Myth:

The American Revolution started at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775.

Busted:

All of contiguous Massachusetts – except Boston! – cast off British rule in a revolution that swept through the countryside more than half a year earlier, from August to October, 1774.

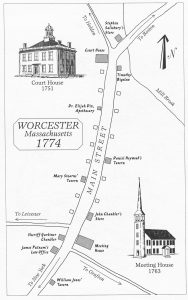

On September 6, 1774, at dawn and through the morning, militia companies from 37 rural townships across Worcester County marched into the shiretown (county seat) of Worcester. By an actual headcount taken by Breck Parkman, one of the participants, there were 4,622 militiamen, about half the adult male population of the sprawling rural county. This was not some ill-defined mob but the military embodiment of the people, and they had a purpose: to close the courts, the outposts of British authority in this far reach of the Empire.

This they did, and with great flare. Lining both sides of Main Street for a quarter mile, the insurgents forced two dozen court officials to walk the gauntlet, hats in hand, reciting their recantations more than thirty times each so everyone could hear. The wording was strong: the officials would cede to the will of the people and promise never to execute “the unconstitutional act of the British parliament” (the Massachusetts Government Act) that would “reduce the inhabitants … to mere arbitrary power.” With this humiliating submission, all British authority vanished from Worcester County, never to return.

So too in every shiretown save Boston: some 1,500 patriots in Great Barrington, 3,000 in Springfield, and so on. In Plymouth, 4,000 militiamen were so pumped up after unseating British rule that they gathered around Plymouth Rock and tried to move it to the courthouse to display their power. The rock stood where it was, but British authority was gone from Plymouth and every other town. The disgruntled Southampton Tory Jonathan Judd, Jr., summed it all up: “Government has now devolved upon the people, and they seem to be for using it.”

What could Massachusetts’ military governor, Thomas Gage, do about the uprising? Nothing. In Salem, the temporary provincial capital, patriots held a town meeting one block from the governor’s office, in direct violation of the Massachusetts Government Act. Then, when Gage arrested seven so-called ring-leaders for calling the meeting, three thousand farmers formed in an instant and marched on the jail, forcing the prisoners’ release. In neighboring Danvers, a town meeting continued “three howers longer than was necessary, to see if he [Gage] would interrupt them.” He did not. “Damn ’em,” he was said to blurt out. “I won’t do anything about it unless his Majesty send me more troops.”

Those troops finally arrived the following April, and it was then that Gage, under extreme pressure, moved to recapture the province that had been lost the previous year. Before sending out his troops, Gage dispatched spies to determine where to attack. They reported that a march on Worcester, a patriot stronghold and the largest storehouse of weaponry and powder, would be disastrous. Gage decided to go after Concord instead.

The military offensive Governor Gage initiated in April 1775 triggered bloodshed and marked the onset of war, but the actual revolution – the transfer of political and military authority from one group to another – preceded Lexington and Concord by more than half a year. That revolution was triggered not so much by the Boston Port Act as by the Massachusetts Government Act, which revoked the core of the 1691 Provincial Charter and effectively disenfranchised the people. The people would not be denied the power of their votes. They rose up as a body, not just to protest Crown and Parliament, but to displace their authority.

What did that really mean? Stay tuned….

Further readings:

In The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord (The New Press, 2002), I present a detailed narrative of the 1774 Massachusetts revolution. In Founding Myths: Stories That Hide Our Patriotic Past (The New Press, 2004), I give a shorter rendition but add a historiographic treatment, showing how histories of the Revolution written by contemporaries included the story, but how (and why) historians of the early 1800s expunged it from the core national narrative. I feature the blacksmith Timothy Bigelow, a figure at the center of the Worcester rebellion, as one of seven protagonists in Founders: The People Who Brought You a Nation (The New Press, 2009). In Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation (Knopf, 2011), edited by Alfred F. Young, Gary B. Nash, and Ray Raphael, I include an essay on Bigelow and focus on the dynamics of a people’s revolution.

Ray Raphael at TEDx:

Video link: Revolution: A Success Story: Ray Raphael at TEDxEureka, Dec. 2, 2012

6 Comments

Enjoyed the article. It is my opinion that many historians tend to focus on the “war” and not really on the revolution. The events prior to Lexington and Concord, altough revolutionary by definition do not fit the definition of war: armed conflict. Soldiers make for better propaganda than debaters.

This was not a revolution as much as the opening up of a full blown rebellion and the genie could not be put back into the box ever again by Gage. The rebellion’s next phase would not be seen until after Bunker Hill when Britain was forced to recognize the Continental Congress as the de facto head of the rebellion.

I just finished reading Ray Raphael’s First American Revolution and it is terrific. It is an important book that shows why ordinary Massachusetts farmers who had been loyal subjects of the king only ten years before became rebels and soldiers willing to give their lives in the Revolutionary War. Raphael shows the importance of the Massachusetts Act when Parliament, as enforced by Thomas Gage, attempted to end local town meetings and trials by juries. Massachusetts townsmen had be ruling themselves for about 100 years and this effort to take away those rights generated tremendous anger and opposition. The writing moves swiftly from one shocking act of defiance to another. I highly recommend this book.

Have read your book several times and given several copies as gifts over the years. Thank you for you tremendous work.

This is an excellent article on the foundations of the American Revolution, to often ignored in favor of the more visually inspiring military conflict. The lesser known background details of such events, for me, are of greater interest, as they bring the full story closer to home. Clearly, it was the ordinary people, the farmers and local tradesmen, who created the opportunity for permanent change to occur, allowing the political leadership, subsequently, to create a new format for self governance. However, it was British government’s failure to recognize the significance of 100 years of essentially self-governance in the colonies that led to the American Revolution.

I, too, enjoy Ray Raphael’s works and often return to them to re-read sections dealing with my interest at that moment.

And, I agree with the thought that accounts built from the ground up–based on common person’s stories–are most enjoyable. I also believe they get the point across most effectively: people like soap operas and that’s what history is.

I take one exception to Richard’s comments–it’s actually closer to 150 years than 100 years of self-governance. Most folks have a difficult time comprehending that sort of time span so I often tell them it’s the equivalent of the time between now and the Civil War.