The historical debate concerning the Loyalists in the Revolutionary South has generally focused on matters such as the Loyalists’ numbers and motivations. While these are issues deserve study, one aspect of the Loyalists’ role in the southern campaign has received far less attention: that of leadership. The British government’s “Southern Strategy” depended to a great degree on the army’s ability to mobilize southern Loyalists into an effective fighting force. However, no matter how numerous or motivated the southern Loyalists were, they could not be effective without good leadership. As experience had shown both sides in the Revolution on numerous occasions before the British began operations in the South, a small but well led unit was capable of defeating a much larger force that lacked effective leadership. Unfortunately for the British, their inability to find effective leaders to command southern Loyalists seriously impaired their plan to hold captured territory with local forces while advancing their conquests northward.

Loyalist leaders in the South can be placed in three categories. The first consisted of British officers who commanded Loyalist troops in provincial units. The second comprised northern Loyalists who led provincial units recruited in the North, and the third was made up of southern Loyalists who commanded locally raised provincial or militia forces. Within each of these categories, the quality of leadership ranged from outstanding to incompetent, although in general regular British officers provided the best leadership and southern Loyalists the worst.

British officers who led Loyalists in the field included Lieutenant Colonel Francis, Lord Rawdon, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, and Major Patrick Ferguson. Rawdon, who exercised field command of the British army in South Carolina from January to June 1781, proved remarkably adept at utilizing British regulars in combination with northern and southern provincial troops in a variety of conditions ranging from set-piece battles such as Hobkirk’s Hill to antipartisan operations. Tarleton and Ferguson commanded smaller units of vastly different composition, and with equally varying results.

Tarleton’s British Legion, a mixed force of infantry and dragoons, was organized during the summer of 1778 from Loyalist units recruited in the Philadelphia and New York areas. The amalgamation of different small units, including the Caledonian Volunteers, Philadelphia Light Dragoons, and individual recruits, melded together well under Tarleton’s leadership. During the British operations against Charleston in 1780, the Legion’s soldiers proved their mettle by smashing the Continental cavalry at actions like that at Lenud’s Ferry (May 5), despite the fact that the Americans were veterans under capable officers such as William Washington. The Legion’s success was instrumental in isolating the defenders of Charleston, who surrendered a week later.[i]

Tarleton and the Legion’s next action was an impressive but controversial feat. Ordered by Lieutenant General Charles, Earl Cornwallis, to destroy if possible the last remaining Continental force in South Carolina, Tarleton set off in pursuit of Colonel Abraham Buford’s regiment of Virginia infantry. After traversing a distance of 105 miles in 54 hours through rain and stifling heat, Tarleton caught Buford just south of the North Carolina border, near the Waxhaws settlement. Despite his troops’ exhaustion and facing a larger force, Tarleton crushed Buford’s regiment. The victory was so one-sided that many Americans pronounced the affair a massacre.[ii]

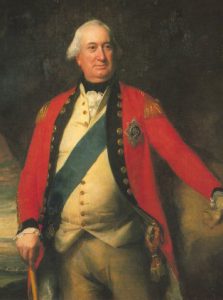

Source: U.S. National Guard

The British Legion went on to earn further laurels at the Battle of Camden (August 16, 1780), where its charge struck the decisive blow against American forces. That, however, was the pinnacle of the unit’s success. Unable to achieve a clear victory over American partisans, the Legion cavalry performed poorly at the Battle of the Cowpens on January 17, 1781, where the mounted troops ignored Tarleton’s order to charge and instead fled the field. The battle cost the Legion cavalry and its commander their reputations, and afterward neither ever performed as well as they had done earlier.[iii] Clearly Tarleton’s leadership, although outstanding throughout the early months of the southern campaign, was not sufficient to bring his dragoons into action under the adverse conditions they faced at Cowpens, or to completely restore their lost self-confidence.

If Tarleton created an effective Loyalist force that declined in performance over time, Ferguson faced a more difficult task at the outset, having poorer human material to work with and less time to organize and prepare his men before encountering his foes. Before departing Charleston to return to New York, General Sir Henry Clinton appointed Ferguson Inspector of Militia, giving the Scottish officer responsibility for turning the South Carolina Loyalists into an effective militia. As historian Paul H. Smith noted, Ferguson’s task required “the greatest attention to a multitude of details. The area involved was immense, the problems staggering,” particularly the shortage of qualified officers for the local units, “and the time limited.”[iv] Cornwallis noted an additional problem: the demoralizing effects of five years of Whig persecution. “The severity of the Rebel government has so terrified and totally subdued the minds of the people, that it is very difficult to rouse them to any exertions,” the earl noted.[v]

Since the Whigs already had a militia organization in place, with officers and units, around which persistent men could and did build the core of partisan resistance, Ferguson had to create a Loyalist militia from scratch, a task that needed to be approached with much urgency before the Americans could recover from the shock of Charleston’s surrender. Cornwallis, despite his awareness of the problems Ferguson faced, threw another obstacle into the path of his militia commander. Deciding that Clinton’s militia plan was inadequate, Cornwallis decided to draw up a plan of his own and on June 2 ordered Ferguson “to take no steps whatsoever in the militia business” until the earl issued further orders. The delay cost Ferguson nearly a month of valuable time that could have been spent vetting, organizing, and training the Loyalist militia.[vi]

By late July, Ferguson reported that the militia in Ninety Six District was “Daily gaining confidence & Discipline.”[vii] When the earl complained in August that militia units east of Broad River, where Ferguson had spent little time, had performed poorly against Whig partisans, Ferguson reminded him that those units “were form’d in a hurry, without the assistance of any officers of the Army to establish order & Discipline, [and] employ’d immediately on Service.” Thus, it was “to be expected that a Mungrill Mob without any regularity or even organization … without officers, without any previous preparation employd against the Enemy, would bring the name of Militia into discredit.”[viii]

Ferguson continued to make strides with the militia, but any hope of making South Carolina Loyalist militia units into an effective fighting force died in October with Ferguson at Kings Mountain. Many Loyalists believed that had Ferguson survived, he would indeed have succeeded in turning the militia into a creditable force. “Had Major Fergusson lived, the Militia would have been completely formed,” asserted Colonel Robert Gray, an officer of the South Carolina Loyalist militia who was highly regarded by Cornwallis and other British officers. “He [Ferguson] possessed all the talents & ambition necessary to accomplish that purpose … the want of a man of his genius was soon severely felt.”[ix]

One of the most effective officers who commanded a provincial unit but worked closely with the Loyalist militia was John Harris Cruger of New York. Cruger had no military experience before the Revolution; he had served on New York’s provincial council, as mayor of New York City, and was a successful businessman. Forced to flee his home in June 1776, Cruger escaped to Long Island, where he joined General William Howe’s army in August. A month later he was commissioned lieutenant colonel commanding the 1st Battalion of De Lancey’s Brigade. Sent to the South in 1778, he participated in the British capture of Savannah that December, served in the 1779 Siege of Savannah, and, after the fall of Charleston in 1780, was assigned to command the British post at Ninety Six.[x]

At Ninety Six, Cruger demonstrated excellent skills as a commander. In September 1780, learning that the Whigs had besieged Augusta, Georgia, Cruger marched to the relief of that post on his own initiative, then scoured the countryside to clear it of rebels. In May and June of 1781 he withstood Continental Major General Nathanael Greene’s siege of Ninety Six until Rawdon arrived to relieve him. He then led a column of provincial troops, militia, and civilian refugees through hostile territory, without loss, to reunite with Rawdon in the South Carolina lowcountry. Cruger’s biggest and least known achievement, however, occurred at the Battle of Eutaw Springs on September 8, 1781. When Greene appeared without warning before Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Stewart’s British army that morning, Stewart hastily deployed his troops for battle. In a virtually unprecedented move, Stewart assigned Cruger to command the army’s first line. Once Greene had deployed and Stewart saw that the American line extended well past the British left flank, Stewart ordered his reserve infantry into line, thus giving Cruger command of all of the army’s infantry, British and provincial. Rarely if ever had a British officer entrusted a provincial counterpart with such responsibility. Cruger proved worthy of the assignment, fighting Greene’s larger force to a standstill and even mounting a successful counterattack before American reserves put the British to flight. Even then, Cruger and Stewart rallied the troops, halted the American advance, and eventually launched a successful counterattack that drove Greene from the field. Afterwards, rumors circulated among both British officers and Loyalist civilians in Charleston that Cruger had been the army’s actual commander throughout the battle, which, true or not, testified to the esteem Cruger’s performance had earned.[xi]

The third category of Loyalist officers, those from the South who led local troops, includes commanders such as Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Brown, Colonel Robert Ballingall, and William Cunningham. Of these, Brown is by far the best known. Escaping to St. Augustine in British East Florida after the Whigs dispersed South Carolina’s Loyalists in November and December 1775, Brown’s aggressive nature attracted the attention of the like-minded governor of the province, Patrick Tonyn. Tonyn appointed Brown to command the King’s Florida Rangers, a battalion of Loyalist refugees. Brown proved an excellent leader in both partisan warfare and conventional operations, helping to thwart three American invasions of East Florida, raiding into southern Georgia, and later twice leading a stalwart defense of Augusta, successfully in September 1780 when Cruger came to his relief, and unsuccessfully in May-June 1781.[xii]

Robert Ballingall, in contrast, remains virtually unknown. Until 1779, Ballingall had managed to lie low and avoid attracting the Whigs’ attention. When the British raided into South Carolina that spring, Ballingall joined the king’s troops in May, but was captured a few weeks later and imprisoned. Released in October on account of ill health, he returned to service after the fall of Charleston in 1780, and was commissioned colonel of the Colleton County regiment of Loyalist militia. Cornwallis later enlarged Ballingall’s command to encompass most of the area south and west of Charleston. Despite poor equipment – in December Ballingall complained of the muskets and powder issued to his men “being very bad” – Ballingall’s was one of the few militia regiments that British officers considered reliable, and in fact held it up as a model unit. In April 1781, when Whig partisans under Colonel William Harden raided successfully in the vicinity of Dorchester, capturing forts and militiamen, Ballingall hurried to the scene and drove off the rebels. When he and his most committed followers were forced to seek refuge in Charleston later in the year, vengeful Whigs plundered his plantation before the state government confiscated it. Cornwallis, who had little positive to say about the Loyalist militia or its officers, later lauded Ballingall for his success “in raising & training the Militia,” while General Alexander Leslie praised Ballingall’s “honor, Integrity, and good sense.”[xiii]

In the waning months of the southern campaign, when diehard Loyalists resorted to partisan warfare against the Whigs, William Cunningham showed evidence of strong leadership as an irregular, in the process arousing the rebels’ ire and earning the nickname “Bloody Bill.” Cunningham first drew attention in July 1781, when he commanded a party of raiders and drew the attention of Brigadier General Andrew Pickens, who had to dispatch some of his men to check Cunningham. Eventually Cunningham joined other Loyalist refugees in Charleston. Five hundred Loyalists made a foray in November against General Thomas Sumter’s state troops, and when the force withdrew to Charleston, Cunningham separated from it and led a detachment of nearly one hundred men into the backcountry. Cunningham’s raiders defeated Whig militia in several skirmishes, burned mills, houses, and crops, and executed several rebel prisoners believed to have committed atrocities against Loyalists. The force returned to Charleston in December, beating some of Sumter’s soldiers who tried to stop them.[xiv]

Altogether, the officers discussed above provided solid and in some cases excellent leadership in the southern campaign. Faced with myriad difficulties, they organized, trained, and commanded both provincial troops and militia successfully in varied operations. Yet, there were never enough officers of their caliber to prepare and lead the South Carolina Loyalists in a way to develop consistently reliable fighting units across the state, and thus secure it from Whig partisans. In addition to the lack of capable officers, the Loyalists also lacked adequate arms and ammunition and, perhaps most important of all, time to develop the military skills and confidence necessary to become reliable soldiers. If, in the end, Cornwallis and most British regular army officers found the Loyalist militia lacking in these qualities, it was a sentiment that George Washington and a majority of his Continental officers shared in regard to the Whig militia.

[i] Carl P. Borick, A Gallant Defense: The Siege of Charleston, 1780 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003), 193-194.

[ii] Jim Piecuch, “The Blood Be Upon Your Head”: Tarleton and the Myth of Buford’s Massacre (Camden, SC: Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution Press, 2010), 16, 23-40.

[iii] Cornwallis to Lord George Germain, Aug. 21, 1780, Cornwallis Papers; Lawrence E. Babits, “A Devil of a Whipping”: The Battle of Cowpens (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 127-129.

[iv] Paul H. Smith, Loyalists and Redcoats: A Study in British Revolutionary Policy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964), 137.

[v] Cornwallis to Henry Clinton, Aug. 29, 1780, Cornwallis Papers, microfilm, David Library of the American Revolution, Washington Crossing, PA.

[ix] Robert Gray, “Colonel Robert Gray’s Observations on the War in Carolina,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, 11:143.

[x] Memorial of John Harris Cruger, February 9, 1784, Audit Office Papers, Class 12, Vol. 20, Folios 142-145.

[xi] Cruger, Memorial; Alexander Stewart to Cornwallis, Sept. 9, 1781, Cornwallis Papers; Royal South Carolina Gazette.

[xii] Edward J. Cashin, The King’s Ranger: Thomas Brown and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier (New York: Fordham University Press, 1999).

[xiii] Memorial of Robert Ballingall, March 13, 1786, and attached affidavits of Cornwallis, March 14, 1786, and Alexander Leslie, January 30, 1784, Misc. Mss., New York State Library, Albany; Major C. Fraser to Peter Traille, Dec. 30, 1780, George Wray Papers, Vol. 5, William L. Clements Library; Nisbet Balfour to Cornwallis, Nov. 5, 1780, Cornwallis Papers; Balfour to Archibald McArthur, April 10, 1781, Alexander Leslie Letterbook, microfilm, SC Dept. of Archives and History, Columbia.

[xiv] Andrew Pickens to Nathanael Greene, July 19, 1781, in Richard K. Showman, et al, editors, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 13 Vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1976-2005), 9:49; Thomas Sumter to Greene, Nov. 14 and 23, 1781, Papers of Greene, 9:575, 615; Sumter to Greene, Dec. 7 and 9, 1781, Papers of Greene, 10:15, 24; LeRoy Hammond to Green, Dec. 2, 1781, Papers of Greene, 9:651.

Recent Articles

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

Recent Comments

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

It seems there is no way to know the details of the...