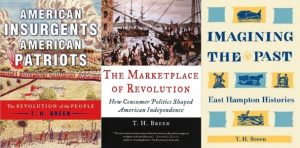

I recently asked our readers via Facebook who they’d most like to see interviewed next and T.H. Breen was among the handful of historians named (hat tip to Matthew Kroelinger). Breen is the William Smith Mason Professor of American History at Northwestern University and a specialist on the American revolution. He is the author of several books and more than 60 articles. In 2010, he released his latest book, American Insurgents, American Patriots. Breen won the Colonial War Society Prize for the best book on the American Revolution for Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (2005). Breen currently lives in Greensboro, Vermont, and recently took the time to answer a few questions about past and future works, recommended reading and time travel.

1 // American Insurgents, American Patriots reminds us that revolutions are violent events. Do you think there was a greater strategy behind most of the violence, or was it primarily raw emotion and vengeance?

The point of American Insurgents was that revolutions demand extreme personal sacrifice. They put ordinary people in harm’s way. The book was written to correct the notion that the American Revolution—unlike other revolutions that have changed the world—could be explained simply through an examination of political ideas. Of course, the men who risked their lives in battle or served on committees of safety could explain to themselves why they were resisting British oppression. The language of popular protest owed a lot to evangelical religion.

But to explain the Revolution as an ideological moment—as the play of abstraction notions about virtue and power–fails to address persuasively key questions about popular mobilization and structures of protest, about coercion and commitment, about communication of resistance across the divides of class and space, and about the ability to maintain revolutionary fervor over eight long years in which the prospects for success must have seemed remote. It should come as no surprise that the American Revolution—again, like other revolutions—involved violence. That fact should not be disturbing. Dissenters were treated as enemies.

Some historians may wish that our revolution had been less like the English or the French Revolutions—in other words, less violent—but then, if independence from Great Britain and the overthrow of the structures of aristocratic society had involved no more than a discussion of political ideas, Americans would still be part of the British Empire.

2 // In Marketplace of Revolution, we learn about the role of consumerism in fueling the American Revolution. In American Insurgents, you underscore the power of newspapers in igniting rebellion and sustaining insurgency. Merging consumerism and newspapers, what do you think about newspaper advertisements of the era (which often comprised more than half an issue) and what can they tell us about the Revolution?

In Marketplace of Revolution I attempted to re-affirm the central role of the the ordinary people in the organization of effective resistance to British policies. I was greatly influenced by the innovative work of the economic historian Jan deVries, who developed insights into an “industrious revolution” that preceded the industrial revolution. I also greatly profited from the work of Albert Hirschman, Carole Shammas, John Brewer, and Neil Mckendrick. They demonstrated that people of modest means in England, Holland, and British North America were able by the 1740s to obtain a wide range of manufactured goods that transformed their material lives. Consumer desire radically altered work routines within farm families.

Newspapers advertised the rich diversity of imported items; they promoted consumer desire. What I attempted to do in Marketplace was to show how this new, exciting exchange of goods suggested to the Americans a boldly innovative form of political protest. By interrupting the flow of goods within an imperial market they discovered that they could put pressure on policy makers in London. Goods in themselves were not political, but in this unprecedented social and economic context they became so. They became visible personal symbols of political oppression.

I believe that the ordinary Americans who supported these protests—men as well as women—should receive credit for seeing that consumer activities could become a powerful tool for political resistance. The use of boycotts to achieve political ends—a totally new strategy for mass mobilization—worked within a colonial framework in which the consumers were dependent on the imperial power for the goods that promised pleasure and fulfillment. The manufactures that the Americans wanted were British manufactures, and so, it made sense for colonists to define consumer goods as the source of their political dependence. Gandhi exploited the same link in his effort to advance the cause of Indian independence. He argued that as long as his people depended on British imports—chiefly manufactured cloth—they could never be politically free.

3 // Your Wikipedia page says your next project is a book for Simon & Schuster on George Washington. When can we expect it and what else can you tell us about this project?

In a book tentatively entitled Journey to a Nation: How George Washington and the American People Transformed Our Political Culture, I recreate a series of tours that Washington organized during his first years in office. He traveled thousands of miles, occasionally at the risk of serious accident, visiting scores of American communities from New Hampshire to Georgia. His decision to take the government to the people was extraordinary. He deserves as much credit as Hamilton and Madison for making the new republican system work. Washington’s primary goal was to strengthen the emotional bonds of union. He realized that for most Americans in 1789 the Constitution was an abstract agreement. Their loyalties were to the states. The power and promise of the new federal government had not yet touched the lives of ordinary men and women. The journey involved a masterful presentation of presidency. Washington understood theatrical elements of political culture. He had to learn how to act like a president, and although he had strong ideas on this subject, the American people he encountered on the road had equally strong notions about how the president should perform his office. The book explores the goals of the trip, the parades and festivals organized in Washington’s honor, the role of women in politics out-of-doors, and the terms of address that people used as they struggled to define executive office within a republican government for which there was no clear precedent.

4 // What other T. H. Breen projects are in the pipeline?

I am beginning a new book on the Revolution entitled The Revolutionary Origins of American Civil Society: Law, Toleration and the Language of Rights. Together with Professor Patrick Griffin of Notre Dame, I plan to organize a major conference on these themes at the Huntington Library in the spring of 2015. These projects will once again address the question: what exactly was revolutionary about the American Revolution.

5 // How did your interest in the American Revolution originate?

In so much as one can fully understand such decisions, I trace my interest in the American Revolution and to Colonial America (after all, my first three books deal with the 17th century) to a brilliant teacher and to the political society in which I came of age. The man was Edmund Morgan, a person who persuaded me that John Winthrop and his fellow Puritan magistrates were more interesting than were the Southern Populists I had originally intended to study when I entered graduate school. Morgan’s gentle insistence on the importance of good writing—his conviction that history is the story of men and women trying as best they can to understand the use and misuse of power—persuaded me to explore how people in local communities gave meaning to a larger world. They tried to shape their lives—to take control of events—but they could only do so within broader economic and political constraints. For me, the goal of the historian was to comprehend the contingencies of daily life, the sources of resistance and accommodation, the tensions between leaders and followers, for it was these conversations that made and destroyed empires. I was also a child of the late 1960s. I participated in the civil rights movement and the protests against the War in Vietnam. I became intensely aware then of how grievances against authority can yield resistance, how resistance can fail without effective mobilization, and how personal and local concerns blended with ideological imperatives to sustain a movement that demanded greater equality and freedom. These questions drew me back to the American Revolutionaries.

6 // What historians have most influenced your work?

Edmund Morgan, J.H. Hexter, John Blum, Quentin Skinner, Peter Laslett, Albert Hirschman, Clifford Geertz, Alan Ryan, and Peter Brown

7 // Which of your books is most personally satisfying and why?

7 // Which of your books is most personally satisfying and why?

Readers generally praised Marketplace of Revolution, which, no doubt, suggested a new way to look at the coming of the Revolution. American Insurgents raised unsettling questions about the character of popular mobilization before independence. But the most enjoyable book for me was Imagining the Past, a work that one reviewer condescendingly described simply as a study of a whaling community, but which in fact was a long reflection on post-modern narrative.

8 // Which new (since 2007) or soon-to-be-published books about the American Revolution are most intriguing to you? Why?

Patrick Griffin’s American Revolution, a well-informed and professional synthesis of the subject, impressed me. It is hard to say much in favor of all the recent “founding father” studies that rehearse what we already knew.

9 // What books – other than your own – do you consider essential to any American Revolution buff’s library?

Edmund and Helen Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis; Charles Royster, A Revolutionary People at War; Rosemarie Zagarri, Revolutionary Backlash; Al Young, Liberty Tree: Ordinary People and the American Revolution; John Shy, A People Numerous and Armed; and John Brewer, Sinews of Power

10 // We’re constantly learning new things about the American Revolution. What new or exciting thing about the American Revolution have you recently learned or discovered?

I have recently read several original studies that explore popular reactions to British military occupation in the major port cities during the Revolution and the reconstruction of a legal culture after the Crown courts closed in 1774-1775.

11 // If you could time travel and visit any American colony/state for one year between 1763 and 1783, which colony and which year would you choose? Why?

Although it was not a colony, I would return to Vermont (the Republic of Vermont) in 1778 and witness the writing of the first constitution, a truly radical document.

12 // With all of the recent scholarly chatter about setting aside the ideological and social arguments for why the Revolution happened, do you think scholars should, or can, also set aside the economic argument of why the Revolution happened to focus on how people experienced the war? Do you think scholars can set aside any of these arguments and still study and discuss the Revolution?

Interpretations of the Revolution come and go like consumer fads. Currently, historians favor broad Atlantic perspectives; others produce cultural studies that explore the personal experiences of forgotten Americans. Some of these works are very well done; others are pedestrian. I suspect that political, religious, and economic history will soon make a come back. It will not look like the scholarship produced by an earlier generation. It will be more complex, nuanced, giving proper attention to the lives of African Americans, women, Native Americans, and the poor. And they will be comparative, situating our revolution in a conversation about other conversations, even those of our own times. These studies will not be closer to some imagined truth about the revolutionary past. Revision, after all, reflects a changing present.

5 Comments

Wonderful interview! Good questions and obviously great answers. I really like that you asked what historians had an influence on him and what works he considered essential to his library of the Revolution. I think that is crucial to develop an understanding of how he and others develop their ideas from.

I think he is correct about religion being a trend in developing interpretations of the Revolution. He touches on that in American Patriots which I am currently reading. I also favor his and other historians bottom up approach to the Revolution.

Again, good interview!

Thanks for the compliments, Jimmy. Much appreciated.

Great website, Todd!

Kim! Great to see your comment and hope you’ll return five days a week to consume all our fun (and bite-size) RevWar content. Hope all is well at the Hale-Byrnes House.

I’m just reading American Insurgents and am appreciative of the light it casts on our revolution. Great and insightful interview. Thanks so much