In 1775, the colony of Georgia faced heavy criticism for failing to support the American Revolution fully. The situation would change dramatically, as represented by a moment in 1776 connected to the famous events in Boston at that time, and also to East Florida, escaped enslaved people, Indigenous native peoples, and rice.

Georgia’s history had been the opposite of rebellion. In 1754, the colony was so weak that it was not included in Benjamin Franklin’s famous Albany Plan for the union of the rest of mainland America against the French colonies. In 1766, this province, alone among those that eventually rebelled, issued stamped paper, however briefly, during the Stamp Act Crisis.

With a small population, Georgia needed economic and military support from Great Britain. Hundreds of Georgians along the colony’s extremely long border with neighboring Indigenous tribes signed petitions in 1774 denouncing the Boston Tea Party and other acts of rebellion. Even the coastal merchants and planters from whom most of the rebels, such as they were, were drawn declined to send representatives to the First Continental Congress in 1775.[1]

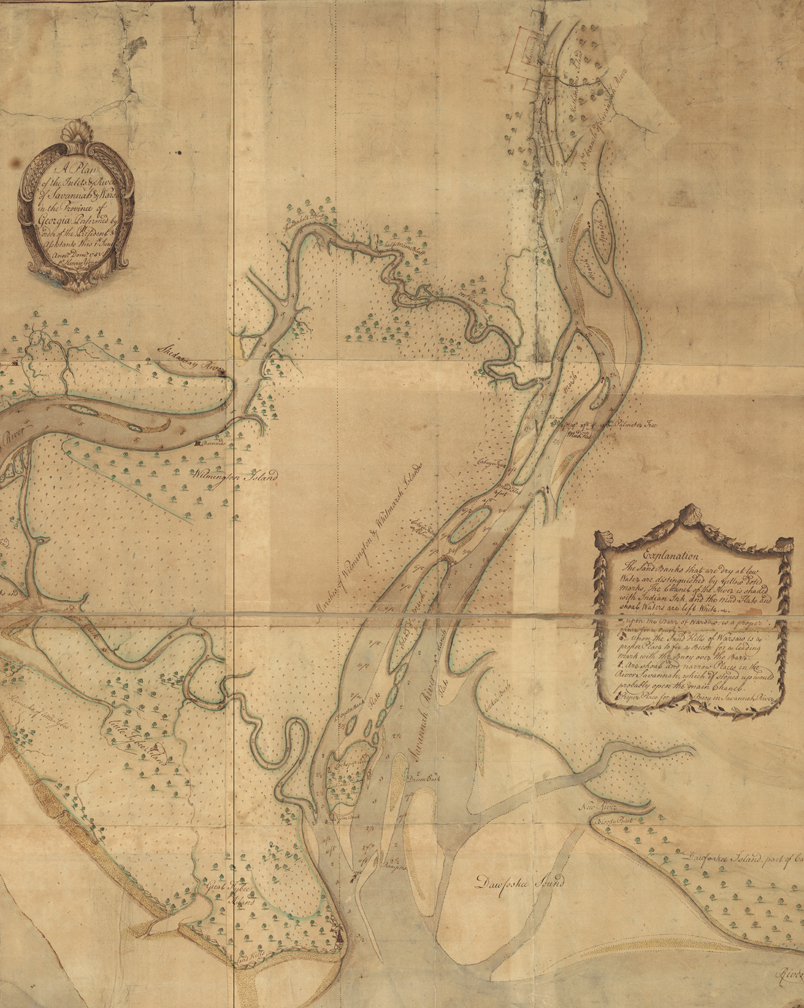

The dangers were real. Attacks by renegade Creek war parties had struck near Augusta in 1773-1774. Georgia was situated between British East Florida, powerful Indigenous Native nations influenced by the King’s agents, and thousands of men loyal to the Crown on the North and South Carolina frontier who wanted to remain in the British Empire. Two-fifths of the province’s population were enslaved, with the potential for an uprising. Whatever happened in Georgia also had consequences for neighboring South Carolina, which was much larger and wealthier.[2]

By January 1776, however, Georgia’s resistance had chosen the path to independence. They had thwarted every effort by the colony’s popular Gov. Sir James Wright to suppress the rebellion locally. The rebels took over the colony’s militia, arrested Wright and his council, adopted the Continental Association to restrict trade with Britain, and replaced the colonial assembly with a provincial congress. Georgia would have representation in the Second Continental Congress for the rest of the war, and its delegates would sign the Declaration of Independence.[3]

Supporters from Georgia and South Carolina reached out to the public, using persuasion, promotion, and persecution, even arguing that the British threatened slave uprisings. Events in Massachusetts influenced individual decisions, and not just in New England settlements. South Carolinian Barnard Elliott, for example, witnessed Col. John Thomas addressing his colonial militia in St. George Parish (later Burke County), Georgia, on July 6, 1775. He explained that he had, until that time, opposed the American measures. After learning of the violence at the battles of Concord and Lexington, however, he believed that “America was to be hard rode & drove like slaves.” He would now resign his two colonial commissions and join the Revolution.

South Carolinian Reverend William Tennant witnessed that Loyalist communities in Georgia organized to fight back for King and country, as they would to the end of the war. Even Thomas was later arrested for trying to join Loyalists from South Carolina attempting to reach British East Florida.[4]

Georgia’s commitment would be put to the test when, on January 13, 1776, a British fleet under Commodore Andrew Barkley arrived off Savannah to buy rice for the soldiers of the King’s army who were besieged in Boston. Deposed Royal Governor Wright escaped to Barkley’s fleet on February 11. Symbolic of how the times had changed, he was shot at by a guard from that same back country that had once supported him. What remained of the colonial governments of the four Southern colonies in revolt were now all refugees at sea.[5]

Wright sent a message to Georgia’s Revolutionary Council of Safety, urging them to sell the rice to Barkley, for the British fleet had the military power to take what it came for and could exact retaliation on Savannah. (In reality Barkley only had 390 sailors and marines and 200 soldiers, too small a force to mount any significant military action.)

The commodore tried to negotiate a purchase of 3,000 barrels of rice. Technically, the Continental Association excluded rice from its non-exportation policy. Barkley also knew that when the Continental Association expired on March 1, the Georgians could trade with Britain.[6]

The month before, South Carolina’s rebels had agreed to sell to the British in exchange for Barkley not seizing the ships. That agreement fell through because the commodore had taken enslaved people aboard with an offer of freedom, like the action taken by Virginia’s Royal Governor John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, the previous November 5.[7]

At the last moment the Georgia Council of Safety, under its president, George Walton, chose to refuse to sell to the British under any circumstances. On March 1, they ordered that Savannah be defended and, if necessary, destroyed to prevent the enemy from seizing ships full of rice (“riceboats,” as written at the time). They issued orders to disable the vessels.

Georgia’s rebels were ill-prepared to defend Savannah. Their mixed defense force consisted of the first twenty to thirty enlistees in Georgia’s new Continental Battalion under Col. Lachlan McIntosh, 300 to 400 militiamen under Col. Samuel Elbert, and 153 South Carolina militia under Maj. John Bourguin. These soldiers were spread out to defend Savannah rather than to guard the rice boats.

On March 2, 1776, Barkley responded. He used his smaller vessels to land 300 marines, sailors, and soldiers under Marine Capt. John Maitland on uninhabited Hutchinson Island on the northeast side of Savannah harbor. The rice boats, with their seamen, were gathered there. On March 3, the men assigned to make those merchant ships immobile were captured by the British when they arrived at the vessels.

Upon learning of the seizure, the rebels set a vessel on fire (a “fire ship”) and sent it drifting towards the rice boats, hoping to engulf them in flames. That ship proved too large and went aground. When a second fire ship succeeded in igniting a couple of ships, the British withdrew from Hutchinson’s Island as Americans under McIntosh fired cannon and small arms upon them. At least four other ships were deliberately burned in the conflict, and the fire spread to other vessels.

Barkley collected his men and ten rice boats. The sailors struggled to avoid having the heavily laden vessels run aground in getting out of the shallow harbor, even to the extent of having to lighten the load by throwing rice overboard. The fleet filled two merchant ships with 1,600 barrels of rice.

The commodore withdrew his fleet to Big Tybee Island, where parties of his sailors, soldiers, and civilians could go to the plantations on shore. On March 7, before Barclay could take any action against Savannah, if any were ever intended, some 400 South Carolinians under Col. Stephen Bull arrived to reinforce McIntosh.[8]

Creek warriors also participated in the defense of Savannah. Their confederation had just ended a British-arranged war with the Choctaws and Chickasaws, and before that, with the Cherokees. This peace party was in Savannah to meet with their friend, the trader Jonathan Bryan, about the American Revolution. He urged them to be neutral, as did the King’s agents among them, initially. While at Bryan’s house, the Creeks were mistakenly fired upon by Barkley’s men. They sent for help, and reportedly 500 warriors came to Savannah’s defense. For the rest of the war, the Creeks would be divided in a civil war between supporting the British and remaining neutral. They never again fought on the side of the patriots.[9]

In 1775, some 200 to 300 escaped African Americans were on Big Tybee Island, under the protection of Barkley’s ships and marines. On March 25, a rebel party commanded by Archibald Bulloch, with white and Creek members all dressed as native warriors, made a raid on the island in an unsuccessful attempt to capture Governor Wright. All houses, except one where a sick woman and several children lived, were burned. Contrary to legend, no African Americans were injured, and there was no massacre of these people for attempting to escape from slavery.

Modern speculation has it that these formerly enslaved were taken away by the British and sold back into bondage, but this was not the case. They were, instead, set free in new lands. Wright, who had been Georgia’s largest owner of slaves, argued that this action set a bad precedent.[10] By the end of the revolution, thousands of African Americans had fled to British lines.

The casualties on both sides in the battle for the rice boats were light. Bullock’s party claimed to have killed two British Marines and one Loyalist American. The latter was scalped. Barkley wrote that he suffered six men wounded. The Whigs had two white men killed and one Creek warrior wounded. Barkley finally agreed to an exchange of his prisoners for members of Wright’s administration and council before setting sail for Boston.

The British fleet finally left on March 31, taking with them Wright, his colonial council, and other colonial officials. Scottish merchants in Savannah followed soon after as the Council of Safety ordered the prosecution of people remaining who were perceived to be enemies of the state.[11]

Denying the sale of foodstuffs to Great Britain and its possessions had consequences. Across the Empire’s Caribbean possessions enslaved people starved, and hundreds died, because of the cutoff of trade in provisions from Georgia and South Carolina. Smuggling continued from Georgia until the British invasion in late 1778. The King’s army invaded those two provinces from 1778 to 1780, in part, in a failed effort to restore the food supply for the enslaved labor of their all-important sugar islands.[12]

After Georgia’s new rebel government refused to sell foodstuffs to the British, Royal Governor Patrick Tonyn of the neighboring loyal colony of East Florida was compelled to order cattle raids into Georgia. Thousands of Loyal Americans and their enslaved workers fled to St Augustine, far more people than the colony could feed.

The American Revolution expanded to include this Southern front. Loyalist bands of raiders reached across Georgia to Augusta, seizing horses and enslaved people for sale. They committed violent crimes—retaliatory raids by the new state of Georgia and three unsuccessful invasions of British East Florida followed.[13]

The rebels exaggerated the importance of this “victory” in the Battle of the Riceboats at Savannah. Through bad decisions and ignorance of the real situation, they had allowed Barkley to escape with the rice ships. The British captain lacked the resources or, likely, the desire to threaten Savannah.[14]

Georgia, despite political, economic, and military problems, had finally firmly and fully committed to the American cause, the last colony to do so. The Council of Safety would make up for the rice that went with Barkley by supplying the American forces in Boston with gunpowder seized from British merchant ships.[15] Georgia sent delegates to the Second Continental Congress who signed the Declaration of Independence.

The province joined the American Revolution at a price. In 1777, Georgians defeated South Carolina’s proposal for a union between the two provinces. No state was so thoroughly devastated by the war in the years that followed. Killing in the civil war that engulfed the Revolutionary War South became so common that a cynical joke called the murder of prisoners of war “granting a Georgia parole.”[16]

Even at the end of the war, British leaders falsely believed that the Empire could retain Georgia and South Carolina as colonies to profit from Britain’s slave trade, to feed the enslaved in its highly profitable sugar colonies, to close off the Caribbean to America, and to secure a stake in the future of the southern region of North America.[17] The united thirteen states and their Continental Congress would not allow that to happen.

Britain did conquer Georgia in 1778-1779 and made it the only state restored to colony status. That expensive effort was a failure due to the war’s cost across the South, France’s and Spain’s intervention, and the defeat at Yorktown, Virginia. The King’s forces finally evacuated from the South in 1782.[18]

Britain should have learned from the Empire’s defeats in Cuba and the Philippines that an expeditionary force of 30,000 men, prone to desertions and disease, could only defeat nations, not subdue the three million American people.[19] Americans had no colonies to lose; bankruptcy and the defeat of armies did not matter, as even British leaders repeatedly pointed out.

The British failure began in 1775 and 1776 in many places in America, including in Georgia, with the events that came to be called the Battle of the Riceboats. America’s states fought for the independence of all, the beginning of a new nation of one.

[1] Greg Brooking, From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2024), 60-78, 122-123, 157-158; Robert S. Davis, comp., Georgia Citizens and Soldiers of the American Revolution (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1979), 11-19.

[2] James Michael Johnson, Militiamen, Rangers, and Redcoats: The Military in Georgia, 1754-1776 (2nd ed., Wast Point, NY: West Point Press, 2024), 91-94.

[3] Kenneth Coleman, The American Revolution in Georgia (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1958), 39-54.

[4] Joseph W. Barnwell, “Barnard Elliott’s Recruiting Journal,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 17 (July 1916): 97; William Tennent diary, September 7, 1775, in R. W. Gibbes, comp., Documentary History of the American Revolution, 3 vols. (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1853-1857), 1:235; Robert S. Davis, “Civil War in the Midst of Revolution: Community Divisions and the Battle of Briar Creek, 1779,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 100 (Summer, 2016): 136-159. Thomas would remain a Loyalist and was wounded in the Battle of Burke County Jail in 1779. He was allowed to return to Georgia after the war. Robert S. Davis, Georgians in the Revolution (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1986), 104, 107

[5] Rick Atkinson, The British are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777 (New York: Holt, 2019), 34.

[6] Harvey H. Jackson, “The Battle of the Riceboats: Georgia Joins the American Revolution,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 58 (Summer, 1974): 230-236; Jim Piecuch, Three Peoples, One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South, 1775-1782 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2008), 82.

[7] Jim Piecuch, “Preventing Slave Insurrection in South Carolina & Georgia, 1775-1776,” Journal of the American Revolution, February 21, 2017, allthingsliberty.com/2017/02/preventing-slave-insurrection-south-carolina-georgia-1775-1776.

[8] Johnson, Militiamen, Rangers, and Redcoats, 139-159; Robert S. Davis, “The Battle of the Riceboats: British Views of Georgia’s First Battle of the American Revolution,” Proceedings and Papers of the Georgia Association of Historians 1981 (1982): 111-122; Gordon B. Smith, Morningstars of Liberty: The Revolutionary War in Georgia, 1775-1783, 2 vols. (Milledgeville, GA: Boyd Publishing, 2006, 2011), 1:55-57. Bryan had been trying to persuade the Creeks to allow him to establish his own colony in Florida. See Alan Gallay, Jonathan Bryan and the Southern Colonial Frontier: The Formation of a Planter Elite (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989).

[9] Robert S. Davis, “George Galphin and the Creek Congress of 1777,” Proceedings and Papers of the Georgia Association of Historians 3 (1982): 13-29, and “The Battle of the Riceboats,” 111-112.

[10] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:56-57; Piecuch, Three Peoples, One King, 84-85; Memorial of Sir James Wright to Lord George Germain, January 6, 1779, in Allen D. Candler, comp., “The Colonial Records of the state of Georgia,” 39 volumes (unpublished transcripts, 1941), 38, pt. ii, 138. For many of the documents associated with the “Battle of the Riceboats” see volume five of Mary Bondurant Warren and Jack Moreland Jones, comps. Georgia Governor and Council Journals, 9 vols. (Athens, GA: Heritage Papers, 1991-2005).

[11] Johnson, Militiamen, Rangers, and Redcoats, 159; Brooking, From Empire to Revolution, 156.

[12] Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, An Empire Divided: The American Revolution and the British Caribbean (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 161-162, 244, 252, n13; Coleman, The American Revolution in Georgia, 169.

[13] See Martha Condray Searcy, The Georgia-Florida Contest in the American Revolution, 1776-1778 (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1985).

[14] Johnson, Militiamen, Rangers, and Redcoats,160.

[15] Robert S. Davis, “A Georgian and a New Country: Ebenezer Platt’s Imprisonment in Newgate for Treason in ‘The Year of the Hangman,’ 1777,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 84 (2000): 106-115.

[16] Coleman, The American Revolution in Georgia, 89; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, So Far as It Related to the States of North and South Carolina and Georgia, 2 vols. (New York: D. Longworth, 1802), 2:336; E. W. Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Characters Chiefly of the Old North State (Philadelphia, PA, 1854), 431; Dr. Thomas Taylor to Rev. John Wesley, February 28, 1782, Shelbourne Papers, William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan; “SAVANNAH, MARCH 14,” Royal Georgia Gazette (Savannah), March 14, 1782.

[17] Coleman, The American Revolution in Georgia, 89.

[18] Brooking, From Empire to Revolution, 157-158, 175-203; Robert S. Davis, “The British Southern Strategy in the American Revolution, 1775-1782,” British Journal for Military History 11 (August 2025): 2-24.

[19] For British failure in Cuba, see Elena A. Schneider, The Occupation of Havana: War, Trade, and Slavery in the Atlantic World (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), and for the Philippines, see Shirley Fish, When Britain Ruled the Philippines, 1762-1764: The Story of the 18th Century British Invasion of the Philippines during the Seven Years War (n. p.: S. Fish, 2003).

One thought on “The American Revolution Comes to Georgia: The Battle of the Riceboats, 1776”

Excellent article. Thank you for correcting the narratives I had learned.