Everyone has heard about General George Washington. Most people recognize the names of Generals Nathanael Greene, Charles Lee, Anthony Wayne, Sir William Howe, and Sir Henry Clinton. But how many have heard about General George Monck? He came very close to winning the American Revolution for George III.

What makes this especially amazing is General Monck’s invisibility. When the Revolution began, he had been dead almost 100 years. But he was very much alive in the mind of another general, whose name most people have struck from the honor roll of American leaders: Benedict Arnold.

When General Arnold, disgusted by the abuse he had received from the politicians in Philadelphia, wrote his first letter to Major John Andre, head of British intelligence, suggesting he might be interested in changing sides, he signed it “General Monk.”

Nothing Arnold afterward said or did revealed more of his grandiose dream of achieving peace, wealth and eternal honor – as well as exquisite revenge against the politicians in Philadelphia.

Born in Norwich, CT, Arnold was a New Englander. This meant his ear was attuned to the memories of the English Civil War, a bitter brawl that darkened the middle decades of the previous century. In that war, General Monck had played a unique role. He had been General Oliver Cromwell’s right hand man. He had not said a word when Cromwell and his yes men in Parliament executed King Charles I. Nor had he protested when Cromwell told Parliament to take a walk and appointed himself Lord Protector.

At one point, demonstrating his loyalty, General Monck turned over to Cromwell a letter he had received from would-be King Charles II, in exile in France. Cromwell appointed Monck his deputy and ruler of restless Scotland, where he slaughtered hundreds when the highland clans revolted.

But when Cromwell died in 1658, and his son Richard proved a hopeless replacement, General Monck began reading other letters from Charles II with more than passing interest. (The mail carrier was Monck’s clergyman brother.) A year later, Monck crossed into England with his army and easily outmaneuvered or defeated rival generals. Soon he was in London, solemnly declaring his adherence to republican principles. But he quietly suggested it would a good idea if the so-called “rump” Parliament dissolved itself.

Soon there was a “Convention” Parliament, in which Monck was a member – while in constant communication with Charles II. At his advice, Charles issued a promise to rule without seeking wholesale revenge against his father’s killers. On May 1, 1660, Parliament invited Charles to become England’s next king. The so-called Restoration era, was soon afloat.

Charles II made General Monck a Gentleman of the Bedchamber, Knight of the Garter and Master of the Horse in the King’s Household. More or less simultaneously, Monck also became Duke of Albermarle and Earl of Torrington in the County of Devon. He was granted The Forest of Bowland and a pension of 7,000 pounds a year — a half million dollars in modern money.

Here was the role that General Arnold dreamed of achieving. It was a dream that vastly overestimated his popularity with the rank and file in the Continental Army. But it was a dream with a noble side to it: the General hoped that if he became the man who restored the American Colonies to George III, the King would show mercy to these stubborn rebels. Some of the foremost generals and politicians – Washington and Jefferson above all – would have to die. But the rest would be spared to grow and prosper in the coming decades, and learn to be grateful to their savior, Lord Arnold, the Duke of Philadelphia.

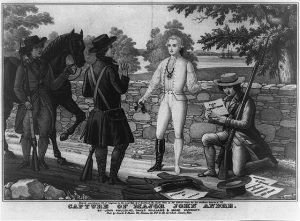

This feverish dream unraveled in ways that might be called providential. Major Andre, on his way back to New York with the Arnold’s plan to surrender West Point and seize control of the Hudson River, was grabbed by three wandering militiamen, who hoped to steal his money and his boots – until they found surprising papers concealed in the latter.

General Arnold, when he heard this news, leaped into a boat manned by soldiers from the West Point garrison and ordered the crew to row him to a sloop that Andre had assumed would carry him back to New York. An enterprising local militia officer had begun bombarding the ship with a small cannon and it had retreated several miles downstream. When General Arnold boarded the sloop, he turned to the soldiers who had rowed him there and urged them to join him in renewed loyalty to George III. Not a single man responded.

Cool ingenious General Monck would never have bolted in such a melodramatic style. He probably would have claimed he had been conferring with Andre in the hopes of luring the British upriver to inflict an horrendous defeat on them. He might have claimed his invitation to the boat crew was part of his performance.

Would a semi-plausible story like this have persuaded General Washington? Probably not. But this cautious gentleman might have freed Andre and allowed General Arnold to retire with honor, rather than reveal such treachery at work in the American high command.

2 Comments

Wonderful!!!!!

Seriously? Too heavy on projecting the Americanized anti-Arnold (pseudo-religious) rhetoric. Sacrifices objectivity for conjecture and subjective projection.