“No Tax on Tea! A Colonial Tea Debate”[1]

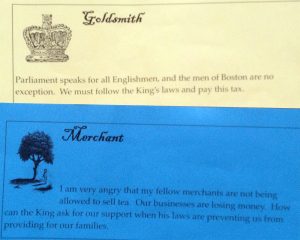

On Friday July 5, I returned to the Old South Meeting House for the “No Tax on Tea! A Colonial Tea Debate” program. Unlike “Whispers of Revolution: Plotting the Boston Tea Party,” this event invited audience members to “[assume] the role of a Patriot or Loyalist to debate the tax on tea!” A Meeting House docent handed each visitor a blue or yellow piece of paper. The slips contained the name and occupation of a colonial Bostonian and their position on the Tea Act. Blue papers described Patriot positions, yellow pieces Loyalist positions.

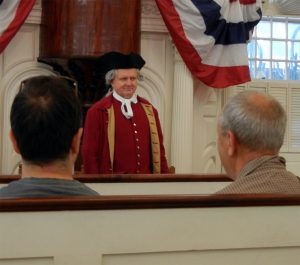

A museum educator began the program by setting the scene. On December 16, 1773, Patriots and Loyalists gathered at the Old South Meeting House to debate whether they should unload the cargoes of the three tea ships anchored in Boston Harbor or send them back to England fully loaded. The assembled colonists chose Samuel Savage of Weston, Massachusetts to moderate the meeting. A re-enactor playing Savage ascended the pulpit stairs.

Savage called the meeting to order. A Loyalist spoke first: “I am a loyalist. I believe we are all English citizens…[and that] we should pay taxes to our government.” The Loyalist asserted that tax revenue paid for the colonies’ military protection and governance. These beneficial services provided colonial society with stability. The Loyalist concluded, “We should be respectful of our government” by paying the taxes it levies. Raucous cries of “Huzzah!” and “Fie!” filled the meetinghouse.[2]

A Patriot countered, “We did not decide on this tax in Parliament because we do not have a representative. We should not let the tea land in our harbor and we should not be buying it! We should continue our boycott.” Once again, cries of “Huzzah!” and “Fie!” echoed throughout the chamber.

Kids, parents, 20-somethings, older people, Americans, and foreigners alike participated in the debate with equal vigor. About sixty people attended the program. Most participants read the provided scripts. The assigned lines made for an interesting debate because it allowed for the expression of moderate as well as radical viewpoints. One woman argued that she did not like the tea tax, but reasoned that as a port city, Boston needed trade to stay alive. Therefore, she wanted to land the tea and pay the tax to keep the port open. A man offered a different moderate opinion: the colonists should pay the tea tax when Parliament showed the colonists how it planned to spend its revenue.

Several participants, adults and children, embraced their assigned roles so thoroughly that they spoke extemporaneously. Their spontaneity demonstrated a careful consideration of their assumed persona’s point-of-view, as did participants’ use of the pronouns “us” and “them.” One man got so caught up in his Patriot role that he forgot his periodization. The man blamed the “British” for the Boston Massacre, forgetting that the colonists identified as Britons in 1773.

Savage called for a vote after nearly twenty minutes of debate. Our present-day re-enactment did not depart from history. The gathering decided not to pay the tax.

After the program, I approached Tegan Kehoe, Museum Educator at the Old South Meeting House. At the start of the program, Kehoe’s colleague mentioned that Meeting House staff use a similar program to “No Tax on Tea!” to teach school groups about the Revolution and the Tea Party.[3] I wanted to know if the kids who read their scripts line-for-line understood and grappled with the meaning of what they read in a calmer, classroom setting.

Kehoe explained, “It depends on the program and on the kids.” For students the tea debate represents the “culmination of a lot of preparation” so the “kids are definitely thinking about it [what the arguments mean].” Meeting House educators work with teachers to “plant the seeds” of the different political stances in the students’ heads to help ensure their consideration of them. To this end, Old South Meeting House educators use forty different scripts, which comprise the viewpoints of twenty Patriots and twenty Loyalists. Like the public-program scripts, the school-program scripts contain the name of a colonist, their occupation, and their political position. Since the educators have more time to work with school groups, their scripts also include why the assigned colonist held the opinion they did. This information provides fodder for longer conversations about revolutionary-period politics.

Old South Meeting House educators conduct different versions of the same program with different age groups. The third-grade program establishes a foundation of basic information such as how do you read, pronounce, and define the word “Parliament.” In contrast, when Meeting House educators work with fifth-grade, eighth-grade, and adult groups they field a lot of “really fantastic in-depth questions” such as whether the Revolution was about principles, economics, or reform and “whether conflict was inevitable.” These questions allow Meeting House staff to talk about the variations in revolutionary-period political opinion.

Old South Meeting House educators help students and visitors grapple with the different political philosophies of the American Revolution through participatory programs. The adults and children I watched embraced their assigned Patriot and Loyalist roles with enthusiasm. Kehoe confirmed the same response among private-program participants. However, it has taken years of tweaking for the Meeting House educators to develop the balanced and well-received program I witnessed.

Via an e-mail exchange, Robin DeBlosi, Director of Marketing and Special Events for the Old South Meeting House explained, “Until a few years ago, we used to allow folks to choose their side in the No Tax on Tea debate, but we found too few visitors chose to be Loyalists.” When educators asked visitors to play Loyalists, “People would actively shove the Loyalist cards back to us, saying they had to play Patriots!” Combined with an imbalanced debate, these reactions prompted the Meeting House educators to assign roles. Even this change has not eliminated some visitors’ distaste for Loyalists. DeBlosi stated, “we still get folks who react immediately to their Patriot or Loyalist card, even if they have not read its contents.”

DeBlosi’s remarks highlight that some Americans still understand the Revolution as a story of “winners and losers.” The Patriots won, the Loyalists lost, and no one wants to play the role of a loser. However, the evidence from the “Whispers of Revolution” and “No Tax on Tea!” programs also indicate a changing landscape in United States history education. In recent years, many historians, historic organizations, and history teachers have reintroduced the variations and nuances of political opinion and loyalty choices into their narratives of the American Revolution. These efforts strive to improve American understanding of the Revolution. Programs like “No Tax on Tea!” allow Americans to interact with Loyalist viewpoints and derive a different and more nuanced understanding of the Revolution.

My positive experiences at the Old South Meeting House left me with a desire to see how other organizations integrate and interpret Loyalists into their narratives of the American Revolution. So after my conversation with Kehoe, I walked to nearby King’s Chapel to see their Loyalist-centered program: “Tory Stories.”

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...