hampshire Company of carpenters and boatmen after Meserve died. The company built blockhouses and a wharf under the direction of Colonel Bastide.[9]

After Louisbourg fell, Gridley raised a similar company of carpenters and was given command of the provincial artillery under James Wolfe for the 1759 campaign against Quebec. According to secondary sources, Gridley was significantly involved in assisting Wolfe plan the attack on Quebec. Gridley also continued to be an active mason and was charged with setting up several field lodges while in Quebec.[10]

After Quebec fell, Gridley returned to civilian life. He requested permission to conduct seal and walrus fishing in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and appears to have done so with four of his sons. By 1765, Gridley’s fisheries were under his son’s control, who continued to press the British for a grant until 1777. Gridley did receive a land grant of 3,000 acres in New Hampshire in 1770 for his provincial service during the French and Indian War. Gridley returned to Boston and began a smelting operation by 1772 near Sharon, Massachusetts.[11] Gridley is mentioned in several sources as being the chief architect of Boston’s long wharf, but the wharf was originally constructed beginning in 1710. Gridley may have been involved in some type of repair project on the wharf which historians misconstrued.[12]

When the Massachusetts Provincial Congress needed someone to head the Massachusetts Train of Artillery, it appointed Gridley as its colonel on 19 May 1775. The train was taken into Congressional service as Gridley’s (later Knox’s) Regiment of Artillery. Gridley would remain the commander of the regiment until he was replaced by Henry Knox on 17 November 1775. It isn’t entirely clear if Gridley was appointed as the chief engineer of the army at the same time. Huntoon indicates that Gridley was appointed to that position on 23 April 1775 by the provincial congress.[13]

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress took another step on 23 June 1775 and promoted Gridley to Chief Engineer and Colonel of his regiment with the rank of major general. His regiment’s lieutenant colonels were to rank as colonels in the army and his majors as lieutenant colonels. The US Army Corps of Engineers’ records state that he turned down the major general’s commission as he had never “seen an army so overstocked with generals and so poorly provided with privates.” This may be true as he is routinely referred to as “Colonel” in contemporary sources and not general.[14]

One of the concerns with Gridley in command of the regiment wasn’t necessarily his blatant nepotism in filling the officer corps of the regiment, but that some of the officers he was appointing weren’t competent. His friend and former colleague William Burbeck was appointed first lieutenant colonel and Gridley’s son Scarborough Gridley was appointed as one of two majors for the regiment. Two other sons, Samuel and John, were appointed as a captain and a first lieutenant respectively as the regiment was built up. Scarborough’s conduct at Bunker Hill was so poor that he was tried by a court martial in September 1775 and dismissed from the service. Samuel had experience in the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Boston. He appears to have joined that unit in 1765 and is listed as the second sergeant in 1767. Samuel was also court martialed after Bunker Hill but was found not guilty. The pain caused by those who accused him forced him to resign in July 1775 and he didn’t serve further with the Continental Army.[15] John does appear to have served competently and remained an artillery officer throughout the war. He served with the 3rd Continental Artillery until 3 June 1783. He was promoted to captain lieutenant on 1 January 1777 and brevetted to captain on 30 September 1783.[16]

Gridley was wounded in the thigh at Bunker Hill and his personal courage was never in doubt. At one point he took personal command of Captain Trevett’s battery; the one part of his regiment that served honorably that day. Unfortunately, the majority of the artillery officers performed poorly and in some cases, criminally so, so that Gridley’s reputation was tarnished. According to Lieutenant Colonel David Mason, “I personally like – I even admire Colonel Gridley. He is a devoted patriot who has risked his life for our cause. Unfortunately, many of my men don’t like him. His sons have been court-martialed for cowardice and Gridley had appointed them above other more competent officers. Some officers blame the colonel for the misdeeds of his sons… and some for the outcome of the battle itself.” Of course, the British were not pleased with Gridley’s actions at Bunker Hill either and he was struck from the half pay list effective 28 July 1775.[17]

Even after the defeat at Bunker Hill, Gridley’s skills as an engineer were highly valued. Congress appointed him as colonel and chief of artillery on 20 September 1775. Washington wished to replace Gridley as the commander of the artillery regiment and did so by asking the Congress to appoint Henry Knox is his place on 17 November 1775. The public excuse given seems to have been Gridley’s advanced age and the time it took him to recover from his wound. Gridley however remained as the chief engineer of the army and in that role designed the fortifications on Dorchester Heights that eventually required the British to evacuate Boston in March 1776.[18]

When the Continental Army left Boston in the summer of 1776, Rufus Putnam was appointed as the new chief engineer and Gridley remained in the Boston area as colonel and engineer of the Eastern Department. He was chiefly responsible for overseeing the development of coastal fortifications along the eastern coast. He remained actively involved in the patriot cause until he retired on 1 January 1781 just shy of his 71st birthday.[19]

Besides his military service, Gridley’s forge at Stoughton produced the first howitzers and mortars for the Continental cause in 1776 and 1777. He remained in the Stoughton area until he died from blood poisoning that developed when he cut himself while trimming his dogwood bushes. He was originally buried near his house, but was reburied in the Canton (MA) Corner Cemetery in 1876 where a monument was erected in his honor.[20]

Richard Gridley is one of the overlooked contributors to the success of the American Revolution. He is remembered by the US Army Corps of Engineers as its first chief engineer and the father of the Army Corps of Engineers. He played significant roles in King George’s War, the French and Indian War and the Revolution and yet he remains nearly unknown.

[1] Daniel T. V. Huntoon, History of the Town of Canton, Norfolk County, Massachusetts (Cambridge, MA: Wilson and Son, 1893) v 1, 8, 151 – 163, v 2, 360-379; John Healy, “Richard Gridley,” Welcome to Historical Canton accessed at http://cantonmahistorical.pbworks.com/w/page/34431174/Richard%20Gridley. His older brother Jeremiah Gridley was a Harvard graduate and accomplished attorney in Boston.

[2] Stuart R. J. Sutherland, “Richard Gridley,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, v. 4, 2013 accessed at http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gridley_richard_4E.html; Brookline Historical Society, Publications of the Brookline Historical Society (Brookline, MA: The Historical Society, 1903) 12, enumerates six children. Huntoon and others state the union produced nine offspring, but do not name them.

[3] Bastide (ca 1700 – 1770) was the son of a French Huguenot officer. He commissioned as an ensign in 1711 in Hill’s Regiment and became a lieutenant in 1718. He was assigned as an engineer in the Channel Islands from 1726 to 1739. He was assigned to North America in 1740 and served at both British Sieges of Louisbourg. He eventually reached the rank of lieutenant general.

[4] Mark M. Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, 3d ed. (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 1994) 458.

[5] WO 25, Commission Books and WO 64, Manuscript Army Lists, The National Archives, Kew, England; William A. Foote, The American Units of the British Regular Army, 1664-1772, University of Texas at El Paso, 1959 [unpublished thesis], 159-164.

[6] Boatner, 458-9; WO 25, Commission Books; Nathaniel Philbrick, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution (New York: Viking, 2013) 172, states that Gridley’s half pay for life was in reward for his outstanding service at Louisbourg. That isn’t accurate. Gridley earn a regular commission based upon his performance. Half pay for life was a standard for all British officers reduced at the end of a war.

[7] Reginald V. Harris, “Freemasonry at the Two Sieges of Louisbourg,” The Papers of the Canadian Masonic Research Association, 1949-1976 (The Heritage Lodge No. 730, 1986) v 2, Paper 46.

[8] Boatner, 458-9; Barry M. Moody, “John Winslow,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, v. 4, 2013 accessed at http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/winslow_john_4E.html.

[9] Hugh Boscawen, The Capture of Louisbourg, 1758 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011) 122 & 326.

[10] James E. McNabney, Born in Bortherhood: Revelations about America’s Revolutionary Leaders (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2006) 41.

[11] Sutherland; US Army Corps of Engineers, Colonel Richard Gridley, First Chief Engineer: the Forgotten Soldier of the Battle of Bunker Hill. (n.p., May 1775) 2; The US Army Corps of Engineers states that Gridley was rewarded with a grant of the Magdelen Islands, but in fact the British government ultimately turned down his request.

[13] Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, April 1775 to December 1783 (Washington, DC: W. H. Lowdermick & Co., 1892); Huntoon, v.2, 360-379.

[14] Rank of the Officers in Colonel Gridley’s Regiment, 23 June 1775, Massachusetts Provincial Congress, v. 2:1436; US Army Corps of Engineers, 4.

7 Comments

Thank you for a well-researched and necessary article. As with all great events, historians’ continuing research uncovers stories like this that should be told. Your article is an example of why this website rocks.

It’s not hard to figure out why Gen. George Washington wanted to replace Col. Gridley with Henry Knox. The record of the commander’s meeting with Continental Congress delegates on 23 Oct 1775 includes this item: “Very unhappy Disputes prevail in the Regiment of Artillery—Col. Gridly is become very obnoxious to that Corps and the General is informed that he will prove the Destruction of the Regiment if continued therein.”

Washington had already alerted the Congress about how the Massachusetts government had promoted Gridley to major general but he had no Continental commission for the man and, it’s clear, didn’t want to promote him. Gridley’s alleged reluctance to become another general wasn’t involved.

A lot of the writing about Richard Gridley goes back to the articles of Daniel V. T. Huntoon, a hometown historian who chose not to acknowledge the evidence of Washington’s poor estimate of Gridley as a regimental commander. Huntoon’s errors all tended to increase Gridley’s importance.

More recent research by David Ingram shows that Capt. Samuel Gridley of the artillery regiment was not the colonel’s son but his nephew. The colonel had a son named Samuel, but British and American government records show that in 1775 he was still working on those fisheries in the North Atlantic.

James McNabney’s Born in Brotherhood (quoted a couple of times above) is not a reliable historical source. It provides no citation for the words from David Mason quoted above, and those words read like modern conversation, not eighteenth-century prose.

Mr. Bell, your comments about Washington’s dislike of Gridley seem evident in the article. However, your cite doesn’t clarify the issue. Was Washington jealous of Gridley who had much more real successful military experience than Washington? Washington’s letter also seems wrong in that Gridley turned down the appointment as a major general, so Washington seems to not have understood the actual standing of his artillery chief.

I think Washington’s words about “the Destruction of the Regiment” offer more solid evidence about why he wished to replace Gridley as head of the artillery regiment than what appears in the article. It’s possible that Washington was jealous of Gridley as an older man who had a regular British army rank and pension (Washington never gained that parity with the regular army), but making that case would require more evidence.

What’s the evidence that “Gridley turned down the appointment as a major general”? The U.S. Army Engineers publication offers no direct quote or citation. Meanwhile, we can read Washington’s August 1775 letter which makes clear that the issue of rank was still up in the air. If Gridley had declined Massachusetts’s promotion in June or July, the commander-in-chief would have reported that to the Congress.

Another interesting detail of Gridley’s Revolutionary War career not mentioned in this article is that the Massachusetts Committee of Safety records show that it summoned him on 21 April 1775—and Scarborough Gridley as well. That suggests Massachusetts’s Patritot political leaders had already consulted with the highly respected colonel and made arrangements for his service. It also appears that Col. Gridley had set two conditions. One was a high rank for his son, who had no experience to offer on his own. The other was that the province would recompense the colonel for the likely loss of his British army pension, and indeed the Provincial Congress voted to pay him £123 per year after its army disbanded.

I think it’s valuable to examine Richard Gridley and his military career. But it’s vital to get around the many unreliable secondary sources about him and take a clear-eyed look at primary sources like the Washington letters and Massachusetts Provincial Congress records.

“Gridley is mentioned in several sources as being the chief architect of Boston’s long wharf, but the wharf was originally constructed beginning in 1710. Gridley may have been involved in some type of repair project on the wharf which historians misconstrued.”

I seem to remember reading somewhere or seeing a map or illustration that indicated the Long Wharf had some artillery mounted on it. Maybe the design of that is what is being referenced.

Hi, I’m looking for informations on Richard or Samuel Gridley fisheries an walrus company

on the Magdalen Islands, St-Lawrence gulf, Canada, in the years 1770 ,at 1780.

The Newport Art Museum has a portrait of Richard Gridley, c 1745.

Oil on canvas painted by John Smybert.

It seems like your research is quite thorough but a shadow of a doubt was cast when you stated that no image of him has been found.