In April 1775, reports about the bloodshed at Lexington and Concord took five days to reach Philadelphia and nearly three weeks to reach Charleston, South Carolina. It wasn’t yet immortalized in history books as the start of the Revolutionary War. It was breaking news.[1]

In April 1775, reports about the bloodshed at Lexington and Concord took five days to reach Philadelphia and nearly three weeks to reach Charleston, South Carolina. It wasn’t yet immortalized in history books as the start of the Revolutionary War. It was breaking news.[1]

In July 1776, the Declaration of Independence took at least two weeks to be published in Boston and Williamsburg newspapers. It wasn’t yet a symbol of freedom, revered by multiple groups of people as a source of natural and legal rights. It was breaking news.[2]

When war erupted on April 19, 1775, thirty-eight weekly newspapers were being published on American soil from Portsmouth, New Hampshire to Savannah, Georgia. Colonial newspapers, the only mass media of the day, tended to be four pages and a tad smaller than modern tabloids with a menu of content that included advertising, local and foreign news, legal notices, essays and extracts of private correspondence. The average circulation was 600 – sometimes four or five times greater in the largest cities – with an amplified reach thanks to subscribers sharing among friends and family as well as reading their issues aloud in public places. Plus, an intercolonial exchange system among printers allowed newspapermen and women to reprint entire sections from other distant papers. As tensions turned to tragedy, the demand for domestic information skyrocketed, and rumors and intelligence from eyewitnesses and their confidants raced by horseback or ship to printers throughout America and abroad.[3]

Depending on the distance and terrain traveled, breaking news during the American Revolution was sometimes days or weeks old when it arrived at its destination, but it was often still the freshest information available. In some cases, printers benefited from big news breaking nearby. If the news coincided with the weekly newspaper print schedule, printing offices could rush to select sources and set type so hometown readers could learn early details on the same or next day as the actual event. Other times, if advertisements were abundant or news was significant, and supplies and labor were readily available, printers would issue an extra edition during the week.

In today’s internet age, proximity, print schedules and resources are no longer major factors in news reporting, but the dilemmas associated with breaking stories are the same as two centuries ago. Breaking news coverage of almost every modern tragedy – Benghazi, Syria, Navy Yard, Boston Marathon – is cluttered with questionable particulars and frequent clarifications or retractions that media attempt to sort out in the hours, days and sometimes weeks ahead. Similarly, the earliest American Revolution newspaper reports had the greatest potential for error. Printers frequently dealt with debatable sources and uncertain intelligence, often spreading coverage of the biggest stories across subsequent issues to reveal the latest layers of detail or correct mistakes from previous editions.

For instance, the chaos of a big breaking news story plagued Portsmouth printer Daniel Fowle, who published in his April 21 New-Hampshire Gazette one of the first detailed, albeit rumor and error heavy, accounts of the Battle of Lexington and Concord. While the early battle accounts he printed on the front page of his newspaper have been frequently cited by modern historians, Fowle’s lesser-known, back-page disclaimer is equally revealing about the moment:

The Publisher of this Paper Has been in such perpetual Confusion by the different and contrary Accounts of the late Bloody Scene, that all Mistakes must be overlook’d.

This not only demonstrates the printer’s struggle to make sense of the situation, but also indicates the importance Fowle placed on providing reliable information to his readers – a value shared by many of his fellow colonial printers at the time. Even though newspapers were the number one propaganda tool of the era, printers understood they still needed to publish news from credible sources in order to maintain a successful subscriber and advertiser base. Printers sometimes cautioned readers about unknown or unreliable sources when they hurried to piece together bits and pieces of oral, manuscript and printed intelligence to corroborate accounts for their readers.

Thanks to the gradual unraveling and reporting of practically every major event of the American Revolution, newspapers of the 1760s, 1770s and 1780s have been critically important to researchers and writers. They litter the footnotes of countless history books and, to me, serve as the photography of the era, providing vivid descriptions of people, debates and events long before cameras existed. Plus, newspapers are the “super primary source” because they contain the exclusive content that can only be found in newspapers of the period (advertisements, printed oral intelligence, news, etc.), as well as extracts of several other primary sources (letters, military reports, government communications, poetry and song lyrics, etc.).

As the only mass media in the 18th century, newspapers fueled colonial rebellion, sustained loyalty to the cause and aided in American victory. Many modern historians claim without newspapers there would have been no American Revolution, and the importance of newspapers is well documented by the Founding Fathers themselves. Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote to General Nathanael Greene on September 4, 1781, that a newspaper “in the present state of affairs would be equal to at least two regiments.” David Ramsay, who twice served as a delegate in the Continental Congress, wrote that “in establishing American independence, the pen and the press had merit equal to that of the sword.” George Washington had an insatiable appetite for newspapers and understood the immense power of the printed word, especially when it came to influencing public opinion.[4]

Long before Twitter, printers were taking advantage of pithy slogans and viral messaging like “Join or Die,” “Die or be Free,” and “Liberty or Death,” which adorned newspaper mastheads and peppered pages.[5]

Long before Twitter, printers were taking advantage of pithy slogans and viral messaging like “Join or Die,” “Die or be Free,” and “Liberty or Death,” which adorned newspaper mastheads and peppered pages.[5]

Long before Facebook, YouTube and Instagram, printers were making an impact with visual aids, such as the serpent and dragon cartoon, the woodcut engraving of Loyalist James Rivington hung in effigy, or a rudimentary map of the battlefield on Breed’s Hill on the front page of the Virginia Gazette.[6]

Long before the bias of left and right-leaning cable news channels, newspaper printers were pledging allegiances to Patriots or Loyalists by using propaganda tactics like name-calling, fear mongering, selective news printing and demonizing the enemy. Still, just as twenty-first-century viewers of MSNBC and FOX are aware of each station’s respective bias, eighteenth-century readers were well aware of each newspaper’s point of view.

More than 200 years before Twitter and CNN, newspapers were playing a pivotal role by informing audiences, organizing rebellions and keeping them interested. Propaganda as we know it today was first perfected and developed into an art form during America’s War for Independence. As a tribute to the role that newspapers played in making America, below are 10 breaking news reports from the American Revolution. Click each image to for a larger or full-page version.

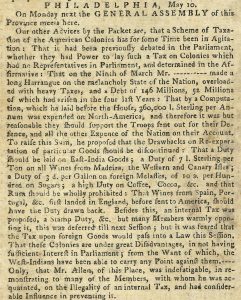

“A Scheme of Taxation”

Breaking news of taxation without representation from the Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), May 10, 1764

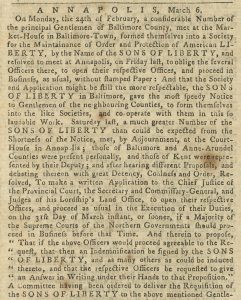

“for the Maintenance of Order and Protection of American LIBERTY”

Breaking news of the formation of the Sons of Liberty in Annapolis, MD, in the Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), March 20, 1766

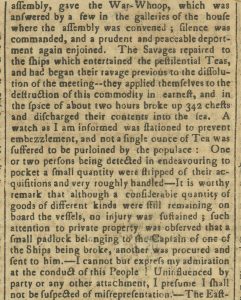

“The Savages repaired to the ships”

Breaking news of the Boston Tea Party in the Essex Gazette (Salem, MA), December 21, 1773

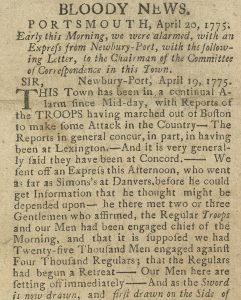

“BLOODY NEWS”

Breaking news of the Battle of Lexington and Concord in the New-Hampshire Gazette (Portsmouth, NH), April 21, 1775

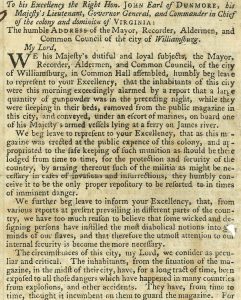

“exceedingly alarmed”

Breaking news of the Williamsburg gunpowder incident in the Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, Dixon and Hunter), April 22, 1775

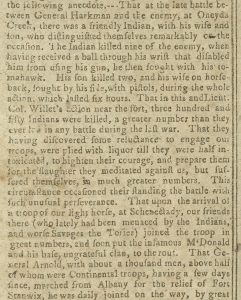

“three hundred and fifty Indians were killed”

Breaking news of the Battle of Oriskany (New York) in the Independent Chronicle (Boston), September 11, 1777

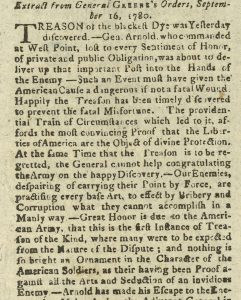

“Treason of the Blackest Dye”

Breaking news about Benedict Arnold’s treason in the Boston Gazette, October 16, 1780

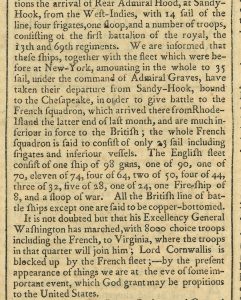

“we are on the eve of some important event”

Breaking news about the Siege of Yorktown in the Massachusetts Spy (Boston), September 13, 1781

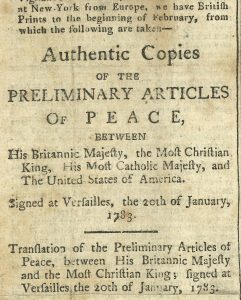

“Authentic Copies of the PRELIMINARY ARTICLES OF PEACE”

Breaking news about the terms of peace in the Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia), April 10, 1783

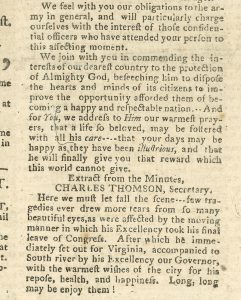

“few tragedies ever drew more tears”

Breaking news about Washington’s resignation as commander in the American Herald (Boston), January 19, 1784

[2] Clarence S. Brigham, Journals and Journeymen: A Contribution to the History of Early American Newspapers (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950), 58-59.

[3] Todd Andrlik, Reporting the Revolutionary War (Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, 2012). A compilation of academic references to early newspaper circulations can be found at http://raglinen.com/education/circulations/ Details from the following paragraphs are also supported by the newspaper reproductions featured in Reporting the Revolutionary War.

[4] David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, 2 vols. (1789). Bruce Chadwick, George Washington’s War (Naperville, Illinois; Sourcebooks, 2004).

8 Comments

Fascinating article! Thank you for the great examples of newspapers of the day. I would have like to have seen a news story on Charleston, SC: greatest Naval victory or one of the tea party protests. Thanks for this posting.

Thanks, Todd – Your articles are always the best!

Great article. It’s interesting how our exposure to news is accelerated by social media, online dailies, 24-hr cable news, etc. yet the same problems exist about accuracy and reliability. I think the process by which news spread in the 18th C. is a fascinating subject enough as your book so aptly covers. In 1775, what would going viral mean?

Good question, SPM. Many prominent documents, events and battles — such as the Declaration of Independence, Stamp Act riots, Lexington and Concord — were widely covered by numerous newspapers, which was the 18th century equivalent of going viral. Newspapers from the southern colonies are extremely rare with Georgia being considered a black hole by some historians. Still, big news from Georgia and the southern colonies often reached and was printed in New England newspapers. Note the issue of the Boston Gazette on page 19 of Reporting the Revolutionary War that contains news of the Savannah Sons of Liberty chapter that was originally printed in the Georgia Gazette.

Thanks, Pam and Cathi. Much appreciated!

Cathi, my book — Reporting the Revolutionary War — contains several pages of newspaper accounts about the Battle of Sullivan’s Island and the Siege of Charleston. The Boston Tea Party is referenced above with more in the book, too. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll love the book.

I will definitely be buying copies of this book. Just for everyone’s information, there were three tea parties in Charles Town, South Carolina. Charleston’s first “tea party” took place on December 3, 1773, thirteen days before the more famous one in Boston. They didn’t dump the tea but rather stole the tea and hid it in the Exchange Building. This building is a favorite place to visit and you can see where the tea was hidden. Thanks again for this great article. I look forward to the book.

Good stuff, Cathi. Charleston, New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other towns had what we might label a “tea party” in 1773 and 1774. Click here to read a detailed eyewitness account of the New York Tea Party from the May 2, 1774, Boston Evening-Post. Since the phrase “tea party” wasn’t used until a half century later, your comment raises an interesting question about defining such events. For instance, it’s my understanding that December 3 was the day the tea arrived in Charleston harbor and that the decision to store it in the basement of the Exchange Building wasn’t made until December 22. Or is the day the tea arrived in port the day the party started?

Very interesting article. Trying to get tea delivered was very difficult. The Mohawks took care of that delivery. I have seen the heavy, dense blocks of tea that was in use at that time. I wish the school textbooks were more detailed. It really gets me sometimes how there were some battles in the northern colonies then all of a sudden the surrender at Yorktown! No mention of the major fighting in South Carolina. More battles were fought and more blood was spilled in South Carolina than all of the other colonies put together. And Francis Marion was involved in half of those battles. Please google and check out the Francis Marion Symposium! Thanks!