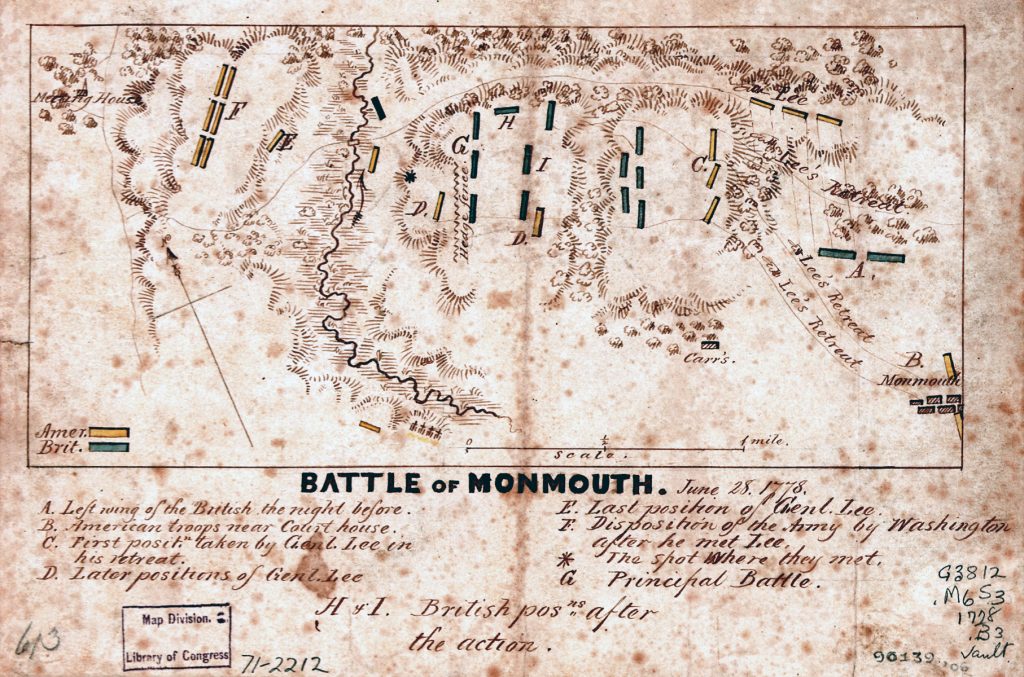

The scene is one of the most famous in the annals of the American Revolutionary War. The commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, Gen. George Washington, confronts his second-in-command, Charles Lee, in the midst of a retreat by Continental Army forces during the Battle of Monmouth Court House on June 28, 1778. Washington arrives at the battlefield riding his white steed; Lee rides up to meet him on his brown horse. Washington asks, in an angry voice, what is the meaning of the retreating soldiers he sees? A baffled Lee, expecting praise instead of sharp words, stammers a response. The two men exchange more harsh words and Washington rides off to organize a delaying action against oncoming enemy forces. Legendary for his composure, at this moment Washington lost it.

But did Washington use swear words in speaking with Lee during that verbal confrontation? Many popular histories of the war and battle say he did. Two sources indicate Washington swore, one from a story told by Maj. Gen. Charles Scott and the other from a story told by Maj. Gen. the Marquis de Lafayette. Both recollections were made decades after the battle by generals who were likely not present at the meeting and who had a grudge against Lee.

On the other hand, we have testimony from the court-martial trial of Charles Lee by several officers who were present at the fateful verbal encounter. The testimony was taken within a few weeks of the day of battle. This testimony has far more credibility than Scott’s and Lee’s post-war recollections. A close review of the testimony indicates that Washington likely did not swear and that Scott’s and Lafayette’s recollections made years after the event are not credible.

Here is a quick review of the background facts.[1]

On June 26, 1778, Lee was given command of many of the Continental Army’s best troops with orders from Washington to attack the rear of British general Henry Clinton’s column near Monmouth Court House, New Jersey. The next day, Washington gave Lee somewhat vague orders to attack the rear guard of Clinton’s force. Washington and his following army, six miles away, would then march to arrive at the scene of battle to support Lee.

Lee intended to attack the enemy’s rear guard on June 28, but instead he retreated in the face of Clinton’s bold move to reverse his march with some 6,000 troops. Crucially, two of Lee’s subordinate major generals, Charles Scott and William Maxwell—without orders and without informing Lee—moved more than half of his command off the field. Faced with the possible destruction of the balance of his force, Lee ordered a general retreat while conducting a skillful delaying action.

Many historians have been quick to malign Lee’s performance at Monmouth. Many of his contemporaries did so too. After the battle, Lee was convicted by court-martial for not attacking and for retreating in the face of the enemy. I believe this was a miscarriage of justice, for the evidence shows Lee was unfairly convicted and had, in fact, by retreating, performed an important service to the Patriot cause by saving his troops from possible destruction. The guilty verdict was more the result of Lee’s having insulted Washington, which made the matter a political contest between the army’s two top generals—only one of whom could prevail.

After the court-martial, Lee faced a host of threats to duel. He actually did duel one of Washington’s most loyal aides, Lt. Col. John Laurens; the contestants fired pistols at each other at close range and Lee was slightly wounded. Lee then barely avoided duels demanded by major generals Baron von Steuben and Anthony Wayne. One of Lee’s aides tried to provoke another of Washington’s talented aides, Alexander Hamilton, to a duel. In the end, Congress upheld Lee’s sentence to be suspended from the Continental Army for one year; Lee never returned to his position.

At his court-martial, Lee tried to put the blame for the retreat of his force at Monmouth where it properly belonged—on Charles Scott. A gruff and rough frontier leader from Virginia with a strong personality, Scott resisted and tried to turn the blame onto Lee. He succeeded. He had gotten to Washington first after the battle and unfairly blamed Lee for the initial retreat of Lee’s force.

Scott’s grudge against Lee for exposing his unwarranted retrograde movement at the court-martial trial continued for many years after the war. As an elderly man in the early nineteenth century, when asked if General Washington ever swore, Scott concocted a fanciful story about Washington at their first meeting during the Monmouth battle:

Yes, once. It was at Monmouth and on a day that would have made any man swear. Yes, sir, he swore on that day till the leaves shook on the trees, charming, delightful. Never have I enjoyed such swearing before or since. Sir, on that ever-memorable day, he swore like an angel from heaven.[2]

Scott likely was not an eyewitness to the exchange since at the time of the incident he was commanding his brigade more than a half-mile away. His story is completely refuted by the court-martial testimony at Lee’s trial, yet many historians continue to repeat the story as if it were or could be accurate.

Unlike Washington, Scott was known for using crude language. In 1792, when Washington was considering whom to appoint as commander of the United States Army in the Northwest Territory, according to historian Mary Stockwell, he considered General Scott but “dismissed him as a drunkard better known for his foul mouth than for any bravery on the battlefield.”[3] The authors of Rebels and Redcoats wrote that Scott was “a connoisseur of profanity” who “was always quick to display his own and to admire invention in that of others.”[4]

Indeed, Scott’s remarks were in response to a friend of his who was trying to cure Scott of his habit of employing profanity. The friend asked if Washington ever swore, hoping to show that Scott should follow his pristine example. Thus, Scott’s story insulted both Washington and Lee, and was an attempt to put himself in a better light by bringing Washington down to his level. He also insulted the Christian religion by suggesting that angels swear. It was a remarkable performance by the conniving Scott.

In addition, Scott had a motive to criticize Lee. Scott wanted to deflect criticism of the generalship in the first part of the battle from him, where it rightly belonged, to Lee. At his court-martial, Lee blamed Scott.

Scott’s best biographer, Harry Ward, wrote that there was no evidence that Scott was present at the famous meeting between the Continental Army’s top two generals, and that Scott’s story was “unsubstantiated.” Ward added, “For Lee to be made a scapegoat was a face-saving measure for Scott, whose own distant retreat was inexplicable and a major cause for the failure of the attack during the first phase of the battle.”[5]

Lafayette, during his return trip to the United States in 1824, first told the story that at the famous confrontation at Monmouth, Washington ended the conversation by calling Lee “a damned poltroon.” Lafayette’s story apparently first appeared in Henry B. Dawson’s history of United States battles, published in 1858. According to Dawson, Lafayette told the story on the piazza of Vice President Daniel D. Tomkins’s residence at Staten Island the morning of August 15, 1824. It was the Frenchman’s first stop on his triumphant 1824-1825 tour. Dawson added in a footnote, “General Lafayette referred to it as the only instance wherein he had heard the general swear.”[6]

Lafayette’s story, told some forty-six years after the battle and at a time when Lee’s reputation was poor, is not credible.

As with many recollections of Revolutionary War veterans written in their later years, Lafayette’s are not always accurate and are best used when there is corroborating evidence from other sources. In his memoir of the war written in 1779, within a year of the battle, Lafayette did not mention any swearing. Instead, he appropriately focused on the one phrase the made the commander-in-chief most angry: “‘you know,’ Lee said to him, ‘that all that [attacking the enemy] was against my advice.’”[7]

In addition, Lafayette and Lee, while they respected each other during the battle, had been antagonists. When Lee arrived at Valley Forge from his long captivity, Lafayette objected to Lee’s criticisms of Washington and of the Continental Army’s training. Lafayette, using the third person, wrote candidly of his relationship with Lee, “as one of them was a violent Anglomaniac [Lee] and the other a French enthusiast [Lafayette], their relationship was never peaceful.”[8] Lafayette’s views of Lee must be understood in this context. In addition, Lafayette was not present at the Washington-Lee meeting.

Mark Edward Lender and Garry Wheeler Stone, in their seminal work on the battle of Monmouth Court House, agree that both Scott’s and Lafayette’s recollections were “nonsense.”[9]

There is one more source to consider. Private Joseph Plumb Martin, who was half-a-mile away with Scott’s detachment, wrote that he witnessed the confrontation but that he was “too far off” to hear the exchange. Martin claimed that some of the soldiers who were closer to the generals had told him that they had distinctly heard Washington say “d—n him.” He conceded that he was not sure whether Washington had expressed those words since “it was very unlike him, but he seemed at the instant to be in a great passion; his looks, if not his words seemed to indicate as much.” As will soon be seen, Martin’s observations in the prior sentence are credible, while what he heard others claim Washington said, not so much.

Here is the story as I have reconstructed it, based on court testimony made a mere several weeks after the battle. Washington’s arrival on the battlefield came at a confusing time for Lee’s detachment, with some regiments retreating and a few others organizing to make a stand. Lee made matters worse by failing to keep his commander properly informed of developments. Early in the battle, before the retreat, Lee had sent a messenger to inform Washington of his plans to cut off the rear guard of the enemy, about 1,500 to 2,000 troops. The messenger, a volunteer aide of Washington’s, Dr. James McHenry, informed Washington of Lee’s “fixed and firm tone” that his plan would certainly succeed.[10] McHenry’s report may have raised Washington’s expectations, so that when the Virginian saw disorganized elements retreating, he became even more bitter than he otherwise would have been.

While Washington and his aides discussed how to dispose of his arriving troops, they stopped a civilian riding toward them and asked him for news from the front. The man responded that a fifer walking nearby told him the army was retreating. When asked whether he served in the Continental Army, the fifer responded in the affirmative and added, “the Continental troops that had been advancing were now retreating.” The fifer’s response “exceedingly surprised” Washington and he appeared “to discredit the account.” He threatened the fifer with a whipping if he spread his views to any other person and put him under the guard of a cavalryman.[11] Moving fifty yards forward, Washington and his party met more stragglers with similar accounts.[12] An exasperated Washington sent two of his aides, lieutenant colonels Robert Harrison and John Fitzgerald, forward to gain information at the front.[13]

Washington met the first columns of retreating troops, Grayson’s and Patton’s Regiments, and inquired of their officers the reasons for the retreat. None of them had a good answer. The 2nd New Jersey Regiment, in Maxwell’s Brigade, appeared on the scene, with its officers expressing displeasure at the retreat. When the commander in chief asked Col. Israel Shreve about “the meaning of the retreat,” the officer smiled, despite British soldiers burning down his house in southern New Jersey on June 24, and responded that “he did not know.” Maj. Richard Howell, in the rear of the 2nd New Jersey and brigade major for Maxwell’s Brigade, “expressed himself with great warmth at the troops coming off, and said he had never seen the like.” Understandably, as one of his aides recalled, Washington “was exceedingly alarmed, finding the advance corps falling back upon the main body, without the least notice given to him.”[14]

Washington, his temper simmering to a boil, spied Lee on some heights fronting the Middle Ravine and rode up to him, as Lee rode down to meet his commander.[15] The time was about 12:45 p.m. and an encounter that would have grave implications for Lee’s career was about to occur.

The facts of the famous meeting are not in dispute. They are based on first-hand witness testimony at Lee’s court-martial held less than a month after the battle ended.

Upon reaching Lee, Washington demanded, in an angry voice, “I desire to know, sir, what is the reason for this disorder and confusion?”[16] The commander-in-chief’s “severe” tone shocked Lee, who had been expecting “congratulation and applause” for avoiding a crushing defeat.[17] According to the most credible account, from Washington’s aide-de-camp, Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman, Lee stammered in return, “Sir? Sir?” After recovering, the subordinate insisted, “from a variety of contradictory intelligence, and from his orders not being obeyed, matters were thrown into confusion, and he did not choose to beard the British army with troops in such a situation. He said besides, the thing was against his own opinion.”[18] Tilghman added, “When General Lee mentioned that his orders had been disobeyed, he mentioned General Scott particularly; he said General Scott had quitted a very advantageous position without orders.” Tilghman further recalled, “General Washington answered, whatever [your] opinion might have been,” he “expected [my] orders would have been obeyed,” and then rode on toward the rear of the retreating troops, leaving a dazed Lee behind.[19]

John Brooks, temporary adjutant general for Lee’s division, was also at the side of the two generals and had similar recollections to those of Tilghman. He described the commander-in-chief as speaking in a tone of “considerable warmth.”[20] James McHenry, an aide to Washington, testified at Lee’s court-martial trial that Washington twice asked Lee why he was retreating, mentioning that Lee’s replies seemed confused and hesitant and Lee himself was embarrassed.[21] Another of Washington’s aides, Richard Kidder Meade, and one of Lee’s aides, John Mercer, both testified at the trial about the meeting, saying nothing inconsistent with these prior recollections.[22]

The two most detailed recollections are by Tilghman and, in his closing statement at his court-martial, Charles Lee himself. As did Tilghman, Lee said he specifically mentioned Scott’s withdrawing without orders.[23]

On the one hand, Lee had no time to properly explain his detachment’s predicament and Washington lacked time to use courtesies. On the other hand, Washington fumed with anger, initially at the unexpected retreat. He became more heated at Lee’s insolence in the midst of battle raising with him that he never supported the attack on Clinton’s rear guard in the first place. Washington’s harsh tone was, however, worse than the actual words he used with Lee.

Robert Harrison, returning from the front, repeated to Washington the remarks of several indignant regimental commanders who in the confusion of battle did not know why their regiments had been ordered to retreat. When asked by Harrison the reason for the retreat, Col. Matthias Ogden of the New Jersey Continentals, in Maxwell’s Brigade, snarled, “By God! They are flying from a shadow.”[24] Historian Theodore Thayer astutely noted of the opinions of these officers, “Here is good evidence of the fighting quality of the regimental officers, if not of their military sagacity.”[25]

Knowing Lee’s views on the fighting abilities of the Continental soldier and seeing his well-trained soldiers retreating, Washington must have thought Lee had timidly avoided contact with the enemy. Harrison added the shocking news that the British vanguard was only fifteen minutes away.[26] Washington moved forward, issuing orders to Anthony Wayne to take troops to post at the nearby Point of Woods. Finally, the commander-in-chief simmered down and asked Lee to lead the defense at the Hedgerow, which Lee had already started prior to his superior’s arrival. Lee agreed and said he would not be the last to leave the field.

Lee’s defense at the Hedgerow provided valuable time for the Continentals brought forward by Washington to organize their defenses at Perrine Hill. The fierce action at the Hedgerow also served to exhaust Clinton’s lead attacking force.[27]

Seeing Washington’s strong position on Perrine Hill, Clinton called off his attack and gave orders for his advance units to retreat. Washington responded by sending forward relatively small groups of attackers against some British troops who lingered too long close to Perrine Hill. The Americans charged and inflicted some damage before the last British units retreated to their camp. One of the longest battles of the war was over.[28]

The night after the battle, Lee wrote to his ally in Congress, Richard Henry Lee, a relatively accurate account of the battle. The beleaguered Lee insisted he had been forced to retreat since his detachment had been “outnumbered,” with the British cavalry numerous times on the verge of “turning completely our flanks.” Had he not retreated in the face of Clinton’s superior forces, the “army and perhaps America, would have been ruined.” Moreover, his troops conducted the retreat with “great honor” and “coolness.” “Not a man or officer hastened his step, but one regiment regularly filed off from the front to the rear of the other.” But rather than receiving deserved laurels, “the thanks I received from his Excellency were of a singular nature.”[29]

Lee in particular simmered from what he considered Washington’s ill treatment of him on the battlefield. The commander in chief, during their first meeting in the battle, had upbraided him in front of fellow-officers as if he was some tyro of a general. Lee later admitted, “I confess I was disconcerted, astonished and confounded by the words and the manner in which his Excellency accosted me.”[30] It is easy to imagine Lee, in a local tavern or around a campfire, railing about his plight before a small crowd of sympathetic aides and other admirers.

Had Lee met privately with Washington and addressed these matters face-to-face, the two men likely would have ironed out their differences. Lee could have offered a full explanation of the day’s events, swallowed his pride, and allowed the matter to drop. The fact was, at their first meeting on the battlefield, both men misunderstood the situation. Washington did not know that Lee had received bad intelligence, that some of his officers had retreated without orders, and that his force faced Clinton’s entire first division, not just a relatively small rear guard. In turn, Lee later learned that Washington, prior to their first meeting during the battle, had seen for himself elements of Lee’s detachment that appeared to be in a disorganized state and without instructions on where to march. Lee appreciated how his commander must have felt at that time. He had also failed to keep his commander properly informed of his retreat. If he had met with Washington, Lee could have explained that the bulk of his troops remained in cohesive units.

Perhaps Washington himself privately admitted he had let his temper on the battlefield get out of control without knowing all the facts. But the proud Virginian refused to call Lee to his tent and admit it. Lee also refused to come to Washington to explain his battlefield conduct.

Lee could not let the matter drop. He decided to send his commander a strong letter complaining of the “use of so very singular expressions as you did on my coming up to the ground where you had taken post.”[31] This first letter was also replete with threats and insults, despite his knowing it would likely be made public. He followed this letter up with two more insulting letters to Washington. In doing so, Lee repeated his penchant for impulsive conduct. It was a foolish and grave error he would soon—and long—come to regret. It ultimately led to his court martial and suspension from the army.

Revealingly, Lee never claimed in these letters or otherwise during his lifetime that Washington swore at him. Indeed, in his closing statement at his court-martial, Lee admitted that “the manner” in which Washington “expressed” his words to Lee “was much stronger and more severe than the expressions themselves.”[32] Lee’s best biographer, John R. Alden, wrote of Lafayette’s story, “It is certain Lee never would have permitted any man to use such language toward him without demanding an apology or satisfaction on the dueling ground; and there is not record showing he demanded that Washington retract a personal insult.”[33]

Moreover, Washington’s response to Lee’s initial letter does not indicate that he swore at Lee. Washington wrote, “I am not conscious of having made use of any very singular expressions at the time of my meeting with you, as you intimate. What I recollect to have said was dictated by duty and warranted by the occasion.”[34]

The sharp words exchanged by the Continental Army’s two top commanders on the field of battle at Monmouth Court House had fateful consequences for Lee. But the view that Washington swore at Lee during the battle is likely wrong and needs to change. The popular view of Lee failing to achieve a victory that was in his grasp at the battle of Monmouth Court House overall needs to change as well. Sometimes retreat is the best course of action. Fortunately, the Continental force was in the hands of an experienced general who, to his mortification, concluded that retreat was advisable, if not mandated, by the circumstances. In retreating, Lee may have saved the Continental Army.

[1]For a complete discussion, see Christian McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis: The Outrageous Treason and Unfair Court-Martial of Major General Charles Lee during the Revolutionary War (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2020).

[2]Quoted in George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections of Private Memoirs of Washington (New York, NY: Derby & Jackson, 1860), 413-14.

[3]Mary Stockwell, Unlikely General: “Mad” Anthony Wayne and the Battle for America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 19.

[4]George F. Scheer and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels and Redcoats (Cleveland, OH: The World Publishing Company, 1957), 330.

[5]Harry Ward, Charles Scott and the “Spirit of ’76” (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1988), 50, 52.

[6]Henry B. Dawson, Battles of the United States by Sea and Land, Embracing Those of the Revolutionary and Indian Wars, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War, with Important Official Documents, 2 vols. (New York, NY: Johnson, Fry & Company, 1858), 1:408. Historian J. L. Bell also found that Dawson’s version is the first time that Lafayette’s story appeared in a publication. See J. L. Bell, “Charles Lee a ‘Damn’d Poltroon’?,” Boston 1775 blog, November 20, 2010, boston1775.blogspot.com/2010/11/charles-lee-damned-poltroon.html. Bell adds, “Dawson cited that conversation without specifying how he came to know about it. Tompkins died in 1825. Dawson was born in Britain in 1821 and arrived in New York in 1834. So there must have been some intervening figures.” None of the early histories of the Revolutionary War claim that Washington swore. Interestingly, Benson Lossing, in his history of the Revolutionary War published in 1850, did not bring up the story, despite his penchant for including myths in his accounts of the war’s battles. Rather, Lossing wrote that Lee was “stung, not so much by these words as by the manner of Washington.” Benson J. Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution, 2 vols. (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1860) (originally published in 1850), 2:153.

[7]Lafayette’s Memoir of 1779, in Stanley J. Idzerda, ed., Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790, 5 vols. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977-83), 2:11.

[9]Mark Edward Lender and Garry Wheeler Stone, Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 290.

[10]James McHenry testimony, in Charles Lee, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, Held at Brunswick, in the State of New-Jersey, by Order of His Excellency General Washington, Commander in Chief of the Army of the United States of America, for the Trial of Major General Lee, July 4, 1778, Major General Lord Stirling, President (“Lee Court-Martial”), in The Lee Papers, 1754-1811, in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Years 1871-1874, 4 vols. (New-York Historical Society, 1872-75) (“Lee Papers”), 3:78.

[11]Robert Harrison testimony, in ibid., 72; Tench Tilghman testimony, in ibid., 79-80.

[12]Robert Harrison testimony, in ibid., 72.

[13]John Fitzgerald testimony, in ibid., 68.

[14]Tench Tilghman testimony, in ibid., 80-81.

[15]John Brooks testimony, in ibid., 147.

[16]Charles Lee closing statement, in ibid., 191.

[18]Tench Tilghman testimony, in ibid., 80-81.

[20]John Brooks testimony, in ibid., 147.

[21]James McHenry testimony, in ibid., 78.

[22]Richard Kidder Meade testimony, in ibid., 64, and John Mercer testimony in ibid., 112.

[23]Charles Lee closing statement, in ibid., 191.

[24]Robert Harrison testimony, in ibid., 73; Tench Tilghman testimony, in ibid., 80.

[25]Theodore Thayer, The Making of a Scapegoat: Washington and Lee at Monmouth (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1976), 52.

[26]Tench Tilghman testimony, Lee Court-Martial, in Lee Papers, 3:81.

[27]See McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis, 152.

[29]Charles Lee to Richard Henry Lee, June 28 (possibly 29), 1778, in Lee Papers, 2:430.

[30]Charles Lee closing statement, Lee Court-Martial, in ibid., 3:191.

[31]Charles Lee to George Washington, July 1 [should be June 30], 1778, in Dorotthy Twohig, Philander D. Chase, Theodore J. Crackel, W. W. Abbot, and Edward G. Lengel, eds., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 24 vols. (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1985-2016), 15:594-95.

[32]Charles Lee closing statement, Lee Court-Martial, in Lee Papers, 3:191.

[33]John R. Alden, General Charles Lee, Traitor or Patriot? (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1951), 343n29.

[34]Washington to Charles Lee, June 30, 1778, in Twohig et al., Papers of George Washington 15:595.

12 Comments

Great article, great insight, great research. I’m sure you will get plenty of people who fight you on this because they hate to lose a “funny” story and long accepted story about Washington. From all my study of Washington (and I’ve done a fair bit) this seems much more consistent with his character.

Thank you for presenting this information.

Thanks Dan! I agree based on his personality, though Washington was known to lose his temper (as he did here). Best, Christian

Good read. Great points! Outstanding job!

Thanks Greg! I appreciate it. Christian

Excellent article and and example of examination/use of primary sources to prove and sort out a controversial issue. Well done!

Thank you! As you point out, working with primary sources is crucial.

Wonderful history, thank you. Regarding cursing, it seems clear that Washington was badly tempted to do so—yet maintained himself. That is indeed monumental self control. Of more interest to me is how you handle a subordinate such as Lee. It is clear Lee didn’t feel the necessity to maintain control over his troops when their battlefield actions justified his personal judgement. Today we would call that passive-aggressive behavior and there is zero tolerance for that in the military. It be a bitter personal pill to swallow but necessary to command and control. It can also be a valuable lesson.

As an ROTC cadet, during a mapping exercise I decided to attack an enemy unit when I was a Cavalry platoon leader in a defensive posture. I lost the dice roll, incurred casualties and earned the ROTC Lt. Colonel’s wrath. He did not endeavor to match Washington restraint! LOL

Excellent article and very well researched!

Two things I’ve always considered about “the exchange” and the whole lost moment at Monmouth.

1. By June 1778, Washington was well aware of the rumors within the officer corps questioning his judgment and ability as commander in chief, as were his most trusted lieutenants. The Conway Cabal had been exposed by Lord Stirling and those who were among the whispering few were in clean up mode. Was Lee among the most animated in his attacks against Washington? Absolutely, and we find out much later he was feeding information to the British while in captivity. Lee had never gotten over that he was not commander in chief nor did he forgive Washington for losing New York in 1776.

2. At the war council on June 24, 1778, we know Lee was the most vocal against sending a vanguard force to prod and attack the rearguard of the British caravan. Recall, when Lee declined this command, it surprised Washington. The command was then given to Lafayette, whose movements then in turn surprised Lee who came to realize this important maneuver belonged to someone of his seniority. Only after Lafayette was in motion did Lee confront Washington and ask that the vanguard be put in his command. And critically, just after midnight on the early morning of June 28, Washington met Lee to give him instructions on the attack. Apparently the meeting did not go well, and half way back to camp, Washington sent a rider to Lee to make sure he understood the instructions precisely. So, there was already mistrust and doubt with Washington upon Lee’s ability to execute the plan.

Combine this with Lafayette’s demotion, who at this time was much more popular among the senior officer corps than Lee was, and the mismanagement of the orders by Scott and Maxwell under Lee on a day when the temperature was over 100 degrees, you can see how things went down the way they did. In the end, whatever was said or not said, Lee buried himself with his letter to Washington and did nothing to repair the resentment most in the senior office corps felt towards him. One thing is clear, after Lee’s departure, Washington’s stature as commander in chief was never challenged again, which as others have written, is perhaps the real victory of the Battle of Monmouth.

Well said Adam. I cover this ground in my George Washington’s Nemesis book. I also argue that Washington lost his cool on this occasion. I guess he was not perfect (but darn close!).

How can we break this down to share with a middle school class? There are valuable lessons of reliability and primary sources here.

You could stop at “Washington’s harsh tone was, however, worse than the actual words he used with Lee.” But don’t include any swear words in your presentation!

I should have added in the article the irony that the soldiers Washington saw streaming away from the front were those of Generals Charles Scott and William Maxwell, who retreated without orders and never informed Lee of their retreats, which in turn was the major factor forcing Lee to retreat.

Excellent research and a detailed analysis. I lived nearby the Battlefield for nearly 40 years. Retelling the history with emphasis on the people who lived a life changing reality has given substance with your well defined research.