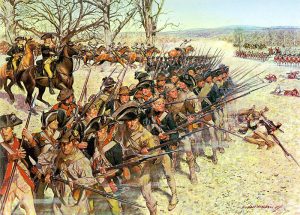

For contemporary Americans the difference between militia and regular, or “Continental,” soldiers is hard to grasp. Both fought in the war. Both suffered casualties. Both have supporters who claim they won the war. For decades after the Revolution, politicians spouted clouds of hot air on the subject, mostly aimed at denigrating the regular army in favor of the militia.

For contemporary Americans the difference between militia and regular, or “Continental,” soldiers is hard to grasp. Both fought in the war. Both suffered casualties. Both have supporters who claim they won the war. For decades after the Revolution, politicians spouted clouds of hot air on the subject, mostly aimed at denigrating the regular army in favor of the militia.

The militia long predated the American Revolution. As early as 1691 the Massachusetts charter empowered the royal governor to organize regiments of militia in every county. All able-bodied men between sixteen and sixty were required to serve. Each had to keep a musket, bullets and powder ready to repel an attack by the French or Indians. The militia was a kind of standing home army that met on training days to stay acquainted with handling guns and performing military maneuvers.

The minutemen were an elite group of militiamen who met and trained hard in the sixteen months between the Boston Tea Party and the battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. Many people, including members of the Continental Congress, have confused them with ordinary militiamen. The latter never approached the minutemen’s state of battle readiness. As a result the militia performed disastrously in the opening years of the Revolution.

In late 1776 George Washington, discouraged by the way militiamen tended to run away at the sight of a British soldier, wrathfully informed the Congress: “If I were called upon to declare…whether the militia had been most serviceable or hurtful upon the whole, I should subscribe to the latter.”

Emergency soldiers, summoned from home on short notice, the militia lacked confidence on the battlefield. But Washington eventually concluded that if they had a regular army to support them and “look the enemy in the face,” some of these amateurs were willing to fight and could inflict significant damage on the enemy.

Washington and some of his generals, notably Daniel Morgan and Nathanael Greene, learned to use the militia as auxiliary troops around a core of regulars with triumphant effect at battles such as Cowpens. At Saratoga the militia poured in after the Continentals had proved they could fight the British army to a standstill. Their raw numbers convinced General John Burgoyne that he was hopelessly surrounded. When the British invaded New Jersey in 1780, the militia, knowing the Continental army was in nearby Morristown, fought vigorously.

When the war shifted to the South and the southern Continental army was virtually destroyed by successive defeats at Savannah, Charleston and Camden, the militia under the leadership of experienced soldiers such as Thomas Sumter, carried the brunt of resistance for a while. But their lack of discipline and fondness for plunder alienated as many people as their battlefield valor encouraged. It required the revival of the southern army under General Nathanael Greene to make a decisive impact on the war.

At Bennington and Kings Mountain, the militia, again led by experienced officers, scored victories without the help of Continentals. When Washington marched to Yorktown, he left New Jersey completely in the hands of the militia. The conclusion seems inescapable: the militia could not have won the war alone but the war probably could not have been won without them.

After the battle of Springfield, two voices summed up the appeal of both types of soldiers. One of Washington’s officers, who remembered the starvation and neglect the regulars had endured during the brutal winter of 1780 in Morristown, wrote:”l cherish those dear ragged Continentals, whose patience will be the admiration of future ages, and I glory in bleeding with them .”

Yet even a sternly impartial historian must confess the appeal of the militia’s simpler, more spontaneous solidarity. In a mustering-out message to his regiment after Springfield, a New Jersey colonel took “the greatest pleasure” in the way the men under his command had lived “in the greatest harmony.” He hoped they would continue in “the same peace and unity…and convince the enemy’s of the United States that we mean to live and dye like brothers and go hand in hand in supporting our country against its aprosors….” [oppressors]

24 Comments

What a great subject. Thanks for just bringing it up. Among the things to remember about the militia is that each unit is unique. Not just in training but also in weaponry. For instance, very few southern militia regiments had bayonets or proper muskets. Providing arms for the militia remained a problem to the very end of the war. Many of the southern and backcountry regiments carried rifles instead of muskets and were incapable of holding a bayonet anyway. So, just exactly how are men without 18 inches of cold steel of their own to stand to a British bayonet advance?

Well, we talk to old Dan Morgan and find out that his secret at Saratoga was to mix his own regiment of riflemen with Dearborn’s light infantry. Once the British advance got close enough they could beat a hasty retreat while the light infantry came on with their own bayonets to hold the ground. It seems that, even before Von Steuben there were a few Continentals armed and ready to meet such an advance. They just needed the right equipment and some experience with the subject.

Sad that Gates and Williams didn’t learn the lessons of Saratoga and apply them at Camden. Instead, inexperienced and underequipped militia from North Carolina (not backcountrymen) were placed to face the right wing. Hopeless.

so bring on Morgan, Howard, and Pickens. Once again, the militia are without bayonets to stand the advance but are quite capable of getting in some licks at a good distance. Then, beat a hasty retreat and let the Continentals face a depleted and tiring British bayonet charge. Excellent!

Anyway, not just the militia men but what equipment do they have? what strength do they bring to the table? use it.

Just to mention one more instance in the southern campaign of militia saving the day. Prior to Guilford Courthouse, Greene did not have the manpower to stand up to Cornwallis and ran away across the Dan to Virginia. Jefferson called out the militia to help. Specifically, one group was the Lunenburg County militia from the Lynchburg area. They were a a regiment consisting largely of men with previous service in the Continental Army. The raising of the VA miltia gave Greene the strength to stand at Guilford and bloody some of Cornwallis’ best soldiers.

I could continue about the southern regiments. Overmountain Men were quite a different animal from the embarrassing militia from Charleston and the low country. Those without knowledge of how southern militia fought haven’t heard about battles like Blackstocks Plantation where Thomas Sumter’s men stood fast and taught Tarleton’s dragoons the meaning of fear. Sorry to get wordy. Love the subject. 🙂

The American militia continues to fascinate me as a topic for further exploration. Is there a defining work, out-of-print or otherwise, that covers the subject matter, or is one relegated to reading the various more localized studies? Thanks for an appetizing article.

The question of whether the patriot or loyalist militia were more effective has not been adequately explored. In both the northern and aouthern theaters, opposing militias were well matched. Certainly continental officers either lauded or blamed militia units more than British officers who neglected to give much credit to loyalist units..

One of my favorite books on the subject of militia and minute men is “The Minute Men: The First Fight: Myths and Realities of the American Revolution” by Gen. John Galvin.

Here are my choices for bests books on Whig militias:

The Minutemen and Their World (American Century) by Robert A. Gross

The Minute Men: The First Fight: Myths and Realities of the American Revolution (History of War) by John R. Galvin

The Day It Rained Militia: Huck’s Defeat and the Revolution in the South Carolina Backcountry, May-July 1780 (SC) by Michael Scroggins

A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens by Lawrence E. Babits

The Battles of Kings Mountain and Cowpens: The American Revolution in the Southern Backcountry (Critical Moments… by Melissa A. Walker

Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer

Forgotten Victory: The Battle for New Jersey –1780 by Thomas J Fleming

Thanks for posting this article–it prompted some random thoughts in my enfeebled mind. (1)The Americans, in general, and militias, in particular, tended to fight better from behind entrenchments–think Bunker Hill. (2)The Americans probably lost the battle of Hubbardton because the militia refused to move to the action. (3)The majority of discussions of militia center on the southern campaigns. (4)There is very, very little discussion of loyalist militias. Those interested should visit Todd Braisted’s “On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies” at http://www.royalprovincial.com/index.htm.

The subject of the militia is indeed an interesting one and one that has not received the research attention it deserves. It is also an extremely complex subject because while there was one Continental Army there were thirteen militia structures and within each of those there were variations in local conditions and situations. It is also complex because the militia was asked to do a great deal more than fight in pitched battles, with or without the Continentals. To simply judge the militia as soldiers in formal battle misses a great deal of the picture. To answer Steven’s question on further reading, it is definitely necessary to look at local situations rather than a generalized account of the militia.

In doing the research for my book on the First Hunterdon County, NJ militia regiment (A People Harassed and Exhausted) I found that New Jersey’s militia situation was quite different from most other states because of the nature of the war in New Jersey – “The Crossroads of the Revolution.” When evaluating contributions to a military effort there is more to consider than simply fighting in battles. New Jersey’s militiamen were also asked to prevent trade and information going to the British on Staten Island throughout the war from July 1776 on. They were also on guard to prevent British foraging and other incursions from New York. During the British occupation of Philadelphia they also had to prevent the same things on the western side of the state.

New Jersey’s militia laws and situation led to the expectation that militiamen would be called out for active duty every other month, so a good portion was on duty all the time. They were also fighting a civil war. At the same time they were expected to keep the economy of the state going, especially growing crops and raising animals that could be used to feed the Continental army during its several winters in the State. They were also expected to help transport food to the army and, until a law was passed to help them, some men paid fines for not turning out for their alternate month duty because they were driving supply wagons for a couple of weeks for the Continentals.

I my article in this journal several months ago I tried to highlight one way that militiamen contributed to the Battle of Trenton by guiding Washington’s army to the town. I found it extremely interesting, and telling, that historians have looked at the guides as simply local farmers who volunteered to guide Washington, while in fact they were militiamen who were out on active duty and were recruited from their companies. Their contribution isn’t as juicy as standing up to the British in a bayonet charge, but what might have happened if Washington had lost his way that important night when he was already behind schedule?

I chose the title for my book from a quote by George Washington describing why it might be that New Jersey was having trouble getting men to turn out for militia duty. Another phrase I could have used was one from New Jersey Governor Livingston in which he described the militia laws of the State as placing an inordinate burden on the willing – that is, those willing to put up with the frequent call outs which a lot of men avoided in various ways.

Perhaps the most important thing I learned in my research is that one should not extrapolate generalities about the militia by looking at one area or one time during the war. Another lesson learned was that it is unwise to look at how things were supposed to be, by law, rather than investigating how they actually played out.

I would respectfully ask that we not continue to try to compare the effectiveness of the Continentals and militia – after all there were times when the Continentals performed well and times they didn’t – just like the militia. Instead, let us try to understand the contributions made by the men in each situation, why they excelled or had difficulty, how each suffered at times, etc. Just as with the Continentals there are some great stories to ferret out about how men dealt with difficult situations and sometimes did amazing things (often without credit) and sometimes failed. Let’s look at and understand them as humans and not stereotypes.

All great and valid points. They are indeed two different kinds of animals and need to be assessed individually on their own strengths and weaknesses.

When I was researching my first book, it took me deep into the town meeting minutes of Groton, Massachusetts for 1774-1777 and it was an eye opener with regard to the demands that recruiting and equipping local soldiers had on the inhabitants. The Provincial Congress was acting on its own by and large, separate from the Continental Congress in those early days and it facilitated a number of call ups to support Washington in late 1775 and early 1776.

As a result, Groton officials had to find and send local men on no less than four separate occasions over the course of the year: 1) Lexington Alarm; 2) to assist with security as other militia units left Boston (the Eight Months Men and Connecticut contingencies threatening mutiny) before the Army went into existence on January 1; 3) to the Siege of Boston; and, 4) then to Mt. Independence and Ft. Ticonderoga for security as the Northern Army retreated from Canada.

Each one of these events involved no input from the Continental Congress and they imposed great stresses on the town as they came up with pay, food, equipment, etc. for their support. As time went on and other demands were made for clothing and beef to feed the national army, they found they could not meet their quota of soldiers and were forced to hire people to go to other towns to find volunteers to stand in.

A state-wide classification system was set up (towns could volunteer to participate) wherein the town was sectioned off according to levels of income and then they were told how many men they had to come up with. If they did not, then their taxes were raised accordingly to the amount needed to hire someone to satisfy that assessment. Needless to say, levels of debt increased and, when compounded by monetary problems that lasted well beyond the war, it is easy to see why that thing called Shays’s Rebellion broke out.

In short, the demands imposed on the towns to field and sustain militia troops posed a very real and direct hardship on townspeople. While it was certainly also difficult for the army, their problems were not of the same ilk. Militiamen were tied so much closer to their hometowns that they felt a direct connection and responsibility for having made life difficult for family and friends.

So, it seems quite natural that there would not be any correlation in competencies when comparing regulars and militia. Yes, they each wore uniforms and fought when called on, but their underlying motivations were definitely not always the same.

So you are saying that militia served side by side with Continental Line soldiers during some of the battles. Correct? The reason I am asking is I believe my ancestor, Jacob Tanner, who was Continental Line died along with his brother, Christopher Tanner, who was militia at Yorktown. Christopher was in Culpeper Class #73 and Jacob was the chosen draftee from that same class for the Continental Line. Christopher is recognized on a plaque at Yorktown and Jacob is not. Jacob was alive when his father wrote a will in May of 1781; however, he died before March 10th of 1782 when his wife paid the required personal property taxes. I am just trying to pin down where and possibly when my Jacob may have been killed. His wife received a pension from the State of Virginia. This pension states Jacob died while serving in the War.

Question….is the Revolutionary War Continental Army and the Continental Line the same? I have an ancestor who was born in Johnston County, North Carolina, moved to Cumberland County, NC, with his parents when he was 10 years of age and lived in North Carolina with a militia voucher from the Wilmington District in 1783, who then migrated to Washington County, Georgia, shortly after the war, because he received 3 bounty land grants for his service in Washington County, a location that I researched to be only Georgia Continental Line recipients. I am being told that he cannot have served two states in the Revolutionary War. My question is a result of empty findings in the NARA microfilm military records of his service. These records state in their “Introduction” that the Continental Army records burned in 1800. Which leads me to believe that the remnants of service records are Continental Line service, possibly why I cannot find his service. Can anyone answer my question and provide a source for your answer?

Lisa;

The “Continental Army” was formed of regiments that were provided by the 13 colonies and a couple of regiments formed in Canada (like Hazen’s). Some of these were raised as independent regiments, some were State Militia or State Line regiments that were voluntarily nominated to Continental service; but the vast majority of State regiments were raised in response to quotas passed in acts or resolutions by the Continental Congress. Each State’s “quota” was named in a line item within the act; thus these regiments came to be known as the Continental “Line” regiments. As the war went on the Continental Army was re-formed a couple times. The first of these was in January 1776. At that time most of the enlistments had run out, and the Continental Army was reformed into a system recommended by George Washington and adopted by Congress as legislation. Later that year, 16 September 1776, created the “third establishment” of the army which included a quota system for 88 regiments; providing a “line” in the legislation enumerating each state’s “quota”. The majority of the original “volunteered” regiments were either superceded or incorporated into the line regiments assigned as quotas to the various states, and thus became “Continental Line” regiments. The term “line” eventually came to apply to regiments officially nominated by its state to serve on “Continental establishment” (being accepted by the Congress as part of the continental army and drawing continental pay).

At the time of the Revolutionary War Georgia was a relatively new colony. Many of the settlers were fresh immigrants; with fresh ties to Britain. There were also a number of established planters along the coast whose livelihood depended on the British mercantile system. As a result, Georgia was a small state population-wise with a relatively high ratio of loyalism. Georgia didn’t even send delegates to early sessions of the Continental Congress because her protection against hostile Cherokees was dependent upon the British Army, who the state’s leaders did not want to alienate. Congress recognized that Georgia would have a hard time filling her congressional “quota” of troops, and only issued a quota for one regiment. The first Georgia “line” regiment was authorized by act of Congress 4 November 1775 (1st Georgia, Lachlan McIntosh commanding). The 16 September, 1776, act retained one Georgia line regiment (1st Georgia, Joseph Habersham commanding) (although Georgia also provided a small regiment of “Horse Rangers”).

In addition to Georgia’s one-regiment “quota”, there were other units which were raised outside the state at various times and for various reasons. In a “resolve” passed by Congress on 15 July 1776, Georgia was authorized to recruit in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina two infantry regiments and two artillery companies. These regiments and artillery also served with the Continental Army as “line” regiments. These troops were authorized to be enlisted for one year, which expired in 1777. Given that your ancestor hailed from North Carolina, its likely he was recruited into one of these units.

That would also fit your statement that your ancestor was discharged and then enlisted again into a different unit: his original unit may have been disbanded. Many men throughout the war served in units from other states. It was entirely possible to be discharged from a unit from one state and then re-enlist into a unit from another state. During the war the enlistments of all regiments declined over time as men were discharged, became sick, were wounded or killed. As the regiments became ever smaller, there came a point where they had too few men to fight effectively. At that point they were combined with other small regiments to form “battalions” as a fighting unit. Thus, men from one area of the country might end up serving with men from other areas. Bonds of friendship and trust probably formed, and men became comfortable with officers from other states or regions. So, when it came time to re-enlist, it made sense to fall in with the men and officers you knew and trusted.

You might start by perusing “Georgia’s Roster of the Revolution” ( https://archive.org/details/georgiasrosterof00georuoft ). It’s free and you’ll see the entire content at that link. It contains many names and pension applications compiled from sources other than NARA (which is limited due to the archive fire of 1800 as well as British arson in 1814). After that, try Google… and don’t be afraid to use genealogical sites like “Ancestry.com” to see if anyone else has discovered data on your revolutionary.

Good luck!

P.S. to all the Georgia experts: I know there were other Georgia units with great service; Lisa specifically asked about Continentals so I limited my response to these units

Lisa,

I’ll add another potential source – town meeting records. I have spent a lot of time reading the Groton, Massachusetts records for this period and was surprised to find discussions about the difficulty the town had in meeting its imposed quota (which came down from the provincial government). The town was broken down into various classes and each one told to come up with a particular number of men or to provide an equivalent in feed, clothing, meat, etc. instead for the Continental Army. They also had the option of hiring people from outside of the town and even sent agents around the countryside to find substitutes, and which included the names of various individuals.

It is also possible that there are muster rolls for the town either locally or in your state archives that can provide further details of men sent from towns into continental service. Good luck.

Lisa,

Good question. The short answer is “It depends.”

It depends on how the system was set up in North Carolina and in Georgia. I study Northern Army units, and mostly New York regiments early in the war, so I cannot help you there. You would best be helped by someone who as an expert on those regiments.

I can explain the New York system included Continental regiments, State Troop regiments (they called levies) that were militia on long term Continental service, and various ad hoc militia regiments, they also called “levies,” that were drawn for short term Continental Service. This shorter service could be for months, weeks, or even just a few days. Often these units included both mounted and dismounted troops that worked together as a sort of legion. In addition, there was the regular Militia that stayed close to home. All men 16-60 were required to serve. These units were often used as a pool of troops to be drawn on for the various Levy units being formed. The uniformed Independent Companies that were found mostly in New York City and Albany were a sort of early-form of 19th century Marching and Chowder societies. Mostly they were for show, but when NYC was attacked in 1776, they took an active role and were formed into their own battalions.

In addition to the state affiliated continental regiments, there were also the numbered regiments with no state/colony designation. There were also unnumbered regiments, with only the name of the colonel.

I am not at all trying to discourage you. By any stretch of the imagination it is a daunting to figure it all out…and this is only the basics for one colony. Plus, to add to the confusion, family historians can get unit names, battalions, regiments, brigades, and other such designation so buggered up that future generations of the family are looking for a non-existent Continental Regiment. They could be looking for, say, a member of the 1st company of the 5th Anywhere regiment, but he was actually in the 1st regiment of the 5th Militia Brigade….

Your best bet is get fundamental understanding of the Continental Regiments in the area of your concern. The out of print Encyclopedia of Continental Army Units, Battalions, Regiments, and Independent Corps, by Fred Anderson Berg (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1972), is a good place to start to understand the basics of the Continental Army…….. For militia units in the Carolinas and Georgia, I am out of my league there.

To you other question, no one could legally serve in regiments from two different colonies/states, or even the same colony/state, at the same time. One could serve in one unit and when their enlistment was up, join another unit across the border. I have plenty of evidence of this happening between Northern New York soldiers and those in Western New England. I even know of an entire company that swapped from New York to Connecticut. One officer, I am going to write a brief article for the JAR, migrated from a New York unit to Connecticut and then another, and finally the 2nd Dragoons, a Connecticut based unit. Though a New Yorker all his life he joined the Connecticut Society of the Cincinnati after the war and not the one in New York.

Have fun.

Phil

Thank you- very helpful to me as I’ve been trying to figure out what was meant by “New Levies” after my ancestor’s name in a “Rangers on the Frontier” index.

Phil – were the levies full-time soldiers? Thanks. Vic

As far as New York goes, the levies, in all forms, were full time. There length of service would vary depending on the mission they were formed to accomplish. They also generally wore their own clothes, so looked like militia, even though they were part of the Continental Army.

Jim, Gary and Phil: You guys are AWESOME!!!! and definitely answered my question, explaining my North Carolina ancestor’s multiple service. Which brings me to ask another question. In North Carolina (and I believe in most states during the Revolutionary War) the soldiers received their “pay” at the end of the war which occurred post 1783 relatively speaking. My question is… at the beginning of the war in 1775, my ancestor was 21 years old and lived in Cumberland County which was in the Wilmington Military District, but by the end of the war in 1783, he acquired 400 acres and was found in Montgomery County which was designated in the Salisbury District. I am positive he first fought in the NC Militia and then fought as a soldier of the Georgia Continental Line so if his original enlistment in the North Carolina Militia occurred while he was residing in Cumberland County, wouldn’t he be paid by the original military district he was in at the time of his enlistment? (I am being told differently…that he would be paid from the Salisbury District or his current county of residence at the time). Accounting logic tells me he was an expense of the Wilmington District and they would have his pay voucher records…not Salisbury.

You all have been a wealth of information and I can’t thank you enough.

Lisa;

Your next question is clouded by a myriad of confusing pay, bounty, and pension schemes which pertained to Revolutionary soldiers. I’ll try to put the various facets into some context.

Pay: Soldiers, whether militia men, State Line enlistees or continentals, were supposed to be paid each month during their service. Frequently they were not paid on time because of fiscal shortages or the shortage of actual currency. Those in Militia service were paid by the town or county government (sometimes this would be the local “Committee of Safety”) where the militia unit was formed. Men usually, but not always, entered militia service in the town/county where they lived. Men who enlisted in “State Line” regiments – units which formed a standing army for state service – were paid by the state. Men on “Continental establishment” were paid by Congress; who authorized pay to be sent to the army paymasters, who then dispersed it to the units. This included men who were sent as “levies”: militia or State regiments sent to the Continental Army for short term, fixed duration periods (usually a month, but in a couple extreme cases in Virginia levies served for a year unless replaced by a substitute from their home militia). There are any number of stories regarding pay issues with the Continental Army, but in cases where men reached the end of their enlistment and were owed back pay, they were either paid at the time of discharge or given certificates for the amount of their pay. The certificates, in theory, could be cashed by a congressional paymaster or by a state or local governmental official who would then be reimbursed from Congressional coffers (in practice the states simply deducted the amount of the certificates from the payments they were sending to Congress). There were also speculators who would offer men pennies on the dollar for their certificates – men would accept these paltry sums because they were often discharged great distances from home and needed money for their trip. At the end of the war the Congress owed about $10.8M to serving Continental soldiers and officers. That money was paid in the form of “certificates” by Colonel John Pierce (whose four volume account book is known as “Pierce’s Register”, available on line) who issued 93,298 certificates to individual soldiers to settle that debt – the vast majority to men who were still serving at the end of the war (many men received multiple certificates). So, the bottom line to the answer to this part of the question would be that your ancestor would have been paid by his continental paymaster for Continental service, and by the town which sponsored the militia unit for any militia service, or by the state for State service. If you are certain that his militia unit was raised in Cumberland County, then he should have been paid by them and should be found in their muster rolls. Finding your ancestor on a muster roll and determining what type of unit he served in and where it was formed, are the first step to finding his pay records (and will probably simultaneously return his pay records). For a start on NC Revolutionary War records, try Googling North Carolina Daughters of the American Revolution, “Roster of Soldiers from North Carolina in the American Revolution, with an Appendix Containing a Collection of Miscellaneous Records” (Seeman Press, Durham NC, 1932). I’m a big fan of “Fold3.com”. Fold3 contains about 430,00 individual names of Rev War participants and includes records not only provided by NARA, but also those documented by organizations like SAR, DAR and state historians.

Bounties: Debt that was not paid during the period of enlistment primarily included bounties. Cash enlistment bounties were paid at the time of enlistment. Land bounties were not – they accrued over the enlistees duration of service or were only due if the soldier fulfilled the terms of the bounty (some duration of time in service or service “to the end of the war”). There were continental land bounty programs and state land bounty programs; and most of the state land bounty programs were not conceived until after the war had ended. North Carolina had an incremental land bounty system drafted in late 1776 which began paying men land upon completion of 24 months (not necessarily continuous) and incrementally increased the land for increased service, peaking at 84 months of service. These land debts were paid after the war. North Carolina’s land bounty debt was satisfied with land that the state had reserved for this purpose when ceding her western territory claims to the Continental Congress in 1781. These ceded lands eventually made up the states of Tennessee and parts of Kentucky. Since you stated that your ancestor’s land was in Georgia, he probably did not accrue North Carolina land bounties. Georgia had a land bounty system that was created after the war ended. Is was noticeably broad and not only provided land for military service (of any type), it even provided land in compensation for confiscations made during the war – even to loyalists. One of the best-known recipients of Georgia’s land bounty program was Gen. Nathanael Greene, who removed himself from Rhode Island to Georgia to live on his bounty land (he’d been bankrupted as a result of his war service and Georgia and the Carolina’s helped him out). As previously mentioned, Georgia was a new, little populated state but land-rich. Land bounties were a way to keep current residents and attract more; especially to the western regions being contested with the native populace. The book I linked in the previous post includes a wealth of Georgia land bounty recipients. You may well find reference to your ancestor among the Georgia Revolutionary War land bounty records (Google that phrase).

The final payment that soldiers became eligible for was a pension; either congressional or state. Pension programs were not established until decades after the war ended. The most prominent, and also the broadest, was the congressional program enacted in 1832 – almost 50 years after the war. Pension programs provided an annual stipend to Revolutionary War veterans and surviving spouses were eligible to claim on behalf of their veteran husbands. The process involved the veteran or claiming dependent to appear before a judge and make a sworn statement regarding their service; and to offer proofs (enlistment or discharge papers, etc.) and corroborating testimony from other veterans. Many of the pension claims contain fantastic accounts of their service! Searching by name for your ancestor in Revolutionary war pension records may turn up a wealth of information. Since you think that he served with the Georgia Continental Line, he would have been eligible for a congressional pension. Some dedicated souls have worked hard over recent years to digitize pension records. Googling “Revolutionary War pension records [your ancestor’s name]” will hopefully garner some hits.

Again, I hope this provides some context for your search!

Jim: Thank you so much for this information. I hope my questions also help others with their research. I know it will definitely help me. I’m eager to reference your leads.

I didn’t read all the comments so this may have been covered. My understanding about Militia is that they may or may not have had proper military arms and accoutrements. I think it is a myth that every Militia unit wore civilian clothing and used hunting rifles. There was Militia used in the F&I War and they were not all out of uniform or without Bayonets. Why would the Militias in the Revolution be under equipped with military weapons. Minutemen are something else. Life on the frontier from Jamestown and Plymouth onward required a Militia trained armed and equipped. My understanding of Militia is that they are regulated troops but not a standing army called out by the Governor in times of emergency. Armed and trained with military weapons. I just don’t by the image of all militias being without bayonets. Especially after the F&I War not so long before the Revolution.

Very polarizing topic to many. The most truthful comment is that both Continental regulars and each colony militia were essential in winning the Revolutionary War. To generalize across the colonies on militia on deserting, running, weapons, training, … and soforth is sophomoric and naïve. A study in Clausewitz, knowing terrain, intelligence, supply lines, friend and foe; especially in the Southern campaign were vital. In the South, the militia were critical. Many southern militia had rifles, superior in killing British officers at a distance (ask Tarleton) however lousy in bayonet frontal assaults. Morgan knew this, however Generals Robert Howe, Benjamin Lincoln, Horatio Gates, and even Nathanael Greene continually did not learn. Few hated the British more than Morgan after he learned first hand with his cousin Daniel Boone and a man named Braddock . The war in the north (that Washington knew) and the southern war (without an accomplished Continental leader) were vastly different in geography, tactics needed and employed, and use of the available militia. Oft Mis-used, questionable leadership, travels away from their family that needed defending, and so forth may provide a better understand of the militia — as opposed to claiming they plundered and fled. Also Sumter, Pickens, and Marion employed differently in a complex ‘arrangement’ with Greene. We certainly needed all these men when the Continental regulars and leaders ran away after the fall of Charles Town. Amazing how easy generalist statements seem to characterize beliefs that an examination proves largely false. Time and space does not permit, but I love good debate on merits and OOB (order of battle).

In a comment concerning militia’s importance in the Revolutionary War, J.B Eleazer wrote “A study in Clausewitz, knowing terrain, intelligence, supply lines, friend and foe; especially in the Southern campaign were vital. ”

Not knowing just what he or she meant by “a study in Clausewitz,” I will note only that Clausewitz did not write “Vom Kriege” until some time after 1815, and that it was published posthumously in or around the 1830’s — and then, I think, only in German.

Appreciate the reply. Well aware of the timeline. My reference of Clausewitz is a reference to the very fact that knowing the terrain, intelligence and supply lines… are critical in a partisan war. Just because Clausewitz acknowledge this in his long papers on military strategy AFTER the American Revolutionary War does not make it not a fact in importance. Morgan, Sumter, Marion, Thomson, and many others learned this lesson hard during the Cherokee Wars prior to the American Revolution. This was my point. As an example. General Gates refused help from cavalry colonels William Washington and Walton White as Gates marched off towards Camden in July 1780. He also dispatched Marion and Sumter in different directions (however for good reasons), but it left Gates without experience in the area, without ability to ensure supplies, and clearly into a Loyalist territory. For this reason, Gates had very little supplies and support with disastrous results, many of the soldiers were sick before the battle. As far as South Carolina, the rivers and swamps provided unique barriers as well as defense. Many stories underscore this in ambushes, switched loyalties, and delayed/lost detachments. Obviously this was used to the maximum by General Marion.