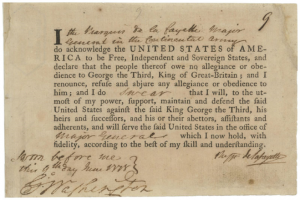

In 1775, Gilbert du Motier de Lafayette was an eighteen-year-old French soldier assigned to military maneuvers at Metz. At Metz, he attended an official dinner where the Duke of Gloucester, younger brother of England’s King George III, was expounding upon the American Revolution.[1] Amazed by what he heard, Lafayette later wrote, “My heart was enlisted, and I thought only of joining my colors to those of the revolutionaries.”[2]

When Louis XVI forbade this young French soldier to go to America, Lafayette deliberately disobeyed orders, leaving France with Baron DeKalb and a dozen friends and colleagues. They set sail from Spain in Lafayette’s ship la Victoire on April 20, 1777, reportedly heading for Santa Domingo.[3] Landing in South Carolina, they made their way 650 miles to Philadelphia, where, on July 31, Lafayette was commissioned “Major General without pay.”[4] Lafayette’s first sight of the American troops came on August 8 when George Washington reviewed the Continental army.

A month later, at the Battle of Brandywine (September 11, 1777), a bullet filled Lafayette’s boot with blood. Now twenty years old, he spent the winter with Washington’s army at Valley Forge and in late May was the hero of an action in nearby Barren Hill, Pennsylvania. Other adventures followed at Monmouth and Rhode Island in 1778. With no new military orders, coupled with unhappy news from France about the death of his tiny daughter, and the inability to recoup his investments due to la Victoire foundering off the eastern seaboard in the summer of 1777,[5] Lafayette became restless. He requested a leave of absence to briefly return to France.

Monsieur Gerard, the French minister at Philadelphia, wrote ahead to the government in Paris, “You know how little inclined I am to flattery, but I cannot resist saying that the prudent, courageous, and amiable conduct of the Marquis de Lafayette has made him the idol of the Congress, the army, and the people of America.”[6]

Upon his arrival, Lafayette’s wife, Adrienne de Noailles de Lafayette, wrote, “Monsieur de Lafayette has returned, as modest and charming as when you last saw him, his sensibility undiminished… [He] is now in the king’s disfavor and is forbidden to appear in any public place. We hope this will not last long…nor will he be able to leave for some time after the restriction ends since he must take advantage of the king’s good will when it is offered to him.”[7] Lafayette formally apologized to the king for having left France without permission,[8] and soon began lobbying him for ships and supplies for America. By March, 1779, Ben Franklin reported from Paris that Lafayette had become an excellent advocate for the American cause at the French court. The following year, the success of Lafayette’s efforts would be apparent.

On February 21, 1780, Lafayette wrote from Versailles “It seems to be settled that on March 4, I shall find a fast-sailing frigate at Rochefort ready to take me directly to Boston. It will carry neither arms nor clothing but only a few packages of presents for my division. I shall provide a list of what should be carried over with me.”[9]

About the same time, thirty-four year-old Louis de La Touche was called upon to report to the mouth of the Charente River no later than February 20 to await the specific orders regarding a mission from the Navy Minister. The aristocratic La Touche was the son of a naval officer, and a nephew of Charles de La Touche Tréville, squadron chief. The frigate at Rochefort was l’Hermione, one of the king’s best ships. The ship’s crew included a number of officers, a surgeon and a priest. About half the three hundred and thirteen working on board were sailors whose responsibilities were to maneuver the ship and man the cannons, but La Touche did not yet know what this mission would be.

March 5, 1780 was an important day for America. On that day, Louis XVI issued the orders: “Monsieur le Marquis de Lafayette will hasten to join General Washington whom he will secretly inform that the King will send at the beginning of spring, help consisting of six ships and approximately 5,000 infantrymen.”[10] A list of the ships and supplies the French contemplated sending can be found in the correspondence between Chevalier de Fleurieu and French Minister of the Navy, Gabriel de Sartine (1729-1801), dated March 5 and 6, 1780.[11]

Lafayette was now authorized to communicate to Washington that the French troops “shall be simply auxiliaries, and with this title they shall come under the orders of General Washington. The French General shall receive the orders of the American commander in chief in all things except what pertains to the internal management of his own troops…In case operations by land should not require the concert of the squadron, it will be free to cruise at such a distance from the coasts as the Commandant shall think best for doing the most harm to the enemy.”[12]

The secrecy of the mission was communicated to the commander of the navy at Rochefort who received word that the details of the mission were not to be shared. De Sartine informed ship’s captain La Touche that Lafayette was to have decent lodging on board l’Hermione and, according to strict orders from the king, was to present the list of his four officers and eight servants to La Touche. No additional passengers were to be permitted on board. The password would be “Saint Louis and Philadelphie.”[13]

In the midst of the excitement, on March 9, 1780, Rochambeau’s appointment to the American mission was announced. John Adams, from his diplomatic post in Paris, reported that Lafayette, unhappy at having been passed over for Rochambeau, made a silent statement of protest, bidding adieu to his monarch “in the Uniform of an American Major General.” Adams noted that when Lafayette appeared before Louis XVI in American attire, his uniform “attracted the Eyes of the whole court.” Adams was sure that the sword Lafayette was carrying that day was the one commissioned for him by Congress. It “is indeed a Beauty,” Adams conceded, “which Lafayette shews with great Pleasure.”[14]

Lafayette left immediately for Rochefort where l’Hermione was waiting for him in the river at Port des Barques. Final preparations took place on March 11. The four officers designated by Lafayette boarded, then a careful search of the decks was made to assure no unauthorized passengers had come on the ship. L’Hermione finally set sail for America on the night of March 14 or 15.[15]

Lafayette’s autobiography states, “This expedition was kept very secret; Lafayette had preceded it on board the French frigate the Hermione; he arrived at Boston before the Americans and English had the least knowledge of that auxiliary reinforcement.”[16]

Lafayette was now twenty-two years old, a husband and father of two surviving children. Captain Latouche[17] wrote de Sartine: “I will have for M. le Marquis de La Fayette all the consideration and attention not only prescribed in your orders, but those that my heart dictates for a man whose actions have inspired in me a great desire to make his acquaintance….I will offer him the choice of my room or the one next to mine which previously served as Council Room.”[18]

On March 20, stormy seas and wind resulted in damage that forced l’Hermione back toward Ile d’Aix. A small boat was launched to retrieve a replacement part. La Touche took the opportunity to send word of Lafayette’s good health and well-being on board l’Hermione. The repair was made, but now l’Hermione was further delayed by lack of wind. Finally, once at sea, l’Hermione had an exchange of cannon fire with a British ship. On April 10, a sailor died from a fever similar to typhoid. A few days later, a repair had to be made in the uppermost section of a mast and a malfunction in a compass caused frustration. Finally, the American coast came into view on Thursday, April 27, and by 2:00 in the afternoon l’Hermione found shelter in the small port of Marblehead, sixteen miles from Boston. La Touche noted that “Brigadier General Glover came on board to see Monsieur the Marquis de La Fayette.”[19]

Lafayette wasted little time in sending a communique to George Washington, alluding to Louis XVI’s still-secret news:

“Here I am, My dear General, and in the Mist of the joy I feel in finding Myself again one of your loving Soldiers I take But the time of telling you that I Came from france on Board of a fregatt Which the king Gave me for my passage–I have affairs of the utmost importance that I should at first Communicate to You alone…and do Assure You A Great public Good May derive from it.”[20]

At 2:30 in the afternoon of April 28, 1780, l’Hermione, with French flag flying high, arrived in the port of Boston and saluted the American flag that was displayed at the fort on Castle Island with thirteen cannon shots. Word that the ship had been sighted spread through the city, and the wharves were lined with people. As Lafayette left the ship, he was saluted by La Touche and his crew.

La Touche wrote to de Sartine that day of the eventful crossing and the enthusiasm raised in Boston by the return of the young Major General. “Mr. the Marquis de La Fayette enjoyed good health throughout the crossing…He received the most distinguished honors of the people with bonfires and shouts of joy, respect no less shown by the officials of the State, their pleasure at seeing him again. On the docks the crowd demonstrated with cries of joy and musket fire. La Fayette went ashore at 1:00 stirring the level of celebratory noise even more.”[21]

The arrival of Lafayette at Boston “produced the liveliest sensation, which was entirely owing to his own popularity, for no one yet knew what he had obtained for the United States. Every person ran to the shore; he was received with the loudest acclamations, and carried in triumph to the house of Governor Hancock, from whence he set out for head-quarters.[22]

The excitement was confirmed by Abigail Adams in a May 1 letter to her husband: “Last week arrived at Boston the Marquis de la Fayette to the universal joy of all who know the Merit and Worth of that Nobleman. He was received with the ringing of Bells, firing of cannon, bon fires, etc.”[23]

Lafayette left Boston on May 2 to travel to Washington’s headquarters at Morristown, New Jersey. Festivities like those that had greeted him in Boston erupted in every town Lafayette passed through on the two hundred and fifty mile journey. “It’s to the roar of cannon that I arrive or depart; the principal residents mount their horses to accompany me,” Lafayette wrote his wife Adrienne. “In short, my love, my reception here is greater than anything that I could describe to you.”[24]

From the harsh winter at Morristown, New Jersey, to the dwindling number of troops, to Benedict Arnold’s censure for misdeeds while governing Philadelphia, things seemed to be going from bad to worse. The position of the army had, in fact, become desperate. There was no money, so the men had not been paid in months. There was no food. Clothing and shoes were almost nonexistent, and many men went about barefoot and in rags. Ammunition was in even shorter supply than weapons.[25] 1780 had not started well, but Lafayette’s arrival indicated that perhaps things would soon improve.

On May 16, 1780, the Continental Congress “Resolved, That Congress consider the return of the Marquis LAFAYETTE to America, to resume his command in the army, as a fresh proof of the distinguished zeal and deserving attachment which have justly recommended him to the public confidence and applause; and that they receive with pleasure, a tender of further services of so gallant and meritorious an officer.”[26]

In June, Lafayette received a letter from Boston patriot Samuel Adams who wrote:

I had for several months past been flattering myself with the prospect of aid. It strongly impressed my mind from one circumstance which took place when you was at Philadelphia the last year. But far from certainty, I could only express to some confidential friends here, a distant hope, though as I conceived, not without some good effect: at least it seemed to enliven our spirits and animate us for so great a crisis. I was in the Council Chamber when I received your letter, and took the liberty to read some parts of it to the members present. I will communicate other parts of it to some leading members of the House of Representatives as prudence may dictate, particularly what you mention of the officers’ want of clothing.

I thank you my dear sir for the friendly remembrance you had of the hint I gave you when you was here. Be pleased to pay my most respectful compliments to the Commander in Chief, his family, &c. and be assured of the warm affection of your obliged friend and very humble servant, Samuel Adams[27]

On April 30, La Touche reported by letter to French Navy Minister de Sartine that there had been some minor damage to l’Hermione but also proudly reported that the copper sheathing of the frigate was in perfect condition. L’Hermione put to sea again on June 2, 1780.

Although l’Hermione is most significant to American history for bringing Lafayette across the Atlantic with the crucial news that French reinforcements of troops, frigates, supplies and money were coming to our assistance, she was involved in the American Revolution until after Yorktown.[28] On June 7, 1780, soon after depositing Lafayette in Boston, l’Hermione battled the 32-gun British frigate HMS Iris just south of Long Island.[29] The two ships exchanged a fierce cannonade for an hour and a half, during which Latouche was hit in the arm by a musket ball and l’Hermione’s rigging was damaged. A year later, l’Hermione was one of three supporting frigates in the fleet of Admiral Destouches in a clash between the British fleet and seven French ships of the line.[30] On May 4, 1781, l’Hermione was in Philadelphia where the Continental Congress honored her service in the previous year’s actions up and down the coast. Shortly thereafter, she was engaged in the naval battle of Louisbourg on July 21. On September 28, 1781, as the allied American and French armies began establishing their siege lines around Yorktown, and ships of the French fleet began blocking the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, l’Hermione arrived with powder and supplies. At the end of the battle, along with the frigate Diligente, and forty-four gun ship Romulus, l’Hermione wintered in near Yorktown, sailing home to France in February, 1782.[31]

A New l’Hermione

The story of Lafayette and l’Hermione has captured the attention of French and American citizens. A recreation of l’Hermione was conceived by members of the Centre International de la Mer in 1992, at almost the same time Americans began to seriously study French aid and historic locations along the Yorktown campaign route. Construction of l’Hermione-Lafayette began in 2007, and the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route (W3R) was approved by Congress. Now these international olive branches will meet, with a beautifully recreated French tall ship, Hermione-Lafayette, due to set sail in the spring of 2015, from the mouth of the River Charente in Port-des Barques where Lafayette boarded in March 10, 1780.

The tall ship’s voyage will be a 3,819 mile transatlantic crossing using eighteenth century technology. L’Hermione–Lafayette’s route will not be in historical sequence as hurricane season will be taken into account. L’Hermione–Lafayette will land at Yorktown, Virginia, where the original had engaged in the blockade that led to the British defeat and will spend the months of June and July 2015, stopping at twelve historic ports along the Yorktown campaign route. Related festivities, harkening back to Lafayette’s 1780 voyage to America, will bring both the story and the W3R National Historic Trail alive. UPDATE: L’Hermione is now back in it’s home port in France. Readers can track her current adventures at http://www.facebook.com/hermione.voyage.

For more information, please see:

and

http://www.nps.gov/waro/index.htm

[1] At thirteen, Lafayette became a sous-lieutenant in the King’s Musketeers. By seventeen he was a Captain in the Noailles Dragoons and later Captain in that corps.

[2] Quoted in James Gaines, Liberty and Glory: Washington, Lafayette and their Revolutions (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2007), 37.

[3] Letter to Adrienne Lafayette from aboard la Victoire, June 1777. Christine Valadon, translator, Cleveland State University Special Collections. Reel 23, Folder 202.

[4] Andreas Latzko, Lafayette: A Life (New York Literary Guild, 1936), 52.

[5] Laura Auricchio, The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), 78.

[6] Rupert Sargent Holland, Lafayette for Young Americans (Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1923; reprinted Ulan Press, 2012).

[7] Stanley J. Idzerda, ed., Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979), 2:230. Idzerda notes: “A nineteenth century note in the hand of Lafayette’s secretary has a marginal note: ‘Upon Lafayette’s first return it was thought that, in order to maintain the king’s dignity, which Lafayette had greatly offended by his disobedience, he must be exiled for several days and forbidden to see anyone but his family.’”

[8] Lafayette to Louis XVI. Paris, February 19, 1779, in Idzerda, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 232.

[9] Ibid., 355.

[10] Glenda Cash, trans., Le journal de bord de l’Hermione (Journal of the Hermione),

http://www.poplarforest.org/Democracy-Lafayette/logepisodes.htm.

[11] Idzerda, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 368.

[12] Stephen Bonsall, When the French Were Here (Garden City & New York: Doubleday, Doran and Company, 1945), 15.

[13] L’Hermione was commissioned in May 1779 under the command of Louis-René Levassor Latouche-Tréville, later to become the Comte de Latouche. A Rochefort-born aristocrat, he later became a noted admiral during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, 1801. Cash, trans., Le journal de bord de l’Hermione.

[14] Auricchio, The Marquis, 86.

[15] Cash, trans., Le journal de bord de l’Hermione.

[16] Lafayette, Memoirs, Correspondence and Manuscripts, 251.

[17] Lieutenant de vaisseaux was Louis-René Levassor, Comte de Latouche-Tréville

[18] Cash, trans., Le journal de bord de l’Hermione.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Lafayette (at Boston Harbor) to Washington, April 27, 1780, Lafayette Papers, 2:364-68.

[21] Cash, trans., Le journal de bord de l’Hermione.

[22] Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert de Motier Lafayette. Memoirs, Correspondence and Manuscripts of General Lafayette. Vol 1. (New York and London: Published by His Family, 1837; reprinted Forgotten Books: Classic Reprint Series, 2012), 251.

[23] Abigail Adams to John Adams, 1 May 1780. Massachusetts Historical Society,

http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=L17800501aa&bc=%2Fdigitaladams%2Farchive%2Fbrowse%2Fletters_1779_1789.php , accessed March 14, 2015.

[24] Auricchio, The Marquis, 86.

[25] Olivier Bernier, Lafayette: Hero of Two Worlds (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1983), 93.

[26] Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, nd), 17:432.

[27] Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Memoires of Lafayette (Boston: Knapp, 1824), 47, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html accessed April 2, 2015.

[28] Roger Marsh and Fiona Clark Echlin, “L’Hermione – building the Frigate of Liberty,” Ships in Scale, March/April 2014, http://www.galleryhistoricalfigures.com/LafayetteHermione.pdf

[29] Naval War College Blog. Newport, Rhode Island, http://navalwarcollegemuseum.blogspot.com/2013_04_01_archive.html#uds–search–results

[30] Albert Durfée McJoynt, “French Naval Leaders and the French Navy in the American War for Independence,” http://www.xenophongroup.com/mcjoynt/marine.htm , accessed March 28, 2015.

[31] Jacques de Trentinian, “De Grasse’s Naval Army (March 1781 – April 1782),” http://xenophongroup.com/mcjoynt/degrasse_fleet2.htm , accessed March 28, 2015.

See also: http://www.nps.gov/waro/learn/news/upload/February-2015-Highlights-Final.pdf, accessed March 28, 2015.

8 Comments

It always amazes me that this teenager attained the rank of general, having the wherewithal to assist Gen. Washington. Also, would anyone have information about Lafayette’s visit to Gen. William Floyd’s plantation, after the war, in the Town of Brookhaven, Long Island, NY?

Thanks, Zak!

I will be seeing some people who might know the answer to your question in June and will see what I can find out.

Great article, Kim. Thank you. Lafayette has always fascinated me and filling in the gaps in his story before his return to America was nice to read.

Very timely, too, since I saw the news item on the sailing of l’Hermione-Lafayette, arriving in America for festivities this summer, as you’d said. Thanks again.

Thanks, John. I am glad the word about this special tall ship is getting out. She is supposed to be one of the most beautiful and carefully constructed of all the tall ships to date. I am really looking forward to seeing her in Yorktown!

Just got around to reading the Lafayette article, now that l’Hermione is “once again” sailing for America, apparently this weekend. Very well done, a thoroughly researched piece on both the man and his important mission. Now if I can figure out how to catch up with that tall ship when it is stopping at ports on the East coast…

Thanks, Jeff!

You made my day!!! Here is the link to l’Hermione’s website. I hope you do get to see it! http://hermione2015.com/history.html

Kim

Thank you for this great story. Because of it, my family saw L’Hermione enter Boston Harbor on Saturday, July 11, 2015. As she left The Narrows and turned into President Roads channel, the fire ship waiting to greet her turned on its water cannons and escorted her in. She passed Fort Independence/Castle Island (where we waited) at around 8 am. As she did, she fired her guns thirteen times, just as the first L’Hermione did 235 years ago! Musicians on deck performed period music which carried across the water. An enormous Tricolor flew from her stern, and just above it flew a smaller Stars and Strips with the thirteen stars in a circle. It was a clear, bright morning. Wow! She is trés jolie, beautifully painted in primary colors! Unfortunately, she was not under sail, but was powered by a modern reserve engine. Sadder still, the crowd to greet her was not very big. However, what we lacked in size we made up in enthusiasm. We cheered wildly as she passed.

Sunday, July 12, we went to Rowe’s Wharf where she was docked and were fortunate enough to get a tour. The word “pretty” keeps coming to mind, though it seems an inappropriate descriptor for a man-o-war. I’m assuming the colors are historically accurate. She exudes a very different mood than the USS Constitution, for example. The crew is very sweet, very young, very dedicated, just like Lafayette.

Thank you, Rose! I am so glad you got to see l’Hermione! It is indeed a beautiful ship and I was thrilled to be onboard Delaware’s tall ship, the Kalmar Nyckel, as l’Hermione sailed by with both crews waving and yelling greetings! Truly a highlight of my life! I expect we will remember our experiences with this ship’s voyge until we are old and gray!!