The economic life of the Southern colonists was also most positive as the colonial period continued. Up until the end of French and Indian War, when strict supervision began, the British had allowed the colonists a fair degree of freedom in all their economic endeavors. While the mother country had attempted to stop trade with foreign countries, minimized manufacturing competition within the colonies, and required raw materials to be obtained from British firms, the colonies were unquestionably prospering.

The South faired well in the economic atmosphere of the times. The Southern colonies, in fact, held the largest share of colonial wealth by 1774, based on estate probate records of the 13 colonies. The average estate for the top one percent of the Southern wealthy was $238,000, a figure twice as large as the largest estates in the Northern colonies. The first American millionaire emerged in this time. The largest estate of record was that of Peter Manigault who was a South Carolina planter and lawyer with assets of $2.5 million. Indeed, 9 of the 15 largest estates (based on non-human assets) were in the South, and 8 of the 9 were in South Carolina. Research has indicated that the South held approximately 46% of the wealth, with the Middle colonies 29% and New England only 25%. Of interest was the composition of the Southern wealth, being 45.9% in land, 8.8% in livestock, 5.1% in personal goods and, incredibility, 33.6% in Black slaves and indentured servants.[32]

The wealth of the colonial South grew in spite of the rather primitive state of the financial system. In most cases financial services were provided by merchants who gave credit to buyers of their goods. There were no commercial banks, stock markets or other formal institutions to handle financial transactions. Since the British Parliament would not let English coins leave the British Isles, the money supply was made up of gold and silver coins mostly of Spanish origin, and paper currency issued by the various colonial legislatures. There were occasional shortages of coinage, but generally the money structure was not especially restrictive. The percentage of the money in circulation varied by colony and time period, but it is generally accepted that paper currency rarely exceeded more than 50% of the money supply. The North American colonies were among the earliest governments to issue paper currency, as no European nation had authorized its use on such a vast scale. Even in England, paper currency was not encouraged and it was rarely used as legal tender for payment of debts in favor of coin specie.[33]

With the highest economic level and an unmatched standard of living, the colonies, and especially the Southern colonies, were the premium locations in the world to live. It was such a thriving environment for the colonist in the 1770s that the population grew at near its biological limit. The estimated gross product was $2.25 billion annually, which incredibility was one-third that of the mother country.[34] In the South the creation of wealth was almost entirely through the development of valuable agricultural crops. In the upper South of Maryland and Virginia, tobacco was the crop with the greatest market significance. This tobacco culture also moved with the settlers to North Carolina, but was never as significant in production as in Virginia and Maryland due to the difficulty in getting the crop to market with few Tidewater rivers to transport it. The climate and the soil were perfect for this type of crop. By 1763 the tobacco exports in Maryland and Virginia was approximately 100 million pounds worth some $6.3 million. Even in North Carolina the annual production was at 2 million pounds at that time, and ten years later the production had doubled.

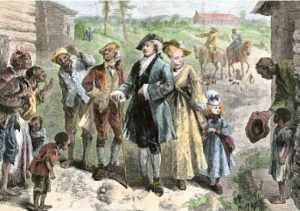

Tobacco was a relatively easy crop to grow, and harvest. In order to expand tobacco cultivation, planters who acquired or held large tracts of land turned to slavery to work the fields. As a result of this desire for greater wealth, large plantations become more common. Some of these plantations supported over 100 black slaves to tend the tobacco crops. The average slave could maintain 3-4 acres of tobacco at a time.[35]

In North Carolina, the home of mainly small farmers, another crop of a different type emerged to some significance-forestry. The settlers began to fall pine trees for the naval stores of tar, turpentine and the lumber for use in British and New England shipyards. Naval stores of tar, pitch and turpentine were required for naval and merchant vessels. The Cape Fear River Valley, with the abundance of rosin-rich longleaf pines, soon became the production center for naval stores, with Wilmington as the shipping point.[36]

The cultivation of rice and indigo played the same role as tobacco did for the colonies of the upper South for South Carolina and Georgia. Rice was the most important crop of the lower Southern colonies. The cultivation of rice began in the swampy low country as early as 1700, but it was slow to evolve until McKewn Johnstone invented a method of flooding the fields using the tides to control the flow of water of the surrounding rivers and streams. Unlike tobacco, rice cultivation was physically quite demanding, and usually unhealthy. The rice, planted from March to May on plantations of 50 to 100 slaves, was harvested in August or September in stagnant water, which exposed workers to disease. Thus, the rice plantations of the lower South were especially harsh environments as compared to the tobacco operations of the upper South.[37] Rice was very profitable, and estimates of 25% profit from a plantation of 200 acres worked by 400 slaves were achieved in the 1770s. The revenue per slave in this period were $830-$2485.[38] By the 1770s the rice production supported exports from South Carolina as high as $18 million per annum. The rice was shipped in barrels from ports like Charleston or Savannah to Holland or Germany by way of Britain. This accounted for 60% of the South Carolina’ production. The remaining crop was shipped to Portugal, Spain, Italy, and even to other colonies like New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.[39]

In 1738, Eliza Lucas migrated to South Carolina from Antigua at age 16 to take over responsibility for three of her father’s recently inherited plantations.[40] She decided that the semi-tropical region was ideal for the growing of indigo, which was in great demand in the British textile industry for its brilliant copper and purple dye. Thus, she was credited for introduction of this new and profitable crop in the South. Like tobacco, indigo was grown exclusively for export. The push to indigo production was prompted by an act of Parliament in 1748, which began to pay a bounty of sixpence ($2.25) for each pound of dyestuff imported to Britain from the American colonies. Although this indigo was somewhat inferior to that grown in the West Indies of the French and Spanish colonies, it was successful in South Carolina and Georgia because of the governmental support of the American colonial market by the British.[41]

Indigo was grown in light, rich soil on high ground. The leaves were cut from the plant twice per year, and boiled in water to extract the dye. This product was dried, pressed into small blocks, and put into casks for shipping. A skilled slave could care for up to two acres of indigo plants and produce 120 pounds of dye worth $1800-$2700 per year in the 1770s. No other crop could produce a greater income per acre during the colonial period.[42] In the twenty years before the Revolution, exportation of indigo was at its greatest from this region, with an average of 500,000 pounds per year. During a few of these years, exports reached one million pounds, valued at more than $18 million.[43] Based on the cash crops of tobacco, indigo and rice, the South provided the setting for the establishment of a distinct and elite group, the planter class. These planter elite were to rise in social and economic standing to become the defined Southern aristocracy. In order to rise to this level, a planter had to acquire both land and slaves, which typically was at least 500 acres and 20 slaves. Estimates put the total number of white plannter households in Virginia to 3 to 10 percent after 1750.[44]

The great planters of the South were not only economically and socially successful, but they also gained the political control of the colonies. As these planters grew in wealth, they were able to pursue their personal activities without regard for the specific day-to-day operations of the plantation. Though they engaged in numerous interests, the pursuit of the political realm was the one engagement that served not only to influence the course of the colonies, but it also served their egos. The lifestyle of the Southern planter in the 1770s, in contrast to their Northern peers, was in many ways like that of the landed gentry of England.[45] The great planter families, like those of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, were among the Southern planter class that dominated the colonial legislatures of their time. These rich planters gave the Southern colonial society “a cohesion” and made it easier to maintain the public order since the humble immigrants were already conditioned to accept the aristocracy as the ruling class.[46]

An indication of the economic condition of many of the great Southern planters is exemplified by the correspondence of William Fitzhugh, a Virginia tobacco farmer and part-time lawyer, who managed his estate along the Potomac River in Northern Virginia:

“The plantation where I live contains a thousand Acres, at least 700 Acres of it rich thicket, the remainder good hearty plantable land,…together with a choice crew of Negros,…twenty-nine in all, with Stocks of cattle and hogs at each Quarter; upon the same land is my Dwelling house, furnished with all accommodations for a comfortable and gentile living,…with 13 rooms in all,…nine of them plentifully furnished with all things necessary and convient, and all houses for use well furnished with brick Chimneys, four good Cellars, a Dairy, Dovecoat, Stable, Bar, Henhouse, Kitchen and all conveniences,…a Garden a hundred foot square,…together with a good Stock of Cattle, hogs, Mares sheep and etc.”

The documented account of Fitzhugh’s estate serves as an example of the great strength of the colonial economy in the South.

These most aristocratic lifestyles of the great planters were based on the significant agricultural foundation, where high value crops were produced with the toil of the ever-growing slave population. While not all agricultural enterprises were as successful and impressive as those of the great Southern planters, it is of significance that farming was indeed the key to the relative high standard of living in the colonial South. With 3 of every 4 families engaged in farming, it ultimately defined the economic, social and political fabric of their lives.

An event occurred in 1619 that would profoundly impact the Southern colonies to the present day. In that year the first 20 black slaves were brought to Jamestown, Virginia in a Dutch ship. These Blacks had been kidnapped from their homes in Africa by traders and sold to this Dutch ship captain. After arriving in the colony, he sold these blacks to the Virginia settlers. These first blacks were treated like indentured servants, and eventually were freed. But soon the idea developed that the blacks should be kept as slaves to work the fields. Thus, began the dark period of legal slavery in the South.

In the early days, the Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese slave traders found a better market for their human goods in the Spanish colonies to the South, so the slave population grew slowly in Virginia. Another significant factor that held the slave population down at this time was that a slaves cost 2-3 times more than indentured servants. Thus, the numbers grew slowly, and by 1649 there were only 300 black slaves in Virginia. In 1662, the Royal African Company was chartered under the protection of the crown to supply the American colonies with slaves. The numbers of slaves began to grow, especially after 1680. The beginning of the shift from use of white indentured servants to black slaves occurred for a variety of economic, political and social reasons. Economic conditions had improved in England after 1675, and those willing to sign indentured contracts began to decrease. With the expansion of the size of tobacco fields on large plantations, and with a shift in attitude towards obtaining non-temporary labor, the black slave was considered the best alternative.[47]

Black slavery was not a new phenomenon during the colonial period. It was indeed an established institution in the Caribbean and other areas in the Western hemisphere. Of interest is the fact that the trade of Africans to the American colonies represented only 6% of the total of such trade. The profit margins of those that transported slaves were a mere 8% to 12% as a rule. Plantations in the Caribbean had begun to shift to black slaves by 1640, when most of the arable land was occupied and opportunities for white immigrants diminished. The sad reality of slavery in the colonial period was that the major beneficiaries were the consumers of tobacco and sugar. These products were luxuries in Europe, but over the years the prices had fallen which made the decision to shift to black slaves more expedient.[48]

Once the idea of black slavery took hold in the South, it progressed rapidly. In the six years beginning in 1683, the population of blacks in Virginia grew from around 3,000 to 5,000. The pace of slave importation increased to some 1,800 per annum by 1705, and by the time of the Revolution, the colonies of Virginia and Maryland had a total black population of 206,000.[49] This growth in slave trade was profound even from a purely economic standpoint, for the average value of a slave in Virginia in the 1770s was £30 ($2700). While they were expensive, in South Carolina an entire ships’ slave cargo was usually auctioned off in a single day, with each planter acquiring from two to twelve slaves.[50]

The motivation to obtain the black slave was indeed recognized and exploited. The typical slaveholder who used half of the output of a slave, and sold the other half could raise his standard of living by 15-20 percent.[51] There was some differing slave holding statistics between the planters in the upper South in the Chesapeake region, and those in the lower South centered around Charles Town. The average number of slaves owned by the Chesapeake planters was 8-10, and only a few held more than 100. In the Charles Town Lowcountry region, covering southeastern North Carolina, South Carolina and Northeastern Georgia, planters typically owned some 25-30 slaves, and a group of 79 planters held 100 or more slaves at their plantations.[52] Thus, it is not surprising that black slaves made up two-thirds of the population of South Carolina in 1775.[53] In the North, only New York, Newport, and Providence had slave population of over 10%, but in Charles Town, the majority of the city’s population was slave.[54]

Conditions on the plantations were harsher to blacks in South Carolina than in the upper South, primarily because the owners did not live year around on their plantations. These great planters of South Carolina spent much of their year in quarters in Charles Town, and left control to hired overseers. The reputation of some of these overseers was one of cruelty toward blacks. Because of the vast number of black slaves in South Carolina during the colonial era, the laws that evolved were also harsher. In the tobacco colonies the slave code was based on English law, which gave at least limited rights to slaves. But in South Carolina the slave code was based on Spanish law, where the owners maintained “absolute” power over their slave property.[55]

While the moral aspect of slavery, as an evil, was present in the colonial era before the Revolution, it was not considered of overwhelming social, economic or political significance at the time. Since the land in New England was not as favorable for crops as in the South and the growing seasons were shorter, the Northern colonists did not pursue slavery with as much zeal as in the South. While the North never depended on slavery to any significant degree, primarily on economic circumstances, they did condone slavery.[56] In the South, slavery was considered an economic reality. The dependence on slavery in the South was so great that even the most revered framer of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, who wrote the phase “that all men are created equal”, would not release all his slaves until the death of his wife, when the economic impact was past.

Another curious group of human servants to the white colonist also came to North American up until the their services were assumed by black slaves over time. These colonists were indentured servants who came to the colonies to serve their masters under contract for a period of 4 to 7 years. Thousands of willing white immigrants came to the Southern colonies in this way to seek a better life and, perhaps, to eventually acquire land. Between 1630 and 1680, some two-thirds of all immigrants to Virginia were indentured. In return for transportation across the Atlantic, food, clothing and shelter, these people agreed to be indentured servants under a legal contract for a stated period. These contracts were of differing prices depending on the skills, age, sex, length of contract and, of course, the local demand for their talents.

Most indentured servant males served farmers to work the fields, while females handled the household chores. After their period of indenture, these people would usually receive some funds to help them get started in their new life in the colonies as free people. Even though they were servants for their indentured period, their general living conditions were not any worse, in most cases better, than they had known in their homeland. After 1680 black slaves replaced indentured slaves as the primary source of bonded labor in the Southern colonies. According to estimates, this unique method of supplying labor to the colonies brought some 350,000 indentured servants to North America during the colonial period.[57] By 1774, the indentured servant population had decreased to around 2%.[58]

Although the support of the agricultural economy engaged the majority of population of family farmers, great Southern planters, black slaves and indentured servants, another occupational group constituted from 15 to 20 percent of the white population- merchants and artisans.[59] This group was a widely dispersed group across the economy, and were concentrated in the towns and villages of the South. During the colonial era, the urban areas served as the commercial centers, where both merchants and artisans pursued their work. The concept of a factory was not a reality in this commercial environment, and they were overtly discouraged by various British regulations in order to restrict any manufacturing competition with such firms in the mother country.

[32] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pg. 219-220.

[33] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pg. 163-168.

[34] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pg 230-234.

[35] John Richard Alden, The South in the Revolution, 1763-1789, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1957), pg. 18-19.

[36] William S. Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989), p. 135.

[37] John Richard Alden, The South in the Revolution, 1763-1789, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University,1957), pg. 19-20.

[38] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), p. 81.

[39] John Richard Alden, The South in the Revolution, 1763-1789, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University,1957), pg. 20-21.

[40] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press,

1988), p.78.

[41] John Richard Alden, The South in the Revolution, 1763-1789, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University,1957), pg. 21-22.

[42] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), p.79.

[43] John Richard Alden, The South in the Revolution, 1763-1789, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University,1957), p. 22.

[44] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), p.81.

[45] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pg. 81-82.

[46] Lawrence James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994), p.41.

[47] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pg. 84, 91-100.

[48] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pg. 99-102.

[49] William B. Hesseltine, The South in American History, (New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1946), pg. 38-39.

[50] Robert M. Weir, Colonial South Carolina, (New York: Kraus-Thomson Organization Press, 1983), p. 177.

[51] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), p. 219.

[52] John Richard Alden, The South in the Revolution, 1763-1789, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University,1957), p. 42.

[53] Authur M. Schlesinger, The Birth of the Nation, 6th ed., (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1976), p. 66.

[54] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), p. 99.

[55] William B. Hesseltine, The South in American History, (New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1946), pg. 65-66.

[56] Authur M. Schlesinger, The Birth of the Nation, 6th ed., (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1976), pg. 67.

[57] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press,

1988), pg. 91-95.

[58] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), p. 98.

[59] Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pg. 125-126.

2 Comments

Hi there,

Nice overview, but I thought that Jefferson never freed his slaves, and that it was Washington that freed his slaves upon the death of his wife.

I saw that too. Jefferson did free a few of his slaves. Notably several of the Hemings family.