Until 1765, there were no medical schools in the American colonies. In the words of one historian, a man aspiring to the medical profession was

obliged to acquire his training as an apprentice to an older doctor. Beginning usually at fifteen years of age, he took care of the physician’s office and his horse, and made himself generally useful. Little by little he was taught how to prepare prescriptions, to assist at blood-letting and, as he progressed, was allowed to accompany his master on his daily rounds. He was encouraged to study his mentor’s books.1

A few Americans went abroad for their medical training, especially to the medical school of Edinburgh University.2 Returning home, they launched the independence of the teaching and practice of medicine in the American colonies.

William Shippen Jr. was a member of Philadelphia’s distinguished Shippen family. (Margaret “Peggy” Shippen, wife of America’s most infamous traitor general Benedict Arnold, was a relative.) John Morgan (born 1735) and William Shippen Jr. (born 1736), departed Philadelphia for Great Britain to study medicine. Morgan studied “under the most celebrated masters of every branch of medicine.”3 Both men attended the anatomy demonstrations of John and William Hunter in London. Describing Shippen as a “sober and discrete young man,” and holding Morgan “in great esteem,” Benjamin Franklin—Philadelphia’s leading citizen—recommended them for acceptance into the University of Edinburgh medical school; the premier medical school in the English-speaking world. While abroad, Morgan and Shippen, “two zealous and enthusiastic young men [developed] the plan of establishing a medical school” in Philadelphia. Franklin wished Morgan “a prosperous completion of your studies, and in due time, a happy return to your native country.”4 Morgan and Shippen “wanted to bring medical education to America, so others would not have to . . . travel half a world away to receive an education.”5

On his return to Philadelphia in 1761, Shippen offered a series of lectures on anatomy and midwifery, the first courses on these subjects given in America. “The lectures by Dr. William Shippen, Jr., were thus in full operation when, in 1765, Dr. Morgan arrived from Europe.”6 Days after his return, Morgan submitted a detailed plan to the trustees of the College of Philadelphia to establish a medical school, based partly on Edinburgh model; the same year, the British parliament passed the Sugar and Stamp Acts, that began the conflict between the mother country and its American colonies. John Morgan envisioned medical education in America as the combination of the existing apprenticeship system and a university education, with knowledge of human anatomy, physiology, pathology, chemistry and pharmacology. “Latin and Greek are very necessary to be known by a physician [as well as] an acquaintance with mathematics and natural philosophy.” The student should serve three years as an apprentice to “some reputable practitioner of physic [medicine]” as well gaining knowledge in the medical school and experience in the hospital. Morgan informed Benjamin Franklin of his plan. In his response, Franklin wrote: “It rejoices me to hear that you got well home, and that you are like to succeed in your scheme of establishing a medical school in Philadelphia.”7 Philadelphia, then with a population of under 25,000, was home to the first medical school in North America. Franklin anticipated that “in a few years, with good management, [the Philadelphia medical school] may acquire a reputation similar and equal to that in Edinburgh.”8

In September 1765, Dr. William Shippen Jr., was elected professor of anatomy and surgery and John Morgan professor of the theory and practice of physic. In 1767, Shippen informed Franklin that he had submitted to the Royal Society a wax rendering of his dissection of “two female children joined firmly together from the breast bone as low as the navel, having therefore but one body; in every other respect, as well internal as external, two complete children.” Shippen hoped “that this phenomenon will be enabled to throw some light on that unintelligible work of Nature.”9 The visionary John Morgan was so “determined to be at the head of medical affairs in Philadelphia [that he] ignored William Shippen in the plan for the medical school . . . Shippen had too much pride, too much ability, and too many friends to submit quietly to the repeated insults.” Morgan and Shippen began their intense rivalry to be recognized as the founder of medical education in colonial America.10 In 1767, Adam Kuhn graduated from the University of Edinburgh and on his returned to Philadelphia was appointed professor of materia medica [pharmacology]. In 1765, Benjamin Rush attended the lectures of Morgan and Shippen. In 1766 he began three years of study at the Edinburgh medical school. In 1769, twenty-four-year-old Rush returned to Philadelphia to be appointed professor of chemistry at the new medical school. Lectures were held at Surgeons’ Hall on Fifth Street. In June 1768, the Philadelphia medical school had its first commencement, with eight graduates.

New York

Samuel Bard was born 1742 in Philadelphia. At age four he moved with his family to New York. He was educated at King’s College (now Columbia University) and, at age twenty, began his studies at Edinburgh medical school. In Edinburgh, Bard learned of plans to open a medical school in Philadelphia. In a December 29, 1762 letter to his father in New York, Bard wrote:

I wish with all my heart that I might . . . assist in founding the first medical college in America . . . I am afraid that the Philadelphians, who will have a start of us by several years, will be a great obstacle . . . I will feel a little jealous of the Philadelphians and should be glad to see the College of New York at least upon an equality with theirs.11

Bard’s Edinburgh graduation thesis was on the actions of opium, with himself as the subject. He demonstrated that opium, long considered a stimulate, was a sedative.12 Coming home in 1767, Bard persuaded the board of governors of King’s College to open a medical school in New York. Like the one in Philadelphia, the New York school was modeled on the Edinburgh medical school. Irish-born Samuel Clossy was appointed professor of anatomy, Peter Middleton, physiology and pathology; John Jones, surgery, James Smith, chemistry and materia medica, John Tennent, midwifery, and Samuel Bard, at age twenty-eight, was appointed professor of the theory and practice of medicine.13 In 1769, Robert Tucker, Caleb Cooper and Samuel Kissam were its first graduates. Between 1770 and 1775, seventeen doctor of medicine degrees were conferred by King’s College medical school. Professor John Jones’ Plain, Concise, Practical, Remarks on the Treatment of Wounds, published in 1775, was the first American surgical textbook. That year, the newly built New York Hospital caught fire and was destroyed. The New York medical school shut down in 1776. John Clossy, a loyalist, fled New York and returned to Ireland.

The Revolutionary War

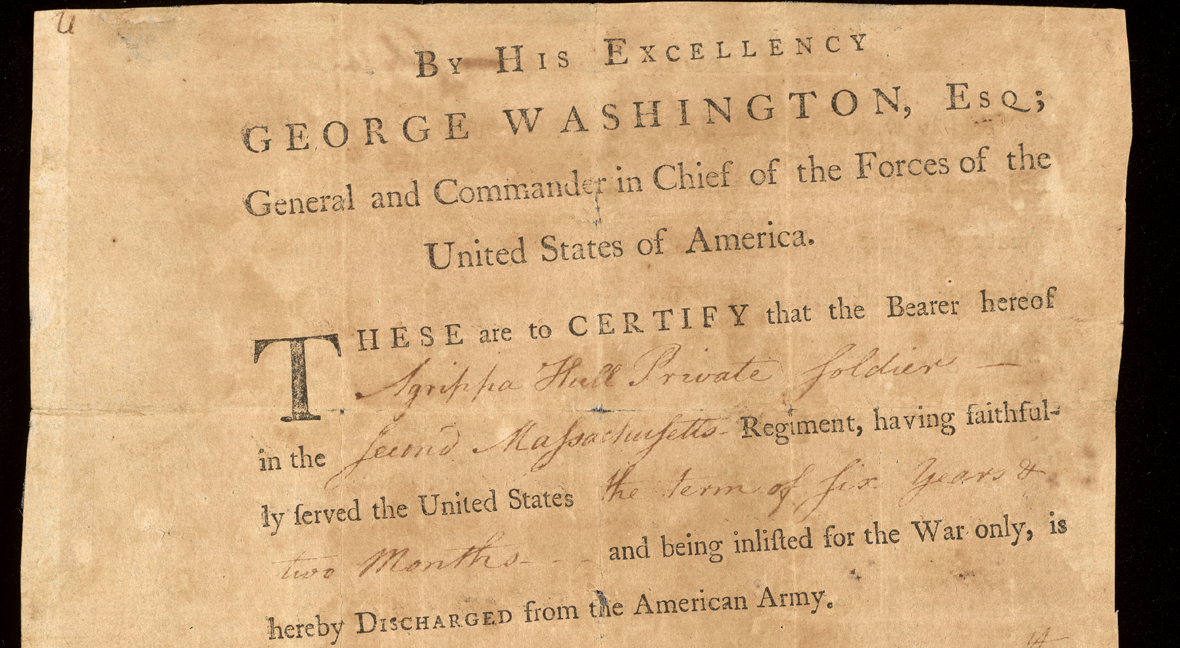

On June 19, 1775, the 2nd Continental Congress appointed George Washington commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. On July 27, Congress established the army medical department; the New England states formed the Northern District of the army medical department; New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania the Middle District, while the southern states comprised the Southern District. The 1,200 physicians who served in the American Army’s medical department during the Revolutionary War “were all civilian practitioners, many without any military experience.” Fewer than one in twenty of the 3,500 physicians in the American colonies at the start of the Revolutionary War held university degrees. The overwhelming number trained as apprentices or were self-taught with little scientific knowledge.

“The medical services of the Continental Army during most of the Revolutionary War were disorganized and inefficient,” wrote one historian. “Chronic shortages of foods, medicines, and clothing, a continuing quarrel for precedence, power, and supplies between the regimental and general hospitals, ill-trained surgeons and mates, the failure of general officers . . . were the basic ingredients of disarray and failure.”14

Appointed on July 27, 1775, Dr. Benjamin Church of Boston was its first director general and chief physician of the Continental Army medical department. A secret loyalist, Church passed information to the British army. A court of inquiry, headed by general George Washington, found Church guilty of treason. “The fall of Dr. Church, has given me many disagreeable reflections, as it places human nature itself in a point of bad light, but the virtue, the sincerity, the honor, of Boston and Massachusetts patriots in a worse light,” wrote John Adams to his wife Abigail.15 The three intensely patriotic Philadelphians John Morgan, William Shippen and Benjamin Rush occupied senior positions in the medical department of the Continental Army. Morgan was named director of hospitals, Shippen was chief physician and director of the army hospital in New Jersey and then director of all the hospitals west of the Hudson River. Rush represented Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress, served on its medical committee, signed the Declaration of Independence, and was physician-general of the Middle Medical Department of the Army. Loyalist Adam Kuhn fled Philadelphia for the Caribbean. With the departure of its leading professors, classes at the fledgling Philadelphia medical school were disrupted and came to a halt when the British army occupied the city in the fall of 1777.

Classes at the Philadelphia medical school resumed in 1780. Adam Kuhn returned from exile to take Morgan’s position as professor of the theory and practice of medicine. On May 11, 1780, Shippen was elected professor of anatomy and surgery. On January 4, 1781, Shippen informed general Washington that his

duties of the director of the hospitals are incompatible with those of the professor of anatomy & finding a great number of young gentlemen from different parts of America waiting here for my course of lectures—I have sent in my resignation, convinced I can be of much more use to the public, by fitting young gentlemen to act as surgeons in the army where good ones are much wanted, than by continuing director of hospitals, now in so good order & containing so few sick or wounded.29

In response, Washington complimented Shippen, saying: “I believe no hospitals could have been better administered: And this opinion I found upon the uniform reports of the superintending officers and upon my own observation.”30 After Shippen stepped down he was replaced as director general of the army medical department by Dr. John Cochran, with Dr. James Craik, second in command, and chief medical physician. The fighting ended before any newly-trained surgeons from the Philadelphia medical school could join the medical department of the army.

The fortunes of the Philadelphia medical during its first twenty years were “checkered and unequal.”31 Benjamin Rush and John Morgan notified the trustees “of their unwillingness to accept posts on the staff if Shippen were also elected.” The trustees “did not act as the two had anticipated.” When William Shippen was appointed professor of anatomy and surgery, Rush withdrew his rejection, joined the faculty, and gradually learned to get along with Shippen.

Morgan gave up his teaching position in the medical school he founded and “retired very much from active life, actuated by chagrin as to his treatment by Congress, in removing him from the post of director general, upon charges from which he was ultimately exonerated.”32 In 1784, John Morgan read a paper entitled On the Construction of Air Balloons and the several uses to which they may be applied. He proposed a plan “to construct and raise an air balloon of such magnitude as to be capable of raising great weights, men and other animals, into the region of the atmosphere and returning with safety to the earth.”33 John Morgan died in Philadelphia on October 1789, at age fifty-three. William Shippen died of anthrax in July 1808, at age seventy-one. Benjamin Rush destroyed the letters dealing with his bitter controversy with Shippen. Rush died of typhus fever 1813 at age sixty-eight.

Boston

Born in 1753, John Warren was educated at Boston Latin School, America’s first high school, and then Harvard, America’s first university. “Immediately after leaving college, he commenced the study of medicine with his brother Joseph, who had been one of the most successful practitioners in Boston.” There was little book learning. As an apprentice, “he was required to prepare medicines, spread plasters, dress slight wounds, and rise to attend calls in the night. He accompanied his instructor in his attentions on patients [and gained] experience and confidence while under the eye of the master.”34 At the start of the Revolutionary War, twenty-two-year-old John and thirty-three-year-old Joseph Warren sided with the patriots. Joseph served as president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Commissioned as a major general in the militia, Joseph chose to serve as a volunteer in the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, where he died in combat.

John served as an army surgeon in the hospital at Cambridge. When the war shifted from Massachusetts, John Warren worked in hospitals in New York and New Jersey, under the leadership of John Morgan and then William Shippen. In July, 1777, John Warren was appointed senior surgeon of the military hospital in Boston.35 He was a founder of the Boston Medical Society in 1780, the Massachusetts Medical Society in 1781, and was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

“The military hospitals of the United States furnished a large field for observation and experiment . . . as well as an opportunity for anatomical investigation.” During 1780 Warren “commenced a course of anatomical demonstrations to the medical men of the town.”36 Joseph Willard, president of Harvard University, attended Warren’s lectures and this “led to the idea of forming a medical institution to be connected with the university. The president communicated this desire to Dr. Warren, a conference was held, and he was desired to draw up the plan for such an institution . . . The whole burden of making it successful, rested upon him.”37

In developing the three-year curriculum and the rules to govern the proposed medical school, Warren sought the advice of Philadelphians Benjamin Rush and William Shippen. On September 19, 1782, the Warren plan was approved by the Harvard board of overseers. John Warren was appointed head of the medical school and professor of anatomy. Benjamin Waterhouse was appointed professor of the theory and practice of physic and Aaron Dexter professor of chemistry and pharmacology. The first medical graduates of Harvard medical school were Gilbert Pearson in 1789, then Nathan Smith, in 1790. Harvard medical school grew slowly. Twenty years later, “forty-eight young men were graduated as bachelor of medicine.” Harvard established a “library, containing many rare and valuable books donated by Ward Nicholas Boylston.”38

The Postwar Years

After the War, the New York medical school struggled to re-establish itself. King’s College was renamed Columbia University. During his first term as president of the United States, George Washington lived at 3 Cherry Street, New York. Dr. Samuel Bard was his personal physician. On June 17, 1789, Dr. Bard operated on the president to open “a very large and painful tumor on the protuberance of my thigh.” In May 1790, Washington developed pneumonia. Under Dr. Bard’s care “he continues to mend and from total despair we now have good hopes for him.”39 During 1791, Columbia College’s medical school opened with Samuel Bard as dean.

On September 23, 1783, Benjamin Rush sent a letter to William Cullen, his former teacher in Edinburgh. “One of the severest taxes paid by our profession during the war was occasioned by the want of a regular supply of books from Europe, by which means we are eight years behind you in everything.”40 In July 1797, Samuel Latham Mitchill, Elihu Hubbard Smith and Edward Miller, of the faculty of medicine at Columbia College, founded the Medical Repository, the first medical journal in the United States. The journal appeared quarterly until it folded in 1824. Samuel Mitchill served in New York as apprentice to Dr. Samuel Bard. From 1783 to 1786 he completed his medical education at the University of Edinburgh medical school. Elihu Smith and Edward Miller graduated from the University of Philadelphia medical school before moving to New York. The journal was timely because “the zeal and activity with which medical improvements are prosecuted in Europe, is fast spreading in America.” It offered “accurate and succinct accounts of general diseases, useful histories of particular cases [and] new methods of curing diseases.” The first issue reported on plagues in Athens and London, cholera in children, yellow fever, and the anatomy of rattlesnakes. Subsequent issues discussed venereal diseases, diabetes, dropsy, pestilential fever, hydroceles, madness, epilepsy and scrofulous, among many other conditions. “The Medical Repository was the first serious attempt in the United States to present the relation between science and practice.” Volume 1 of the Medical Repository attracted 265 subscribers, mainly from New York, Philadelphia and Boston.41

Into the nineteenth century

Benjamin Rush is the most remembered of the pioneers of American medical education. He was the only physician among the signors of the Declaration of Independence. He opposed slavery and was an advocate for more humane care for the mentally ill. Rush wrote Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon the Diseases of the Mind, published in 1812. He is regarded as the father of American psychiatry.

John Collins Warren and James Jackson were born at the start of the Revolutionary War. Warren followed his father as professor of anatomy and surgery at Harvard medical school. Jackson served as professor of medicine. Warren and Jackson were the founders of the New England Medical Journal. The first issue of the journal on January 1, 1812, carried a paper by Warren’s father on angina pectoris, characterized by pain around the left breast that may extend down the left arm. The pain worsens while walking, especially uphill, and quietens on standing still. Angina pectoris occurred mainly among elderly men, less in women and rarely in children. It was not yet known that angina pectoris related to coronary artery disease. In 1821, John Collins Warren as head surgeon and James Jackson as head physician, founded the Massachusetts General Hospital. On October 16, 1846, at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. John C. Warren performed the first public surgical operation on a patient under ether anesthesia. In 1856, James Jackson wrote Letters to a Young Man Just Entering upon Medical Practice, dedicated to the memory of John Collins Warren.

1 Byron Stookey, A History of Colonial Medical Education in the Province of New York (Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas, 1962), 3.

2 Genevieve Miller, “A Physician in 1776,” Clio Medica, Volume11, No.3 (October 1976), 135-146.

3 Francis R. Packard, History of Medicine in the United States (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1901), 191.

4 The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 10, ed. Leonard W. Labaree (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1959), 146–147. Benjamin Rush, “Lecture Delivered before the Trustees and Students of Medicine in the College of Philadelphia on the 28th of November, 1789,” in Joseph Carson, A History of the Medical Department of the University of Pennsylvania from its Foundation in 1765 (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston,1869), 49.

5Justin McHenry, “John Morgan vs. William Shippen: The Battle that Defined the Army Medical Department,” Journal of the American Revolution, January 28, 2020, allthingsliberty.com/2020/01/john-morgan-vs-william-shippen-the-battle-that-defined-the-medical-department/. Packard, History of Medicine, 309.

6 Carson, A History of the Medical Department, 44.

7 John Morgan, A Discourse upon the Institution of Medical Education in America (Philadelphia: Bradford, 1765). Benjamin Franklin to John Morgan, July 8, 1765, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 12, ed. Leonard W. Labaree (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1967), 203–204.

8 Packard, History of Medicine, 342-6. Franklin to Morgan, February 5, 1772, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 19, ed. William B. Willcox (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1975), 65.

9 Packard, History of Medicine, 348. William Shippen to Franklin, May 14, 1767, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 14, ed. Leonard W. Labaree (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1970), 148–149.

10 The Journal of John Morgan of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1907), 20; Packard, History of Medicine, 354. Whitfield J. Bell Jr., John Morgan; Continental Doctor (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 1965), 137.

11 John McVicar, The Life of Samuel Bard MD. LLD (New York: Paul, 1822), 38.

12 Stookey, A History of Colonial Medical Education, 38.

13 McVicar, The Life of Samuel Bard, 89, Packard, History of Medicine, 217-219, Stookey, A History of Colonial Medical Education, 53-54.

14 Whitfield J. Bell. Jr., “The Court Martial of Dr. John Shippen Jr., 1780,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences Vol. 19, No.3 (July 1964), 218-238.

15 The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), 314–316.

29 The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 30, 1 January–6 March 1781, ed. Benjamin L. Huggins (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2022), 42–43.

30 Ibid., 451.

31 Carson, A History of the Medical Department, 80.

32 Nathan G. Goodman. Benjamin Rush: Physician and Citizen, 1746-1813 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1934), 68; Carson, A History of the Medical Department, 93.

33 Francis Hopkinton to Thomas Jefferson, May 12, 1784, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 7, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953), 245–247.

34 Edward Warren, The Life of John Warren MD (Boston: Noyes & Holmes, 1874), 12-14.

35 Ibid., 144.

36 Ibid., 225-227.

37 Ibid., 243, 284.

38 Ibid., 436.

39 George Washington to James McHenry, July 3, 1789, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 3, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 112–113. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 14, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958), 429.

40 Carson, A History of the Medical Department, 85.

41Richard J. Kahn and Patricia C. Kahn, “The Medical Repository—The First U.S. Medical Journal (1797-1824),” New England Journal of Medicine vol. 337 (1997):1926-1930.

One thought on “Early Medical Education and the Revolutionary War”

As a fellow physician thank you for this excellent history and also for your article on Washingtons physician