The British government’s policies toward the American colonies in the 1760s and 1770s were controversial in Great Britain; some people favored the government’s actions while others were sympathetic to the grievances of the colonists, with a wide range of opinions in between. When war broke out, the controversy continued, with some believing in reconciliation, some championing unrestrained use of military force, others still seeing American independence as the best outcome. The diversity of opinions made for no shortage of editorial content in the nation’s media, and in this era the primary editorial medium was print. Newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, broadsides, cartoon prints and other ephemera broadcast opinions in London, Edinburgh, Dublin and most other cities and large towns across the British Isles.

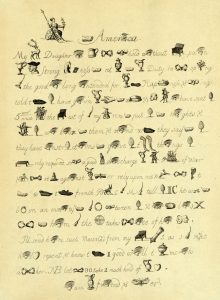

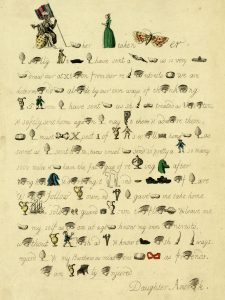

Authors of political tracts didn’t rely solely on prose. Songs, poems, plays and pictures were all used to promote political opinions, often relying on satire and other entertainment techniques to make the message attractive to eager consumers. One of the more unusual techniques was the rebus, a message written using a combination of letters and pictures. The reader had to decipher the message by interpreting the pictures and then combining them with the letters to form words. As such, the rebus provided satisfying entertainment to convey its message. Two examples, published in London in 1778 and currently held by the Library of Congress, appear below. The first is a letter from Britannia imploring her rebellious daughter America to stop courting a French suitor. In the opening line, Britannia is rendered as the Roman goddess of that name, a toe is used to phonetically indicate “to,” and an eye forms the third syllable in “America.” So the letter begins, Britannia to America. The next line reads, “My dear Daughter I can not behold without great pain your headstrong backwardness…” (using images of a deer, eye, can, knot, bee, grate, ewer, head, etc.). Try to puzzle out the rest, and the amusing message in the second rebus!

One thought on “The Revolutionary Rebus: A Coded Message Not for Spies”

What a fascinating piece, and I never saw it in five years apparently. This actually could open up an whole new conversation about 18th-century dialect. If we accept the understood “A” at the end of a word sounding like “ay” coupled with an eye in the acrostic for the I in America the word becomes “Amer-eye-Kay.” Not to mention the word “to” pronounced as “toe.”