Part of the highly revisionist history of the American Revolution that developed in nineteenth century was an apparent obsession with identifying individual sharpshooter heroes who had brought down key individuals during the war’s important battles. Never mind that no one made any such claims when the events actually occurred, no forensic techniques existed to analyze such things, and that bullets flew thickly from many directions during most of these battles; for some reason it was decided that THE person who fired THE fatal shot could be identified. By about 1850, without any direct evidence whatsoever, it was widely accepted that Timothy Murphy had shot General Fraser at Saratoga, and that Salem Poor (or was it Peter Salem) shot Major Pitcairn at Bunker Hill. In both cases the writings and recollections of participants in the battle contradict these legends. People seemed to be satisfied that in the confusion of battle, the well-known personalities could be hit only by careful, deliberate snipers rather than by chance in a hail of flying lead.

A late-comer to this list of folklore heroes was Hans Boyer, the supposed assailant of Gen. James Agnew at the battle of Germantown on October 4, 1777. Agnew was not a major player in the battle, arriving on the scene towards the end of the day’s confused and intense fighting, but he was a British general nonetheless. Boyer was far less distinguished. He was not even a soldier. The story is that he was a Germantown resident who hid behind a churchyard wall with his own gun, and shot General Agnew as he rode by. The earliest account I was able to find is from 1828:

Gen. Agnew rode on at the head of his men, and when he came as far as the wall of the Menonist grave yard, he was then shot by Hans P. Boyer who lay in ambush, and took deliberate aim at his star on the breast.[1]

Although this account dates from only fifty years after the event, when many participants were still alive, it contains details that draw suspicion. Foremost is that General Agnew had no title by which to wear a “star on his breast.” Although a long-serving officer, he held a permanent rank of lieutenant-colonel and was breveted a brigadier general only for the American war; the star that appears on portraits of some British generals denotes membership in the Order of Bath, an honor never bestowed on Agnew.[2]

That could be a fanciful detail of an otherwise-true tale, but some retellings later in the nineteenth century and early in the twentieth indicate that the Hans Boyer story was looked upon with skepticism:

It was from behind a wall which separated the Mennonite burying-ground from the street that the British General Agnew was fired upon while at the head of a column of his soldiers and mortally wounded, during the Revolutionary War. The name of the perpetrator of the deed is carefully guarded to this day by the only person who knows the truth. Hans Boyer, a half-witted fellow of that day, claimed the credit of the deed, but it is said to have not rightfully belonged to him.[3]

Boyer was the hero of his own story, and was evidently a miserable, boasting fellow. He said that he was concealed near an old wall of the Mennonist church on Main street, and when he saw Agnew coming “he took deliberate aim at the bright star on his breast and fired.” … Boyer in time came to the Germantown almshouse, and was supported at the public expense for years – a privilege which he took care to insist that he was entitled to, as he was one who had fought for his country.[4]

In 1770 the present stone church was erected. It was from behind a stone wall in front of this church that General Agnew was fired upon and mortally wounded as he was riding at the head of the British troops on that memorable fourth of October, 1777. This deed was always claimed by a half-witted fellow, Hans Boyer, who died in the Germantown Poor House.[5]

Somewhere along the line, though, the skepticism about the Boyer story vanished. Most accounts of the battle of Germantown from the second half of the twentieth century right up to the present day conveniently omit that Boyer was “a miserable, boasting fellow” and “half-witted,” instead giving simplified statements like this one:

General Agnew was killed by a civilian sharpshooter named Hans Boyer.[6]

What all of these writers overlook is that there was a witness to General Agnew’s death, and a very credible one at that. Alexander Andrew was Agnew’s young servant, a soldier who had enlisted in Agnew’s regiment in 1772. Agnew took Andrew as his personal servant when the regiment embarked for America in May 1775, and was “the only one he would ever have to wait on him both in public and private, at home and abroad.”[7] Like many soldier servants, Andrew hoped to remain in his master’s employ after the general retired, enjoying the benefits of life in a gentleman’s household. The battle of Germantown put an end to that ambition, but the aspiring Andrew decided to pursue another avenue. On March 8, 1778, he wrote a long letter to the late general’s wife, expressing his devotion to him in flattering terms and also unsubtly seeking her patronage. He also described to her the events that transpired at “that unfortunate place called Germantown, the 4th of October being the particular and fatal day of which your ladyship has cause to remember and I have much reason to regret”:

Being between the hours of 9 and 12, as the brigade was following the 3d in an oblique advancing line, the general, with the piquet at their head, entered the town, hurried down the street to the left, but he had not rode above 20 or 30 yards, which was the top of a little rising ground, when a party of the enemy, about 100, rushed out from behind a house about 500 yards in front, the general being then in the street, and even in front of the piquet, and all alone, only me, he wheeled round, and, putting spurs to his horse, and calling to me, he received a whole volley from the enemy. The fatal ball entered the small of his back, near the back seam of his coat, right side, and came out a little below his left breast. Another ball went through and through his right hand. I, at the same moment, received a slight wound in the side, but just got off time enough to prevent his falling, who, with the assistance of two men, took him down, carried him into a house, and laid him on a bed, sent for the doctor, who was near. When he came he could only turn his eyes, and looked steadfastly on me with seeming affection. The doctor and Major Leslie just came in time enough to see him depart this life, which he did without the least struggle or agony, but with great composure, and calmness, and seeming satisfaction, which was about 10 or 15 minutes after he received the ball, and I believe between 10 and 11 o’clock. I then had his body brought to his former quarters, took his gold watch, his purse, in which there was four guineas and half a Johannes, which I delivered to Major Leslie as soon as he came home. I then had him genteelly laid out, and decently dressed with some of his clean and best things; had a coffin made the best the place could produce. His corpse was decently interred the next day in the church-yard, attended by a minister and the officers of the 44th regiment.[8]

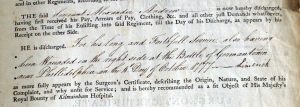

Alexander Andrew’s account makes it clear that General Agnew fell victim not to a lone sniper but to a volley of musketry. Andrew was close to the situation, wrote his account just six months after the event, and had no reason to lie about the circumstances; his goal of currying the widow’s favor did not depend upon such details. The fact that Andrew was wounded in the battle is confirmed on his discharge certificate from the army.[9]

Andrew’s letter was reprinted in one of the most widely-used references on the American Revolution, Benson J. Lossing’s The Pictorial Field-book of the Revolution, first published in 1852.[10] Why, then, has so much credibility been given to the second-hand story about a “miserable, boasting” “half-witted” civilian named Hans P. Boyer, rather than to the party of soldiers who actually brought down the British general? It appears that the quest for individual heroes overshadows the heroism of unnamed soldiers acting together. This is ironic, because the success of a military force depends not on individual, extraordinary actions but on the ability of the soldiers and officers to work together. Attempting to single out individuals causes the contributions of others to be overlooked. We should be more discerning in giving credit where it is truly due, rather than trying to create individual heroes.

[1] Samuel Hazard, ed., The Register of Pennsylvania Vol. 1 (Philadelphia: W. F., Geddes, 1828), 292.

[2] “Knights Companion of the Order of the Bath,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Knights_Companion_of_the_Order_of_the_Bath

[3] Daniel K. Cassel, History of the Mennonites (Philadelphia: Daniel K. Cassel, 1888), 113.

[4] Thompson Westcott, The Historic Mansions and Buildings of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Watler H. Barr, 1895), 278-279.

[5] Naaman Henry Keyser, “Old Historic Germantown”, The Pennsylvania-German Society Proceedings and Addresses Vol. XV (Lancaster, PA: Pennsylvania Germantown Society, 1906), 63.

[6] John B. B. Trussell, Jr., “The Battle of Germantown,” Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1974, http://web.archive.org/web/20061215001526/http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/ppet/germantown/page3.asp?secid=31 .

[7] For more on Alexander Andrew’s military career, see Don N. Hagist, British Soldiers, American War (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2012), 224-235.

[8] Alexander Andrew to Mrs. Agnew, March 8, 1778, in Ibid., 229-231.

[9] Discharged of Alexander Andrew, WO 119/1/4, British National Archives.

[10] Benson J. Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the American Revolution; or, Illustrations, by Pen and Pencil, of the History, Biography, Scenery, Relics, and Traditions of the War for Independence Vol. II.. (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852), 319. Lossing wrote, “This letter, and several written by Agnew himself to his wife at various times, are in the possession of his grandson, Henry A. Martin, M. D., of Roxbury, Massachusetts.”

4 Comments

Great examination, Don. In America’s quest for individual heroes, a “half-wit” can still grow to become a patriotic sharpshooter. [Sigh] Add Boyer to the list of Murphy and Poor (or Salem).

As one who has researched the shooting of a British general (see “Infamous Skulkers: The Shooting of Brigadier General Patrick Gordon”) I always enjoy reading about similar incidents and comparing them to the killing of Gordon. Thanks for posting this article.

The point about creating individual heroes is one many folks miss. American historiography in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had a different drive to it than today and two related elements of that process apply to this article. For one, the story mattered more than the facts–in this case, Hans Boyer’s story. Our modern obsession with detailed accuracy did not appear until the second half of the twentieth century. For the second element, historiography centered on the top down, great men, great events approach rather than the grass roots, bottom up method now favored. But, America did not have a centuries-old past with droves of legends as did the European countries. America had no ancient heroes to put on pedestals and on which to build its history and culture. Lacking these important elements, historians set out to create those heroes and latched onto any story that provided the basis for one. As a result, we end up with heroes–right or wrong–like Hans Boyer and Tim Murphy and Ethan Allen (I threw that one in ’cause I live in Vermont).

True, Mike. Nineteenth century revisionist efforts took off immediately following the close of the War of 1812. That conflict was founded on American insecurity, feeling as though it was being rejected and ignored by the European powers, and which then led to it incredible declaration of war against Britain while in a bankrupt condition. However, with the war’s end (which finished status quo ante bellum and no “winner” per se) the Era of Good Feelings broke out and America entered the nationalism craze by declaring its heroes.

That also happened here in Vermont, a state similarly dealing with an identity crisis, as it flailed around trying to find a “hero,” settling as we know on Allen, an individual with a ton of baggage.

I’ve read accounts that Brig. Gen. James T. Agnew was shot next to the Old Concord school from which there is a wall separating the school and the upper burial ground, which makes sense. At the Mennonite meeting house out front is a plaque which states General Agnew was shot and killed near here. The Concord school is at 6300 Germantown Ave. and the upper burial ground next door is separated from it by a wall.