The crevices and stony outcroppings of Devil’s Den, a 1,756-acre nature preserve in Weston and Redding, Connecticut, can provide shelter for hikers during an unexpected rainstorm. Or, as was the case for some women and children 236 years ago, the perfect place to hide during a British invasion.

It was shortly before sunset on April 25, 1777, when Major General William Tryon and his men sailed up Long Island Sound to the mouth of the Saugatuck River. They anchored off the coast of Fairfield and Norwalk, what is today Compo Beach in Westport, Connecticut. [1] In the space of six hours about 1,550 regular British troops and about 300 Loyalist militiamen unloaded supplies from 26 vessels.[2] The Loyalists were part of “Browne’s Provincial Corps” and many of them hailed from the Nutmeg State.

After unloading their supplies the force of 2,000 started a 23-mile march to its target: Danbury. It took them 36 hours along an inland route to reach their objective. Once in Danbury, a city that today has no pre-Revolutionary War era homes, the men burned homes, warehouses, farmhouses, storehouse, more than 1,500 tents and most importantly – ammunition stores.[3]

Stealth wasn’t on the side of the British. Spotters along the shore saw the fleet coming and riders were quickly dispatched to warn local militia leaders.

Civilians in Weston and Redding grew increasingly fearful when they heard news the British had landed and were poised to march near their towns. “Of course nearly every family had a musket in those days, but the safety of the women and children demanded almost the entire attention of the males of the community.”[4]

While those living along Connecticut’s coast frequently encountered the British, who often raided the coast in whaleboats and privateers, the people in these inland towns had no direct contact with British troops. Until now the war only reached the people through newspaper accounts and letters home or, more painfully upon the return of the wounded and the dead. Thus, the columns of marching British were a sight to behold: “…the appearance of the regular troops was worthy of note, as in uniform, equipment and discipline they represented the flower of the British army. Each horseman had upon his head a metallic cap, sword proof, surmounted by a cone from which a long chestnut plume fell to the shoulders…A red coat faced with white, an epaulette on each shoulder, buckskin breeches of a bright yellow, black knee boots, and spurs, completed the costume.”[5]

The British encountered little resistance along the way. The southwestern part of Connecticut had its share of Tories and Loyalists, some of whom helped lead Tryon, a native of Surrey, England, on his raid.[6]

Still, in spite of those who remained loyal to the British Crown, Weston and Redding town records show great support for the war. Most men fought in either the Continental Army or local militias.

In addition, towns such as Weston and Redding had Committees of Safety, groups of men who were to prevent anyone from giving aid and comfort to the British. Throughout the war resources were scarce for those on the home front. Most towns had to provide blankets, shoes, stockings, hunting shirts, and other clothing to Continental soldiers. Yet, many towns, such as Weston, were poor and had difficulty meeting the requirements.

According to local tradition, Devil’s Den got its name because of a boulder that bears a cloven-shaped imprint. Archaeological evidence shows humans used the area for hunting as many as 5,000 years ago. By the time of the Revolution local people used the area to fish, hunt and trap.

On the morning of April 26, the residents of Weston and Redding scrambled to hide their money, silver and other valuables. The Red Coats were known to plunder public and private property. As such, there was grave concern about ensuring the women and children were safe.[7] Choices had to be made. They could stand their ground and hope the British would leave them alone. They could try and stay ahead of the 2,000 strong column coming their way. Or, they could retreat to the safety of the rocky wilderness known as Devil’s Den. Many chose the latter knowing the British wouldn’t think twice of capturing young men and imprisoning them on their notorious prison ships anchored in Long Island Sound. The women also feared being raped.[8] And so despite the stormy weather, they stayed there until the evening of April 27.

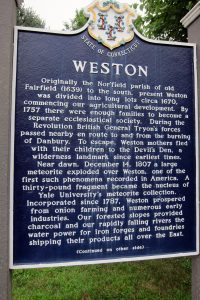

Meanwhile, the Patriots were unable to reach Danbury in time to prevent the destruction of supplies and homes. Instead 700 Continental Army troops, under the leadership of Gen. David Wooster and Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold, and irregular militia fought the British as they headed south through Ridgefield back to their boats. In the ensuing years Westonites started a charcoal making business in Devil’s Den; the men sealed burning cordwood in mounds for up to a month or more. Today, little more than a plaque outside the Weston Town Hall commemorates the local’s brush with the British.

[1] Ives, J. Moss. “A Connecticut Battlefield in the American Revolution: Danbury-Captured And Burned By the British In 1777-Village Sacked By General Tryon-Fascinating Story of a Frontier Town in the Pioneer Days of the Indian Camp Pahquioque.” The Connecticut Magazine. Vol. 7, No. 5, 1902-1903. Pp. 421-450.

[2] Campaigns of the American Revolution (An Atlas of Manuscript Maps)”, D. Marshall & H. Peckham, University of Michigan Press, at Ann Arbor Mich., 1976, Page 40

[5] As quoted in Burr, William, Hanford. “Invasion of Connecticut By the British” The Connecticut Magazine. Vol. 10, 1906. pp. 139-152.

2 Comments

This kind of article colors in spaces in the War’s story that just wouldn’t make it into the history books. Thank you, Cathryn. The British may have passed through Weston and Redding unmolested but Wooster (KIA at Ridgefield)and that pesky Arnold (wounded) stung them enough that they didn’t return. A cannon ball is still embedded in the wall of Keeler Tavern. Ridgefield’s worth a visit.

Hi Steven,

I’m so glad you liked the article. It was a lot of fun to write. I love Ridgefield, and you are right – it is a great place to visit!