Richard Cranch was born on October 26, 1726, in Kingsbridge, Devon, England, the youngest of seven children.[1] The Cranch family had lived in Devon for centuries and had been involved in woolen manufacture for many years. Cranch was apprenticed as a wool-card maker, and emigrated to Boston on the ship Wilmington, arriving on November 2, 1746. Accompanying him were his sister Mary (1720-1790) and her husband Joseph Palmer (1716–1788), who had married on April 4 just before the voyage to Boston. Palmer was ten years old than Richard and had some wealth, so he may have paid for Richard’s passage.[2]

Cranch was a voracious reader and a self-taught amateur scholar who was eager to share his knowledge with friends. He read widely, particularly religion, and was regarded as an authority on biblical prophecies and the Antichrist. In 1752, Cranch left Boston due to smallpox outbreak sweeping the city and settled in the North Parish of Braintree (current-day Quincy), eight miles southeast of Boston.

In 1752, Cranch and Joseph Palmer, his brother-in-law purchased seventeen lots of property in Braintree in shed-neck area, now called German-town, and constructed buildings for four businesses: chocolate milling, processing spermaceti whale oil and candle making, glassmaking, and stock weaving.[3] Only information on the candle and glassmaking businesses is known, and both enterprises were only modestly successful as they had difficulty raising capital, finding trained employees, and distributing their products. It was difficult establishing colonial industries, as the English crown strongly opposed them and wanted the colonies to supply England with raw materials and sell them finished goods in return.

In 1755, Cranch met and became a life-long friend of John Adams.[4] Cranch moved to Weymouth, six miles southeast of Braintree, after his courtship with Eunice Paine, sister of Robert Treat Paine, a good friend of Cranch, ended when the Paine family experienced a financial reversal and there was no money for her dowry and their marriage. In January 1759, Cranch began courting Mary Smith, oldest daughter of Rev. William Smith, pastor in Weymouth.[5] In July Cranch invited John Adams to come with him to Weymouth and introduced him to Abigail Smith, Mary’s younger sister. John and Abigail did not hit it off immediately, but their romantic interest grew slowly over time.[6] In October 1762, Richard Cranch married Mary Smith and in October 1764, John Adams married Abigail Smith.

Abigail Adams had tremendous respect and appreciation for Cranch as he introduced her to many classical books. At this time, women had very few educational opportunities and the books Cranch provided her opened her eyes and inquisitive mind.[7] Abigail was a prolific letter writer, and much of the Cranch family’s activities and financial difficulties are revealed in letters exchanged between Abigail and her sister Mary, and her husband John.

Both John and Abigail Adams knew that Cranch had a poor business aptitude. John recorded in his diary incidents reflecting Richard’s poor decisions. In one case, he overpaid for an old chaise (carriage) and a horse, and was badly cheated on. John warned him against both purchases and wrote multiple negative comments about them in his diary. He was particularly critical of the horse purchase, writing that Cranch “Buying the Horse was a Piece of ridiculous Fopery, at this time,” since “he had no Occasion for one.”[8]

Cranch became interested in watch and clockmaking shortly after he arrived in Boston, but had no formal training. He acquired four horological books, and became acquainted with clockmaker and watchmaker Gawen Brown when he emigrated from England to Boston in 1749.[9]

On October 9, 1765, Mary Cranch Palmer, Cranch’s sister, wrote to her sister-in-law Mary Smith Cranch after learning of Cranch’s plan to move his family from Braintree to Salem. The letter shows that Palmer correctly understood that this business venture might not work out well:

As some impertinent Business or accident continually hinders me from an oppertunity of talking with you, I think I must write—I dont like this ugly Story of your going to Salem; I have thot. of nothing so much for a week past as about this, and the more I think of it, the more I dislike it—It hurts me to think that my Brother should have labour’d so much about his House & Garden and almost finish’d it so genteel and pretty and then leave it before he reaps the Fruit of his Labour, and He have some Fatigue to go thro’ again upon an uncertain prospect for it is not certain that he will better his circumstances by a remove—as to the Watch Business I see no room to doubt but that in the course of a few years he will find it increase here [Braintree] to as much as he can do—and as to the Scheme of Trading its likely that the times will grow worse and worse for Shopkeepers, and as he has not a Stock of his own, to do any thing considerable he must set up on Credit, and when he finds himself in Debt for Goods, and money growing Scarcer every day as its most probable he will not be able to make the returns in time, and this will Sink his Spirits and impair his health, which depends very much on tranquility of mind . . . Pardon my honest zeal and believe me your Sincere & affectionate Friend & Sister Mary Palmer.[10]

Nonetheless, in early 1766 Cranch moved his family to Salem, a small prosperous seaport city North of Boston, and opened a watch repair business. Mary Cranch Palmer’s concerns proved correct. The business’s failure might not have entirely Cranch’s fault; there were no successful watch repair businesses in Salem until 1840s.

In October 1767, he moved his family to Boston and opened a watch repair business on Hanover Street there.

In March 1769, he acquired his daybook (Figure 2) and recorded watches that he took in for repair. He repaired almost 4,000 watches from the Spring 1769 to November 1774 when the daybook was full. Besides repairing watches and clocks, he retailed watches, clocks, and miscellaneous items. Cranch had a significant and diverse clientele of approximately 1,000 customers. Most of his clients were wealthy and influential Bostonians; others were less well-known individuals living in the Boston area and neighboring towns. Cranch was well connected within the community, and he was acquainted with several Harvard College presidents, professors, ministers, and local business leaders. That his customer base was made up of primarily affluent members of society is not surprising, as verge watches were an expensive luxury item, so only wealthy individuals could generally afford them. I have identified approximately 250 of his customers. Many of Cranch’s customers traveled—or sent their watches—fifteen to fifty miles (one or two days) from the many towns in eastern and southeastern Massachusetts, western Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire and Rhode Island.

One verge pocket watch movement signed “Richd Cranch Boston 501” (Figure 3) has been identified in a Coin Silver case. This important watch was donated to the Massachusetts Historical Society by Cranch historian Robert D. Mussey Jr. after he purchased it from a watch dealer. Provenance information included with the watch indicated that it was carried by Gen. Bernardus Montross during the Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

In addition to watches, Cranch sold and repaired clocks. A tall clock has been identified recently with a unique eight-day brass movement. The movement is fitted with a composite brass dial with an attached cartouche signed “Richd Cranch Boston” (Figure 4). While there are many references that Cranch worked as a clockmaker and made clocks, this clock confirms that he made at least one and it has survived.

Approaching Revolutionary War

By November 1774, Cranch had filled his daybook, but he continued his watch repair business in Boston. The influx of more British soldiers hurt the business environment because many residents fled from Boston with their arrival. By 1775 the political and economic climate in Boston was becoming untenable. The British had shut up the port and the Coercive Acts had a stifling effect on business. It was becoming dangerous for his family. The Cranches sent their children out of Boston to greater safety in Weymouth. Many other families fled Boston altogether for safety into the outlying towns.

On March 29, 1775 Mary Cranch wrote to her daughter Elizabeth (“Betsy”) who was living in Weymouth with her Smith grandparents who were preparing her for confirmation. Mary told her daughter how precarious and dangerous life was for Boston citizens in early 1775:

My dear Betsy,

I thought when I came home yesterday that we would have been innoculated today, but the town has thought best to try once more to prevent the distemper [smallpox] spreading. Such a state of suspense is almost too much for me. We are in great danger. There is a woman who has it just below the mill pond. We can see the flag. I dare not stir out . . . I left her so poorly that it made me very dull. I was very sorry I did not stay all night for when I got to your aunt’s I found nobody at home. They did not come until the evening and Mr. Adams did not set out till nine of the oclock yesterday morning. I found all well at home, which makes me very thankful. Every day we have so much to be thankful for and I hope my dear you don’t forget to acknowledge your gratitude for the favors you receive . . . I committ you to the direction of Heaven, my dear Betsy, with the greatest affection your friend and mother, Mary Smith Cranch.[11]

Richard and Mary fled from Boston on April 12, 1775, moved to Braintree, and rented the Verchild house there.

On April 18, 1775, Nathaniel Cranch, one of Richard Cranch’s nephews, wrote from Boston to his uncle-in-law James Elworthy in London who was acting as his purchasing agent there. The letter discussed mostly their business activities, and Nathaniel Cranch was replying to Elworthy’s concerns regarding bill payments and their account books. He then commented on the gloomy current business situation that was at a complete standstill due to the port being blocked and British soldiers searching and harassing people leaving Boston. He noted that many residents had fled and confirmed that Richard Cranch and his family had just left Boston for Braintree.

Dr Cousin/

Yours of Jany 26th last, came to hand about a week since, acknowledging the rect & payment of our last Bill . . . you desire us to examine our books with you’re a/c, the only mistake I find is an Omission of 2/ wch in your Letter of March 7th 1774, you mention as paid for insurance

Our prospect at present seems very gloomy on this dovoted Capital, surrounded by Land & Water with every Hostile appearance, repeated insults offerd to the innocent inhabitants & no means of redress, Numbers of the inhabitants have already left the Town & among the rest our Worthy & Beloved Uncle [Richard Cranch] with his Family to Braintree, not far from Uncle Palmers —

Business in a great measure at a Stand, the Port being blockd up & the only Passage by land out of the Town, subject to the insolence of the Soldiery plac’d there as a guard [letter does not continue, part appears to be missing][12]

Later Nathaniel Cranch attempted to move his business goods out of Boston, and British soldiers stole all his goods (£300 worth) and it financially devastated him.

Revolutionary War

After skirmishes at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the British military was trapped in Boston by colonial militia that loosely controlled the surrounding areas. The conflict stopped importation of all civilian goods, particularly any watch repair materials for Cranch.

Initially Cranch advertised that he moved his watch repair business to Braintree, but as the war progressed customers had limited funds for watch repair. Mary and Richard Cranch had to find new ways to support themselves financially: they took in borders, Richard tutored sons of wealthy friends to attend Harvard, Mary had a small dairy herd that she milked, and in 1777 Cranch purchased a nearby farm. The farm was an expensive purchase and he had difficulty farming it as he got older; he eventually sold it to John Adams in 1802.

In 1780, Harvard College awarded Cranch an honorary Master of Arts degree and listed him as a member of Harvard’s graduating class of 1744. In 1781, he was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in recognition of his prominent status in Massachusetts.[13]

Braintree citizens elected Cranch to serve in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1780 to 1782, and in the Massachusetts Senate in 1785. He also served in the Constitutional Conference in 1788. John Adams strongly recommended that he seek nomination to serve as a judge of the Court of Common Pleas, the main trial court in Massachusetts for everyday cases. Cranch submitted his name and served in the court from 1779 to 1808, until his health declined.[14] No records of his decisions or court cases have survived.[15]

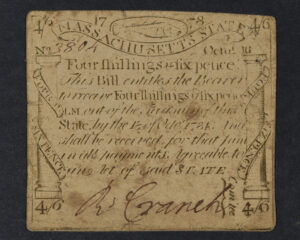

In 1779 and 1781, Thomas Dawes and Richard Cranch were authorized to sign paper currency notes issued by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the purpose of raising money for the Revolutionary War.[16] A note signed by Cranch is illustrated Figure 6.

The watch repair business was difficult leading up to the Revolutionary War and Cranch struggled to support his family financially for many years. During the war, he was employed by the State of Massachusetts, but he did not always receive a salary as the state struggled to raise enough money through taxes during the war. By 1786, the state government owned Cranch over £300 in back wages.[17] The Massachusetts State government finally paid him in securities that were worth only a fraction of the printed face value.[18] Abigail Adams was aware of her sister Mary Cranch’s troubled financial situation, and she knew that she couldn’t ask her husband John if he could help find Cranch a patronage federal government job. She and Mary kept an account of how much they owed each other. Abigail knew Mary owed her over ten pounds, so they reviewed their account and Abigail forgave Mary’s debt.[19]

No correspondence from Richard Cranch has survived mentioning the delays in receiving payment for his government, but in a letter from his wife Mary to Abigail Adams she bitterly complained about the delayed payment. On September 24, 1786, she wrote:

My dear sister,

The People will not pay their Tax, nor their debts of any kind, and who shall make them? These things affect us most severly. Mr Cranch has been labouring for the Publick for three or four years without receiving Scarcly any pay. The Treasury has been So empty that he could not get it, and now my Sister there is not a penay in it. The Publick owe us three Hundred pound and we cannot get a Shilling of it, and if the People will not pay their Tax how Shall we ever get it.

An attendenc upon the court of common pleas [by Cranch as judge] was the only thing that has produc’d any cash for above two year part of this always went to pay Billys [William Cranch’s] quarter Bills. If we had not liv’d with great caution we must have been in debt, a thing I dread more than the most extream Poverty. Mr Cranch is very dull, says he must come home and go to watch mending and Farming and leave the publick business to be transacted by those who can afford to do it without pay. What will be the end of these things I am not Politition enough to say, they have a most gloomy appearence.[20]

While John Adams was away either in Philadelphia serving in the Continental Congress or while in France, Netherlands, and England, Cranch wrote numerous letters to him. Many of his letters informed Adams about political activities in Boston or the progress of the war. Occasionally he proposed money-making schemes that Adams wisely never responded to. A typical example is in an April 26, 1780, letter where Cranch detailed war activities and political events, then repeated a scheme he had proposed in a January letter:

I would beg leave to mention to you that if any of your Mercantile Friends should be willing to become Adventurers to America in that way, I should be very glad to serve them in disposing of any Merchandize that might be consign’d to me. I am oblig’d to keep in my hands part of a very good Warehouse built with brick and cover’d with Tile, on the Town Dock in Boston, where I could store the Goods without Expence of Truckage, and would transact the Business on the most reasonable Terms.

P.S. I mentioned in last that it was probable that Borland’s Estate [Vassall-Borland house built by Leonard Vassall] in Braintree would be to be sold long by Order of the Government: should that be the case I should be glad to buy it if I could without selling my own Farm that joins upon it and makes it so very convenient for me. I should therefore be glad to know from you, by the first Opportunity, whether if I should be able to purchase that Place for about four or five Hundred Pounds Sterling you would let draw [on yo]u for that sum, on Mortgaging the Place to you for security of Payment? Your Answer either to Sister Adams or to me would greatly oblige, ut supra.[21]

Cranch continued that his nephew Nathaniel died by accident walking up Boston neck where he fell and hit his head on a rock. There is no evidence that Adams replied to Cranch’s proposals.

Cranch used his position on the “Committee of Sequestration,” which had been appointed to auction off confiscated Tory properties, to rent the Vassall-Borland House for a five-year term. Cranch was living in the Verchild House, but was unable to obtain legal title to the property so he could purchase it. He thought if he could secure funding, that he would buy the nearby Vassall-Borland House but he was again unsuccessful. While he rented the Vassall-Borland property, he cut down so many trees on the property that he was accused of “laying of waste and strip.” Braintree town citizens lodged a complaint against him over the trees at the next town meeting. As a result, Cranch moved back into the Verchild House. His reputation was severely tarnished by his using his committee position to rent the Vassall-Borland House and then cutting down so many trees on the property.[22]

Early Post Revolutionary War

By early 1783, the tensions between the colonies and England appeared to have relaxed as peace negotiations were underway. On June 20 Cranch wrote to his nephew, John Cranch, Attorney at Law in Axminster, Devon, England, the first opportunity he had to do so since the start of the war. He wrote,

By your Friend and Townsman Mr Tho’ Hopkins . . . I have had the Happiness of hearing directly from you which was peculiarly agreeable after so long an Interval of so disagreeable a kind as has taken place since I have the pleasure of Receiving a Letter from you last. I have carried Mr. Hopkins to my family & Friends at Braintree abt. 10 Miles from Boston where I have lived ever since the War. He appears much pleased with the Country.—tho’ America . . . Yet we have Liberty! A Friend of mine in whome I can depend, who lives in N. Carolina, inform’d me that great Numbers have remov’d from that State above a thousand Miles back into the wilderness, to begin new Settlements and that the Lands in those parts were the richest that had ever yet been found in America.[23]

On April 12, 1784, he wrote to his nephew James Elworthy in London regarding financial difficulties in Massachusetts after the war.

I suppose you have heard before now from all quarters, what an Inundation of Goods of every kind was pushed into America immediately on the Cessation of Hostilities from all parts of Europe. This overstock of Goods occasioned Sales to be very dull and low so that vast quantities of them were sold below he prime cost. This unforeseen and unexpected Event made it prudent for me to store most of your Adventure for some time, in hopes that Goods will fetch a better Price in the Spring and Summer. I have sold some of your Goods on credit where I thought I could do it without Risque. I have found the same difficulty in disposing of the Watches and other Articles that you was so kind as to procure for me on my order. I cannot sell them at present for ready Money unless I would sell them for little or no profit . . .

I expect this Letter will be deliver’d to you by my Friend Mr Prentice Cushing, a young gentleman that serv’d his time with me in the Watch-maker’s Business. He behaved himself all he time that he lived with me, and since he left me, in such a manner as does honour to himself and gives great pleasure and satisfaction to his Friends. He is he Son of the Revd. Jacob ‘Cushing a very worthy and respectable Clergyman of the Town of Waltham near Boston . . . I am dear Sir, with the kindest Regards to your dear Partner and little ones, your affectionate Uncle, Richard Cranch.[24]

Post Revolutionary War

Richard Cranch wrote to John Adams on May 24, 1787:

My Dear Bror.

I herewith send you the News-Papers by which you will see the state of our publick proceedings. Our most excellent Governor Mr. Bowdoin is to be left out this Year—Mr Hancock will doubtless succeed him. Strenuous efforts have been made at the present Election to get a Genl. Court that will suit the minds of the Insurgents and their Friends . . .

Our excellent Friend Doctr. Tufts is one of them. I am left out—the ostensible reason is my belonging to the Court of Com: Pleas, which Court the Populace want to have abolished, and many People now pretend that it is inconsistant with the spirit of the Constitution that any Justice of that Court should have a Seat in the Legislative Body or Council, and they are generally left out this year. Cranch.[25]

The political rules had changed, so Richard Cranch couldn’t serve in both General Court (legislature) and the Court of Common Pleas (judicial). The separation of power concept was being created with the new proposed federal government constitution. Its concept of three separate branches of government, the executive, legislative, and judicial, probably helped to drive this change.

By 1788, Cranch had only his governmental work as Judge of the Court of Common Pleas along with the farm supporting to support his family. The Boston area’s economy was slowly recovering from revolutionary war, so he decided to formally resume his full-time watch repair business. He placed an advertisement in The Independent Chronicle on March 18, 1788, and two days later in The Universal Advertiser:

Richard Cranch—The Subscriber having been obliged for several years past, to lay aside the Watchmaker’s Business on account of the public employments, in which he was then engaged; now informs the public, that he has resumed his former business, and carries it on at his house near the Episcopal Church, in Braintree: And he asks leave particularly to inform such of his friends in Boston, as were his customers when he carried on the watchmaker’s business in that metropolis, that if any of them should now incline to have their Watches done by him, they may be accommodated by leaving them with Mr. James Foster, in Cornhill, (next door to Mr. Fleet, the printer) who will take charge of them, and to when they will be returned, as soon as they are done. Richard Cranch[26]

In late 1792, Cranch wanted to acquire some watches to retail, so he contacted his nephew James Elworthy who located a watch retailer in London and arranged to purchase some watches for Cranch in the spring of 1793.

John and Abigail Adams strove to help the Cranches financially over the years. John was concerned that if he nominated Cranch for a government position it might be viewed negatively by others as nepotism, so he resisted it. He found an opportunity in 1793; when the new Town of Quincy was created, he was able to arrange to have Cranch appointed as U.S. Postmaster in the town.[27] It only provided a small income for Cranch. A letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams on April 30, 1794 inquired whether Cranch had opened his post office.[28]

Cranch had experienced a number of serious illnesses throughout his life, but he always recovered under Mary’s dutiful care. In early 1811 Mary’s health took a serious decline and it became a roller coaster—she would decline to almost dying and then recover, and then decline again. Seeing his wife, who had been their rock, so seriously ill took a serious mental and physical toll on Cranch.

In September 1811, Richard Cranch Norton, Cranch’s grandson, accompanied the two sons of William Cranch, Cranch’s son, from Washington, DC, to Braintree so they could attend Rev. Peter Whitney’s school. While there, he wrote a series of letters to Cranch’s son documenting the final days of both Richard and Mary Cranch’s lives. On October 12 Cranch appeared to have had a stroke, as he lost his ability to speak and had difficulty getting around. He passed away on October 16. Mary peacefully passed away the following day.

On October 19 Rev. Peter Whitney preached an eloquent funeral sermon and eulogized both Richard and Mary in the church filled with mourners. He particularly described Richard’s lifetime of piety and devotion to religion until he had his final stroke. After the service Richard and Mary Cranch were buried together in the Hancock Cemetery in Quincy.

[1] Richard Cranch was a largely forgotten historical figure until Robert D. Mussey, Jr. contacted the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors (NAWCC) and offered to donate his extensive research materials on Cranch in 2021. Mussey provided me access to his research collection, which allowed me to write the book titled Richard Cranch A Boston Colonial Watchmaker His Daybook and Horological Correspondence was published by NAWCC Publications in June 2025.

[2] Researches Among Funeral Sermons, Vital Records from New England Historical and Genealogical Register, New England Historical and Genealogical Society, 2014, AmericanAncestors.org; compiled from articles originally published in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register, vol. 7, p. 250.

[3] Suffolk County deeds, vol. 81.109, September 21, 1752.

[4] Richard Cranch to William Cranch, August 8, 1758, Cranch Family Papers, 1667-1946, box 1, folder 7, University of Wyoming, Laramie.

[5] Butterfield, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, Volume 1755-1770, pp. 143-144.

[6] Richard Cranch poem to Mary Smith, ca 1761, Cranch-Greenleaf Papers, 1749-1917, CU552, box 1, folder 1, Albany Institute of History & Art Library, Albany, NY.\

[7] Woody Holton, Abigail Adams A Life (Thorndike Press, 2010), 49-51.

[8] Ibid., 50-51.

[9] Ibid., 49.

[10] Mary Cranch Palmer to Mary Cranch, October 9, 1765, Historic New England, Boston, MA, (formerly Society for Preservation of New England Antiques), Cranch Family Letters. Item # 14.

[11] Mary Smith Cranch to Elizabeth “Betsy” Cranch, March 29, 1775, Caroline Chamberlain Family Papers, 1749-1954, Mss 618, Box 1, Wisconsin Historical Society.

[12] Nathaniel Cranch to James Elworthy, April 18, 1775, Nathaniel and Joseph Cranch Correspondence, folder 1, item no. 10, New England Historical and Genealogical Society, Boston, MA.

[13] Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates Volume XI, 1741-1745, 373.

[14] Lawrence J. Yerdan, “Richard Cranch: Churchman. Papers 1796-1799,” typescript December 1981, Richard Cranch Papers, Box 2, Quincy Historical Society.

[15] Brian Harkins, Esq., Senior Reference Attorney, Social Law Library, John Adam Courthouse.

[16] State of Massachusetts Bay, Province Laws – 1779-1780, Chapter 44, archives.lib.state.ma.us.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Province Laws – 1781, Chapter 6, archives.lib.state.ma.us.

[17] Commonwealth of Massachusetts Province Laws – 1781, Chapter 24, archives.lib.state.ma.us.

[18] Holton, Abigail Adams: A Life, 476-477.

[19] Ibid., 524-525.

[20] Mary Cranch to Abigail Adams, September 24, 1786, Adams Family Correspondence, Volume 7, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[21] Richard Cranch to John Adams, April 26, 1780, Adams Family Correspondence, Volume 3, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[22] Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, 372.

[23] Richard Cranch to John Cranch, June 20, 1783, William Cranch Papers: Cincinnati Historical Society, Cincinnati, Ohio, folder 37.

[24] Richard Cranch to James Elworthy, April 14, 1784, Cranch-Bond Papers, 1731-1938, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[25] Richard Cranch to John Adams, May 24, 1787, Adams Family Correspondence, Volume 8, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[26] The Independent Chronicle (Boston), March 18, 1788.

[27] Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, 374.

[28] John Adams to Abigail Adams, April 30, 1794, Adams Family Correspondence, Volume 10, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Recent Articles

Richard Cranch, Boston Colonial Watchmaker

Announcing the 2025 JAR Book of the Year Award!

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Recent Comments

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

I am not sure I will ever be convincingly swayed one way...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Interesting! Thanks, from a Charlotte NC Am Rev fan.

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

A great overview of that controversial document. I tend not to accept...