In 1775, almost all Americans could read. This enabled young people to follow the political argument that preceded the shooting war. They were enthusiastic independence men and women even though they were too young to vote or fight.

In 1775, almost all Americans could read. This enabled young people to follow the political argument that preceded the shooting war. They were enthusiastic independence men and women even though they were too young to vote or fight.

Few young men were a better example of this enthusiasm than fourteen year old Joseph Plumb Martin of Connecticut. On April 21, 1775, he was plowing a field about a half mile from his home when the church bells began to ring. He rushed to find out “what the commotion was” and found out that war had begun in Massachusetts. All the “male kind of the people” were volunteering to march to Boston to fight the British. Watching, Joseph wished he was old enough to join them.

A year later Martin persuaded his grandparents, with whom he lived, to let him join the army. According to the law, a man had to be seventeen to join up, but recruiters seldom asked questions about a volunteer’s age. Joseph stayed in the army until America won her independence, eight years later. In his old age, he wrote a fascinating book describing his “adventures, dangers and sufferings” as a Revolutionary soldier.

Twelve year old Ebenezer Fox came from a poor family in Roxbury, Massachusetts. His parents had “bound him out” to work on a neighbor’s farm. He decided the Revolutionary excitement gave him a perfect excuse to run away and “set up a government of my own.” He and a friend headed for Providence, Rhode Island, where they were hired as sailors on an American ship.

These young people felt the spirit of liberty sweeping the country. Typical of them was sixteen year old William Diamond who signed up as drummer boy in the Lexington, Massachusetts, militia company. On April 19, 1775, William Diamond beat “to arms” on his brightly painted drum. That sound brought 70 militiamen to confront approaching British regulars. Young Diamond was in the ranks when the first shots of the war were fired.

Drummers were very important in the warfare of the Revolution. Their various beats gave the soldiers orders in camp, on the march and in a battle. An officer’s voice often could not be heard above the booming muskets and cannon. Drumbeats ordered flank attacks, retreats and other maneuvers. The drummers were as exposed to the bullets that were flying from the enemy’s guns as the soldiers. It took courage to be a drummer.

Other young men served as trumpeters in the cavalry. One of the most famous paintings of the Revolution tells the story of Colonel William Washington (a cousin of George Washington) dueling a British cavalry officer with sabres. Colonel Washington’s sabre snapped and he was in imminent danger of death. From nowhere came his trumpeter, a young black slave about twelve years old, whose name remains unknown. The boy fired a pistol, disabling the British officer’s horse and saving Colonel Washington’s life.

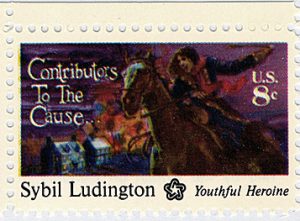

Young women soon proved they too were ready to do extraordinary things. Sixteen year old Sybil Ludington lived in Fredericksburg, N.Y. only a few miles from Danbury, Connecticut. Her father was the colonel of the local militia regiment. Danbury’s warehouses and barns were crammed with tons of food and ammunition for the American army. In April 1777, the British decided to attack it.

Young women soon proved they too were ready to do extraordinary things. Sixteen year old Sybil Ludington lived in Fredericksburg, N.Y. only a few miles from Danbury, Connecticut. Her father was the colonel of the local militia regiment. Danbury’s warehouses and barns were crammed with tons of food and ammunition for the American army. In April 1777, the British decided to attack it.

Landing near Fairfield on Long Island Sound, a 2,000 man strike force marched inland. The Americans were caught flatfooted. Scarcely a shot was fired at the redcoated column as they marched through the stunned countryside. By 3 p.m. the day after they landed, they were in Danbury, burning the town.

That evening, word of the disaster reached the Ludington household. Colonel Ludington turned to Sybil and told her to spread the word among the members of his militia company to muster on the road to Danbury. She leaped on her horse and for the next five hours raced through the darkness, rapping on farmhouse doors with a stick, shouting the alarm. She covered more than 40 miles before she returned home — a ride twice as long as Paul Revere’s.

Colonel Ludington’s regiment joined other Americans in vigorous pursuit of the British. Although most of the enemy reached their ships, they lost dozens of men in skirmishes along the way. They never attempted to march into the interior of Connecticut again.

On the frontier, marauding Indians seized Jemima Boone, the 14 year old daughter of Daniel Boone, and two of her friends while they were canoeing on the Kentucky River. Knowing their fathers and their male friends were aware of their plight and on the way to rescue them, the feisty young women did everything possible to delay their captors.

They fell down and complained of foot and leg injuries. They said they were too exhausted to walk another yard. When the exasperated Indians stole a horse for them to ride, the young women refused to mount it. Boone and his men soon caught up with the harassed warriors and routed them with a blast of gunfire. The young women rode home unharmed.

For sheer daring, few women — or men — could match the courage of sixteen year old Elizabeth Zane. She was the sister of Ebenezer Zane, the founder of Wheeling, West Virginia. In 1782, their small settlement was attacked by the British and their Indian allies. The outnumbered citizens fled to a log fort for safety.

For a while, the men in the fort held off the attackers. But the Americans’ powder supply began running low and they feared they might have to surrender. There was a keg of powder in Ebenezer Zane’s house, about fifty yards from the fort. Several men volunteered to get it but Elizabeth insisted that she should go. The enemy would hesitate to shoot her because she was a woman.

Slipping out the fort’s gate, Elizabeth coolly strolled to the Zane house while the puzzled British and Indians watched her without firing a shot. In the house, she wrapped the keg of powder in her apron and raced toward the fort. The startled enemy opened fire but Elizabeth reached the gate unhurt. The fresh supply of powder enabled Ebenezer Zane and his men to hold out until reinforcements arrived and routed the attackers.

5 Comments

Young people indeed had a big role in that war. Even bigger than most of us would imagine.

However, I only have one nitpick on this article: What about your Loyalist brothers? What about the young men and women who preferred fighting for King George III, rather than independence? Weren’t they important enough to be mentioned here?

In my family research I had been wondering how my 4th great grandfather was allowed to be involved in the war at 12 years old. Now I’m confident restless young Americans would have easily defied their their parents to help establish freedom.

link of interest:

Lemuel Cook 1759-1866

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lemuel_Cook

John gray 1764-1868

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Gray_(American_Revolutionary_War)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Last_surviving_United_States_war_veterans

Anna [Webb] Wilson 1772-1849

https://old.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=wilson&GSiman=1&GScid=40187&GRid=19256321&

Lets not forget the oldest as well…George Wyatt 1721-1800

https://old.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=11010562

Thank you for your article. In my historical fiction novel, my main character is a young person who wants to serve with troops from the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. I am glad that my notion of a young person doing his/her part for freedom isn’t some crazy notion, but that it really did happen. Your information has given me impetus to explore more.