BOOK REVIEW: Novels, Needleworks, and Empire: Material Entanglements in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World by Chloe Wigston Smith (Yale University Press)

Novels, Needleworks, and Empire: Material Entanglements in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World by Chloe Wigston Smith details how processes and objects of the domestic life were inherently intertwined with colonialism. Smith argues that while white women were able to gather education and form bonds through their domestic works, the creations of Black and Indigenous women makers existing with the colonial framework were either stripped of their individuality (unless they were creating something outside of the European colonial world), or were lost to time altogether.

Smith breaks down several novels, needleworks, samplers, and other domestic objects both practical and aesthetic to analyze how these creations fit into the eighteenth-century colonial world on both sides of the Atlantic. Ultimately, Smith highlights the European settler “value of material objects to colonization and religious conversion,” (page 136) as well as “fabric worlds [being] marvels of skill and education, exemplif[ing] the complex material forms that enmesh[ed] the work of craft with the agendas of colonialism.” (p. 217)

Smith breaks down several novels, needleworks, samplers, and other domestic objects both practical and aesthetic to analyze how these creations fit into the eighteenth-century colonial world on both sides of the Atlantic. Ultimately, Smith highlights the European settler “value of material objects to colonization and religious conversion,” (page 136) as well as “fabric worlds [being] marvels of skill and education, exemplif[ing] the complex material forms that enmesh[ed] the work of craft with the agendas of colonialism.” (p. 217)

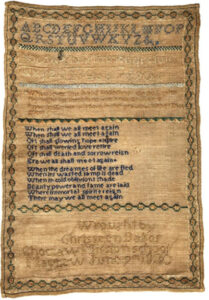

Smith lays the groundwork of the eighteenth-century material world in describing how white women in both Europe and the colonies relied on needlework, samplers, and the making of domestic goods as not only a means of education, but also as a type of “resume” of domestic competency to ones’ prospective or future husband. “Knitting in particular was used to teach girls numeracy and arithmetic.” (p. 156) Through needlework, women and girls were able to “articulate their possession of numeracy, literacy, and material skills” and display “their abilities to use these skills to control the circulation of household textiles and clothes. . . . Their experiments entangled feminine handiwork with the politics of the Atlantic world and settler colonialism, marking and making space in this domestic work and joining manual knowledge to urgent questions about the freedoms and rights of the makers themselves.” (p. 113)

Creating such objects was not only means of education and showing ones’ skills to a potential husband, but was also a way for women, and especially girls coming of age, to ruminate, navigate, and reconcile their place in the entangled colonial Atlantic world. Smith explains that “white women, in particular, depend[ed] on material objects and needlework to negotiate the corrupt domestic relations produced by empire, even as this dependence fail[ed] to resolve colonial corruption. In the contact zones, material culture [made] visible alternative forms of kinship between white women, Indigenous women, and enslaved women, which disclose the exploitation and violence of Britain’s colonial systems.” (p. 37)

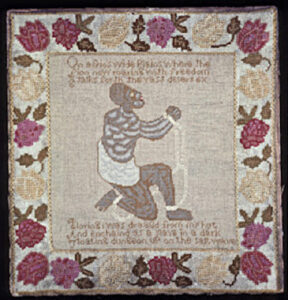

An example of European women grappling with colonialism and slavery can be found in two needleworks the author analyzes in which a tapestry sampler (that had been reproduced several times over) depicts a kneeling enslaved person with accompanying verses about the evils of slavery. The image had originally come from an anti-slavery cameo piece by Josiah Wedgewood with the phrase, “Am I not a man and a brother?”

Given the size and shape of these needlework tapestries, Smith and other historians theorize these works could have been used as chair covers. The author then highlights the uncomfortable point of how such pieces “turn the suffering of their subject into part of the furniture of the domestic interior.” Smith goes on to question what it meant “for a person to sit down on the desperate supplications of an enslaved man, shown kneeling and enchained? Did this generate feelings of discomfort or did these needleworks proclaim to visitors that the suffering of the enslaved should and could not be avoided?” (p. 221) Could such crafted materials effectively communicate messages of abolition without falling to exploitation as means of decoration and vanity? On the other side of the spectrum, needleworks depicting Black and enslaved peoples within the colonial Atlantic world were often rife with racial biases and symbolism. For example, “European portraits of Black sitters often reduced their physical proportions, depicted them as children, or confined them to the background of the composition.” One piece depicts a “Black attendant physically less than half the size of the seated white woman. His smaller stature indicates his lower status and likely his young age. Enslaved children were favored as domestic attendants in aristocratic and merchant households.” (p. 182)

What about the material works from Black and Indigenous makers? Smith notes that while few samplers from Black women and girls exist within the museum setting, even those pieces were likely done by free people or within the colonized setting. Smith explains how “museum provenance favors needlework pieces passed down through the family line, and such structures of inheritance, rooted in the right to property, excluded thousands of families. The missing provenances for samplers and needlework by girls and women of color echo other losses in the archives. . . . While the makers of color discussed [here] were most likely not enslaved, collections of needlework from the long eighteenth-century reflect the archival absences produced by the slave trade and white supremacy.” (p. 80)

Smith notes examples of Black and Indigenous girls creating needlework in the European-centric framework which forced them to adhere to the “civilized, western” view of womanhood. “The [Choctaw Mission School] in Mayhew, [Misssissippi] was one of many that sought to assimilate and convert Indigenous girls—and relied on sampler making to enforce cultural imperialism.” (p. 108) In a similar vein, assimilation via missionaries was evident in the “complex ways that handiwork and maker’s knowledge operated as violent tools of colonialism and religious conversion . . . samplers made by girls in Sierra Leone . . . were forced by their Christian teachers to inscribe British racism into their work and to defend, in thread, their moral and spiritual worth.” (p. 225)

But the eighteenth century Atlantic world did not solely revolve on the European worldview. Smith details the importance of Wampum making to Indigenous communities, the likes of which white, European women would try to replicate in their own works as a type of appropriation. Smith notes that the front plates of many trans-Atlantic novels featured Indigenous people in “exotic” looking attire which reduced them to decorative adornments of pictures hanging in homes. Smith explains, however, that in the novel Euphemia (1790), “maternal bonds between English and Indigenous women soften the hardships shared by colonizers and colonized. . . . Euphemia’s contact with North American Indian nations centers on domestic exchange and frequently includes objects such as handkerchiefs, aprons, and textiles. Euphemia’s experiences in New York articulate how women, families, and feminine material culture supported Britain’s imperial ambitions, as well as how female kinship—both national and intercultural—might temper . . . the violence of the colonial conquest.” (p. 58) Despite this colonial and imperial framework, there is evidence in various needleworks of women and girls of all races who creatively claim “their identities and rights through the subtle and significant changes they made to the small space of their samplers.” (p. 112)

Smith ties the material objects of the eighteenth-century Atlantic world to how we interact with material objects in this century, arguing “thread, paper, and ink [of the eighteenth century] reach into nineteenth century and up to the present day.” (p. 218) Today, art, objects, clothing, etc. is still created with the intent to mirror and influence social issues, even fundraise or draw greater attention to an issue. Smith cites characters in the novels The History of Sir George Ellison (1766) and The Woman of Colour: A Tale (1808) as the “people who participate most avidly in fashion culture are the same individuals who support plantation violence or subject people of color to racism.” (p. 177) The line from this sentiment to now could be drawn to fast fashion and sweat shop exploitation of workers. Women and girls in the eighteenth century up through emancipation in both the United Kingdom and America “created a wide array of domestic and personal objects decorated with antislavery texts and images, including ceramics, reticules and work bags, handkerchiefs, pincushions, needle cases, patch boxes, fobs and seals, and children’s toys.” (p. 223) The same could be said today of creating an exclusively designed t-shirt, for example, to raise money for a specific cause while at the same time drawing more attention to said cause.

Chloe Wigston Smith’s argument that the material entanglements of the eighteenth century have endured to today is evident in such examples. And with the greater interconnectedness of the world in this age, issues of imperialism and racial injustice are woven just as tightly into our society and its material creations.

PLEASE CONSIDER PURCHASING THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON IN CLOTH or KINDLE. (As an Amazon Associate, JAR earns from qualifying purchases. This helps toward providing our content free of charge.)

2 Comments

In the first paragraph, why did the reviewer capitalize indigenous and black but not White?

Capitalization in this article is consistent with current AP guidelines:

https://blog.ap.org/announcements/why-we-will-lowercase-white#:~:text=AP%20style%20will%20continue%20to,commentary%20in%20making%20these%20decisions.