Following the Battle of Monmouth in late 1778, the traditional narrative of the American Revolution becomes lost for many non-specialists. With the existing dichotomy of “American Patriot” versus “British Redcoat” in popular culture, newcomers are often bewildered by the terrible brand of violent politics that so typifies the war on the frontiers of New York and Pennsylvania. From the Mohawk River Valley to the wilds of the Ohio Country, the brutal raids executed by bands of Tory militia and Allied Indian warriors were the primary threat to Continental forces throughout the west. On August 11, 1779 Colonel Daniel Brodhead, the head of the Western Department, launched an uncertain campaign against an unconventional enemy in the wilderness of the Ohio Country. After thirty-five days of long marching through terrible weather, the last vestiges of Western Seneca, or Mingo, culture lay in ruins. While the Brodhead Campaign has long been overshadowed by more notable northern operations led by Maj. Gen. John Sullivan and Brig. Gen. James Clinton, lingering questions have made Brodhead’s Campaign a curious footnote in the larger narrative of the American Revolution. Amongst the most unique aspects of this campaign was the small yet fiery engagement that occurred some eight days into the expedition known as the “Battle of Thompson’s Island.”

Washington’s War on Iroquoia

On February 25, 1779 the Continental Congress resolved “that the representation of the circumstances on the western frontiers…be transmitted to the commander in chief, who is directed to take effectual measures for the protection of the inhabitants, and chastisement of the savages.”[1]

For General George Washington the year 1779 would be one of great consequence as he received congressional authorization to orchestrate what would be perhaps his most effective campaign of the American Revolution: the destruction of Iroquoia. From his own experiences in the Seven Years’ War, Washington understood that the methodology of Indian warfare relied completely on quick, unexpected raids often great distances from their home villages. For this reason it was essential for those far-ranging warriors to only strike seasonally, always returning home to hunt while their families harvested grain for the harsh winter months.

While a stalemate had developed in the northern theater of operations between American and British forces, the lull in the action allowed Washington to focus his efforts in other places. Since the start of the conflict the Iroquois had feigned neutrality while leaning toward King George III, and once they had actually declared their intentions the American frontier descended into a familiar chaos of violence and terror. Indian forces under stand-out warriors such as Joseph Brant suddenly paired with Loyalist Rangers like John Butler to strike fear into Patriot communities across New York and Pennsylvania. In the previous year alone major raids by these joint Indian-Loyalist militia at Cherry Valley and Wyoming Valley had brought a new element of ferocity and partisanship to the conflict that had been unseen to that point. Worse yet was the very clear realization that unless Washington made a direct and concerted effort to curtail these tactics, they were likely to worsen.

At the heart of his strategy was the destruction of Iroquois villages, not the Iroquois themselves. Washington wrote in 1779 that “the object of this expedition will be effectually to chastise and intimidate the hostile nations, to countenance and encourage the friendly ones, and to relieve our frontiers from the depredations to which they would otherwise be exposed…it is proposed to carry the war into the heart of the country of the Six Nations, to cut off their settlements, destroy their next year’s crops, and do them every other mischief, which time and circumstances will permit.”[2]

To this end he was correct, but destruction of property was merely the beginning. Along with utterly disabling the Iroquois way of life by reducing their ancestral homelands to ashes, Washington also understood that their tenuous alliance with the Crown on the frontier could also be exploited if properly managed. By eliminating the sustainability of the Six Nations, Washington further speculated that the bulk of the subsequent refugee crisis would be directed at the already undersupplied British posts nearby, specifically Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario. He solicited advice carefully, and his trusted subordinate Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene specifically stated that the ideal time to strike these villages would be during their most vulnerable months: “To scourge the Indians properly there should be considerable bodys of men march into their Country by different routes and at a season when their Corn is about half grown. The month of June will be the most proper Time.” [3]

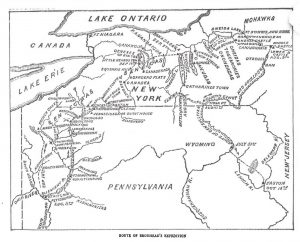

In January of 1779, a month before receiving congressional authorization, Washington had already sketched out a rough plan of attack for his “chastisement” of the natives and selected his primary commanders. Forces under the command of Maj. Gen. John Sullivan would move north along the Susquehanna River until reaching the village at Tioga. At that location Sullivan would link up with Brig. Gen. James Clinton moving westward from Canajoharie through the Mohawk River Valley. When these forces combined the general hoped that they could next focus their efforts on capturing the Loyalist stronghold of Fort Niagara granting the Continental Army a more permanent foothold on Lake Ontario. The third portion of Washington’s campaign, often overlooked, was launched from the Western Department at Fort Pitt.

Fear and Loathing in Pittsburgh

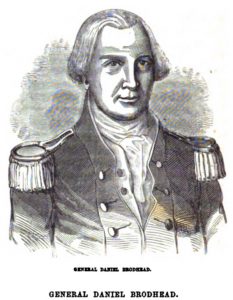

Washington’s strategy involved an operation from Pittsburgh from its inception, though its aims shifted dramatically through the winter and spring of 1779. Originally working exclusively with Brig. Gen. Lachlan McIntosh, Washington first envisioned soldiers marching out of the Western Department headquarters for a strike on Fort Detroit. By March of 1779 that objective proved to be untenable and worse yet McIntosh had to be removed from his post due to a lack of respect and control in the region. His replacement, Col. Daniel Brodhead, was an ally of Washington’s from their harsh winter at Valley Forge. A severe man with strong Pennsylvania ties, Brodhead was a dutiful officer who had Washington’s full faith. “From my opinion of your Abilities, your former acquaintance with the back Country, and the knowledge you must have acquired upon this last tour of duty, I have appointed you to the command in preference to a stranger, who would not have time to gain the necessary information between that of his assuming the command and the commencement of operations,” Washington penned. Brodhead was a natural choice to lead this expedition against the Seneca of the region, and from his earliest tenure at the helm of the Western Department, Washington kept him fully abreast of his expectations for the year to come.[4]

The region in which Brodhead commanded was an unruly one. The residents of Pittsburgh were strongly against the channels of authority that emanated out of Fort Pitt, and deep resentment soured relations between the populace and their local commandant. Fifteen years prior in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War Colonel Henry Bouquet, a fellow commandant of the post, referred to Pittsburgh as “a colony sprung from Hell,” and in Brodhead’s time not much had changed in that regard. The Ohio country was a wild and untamed expanse, and successful movement through such a treacherous landscape was almost wholly dependent on water travel. What roads and passages did exist were typically constructed as lines of communications between fortifications or were long-travelled Indian trails, and for Brodhead to launch a successful campaign against the Iroquois settlers in the region he would need to take full advantage of the natural superhighways that Mother Nature provided. His primary route of passage into Seneca country was to be the Allegheny River stretching some 325 miles northward. The path of the river was well known; it flowed southward from Northern Pennsylvania after turning briefly into Western New York. Along its course were countless native villages of varying importance that had been frequented by Europeans since their explorations by agents of New France decades earlier. Washington himself travelled throughout the region on several occasions during the Seven Years’ War, and he stressed to Brodhead the importance of fortifying key locations along the way to ensure that he and his men were never isolated in an unforgiving country.

Foremost in Washington’s mind was the creation of a new post twenty miles north of Pittsburgh at the former Western Delaware village of Kittanning. While it was long vacant in Brodhead’s time, Kittanning developed a reputation two decades earlier as a locus of French-allied Ohio Indians on the frontier. It was at this site that dozens of white captives were held, and that Tewea (aka Captain Jacobs) kept his family home. With a $700 bounty placed on his head by the colony of Pennsylvania, Tewea was considered the face of the particular brand of terror implemented by the Ohioans throughout the Seven Years’ War. In an effort to quash the Western Delaware threat the colonial legislature commissioned John Armstrong to raid the location in 1756, and though the battle that ensued was largely a stalemate, the village of Kittanning was all but destroyed. Now, twenty-three years later, Brodhead would effectively reclaim the site by ordering the construction of a new forward operating base atop its remains. It would be dubbed Fort Armstrong. With Fort Pitt serving as a bastion of safety in the uncertain world of the Ohio Country and the headquarters of the Western Department, Fort Armstrong would be yet another satellite post supporting the critical Patriot military presence at Pittsburgh.

For Brodhead the preparations for an expedition against the Mingo were fraught with difficulties. As was often the case on the frontiers, Brodhead had to contend with an unruly populace and a constant lack of supplies. Aside from the tangible dangers of engaging his native foes in their own territory, these logistical difficulties alone would be enough to bring the entire campaign to a screeching halt. Regardless of his tribulations, Brodhead remained anxious to deliver an assault into the Allegheny River Valley, but his commanding officer was more apprehensive. On April 21, Washington wrote to Brodhead that the entire expedition was to be cancelled immediately; whatever resources the colonel had at his disposal were to be used to supply Fort Pitt and its dependent posts. Washington penned, “I have relinquished the idea of attempting a cooperation between the troops at Fort Pitt and the bodies moving from other quarters against the six nations. The difficulty of providing supplies in time…are principle motives for declining of it. The danger to which the frontier would be exposed…is an additional though a less powerful reason.”[5]

In spite of Washington’s wavering, Brodhead never lost his zeal for the campaign. In the truest fashion of a frontier commandant, he quickly realized the intense resentment that the settlers in and around the forks of the Ohio had for their native neighbors. On May 26 in a letter to Nathanael Greene he reiterated his enthusiasm for the campaign: “I should be much happier could I but act on the offensive…and give the Senecas a complete flogging.”[6]

Brodhead’s March

Throughout the month of May, with Sullivan and Clinton’s campaigns now a certainty, Daniel Brodhead operated with an audacious amount of impunity at Pittsburgh. Since receiving Washington’s cancellation of his proposed march, Brodhead began to utilize the services of some of the most respected and hardened frontiersmen available to keep local British allied Indians at bay. Samuel Brady, one of the most revered Indian fighters in the west, led members of the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment wearing full native war paint in short raids against local Mingo warrior bands. Although these strategic forays were effective at creating an expanded zone of safe operation for future campaigns, they also served as a clear warning to the already fearful Western Seneca that danger was looming out of Fort Pitt. Combined with Sullivan’s already damaging efforts, the populations of Indian villages throughout the Allegheny River Valley began to flee en masse. Ever the faithful subordinate and only slightly boastful, Brodhead wrote to Washington informing him of the effectiveness of these actions.

On July 21, George Washington responded to Col. Brodhead with welcome news: the Allegheny River Valley campaign which gave “consent to an expedition against the mingoes” was approved. Washington explained that given the scale of the Sullivan and Clinton campaigns in New York, Brodhead’s action would serve as a spectacular “diversion” in support. The notion of striking Forts Detroit or Niagara were long ago deemed unsound, but Brodhead’s confidence and regular updates convinced Washington that timely action against potential threats in the Ohio Country would be a tremendous benefit to his overall demolition of the Iroquois heartland.[7]

On August 11 Col. Brodhead began his march northward along the Allegheny River accompanied by members of the 8th Pennsylvania and 9th Virginia. Alongside them were Rawlings’ Maryland Rifle Corps, a host of American allied Delaware warriors, and a contingent for moving supplies and foodstuffs. In total the campaign collected over 700 men and created a stark image of the Ohio frontier in a microcosm. While the men marched along the shores of the river itself, the force’s supplies (approximately thirty days’ worth) would be either floated alongside them or carried by the more than 400 packhorses that followed behind. The march that proceeded was arduous, and after arriving at the newly constructed Fort Armstrong the army replenished whatever supplies it could. After leaving Kittanning, Brodhead’s army travelled as far north as Mahoning, a vacant Indian village, and sat for four days in the midst of a torrential downpour that scattered their supplies and animals. When the weather cleared the colonel made a bold and calculated decision. By following the narrow channel of the river valley Brodhead was given a direct vein into the heart of the Seneca homeland, but by temporarily abandoning that avenue and following known Indian paths he could easily save a day’s march and, more importantly, precious supplies.

While this decision seemed prudent at the time, the realities of wilderness maneuvering soon took its toll on his men. In an anonymous letter published in the Maryland Journal, a member of the expedition recounted “we proceeded by a blind path…thro’ a country almost impassable, by reason of the stupendous heights and frightful declivities, with a continued range of craggy hills, overspread with fallen timber, thorns, and underwood…whose deep impenetrable gloom has always been impervious to the piercing rays of the warmest sun.” The path was a well-established route to the Delaware village of Cushcushing. Upon reaching the abandoned village and once again locating the Allegheny, Brodhead instructed his men to cross the river and proceed north. It was at this time that the men undoubtedly began to stiffen their focus as the tightly clustered villages of Buckaloons and Conewago were only a day’s march away.[8]

The Battle of Thompson’s Island

Following their rediscovery of the Allegheny River, Brodhead’s men continued their northward trek toward Seneca country. By the time they moved within four miles of the Delaware village of Buckaloons at the mouth of Brokenstraw Creek, the American line had thinned out to a long defile stretching nearly a mile. In the heart of the modern Allegheny National Forest, the Allegheny River Valley becomes a narrow causeway surrounded on both sides by tall, jagged peaks. As Brodhead’s column marched they had little option but to press on in a narrow line; even the most inexperienced of the militia knew that if attacked, retreat was nearly impossible. At the vanguard of Brodhead’s force was a collection of fifteen Continental regulars of the 8th Pennsylvania led by Lieutenant John Hardin and eight allied Delaware warriors. For much of the campaign thus far Hardin had been the eyes and ears of Brodhead’s force as it snaked through the narrows. Sometime around 10 am on August 18 or 19 the advanced guard encountered a southward moving hunting party of Ohioan warriors primarily comprised of Mingo (Western Seneca) warriors. Because of the inflexible nature of the terrain, the two forces could not have avoided one another. Estimating the number of warriors to be “thirty or forty,” Brodhead wrote that firing began almost immediately following initial contact. Regarding the details of the battle the colonel is silent, likely because other eyewitness reports claim that the main army was as far as a mile behind the forward guard, and the action had subsided by the time that they arrived.[9]

Although the native warriors “immediately stripped themselves and prepared for action,” neither side likely had any idea that the other was so close by. According to the anonymous writer’s eyewitness account Hardin burst into action by deploying his men “in a semi-circular form, and began the attack with such irresistible fury, tomahawk in hand, that the savages could not long sustain the charge, but fled with the utmost horror and precipitation.”[10]

Identifying the precious “first contact” in an engagement is of the utmost importance. Jesse Ellis, a captain marching with Brodhead, adds more essential details. He wrote that Joseph Nicholson, a well-respected pilot and Indian interpreter, was among the first Americans to spot the warrior party. He instructed the remainder of Hardin’s vanguard to take cover while he “hallowed” them to parlay. The Americans “squatted in weeds & in a gut putting into the river.” Ellis continues by stating that “while Nicholson, at some distance off, was talking with them, some of the men peeping up were discovered by the Indians who quickly fired…” He claimed that Nicholson and the warriors both took for the trees, and “the fight lasted hotly & severely about ten minutes.”[11]

Daniel Higgins, an Irish immigrant who volunteered to serve under Brodhead after moving to Pittsburgh in 1778, also adds valuable but highly speculative details. Serving under the command of Capt. John Clark, he verifies that the warriors immediately took to the trees at the start of the battle. He continues by claiming that the Mingo were “going on an expedition against the settlements” and that they were a Delaware war party under the command of Simon Girty. These details are almost certainly erroneous, and likely fabricated out of learned prejudices from over a year of frontier life.[12]

Captain Matthew Jack, who raised and led a company of “six months men,” relates in his letters that the native band encountered on that day numbered over 100, and that after the initial clash the Americans fell back with the warriors in pursuit. He writes “they Stood but one or two fires; we killed 12 of them and the rest ran.” He adds that “4 or 5 of our men were killed or wounded.”[13]

As in any frontier engagement, the details of this clash are all varied in a number of ways. Casualty figures vary, but Brodhead’s estimates that “five of the Indians were killed and several wounded” appear to be the most accurate. Many of the eyewitnesses at the vanguard of his column claim that the Mingo fled leaving their dead behind, and multiple reports indicate that a Delaware ally of Brodhead’s was wounded in the battle. Interestingly, Brodhead records that none of his men were killed, yet Capt. Jack claims to have lost four or five comrades. Given Capt. Jack’s gross exaggeration of having battled over 100 warriors, his estimates should be taken as inflated and Brodhead’s as the most accurate.

The Battle of Thompson Island is unique in that Native descriptions remain from the battle itself. Recorded in 1850, an interview with Charles O’Bail, the son of the powerful Seneca warrior and diplomat Cornplanter, provides helpful details preserved in oral tradition. O’Bail stated that the party encountered by Brodhead was a hunting party led by “Capt. Crow” and “Red-Eye.” He recited that earlier in the day the party had been moving inland from the Allegheny to “start the deer” toward the river where other warriors awaited on the river islands nearby. It was during this effort, O’Bail claimed, that the first encounter took place. When the engagement began “Crow & two of the others took to the woods, who escaped: Red Eye & his two companions pushed off in the canoe, aiming to reach the eastern bank of the river, thinking they would be safest there.” Red Eye then took to the river island for safety, and after dodging several volleys escaped into the wilderness.[14]

A second interviewee, the Seneca chief Blacksnake, corroborated that the men were out as a hunting party and that Red Eye made a daring escape to safety. Like O’Bail, Blacksnake recalled that it was Red Eye’s testimony that survived into the 19th century. “he Saw a company of men of war, and count them, how many it was…about 500 men…he Run as fast as he could, then they put after him…but he Rather outrun them as soon as he got into their camp he told his comrate [sic] that the whites company are coming close to hand that they had Better Run soon as possible, So they start it and Run for their lives…”[15]

With consideration given to the disparities in the source material, the opportunity to study both Native and American sources for an isolated incident such as the Battle of Thompson’s Island is a rare opportunity. One certainty is that the engagement was fiery and swift, and only a momentary stumbling block of Brodhead’s greater mission.

Brodhead’s Return

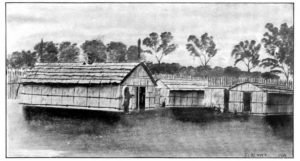

Following the chaotic skirmish at Thompson’s Island, Brodhead’s campaign continued north through the chasm until reaching the mouth of Brokenstraw Creek. At that site the Americans found the abandoned remains of the Delaware village called Buckaloons. Sensing that danger might still approach in retaliation to the previous day’s battle, Brodhead ordered the construction of a breastworks to defend against the threat; though his men toiled to meet his demands, the counterattack never came. The Americans next made their way east only to find Conewago, a much more prominent and well-known Delaware site, also vacant.

Above Conewago was the great unknown to Brodhead, and he prepared his men to march headlong into Seneca country. His primary interpreter John Montour was a man of mixed race who had been an active member of the Wyandot nation. His input had been valuable to this point, but he had no active knowledge of what lay ahead in Iroquoia. Brodhead marched his men over twenty miles as far as Yoghroonwago, a cluster of eight separate Seneca villages including 130 homes, only to find them fully vacated. Unlike the Delaware villages to the south, however, Yoghroonwago was brimming with signs of recent life including fields flush with corn and an abundance of furs. While it seemed that Conewago was discarded months earlier, whomever had been living at Yoghroonwago had only recently fled. For the next three days Brodhead ordered his men to pack as much of the stores and supplies as they could, with hopes that they could be sold for profit at Pittsburgh. Captain Jesse Ellies relates vital details: “500 acres of corn, cattle taken for beef…30 horses, 30 brass kettles…”[16]

After the successful plunder of the Seneca villages and a return south to burn Conewago and Buckaloons, Brodhead turned his men westward with hopes of returning home via the French Creek. While it appeared that he wanted to avoid backtracking, he also likely wanted to inflict more damage if possible. Brodhead next sent Capt. Matthew Jack and Capt. Samuel Brady to lead a force to the village of Mahusquechikoken which was stripped, spoiled, and likewise burned. After completing their mission, the force reunited at the mouth of the French Creek at Venango where they began their southbound descent to Pittsburgh. When they reached Fort Pitt on September 14 the settlements at Buckaloons, Conewago, Yoghroonwago, and Mahusquechikoken had all been left in flames; Brodhead’s total plunder would sell for over $30,000.[17]

The Brodhead Campaign of 1779 paled in comparison to its northern counterparts in New York and did little to bring about a satisfactory ending to the war; however its impact on the Indian landscape of the Ohio Country is undeniable. The villages of Buckaloons and Conewago were considered diplomatic staples of the region from as early as the 1740s, and throughout the Seven Years’ War they were noted population centers. The torching of those already-abandoned settlements ensured with finality that they would remain vacant. The sheer damage done combined with one of the harshest winters on record combined to effectively eliminate the ancient system of the Iroquois world. The battle site now labeled “Thompson’s Island” remains relatively unchanged since that fateful day in 1779, yet it hosts no visitors and offers no interpretation. On the whole, like the campaign to which it belonged, it has largely been relegated to obscurity in the greater Revolutionary story.

George Washington’s overall objective was “total war” on Iroquoia, and with the aid of Brodhead’s Campaign he succeeded in spectacular fashion. In Washington’s own words: “The activity, perseverance, and firmness which marked the conduct of Colonel Brodhead, and that of all of the officers and men of every description in this expedition, do them great honor, and their services entitle them to the thanks, and to this testimonial of the General’s Acknowledgment.”[18]

[1] February 25, 1779. Journals of the American Congress (Washington, D.C.: Way and Gideon, 1823), 3:212.

[2] Gen. George Washington to Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, March 6, 1779, John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. Writings of George Washington (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1936), 14:198-200.

[3] Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene to Gen. George Washington, January 5, 1779, Richard K. Showman, ed. The Papers of General Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1984), 3:144-145.

[4] Washington to Col. Daniel Brodhead, March 5, 1779, Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington, 14: 194-196.

[5] Washington to Brodhead, April 21, 1779. Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington, 14: 421.

[6] Brodhead to Greene, May 26, 1779. Showman, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 4: 81-83.

[7] Washington to Brodhead, July 13, 1779, Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington, 15: 418-419.

[8] Anonymous Letter, Maryland Journal, Oct. 26, 1779, Louise Phelps Kellogg, ed. Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio (Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1917), 56-57.

[9] Brodhead to Washington, September 16, 1779. Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 55.

[10] Anonymous Letter, Maryland Journal, Oct. 26, 1779, Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 56-57.

[11] Recollections of Capt. Jesse Ellis, undated. Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 58.

[12] Recollections of Daniel Higgins, undated. Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 59-60.

[13] Recollections of Capt. Matthew Jack, undated. Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 61.

[14] Charles O’Bail to Dr. Draper, 1850. Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 62-63.

[15] Blacksnake to Dr. Draper, 1850. Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 63-65.

[16] Ellis, undated. Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 55.

[17] Brodhead to Washington, Sept. 16, 1779. Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 55.

[18] Washington, General Orders, Oct. 18, 1779. Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington, 16: 480-481.

6 Comments

Great article! It’s nice to see someone tackle the Brodhead expedition in the western theater of Pennsylvania. You’re quite right that a lot was happening on the frontiers of New York and Pennsylvania that most locals don’t even know about.

Thanks for an interesting article. Can you describe the lead photo? As a footnote, Brodhead had few positive things to say about the command during the Battle of Brooklyn, in general, and Sullivan, in particular. Brodhead largely blamed Sullivan for the failure of the American advance guard on the left that allowed the British column to flank the American line. Having been ordered by Washington to lead a move against the western frontier, coinciding with Sullivan’s main thrust in central NY, Brodhead couldn’t help but feel he needed to come away with a notable success. It appears that he did.

From the caption, the photo appears to be taken from the site of Ft Venango at the site of French Creek and the Allegheny River, looking north up the river, with French Creek entering from the left. Brodhead avoided this site on his march north by abandoning the river trail and going overland to Lawanakaha. He returned south via Venango, where he detoured northwest up French Creek to secure it before returning to Ft Pitt.

Perhaps Mr. Crytzer will add more detail.

Thank you for this article on the pretty much forgotten war of 1779. The border warfare in New York, Pennsylvania and the West ( George Rogers Clark ) is largely forgotten compared to the major campaigns and battles of the American Revolution! I find these particular types of histories fascinating to say the least!

Thanks again.

John Pearson

Thank you for the kind words! I appreciate this chance to dialogue with such immediacy. The image posted above is indeed the site of Venango. I recommended this image because of its relation to Brodhead’s return march, but also because it gives a very strong visual representation of the Allegheny River Valley as a whole.

This sounds like it could be a fantastic historical trek, and could even be set up as a meeting engagement.