May 2025 will bring the 250th anniversary of a unique if obscure Revolutionary war event in Charlotte, North Carolina: the much beloved, much maligned, “first” declaration of independence in the American colonies: the Mecklenburg Declaration of May 20, 1775 (or “MeckDec” as the locals call it).

The MeckDec tale and associated celebrations have ebbed and flowed for over 200 years; wildly popular in the nineteenth century, dissipating in the twentieth, resurgent in the last two decades. Professional historians have largely (but by no means unanimously) derided the historical claim that the citizens of Mecklenburg County declared independence from Great Britain, as local lore suggests. This skepticism has in no way affected the enthusiasm of local supporters in and around Charlotte. A local non-profit called The May 20th Society arranges annual commemorations, speeches and beer launches and will do so again in 2025 (and, for the sake of transparency, the author is Chairman of this organization).

Notwithstanding a great deal of disinterest or disbelief, even in the local community, about the veracity of the story, the date May 20, 1775 graces the North Carolina flag as well as the official state seal. Four sitting American presidents have visited Charlotte over the last century for the annual commemoration (Presidents Taft, Wilson, Eisenhower and Ford). North Carolina has a popular “First in Freedom” license plate, dedicated to both the MeckDec and the later Halifax Resolves. Fly through the Charlotte Douglas International airport and you may pass a bar called Captain Jack’s Tavern (named for a major protagonist in the story), which serves a popular beer called Captain Jack. A bronze 1:5 scale equestrian statue of Captain Jack himself (unveiled in 2010) stands not far from downtown along a much-trafficked greenway on what is called the Trail of History: thus far eleven bronze statues of notable county figures.[1]

The facts around the MeckDec story have been discussed and disputed for centuries, without settling the debate to the full satisfaction of either believers or skeptics. The original papers were lost in a fire in 1800, so accounts of the story rest on later eyewitness testimony. A great body of circumstantial evidence exists in favor the story, although without any original documents, critics dismiss the tale as a later misremembrance of well-intentioned but mistaken old men.

Although much new evidence has emerged in the last decade (including previously unseen pension application references), current skeptics (in my experience) usually do not have a strong foundation for their views, beyond a Wikipedia-level knowledge of the facts, and are generally not current with any new arguments or developments since William Hoyt’s book of 1907 dismissing the story as spurious.[2] By the same token, some MeckDec enthusiasts have arguably been guilty of overstating the relevance and importance of the story, even if it is true.

With that background, it seemed worthwhile to set out the basic facts of the case, and, in the interests of fairness, the arguments, pro and con, of the MeckDec saga, so that everyone can make up their own minds.

The Basic Story of the Mecklenburg Declaration & the Ensuing Controversy

Meeting on May 20, 1775 in Charlotte Towne

In the spring of 1775, the American colonies were in turmoil. Over the past decade a series of punitive and hated taxes (such as the well-known Stamp Act) and British attempts to enforce them had escalated tensions between the American colonists and the British mother country. In the Southern colonies, and in particular the central piedmont area, peopled as it was with Scots-Irish Presbyterians, animosity to English rule ran high. As British Colonial Secretary Lord Dartmouth put it in a letter to North Carolina Royal Governor Josiah Martin that summer, the colonies were in a “state of general frenzy.”[3]

In late May 1775, the leaders of Mecklenburg called a meeting to discuss how to address the deteriorating state of affairs. Col. Thomas Polk, commander of the county militia, requested a meeting of local militia leaders to be held on May 19. According to the surviving fragmentary papers of one participant, the meeting was called “to devise ways & means to extricate themselves and ward off the dreadfull impending storm bursting on them by the British Nation.”[4] The meeting was at the Mecklenburg County courthouse—a rustic, unpainted log cabin which stood atop six red brick pillars, each ten feet high, in the middle of the Charlotte town common (now the intersection of Trade and Tryon Streets).

It is not known exactly how many individuals participated in the meeting, although later accounts give the number at twenty six or so individuals. One witness later wrote:

We are not, at this late period, able to give the names of all the Delegation who formed the Declaration of Independence; but can safely declare as to the following persons being of the number, viz. Thomas Polk, Abraham Alexander, John M’Knitt Alexander, Adam Alexander, Ephraim Brevard, John Phifer, Hezekiah James Balsh, Benjamin Patton, Hezekiah Alexander, Richard Barry, William Graham, Matthew M’Clure, Robert Irwin, Zachias Wilson, Neil Morrison, John Flenniken, John Queary, [and] Ezra Alexander.[5]

Other accounts give more or less the same number and identity of participants, although there are a few discrepancies.

During the meeting a messenger arrived on horseback bringing word of the battles of Lexington and Concord, which had occurred exactly one month prior (on April 19). This news threw the meeting into chaos and confusion. One eyewitness named Joseph Graham recalled that there was “much animated discussion.”[6] John McKnitt Alexander recalled, “We smelt and felt the Blood & carnage of Lexington, which raised all the passions into fury and revenge.”[7]

The delegates decided to declare a series of resolutions dissolving their allegiance to British authority. McKnitt Alexander described the delegates as having a “free discussion in order to give relief to suffering America and protect our just & natural right[s].”[8]

In the words of Joseph Graham, “After reading a number of papers as usual, and much animated discussion, the question was taken, and they resolved to declare themselves independent.”[9]

One eyewitness named Isaac Alexander recalled:

I was present in Charlotte on the 19th and 20th days of May, 1775 when a regular deputation from all the Captains’ companies of militia in the county of Mecklenburg . . . met to consult and take measures for the peace and tranquility of the citizens of said county, and who appointed Abraham Alexander their Chairman, and Doctor Ephraim Brevard Secretary; who, after due consultation, declared themselves absolved from their allegiance to the King of Great Britain, and drew up a Declaration of their Independence, which was unanimously adopted.[10]

Maj. John Davidson testified that he was a delegate and recalled: “When the members met, and were perfectly organized for business, a motion was made to declare ourselves independent of the Crown of Great Britain, which was carried by a large majority.”[11] (Other accounts give the vote as unanimous).

According to other eyewitnesses, the delegates “formed several resolves, which were read, and which went to declare themselves, and the people of Mecklenburg county, Free and Independent of the King and Parliament of Great Britain.”[12]

Captain Jack rides to Philadelphia

Following the meeting, the committee tasked a local tavern owner named James Jack to deliver their resolutions to the Continental Congress. Jack was instructed “to go express to Congress (then in Philadelphia) with a copy of all Sd. resolutions and laws &c and a letter to our 3 members there, Richd. Caswell, Wm. Hooper & Joseph Hughes, in order to get Congress to sanction or approve them.”[13] According to Jack’s later accounts, “I set out the following month, say June.”[14]

Jack’s errand was known to the British officials. In August 1775, Governor Martin wrote to the Earl of Dartmouth in London that he had been “informed” that “treasonable resolves” had been “sent off by express to the Congress at Philadelphia as soon as they were passed in the Committee.”[15]

Jack testified: “I then proceeded on to Philadelphia, and delivered the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence of May, 1775, to Richard Caswell and William Hooper, the Delegates to Congress from the State of North Carolina.”[16] Beyond Jack’s account, no first hand record exists of Jack’s meeting with Caswell and the others, or what was said. Nor has a copy of whatever papers he delivered to them ever been found. The records of the Continental Congress do not mention Jack’s mission.

A historian named Cyrus Hunter, writing a century after the events, gave the following account of Jack’s arrival in Philadelphia:

Upon his arrival [Captain Jack] immediately obtained an interview with the North Carolina delegates (Caswell, Hooper and Hewes), and, after a little conversation on the state of the country, then agitating all minds, Captain Jack drew from his pocket the Mecklenburg resolutions of the 20th of May, 1775, with the remark: ‘Here, gentlemen, is a paper that I have been instructed to deliver to you, with the request that you should lay the same before Congress.’

After the North Carolina delegates had carefully read the Mecklenburg resolutions, and approved of their patriotic sentiments so forcibly expressed, they informed Captain Jack they would keep the paper, and show it to several of their friends, remarking, at the same time, they did not think Congress was then prepared to act upon so important a measure as absolute independence

Jack was told that Congress thought that independence was “premature.” According to Cyrus, Jack then replied:

‘Gentlemen, you may debate here about ‘reconciliations’ and memorialize your king, but, bear it in mind, Mecklenburg owes no allegiance to, and is separated from the crown of Great Britain forever.’[17]

As noted, this account, while vivid and interesting, was written much later.

The British Records

Meanwhile, there are a number of references to the events in Mecklenburg County in British records. For example, in a letter of June 30, 1775 to Lord Dartmouth, Governor Martin wrote:

The Resolves of the Committee of Mecklenburg which your Lordship will find in the enclosed Newspaper, surpass all the horrid and treasonable publications that the inflammatory spirits of this Continent have yet produced, and your Lordship may depend its Authors and Abettors will not escape my due notice whenever my hands are sufficiently strengthened to attempt the recovery of the lost authority of Government.[18]

The “enclosed newspaper” has not been found, and in fact was removed from the British archives by the U.S. ambassador to Great Britain in the early nineteenth century. This ambassador was from Virginia and a friend and colleague of Thomas Jefferson. Thought to be the Cape Fear Mercury, the newspaper has never been seen since, so it cannot be determined what resolutions were in it. The bizarre circumstances of the missing paper, and the individuals involved, have led to any number of conspiracy theories about destruction of evidence in order to protect Jefferson (whom Adams would accuse of plagiarism, of which more below).

Similarly, in August 1775, Governor Martin formally responded to the people of North Carolina in what was called the “Fiery Proclamation”:

I have also seen a most infamous publication in the Cape Fear Mercury importing to be resolves of a set of people stiling themselves a Committee of the County of Mecklenburg most traitorously declaring the entire dissolution of the Laws Government and Constitution of this country and setting up a system of rule and regulation repugnant to the Laws and subversive of His Majesty’s Government

It is beyond dispute that the locals in Mecklenburg and surrounding counties were extremely anti-English; the county was later described by the British as a “hornets nest” of rebellion. While that is not dispositive in the MeckDec debate, the mindset of the inhabitants remains interesting. By way of example, Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton noted: “It was evident, and it has been frequently mentioned to the King’s officers, that the counties of Mecklenburg and Rohan [Rowan] were more hostile to England than any other in America.”[19]

The Adams and Jefferson Debate

In April 1800, fire consumed the house of McKnitt Alexander, Secretary of the May 20 Convention and keeper of the minutes, at his estate called “Alexandriana.” The minute book with the May 19–20 convention records was destroyed. Although some of Alexander’s notes and related papers survived the fire, all original copies of the Mecklenburg Declaration were lost. No originals have ever been located (and the “enclosed newspaper” noted above removed and never seen again), so the only basis we have for knowing what it may have said, were certain undated and anonymous papers and the later eyewitness testimony (of which more later).

Around 1819, Dr. Joseph Alexander, the son of McKnitt Alexander, found among his father’s surviving papers a written account and text of the MeckDec story. He had it printed in the Raleigh Register, the state’s largest newspaper.

The story was reprinted nationally in other papers. Former President John Adams read the story and was astonished, writing to Thomas Jefferson on June 22, 1819: “May I inclose you one of the greatest curiosities and one of the deepest mysteries that ever occurred to me? It is in the Essex Register of June 5, 1819. It is entitled the Raleigh Register [Mecklenburg] Declaration of Independence.”[20] “How is it possible,” he asked rhetorically, “that this paper should have been concealed from me to this day?” He continued, “What a poor, ignorant, malicious, short-sighted, crapulous mass is Tom Paine’s ‘Common Sense,’ in comparison with this paper! . . . The genuine sense of America at that moment was never expressed so well before, nor since.”[21]

What Adams didn’t write to Jefferson, but found even more astonishing, was how similar many of the passages of the MeckDec were to the National Declaration of Independence, including language such as “dissolve the political bands which have connected us to the mother country” and “our lives, our fortunes, and our most sacred honor.” Adams was convinced this was more than a coincidence. He believed Jefferson must have seen the MeckDec, and copied passages of it into the famous July 4 document.

On July 15, Adams wrote to a friend, Rev. William Bentley:

I was struck with so much astonishment on reading this document, that I could not help inclosing it immediately to Mr. Jefferson, who must have seen it, in the time of it, for he has copied the spirit, the sense, and the expressions of it verbatim, into his Declaration of the 4th of July, 1776.[22]

Jefferson refused to take Adams’ bait, and responded with a lengthy, well-argued and reasonable analysis of the Mecklenburg document. Jefferson replied, “What has attracted my peculiar notice, is the paper from Mecklenburg county . . . And you seem to think it genuine. I believe it spurious.” Why, Jefferson further, argued, had no one ever heard or acted on this Mecklenburg Declaration?

Would not every advocate of independence have rung the glories of Mecklenburg county, in North Carolina, in the ears of the doubting Dickinson and others, who hung so heavily on us? Yet the example of independent Mecklenburg county, in North Carolina, was never once quoted.

Jefferson concluded by stating that although there was not sufficient evidence that the MeckDec was true (at least in his view), he would keep an open mind, writing:

Nor do I affirm, positively, that this paper is a fabrication; because the proof of a negative can only be presumptive. But I shall believe it such until positive and solemn proof of its authenticity shall be produced. For the present, I must be an unbeliever in the apocryphal gospel. [23]

The battle lines were now set between Adams vs. Jefferson, the MeckDec’ers vs. skeptics. The hunt for evidence was on. A number of papers and books were written, pro and con, throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century about the “Mecklenburg Controversy.”

The Mecklenburg Resolves of May 31, 1775 are Discovered

Things got more complicated in 1838 when a researcher named Peter Force discovered a series of resolutions from a committee in Charlotte-Town in an old newspaper dated in the summer of 1775. The preamble of the Resolves read:

Whereas by an Address presented to His Majesty by both Houses of Parliament, in February last, the American colonies are declared to be in a state of actual rebellion, we conceive, that all laws and commissions confirmed by, or derived from the authority of the King or Parliament, are annulled and vacated, and the former civil constitution of these colonies, for the present, wholly suspended. To provide, in some degree, for the exigencies of this county, in the present alarming period, we deem it proper and necessary to pass the following Resolves.[24]

Four resolutions followed. The first announced that “all commissions, civil and military, heretofore granted by the Crown” were “null and void” and “the constitution of each particular colony wholly suspended.” The second delegated, or “invested,” “all legislative and executive powers” to the “Provincial Congress of each Province,” and declared “no other legislative or executive does or can exist, at this time, in any of these colonies.” These become known as the “Mecklenburg Resolves” to differentiate them from the “Mecklenburg Declaration.”

These resolutions, twenty in number, did not look or read like what the witnesses recalled the Mecklenburg Declaration as looking or reading like. They were dated May 31, when by nearly all accounts the MeckDec had been made on May 20. They were also longer and more bureaucratic in nature. Nowhere do they say that the county “dissolved the political bands” with Great Britain nor was “free and independent” as the witnesses had said and the other papers had suggested.

It was not clear what these Mecklenburg Resolves were, or what they meant. But it was clear that they were at least somewhat inconsistent with the story as told by the eyewitnesses, whatever that implied.

The Moravian Journals Are Discovered

Returning from Philadelphia, Captain Jack stopped in Salem, North Carolina, and spoke with Traugott Bagge, a merchant, about the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Bagge was a Moravian, a German speaking sect in the area. In the German language Moravian archives written in 1783 (but not discovered and translated until around 1900), Bagge wrote:

I cannot leave unmentioned at the end of the 1775th year that already in the summer of this year, that is in May, June, or July, the County of Mecklenburg in North Carolina declared itself free and independent of England, and made such arrangements for the administration of the laws among themselves, as later the Continental Congress made for all. This Congress, however, considered the proceedings premature.[25]

To many, the Moravian journals were the final conclusive proof that the story must be true. Albeit circumstantial in nature, there were too many MeckDec coincidences for it to be a fabrication, as Jefferson had suggested.

Evidence & Arguments in Favor of the Mecklenburg Declaration

The Governor’s Report

In 1829, the North Carolina General Assembly created a select committee to settle the controversy once and for all. The committee reached out to witnesses in Mecklenburg and surrounding counties and as far afield as Georgia and Tennessee for any surviving participants or observers from the meetings in May 1775, such as Capt. James Jack, Gen. Joseph Graham and Maj. John Davidson. They produced a thirty-two-page report on their findings, published by the Assembly in 1831. Its preface was written by Gov. Montford Stokes, so it is known as the “Governor’s Report.” Davidson was the only surviving participant (other than Captain Jack, who was not an actual signer/delegate but an important part of the story).

The Governor’s Report contained a dozen or so affidavits in favor of the story, all largely consistent in fact and theme. Moreover, the witnesses were not random folks off of the street, but credible and influential people in the community. Even Governor Stokes himself claimed to have personally seen a copy of the Mecklenburg Declaration before it was lost in a fire, noting: “this copy the writer [Stokes] well recollects to have seen in the possession of Doct. Williamson, in the year 1793.”

Another witness, William Polk, first cousin of President James K. Polk, was a bona fide Revolutionary war hero and leading North Carolina businessman. Polk, according to the Governor’s Report, “was present, heard his father [Thomas Polk] proclaim the Declaration to the assembled multitude; and need it be inquired, in any portion of this Union, if he will be believed?”

But the star witness of the Governor’s Report was Gen. Joseph Graham. His written testimony about the events of May 1775 ran nearly two pages and was quite detailed. He was not just any eyewitness, but a prominent local figure. After enlisting as a private in May 1777 in the 4th North Carolina Regiment, Graham fought at the battles of Stono, Rocky Mount, Hanging Rock, and a number of lesser skirmishes. Most notably he assisted in contesting the British advance into the crossroads town of Charlotte in September 1780, where he was sabered nearly to death in hand-to-hand combat with the British Legion. After the Revolution Graham became a leading industrialist and civic leader in the region. His account of the MeckDec story is one of the best known: “I was then a lad about half grown,” he later recalled, and “was present on that occasion [as] a looker on.”

Graham remembered:

The news of the Battle of Lexington, the 19th of April preceding, had arrived. There appeared among the people much excitement . . .

After reading a number of papers as usual, and much animated discussion, the question was taken, and they resolved to declare themselves independent. One among other reasons offered, that the King or Ministry had, by proclamation or some edict, declared the Colonies out of the protection of the British Crown; they ought, therefore, to declare themselves out of his protection, and resolve on independence . . .

It [the Mecklenburg Declaration] was unanimously adopted, and shortly after it was moved and seconded to have [the] proclamation made and the people collected, that the proceedings be read at the courthouse door, in order that all might hear them. It was done, and they were received with enthusiasm. It was then proposed by some one aloud to give three cheers and throw up their hats. It was immediately adopted, and the hats thrown. Several of them lit on the court house roof. The owners had some difficulty to reclaim them. The foregoing is all from personal knowledge.

The eyewitness testimony was compelling, and the witnesses themselves beyond reproach. Many were decorated veterans of the American Revolution. Two of them were ordained Presbyterian ministers. The following gives some flavor of their testimony:

When the members met, and were perfectly organized for business, a motion was made to declare ourselves independent of the Crown of Great Britain, which was carried by a large majority. [John Davidson][26] On the 20th they again met, with a committee, under the direction of the Delegates, had formed several resolves, which were read, and which went to declare themselves, and the people of Mecklenburg county, Free and Independent of the King and Parliament of Great Britain. [George Graham, William Hutchinson, Jonas Clark and Robert Robinson][27]

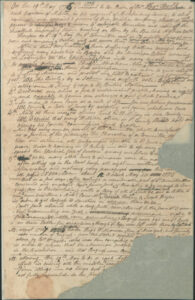

Surviving Papers of John McKnitt Alexander

Although any original copies of the MeckDec were lost in the 1800 fire, a number of secondary papers survived. One was given to partisan leader (and later North Carolina governor) William R. Davie (called the “Davie Copy”). A second are some surviving papers of McKnitt Alexander himself. These fragmentary and rough notes, although undated and torn, communicate a clear picture of the events of May 19–20. For example, “after a short conference about their suffering brethren besieged and suffering every hardship in Boston and the American Blood running in Lexington,” McKnitt Alexander wrote, “the Electrical fire flew into every breast,” and “by a solemn and awfull vote, [we] Dissolved (abjured) our allegiance to King George and the British Nation.”[28]

Other Fragments in Favor

A recent find is a reference to the MeckDec in the April 14, 1801 Raleigh Register and North-Carolina Weekly Advertiser, which recorded a gathering of “the Republican citizens of the village of Charlotte, in Mecklenburgh County” in celebration of the election of President Jefferson. The gathering was “convened at the house of Mrs. M’Combs on the 17th ult.” and had a series of toasts, including: “10. The citizens of Mecklenburg, being the first in their declaration of Independence, may they ever be the first in resisting usurpation by defending their civil righst [sic].”[29] This is the earliest reference to MeckDec currently known.

On Wednesday, March 2, 1825, the Marquis de Lafayette visited in Raleigh as part of his famous American tour. Col. William Polk, the son of Col. Thomas Polk, a leading figure in the MeckDec story, was Lafayette’s principal host during this visit. In the course of ceremonial toasts, Lafayette raised his glass to “The State of North Carolina, its Metropolis, and the twentieth of May, 1775, when a generous people called for independence and freedom, of which may they more and more forever cherish the principles and enjoy the blessings.”[30] Did Lafayette have independent knowledge of the MeckDec story, or was he responding to something his host Polk had told him?

Evidence & Arguments Against the Mecklenburg Declaration

Evidence of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence—or put differently, the lack of written, conclusive evidence—is the fact that no original copy of the document exists. Skeptics of the story allege that without the original document, the story is unproveable. The basis of the text rests on the copy found by Dr. Alexander; this text is anonymous, undated and of unclear origin. The other extant documents—such as the Davie Copy or McKnitt Alexander’s “rough notes”—suffer similar evidentiary failings; i.e, they are torn, undated and of undetermined origin.

The only document that exists from the period that is of undebatable provenance is the Mecklenburg Resolves. And these fall short of a declaration of independence and are similar to other anti-British resolutions of the period.

Consequently, the skeptics believe the only authentic document of the period is the Mecklenburg Resolves. The critics argued that when the witnesses gave their testimony in 1830 in connection with the Governor’s Report, in their old age they conflated in their minds a true event (the Mecklenburg Resolves) with a fictitious one (the Mecklenburg Declaration). In short, the entire MeckDec story is simply a case of mistaken identity. To this day, whether the Mecklenburg Resolves are a part of the overall story or the “real” document itself, remains the crux of the controversy.

In the late eighteenth and early twentieth century, a few leading historians came out against the MeckDec story, with repercussions that continue to this day. The seminal “anti” work was published in 1907 by William Henry Hoyt. His work, entitled The Alleged Early Declaration of Independence by Mecklenburg County . . . Is Spurious began: “Since it was first brought to the attention of the general public in the year 1819 the declaration of independence which is alleged to have been issued on May 20, 1775, by a convention held in Charlotte . . . has been the subject of the most mooted question and acrimonious controversy of the history of the American Revolution.”[31]

Hoyt marshaled an impressive and seemingly comprehensive array of counter-arguments, theories and criticisms against the witnesses. He argued forcefully that it was inconceivable that any colonists would have desired independence in the summer of 1775.

He pointed out that no one nationally, regionally, or even, it appeared, locally had heard of the fabled declaration at the time which indicated that there could not truly have been a declaration of independence in the area.

Hoyt examined all of the existing documents and was the first to point out that McKnitt’s “rough notes” could have been (indeed, likely were) written in or sometime after the year 1800. Hoyt then stated that the evidence was generally consistent with the Mecklenburg Resolves of May 31 and concluded this was the only true paper.

We may reasonably presume that after July 4, 1776, the May 31st resolves were loosely called a declaration of independence by many persons, and that in the course of time, as their phraseology and terms were forgotten, and the number of their surviving authors diminished, they were looked back upon in Mecklenburg county generally, and to some extent in the surrounding section of country, as a formal declaration of independence. In the light of our study of the records of 1775 . . . this supposition becomes a certainty.[32]

Other historians took their cue from Hoyt’s work and piled on. The most aggressive was A. S. Salley, Jr, a colleague of Hoyt’s, Secretary of the South Carolina Historical Commission and a proud South Carolina patriot. Using Hoyt’s work as a point of departure, Salley wrote a blistering article in 1908 in the American Historical Review concluding that “the facts shown by the resolutions of May 31, 1775, and other authentic records preclude the possibility of any such action having been taken on May 20, 1775.”[33]

Salley pointed out niggling inconsistencies in the testimony as proof that the stories were inconsistent or exaggerated. For example, some witnesses remembered that Adam Alexander had called the meeting (as the documents seemed to indicate), while others said it was Thomas Polk. Similarly, he pointed out that Captain Jack claimed that when he passed through Salisbury in June 1775 “the General Court was sitting.” Because this must have been the first week of June, “it is evident that Jack carried the resolutions of May 31” and not the Mecklenburg Declaration.[34] He also noted the identity of the number of attendees at the meeting varied in many of the accounts.

Conclusion

As the above hopefully demonstrates, while reasonable minds can disagree about the arguments themselves, no one can dispute that a great body of evidence regarding the MeckDec exists; far more than the casual dismissiveness of many who superficially engage the story would suggest. Historians and enthusiasts on both sides of the issue will never conclusively prove or disprove the case, at least to everyone’s satisfaction. Thus, the MeckDec controversy, dating back to Adams and Jefferson, grinds on and will not be resolved anytime soon, if ever, which candidly is part of the fun. At least a thorough understanding of the facts and current state of the arguments benefits everyone in making their own judgment on the veracity of the centuries’ old MeckDec controversy.

[1] See www.charlottetrailofhistory.org/.

[2] William Henry Hoyt, The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence by Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, on May 20th, 1775, is Spurious (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907).

[3] William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth to Josiah Martin, May 3, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, digital edition, 9:1240-1242.

[4] John McNnitt Alexander, “Rough Notes,” in the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence Papers in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (SHC).

[5] The Declaration of Independence by the Citizens of Mecklenburg County, published by the Governor under the authority and direction of the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina (Raleigh, Lawrence & Lemay, 1831), 25 (Governor’s Report).

[6] Ibid., 19.

[7] Alexander, Rough Notes, SHC

[8] Ibid., SHC.

[9] Governor’s Report, 19.

[10] Ibid., 26.

[11] Ibid., 27.

[12] Ibid., 23-24.

[13] Alexander, Rough Notes, SHC.

[14] Governor’s Report, 16.

[15] Josiah Martin to William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth, June 30, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, digital edition, 10:48.

[16] Governor’s Report, 16.

[17] Cyrus L. Hunter, Sketches of Western North Carolina (Raleigh, Raleigh News Stream, 1877), 68-69.

[18] “Proclamation by Josiah Martin concerning the election of delegates to the Provincial Congress of North Carolina and militia officers and loyalty to Great Britain,” August 15, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, digital edition, 10:141-151.

[19] Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (North Stratford, NH: Ayer Company Publishers, Inc., 2007), 168.

[20] Lester J. Cappon, ed., The Adam-Jefferson Letters: The Complete Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and Abigail and John Adams (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 542.

[21] Ibid.

[22] “Adams letter to William Bentley, dated July 15, 1819,” in John Adams, The Works of John Adams (Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1856), 10: 381.

[23] Adams-Jefferson Letters, 543–544.

[24] The preamble plus four resolves were from the Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), December 18, 1838. The text of the Resolves quoted in this chapter is from the original version of The South-Carolina Gazette; and Country Journal of June 13, 1775 (No. 498) in the Charleston Library Society, Charleston, SC.

[25] Adelaide L. Fries, The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, As Mentioned in Records of Wachovia (1907) (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1907), 3.

[26] Governor’s Report, 27.

[27] Ibid., 23-24.

[28] SHC.

[29] Raleigh Register and North-Carolina Weekly Advertiser, April 14, 1801, with thanks to Rebecca Fried for finding this information.

[30] Raleigh Register, March 8, 1825.

[31] Hoyt, Mecklenburg Declaration, iii.

[32] Ibid., 112.

[33] A. S. Salley, Jr., “The Mecklenburg Declaration: The Present Status of the Question,” The American Historical Review, 13, no. 1 (1908), 29.

[34] Ibid.

Recent Articles

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

Recent Comments

"The 100 Best American..."

I would suggest you put two books on this list 1. Killing...

"Dr. James Craik and..."

Eugene Ginchereau MD. FACP asked for hard evidence that James Craik attended...

"The Monmouth County Gaol..."

Insurrectionist is defined as a person who participates in an armed uprising,...