The year is 1764, and smallpox is sweeping the town of Boston. One of Paul Revere’s children is stricken, and the family chooses to quarantine in their home until the child recovers.[1] The local newspapers document new smallpox cases. Incoming vessels with smallpox victims on board are impounded, and the passengers and crews are immediately quarantined. The newspapers run advertisements urging citizens to get inoculated against smallpox, as advocated by Dr. Joseph Warren, a prominent Boston physician in the town and early proponent of public health measures to contain the disease. As a precaution, residents of neighboring towns are sternly warned not to enter Boston seeking inoculation, or risk prosecution. Even deadlines for submitting tax abatement requests are extended for people unable to register because of the quarantine restrictions.

Within one year, smallpox is reduced to a sidebar,[2] and the newspapers of Boston are filled with diatribes against the new Stamp Act passed by a Parliament in London. The Boston town meetings have metamorphosed into a growth medium for political discontent, and are now featured prominently in the newspapers. In 1764, The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser, one of four local newspapers, published the proceedings of Boston town meetings as small inserts on inside pages. By 1765-6, the town meeting reports occupied up to two columns of print, sometimes appearing even on the first page. What happened to provoke such a dramatic change?

The answer is reflected in a previously unpublished invoice issued by the printing firm Green and Russell, publishers of The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser, to the town of Boston for printing and publishing services.[3] The title of the invoice reads, “The Town of Boston to Green & Russell, Dr”[4] (Figure 1A). The document records a number of transactions from 1765 to 1768, during which the town placed a series of advertisements and notices in the firm’s newspaper. Each entry lists the date, subject, and cost of the transaction.[5] On the reverse side is written, “Green & Russell Recd. £20.6.4 July 1768 (allowed)” (Figure 1B).

The time period covered by the document was an extraordinary one in American colonial history, nowhere more so than in Boston. A single event in 1765 served to unite disparate political factions and provoke outspoken criticism of Britain, and even riotous demonstrations against its established authority. The event was the passage of the Stamp Act by the British Parliament on March 22 of that year.

Newspaper printers felt particularly threatened by the Stamp Act, as it levied substantial taxes not only on the paper on which the journals were printed – paper that had to be imported because of the lack of a developed domestic paper industry – but also directly on many of the advertisements placed in the newspapers. A summary of the terms of the Stamp Act was printed in The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser on April 6, 1765.[6]

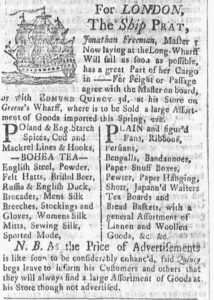

To appreciate the impact of the impending Stamp Act taxes on newspaper revenues, consider this advertisement for dry goods and other imports placed on June 10, 1765 by “Edmund Quincy 3d, at his Store on Greene’s Wharff” (Figure 2). The bottom of the lengthy advertisement states: “N.B. As the Price of Advertisements is like soon to be considerably enhanc’d, said Quincy begs leave to inform his Customers and others that they will always find a large Assortment of Goods at his Store though not advertised” (italics added). Little wonder that the printers felt threatened by the impending taxes! Yet, protestations to Parliament predicting economic ruin of the colonial press were to no avail, including those in London by Benjamin Franklin, who had risen to prominence as a Philadelphia printer.[7]

Public demonstrations against the Stamp Act taxes led to mob riots in Boston in August 1765, which included the ransacking and devastation of the homes of the designated collector of the Stamp Tax, Andrew Oliver, and the Massachusetts lieutenant governor, Thomas Hutchinson. In the face of this widespread criticism and sometimes violent acts, the Stamp Act was repealed by Parliament after one year in March 1766. But it was soon replaced by the equally unpopular Townshend Acts of 1767-68 that authorized a series of importation taxes, affecting numerous widely-used and essential household goods.

The Firm of Green & Russell

In Boston, the printing company Green and Russell (John Green, 1731-1787, and Joseph Russell, 1734-1795) had been publishing newspapers since its formation in 1755. The name of the paper changed several times over the years, but in 1765 it was known as the Boston Post Boy and Advertiser, appearing once weekly on Mondays, and available either at their establishment on Queen Street or by delivery to subscribers.

Advertisements were interspersed throughout the four pages of that paper and were a substantial source of revenue for the publishers.[8] Besides the usual commercial advertisements for pickled salmon, kippers, Tilloch’s snuff, wet nurses, and choice Cadiz salt, there were official “advertisements” and notices (or “inserts”) placed in the newspaper. The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser was designated the official organ of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and of the customs commissioners, printing their deliberations and notices on a regular basis. Likewise, the town of Boston, specifically its governing Board of Selectmen, placed advertisements and notices.[9] The Green and Russell invoice enumerates the publishing costs for a number of these items.

Invoice Description and Verification

There are twenty legible entries in the invoice, from October 28, 1765 to March 28, 1768[10] (Table 1, at the end of this article). Each entry in the invoice is described in one of three ways: “To adv.” or “To advertising” (nine entries); “To inserting” (ten entries); and, “To Paper & Printing of Notifications for calling Town Meetings” (two entries).[11] The twentieth entry had both an advertisement and an insert.

To verify the accuracy of the invoice, each item that related to advertisements or inserts was compared to the printed newspaper, on or around the date of the invoice entry.[12] All were corroborated as having been published in the newspaper either on, or within a couple of weeks of, the date of the invoice entry[13] (Table 1, column 3).

The subjects of the advertisements and inserts varied considerably. Some regarded domestic issues such as taxation (three items), the enforcement of Town regulations (five), and the rental of Town property (two). Others reported resolutions from the Town Meetings (eight), which during this time period were of a decidedly political nature. The published invoice items were all either ordered by the Boston Board of Selectmen, or, in the case of the town meetings, attested to by William Cooper, the town clerk.

Those items apparently emanating directly from the selectmen (indicated as such in the published version) were cross-checked for correspondence against the published Minutes of the Selectmen’s Meetings. In almost all cases, reference to the advertisement or insert could be found in the Minutes, on or around the date of the invoice entry[14] (Table 1, column 4).

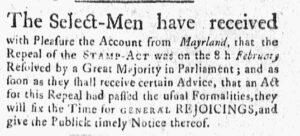

One example of the concurrence between an invoice item, its authorization in the Minutes of the Selectmen’s Meetings, and the published advertisement in The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser, calls for the people to celebrate the Repeal of the Stamp Act. The Minutes for the Selectmen’s Meeting for April 14, 1766 include: “A letter from the Sons of Liberty relative to the repast of the Stamp Act was read. Whereupon Voted that the following Advertizement be sent to all of the Printers – The Selectmen.”[15] The corresponding entry in the Green and Russell invoice for April 14 states, “To Adv. The Selectmen will fix a Day for general Rejoicing Repeal Stamp Act.” The published advertisement in the Boston Post Boy and Advertiser for April 14 is shown in Figure 3.

An identical advertisement was placed in Edes and Gill’s Boston Gazette on that day, as well as in the Drapers’ Massachusetts Gazette three days later (that paper’s usual publication day). The Selectmen, eager to reach the widest audience to spread the word of such a victorious event, were willing to pay for advertisements in several newspaper publications.

The four newspaper-publishing firms, despite representing a wide spectrum of political opinion, banded together, and at their own expense jointly issued a broadside calling for a celebration of the “Glorious News” (Figure 4). The broadside was printed and distributed free to the public at the publishers’ respective offices.

The actual day for celebration was delayed until May 19, 1766, so that the signing of the Repeal Bill by the King could be verified, at which time the Selectmen determined, “Mr. Williston was ordered to notify all the Sextons in Town to begin ringing their several Bells at five a Clock in the Morning to continue till six a Clock in the Evening.”[16] “Music sounded throughout the town … Swelled by strolling musicians, the streets were soon impassable … Bonfires dotted the town that evening … Boston appeared ablaze.”[17]

Those advertisements relating to the Selectmen’s regulatory role in the town included some that shock our sensibilities today, but that, in fact, reflected the inequitable structure of Boston society in the 1760s. One of these (#1) exhorted the residents to “Keep their Negroes in after 9 O’clock,” and another (#11) warned that the watchmen of the town would apprehend “Negro, Indian or Mulatto slaves” out after nine o’clock without “Lantorns with light Candles.”

In keeping with the Selectmen’s public health function, the nineteenth entry read, “To inserting the Carcases of several Horses left unburied.” The corresponding Selectmen’s Minutes for that time explained the Board’s thinking on the matter:

Whereas the Carcases of several Horses which have died of a Contagious disorder now prevalent, have been carried into the Common & other Parts of the Town & left unburied, whereby some ill consequence are apprehended. These are therefore to acquaint the Inhabitants, that such Persons as may hereafter leave the dead Bodys [sic] of Horses or any other Creatures so exposed above Ground, will be prosecuted for such offences according to Law.[18]

The advertisement in the newspaper was virtually identical to the copy in the Selectmen’s Minutes, except that someone, perhaps the paper, had corrected the spelling of ”Bodys” to “Bodies.”

Charges for Advertisements, Inserts, and Printing Circulars

The cost for each advertisement, insert, or printing of circulars is clearly noted on the invoice. Other than this one invoice, information on the cost of advertisements in colonial newspapers during this time period has been limited to instances in which the papers themselves listed their advertising prices.[19] In general, newspapers indicated merely that advertisements could be placed at the printer’s office, sometimes adding, “at a reasonable cost.” We could find no other published example of an invoice or other document showing actual costs.

The cost for each advertisement or insert, as one would expect, increased with the amount of space it occupied in the newspaper. Column 11 in Table 1 shows the cost per newspaper column length, as computed from the pricing on the invoice, and the length of the ads as they appeared in the newspaper.[20]

The minor ads (for taxes, public safety, and real estate) occupied less than one-quarter of a column, with a median base cost of four shillings. The longer advertisements and inserts, mostly town meeting reports, occupied from almost half a column up to two columns. The median cost per column length for the longer advertisements was about £1:8:7 (expressed as a decimal, 28.6 shillings), with minor variation, except for one outlier (#5). By contrast, the variation in cost per column length among the shorter items was considerable. This suggests that there was a minimum base price for shorter advertisements, and a higher price for longer ones, based on the length of the advertisement.[21]

Most of the advertisements and inserts appeared on pages 2 or 3 of a 4-page publication, or pages 4 or 5 of a 6-page supplement. However, one of them (#18), a notice from the town meeting of December 20, 1767, which gave instructions to the town’s representatives in the general court to request repeal of the Townshend commodity taxes and to encourage native industry, occupied two full columns on the front page of the newspaper. The cost per column length of this insert was 29.1 shillings, only slightly higher than the median value of 28.6 shillings. The other page 1 insert (#17) cost even less than the median value. Thus, there appeared to be no significant surcharge for the placement of the published items on a page 1 location.

The most eye-catching item (#16) was an appeal to the townspeople to sign the subscription pledging to “promote Industry, Oeconomy, and Manufactures: thereby to promote unnecessary Importation of Europe Commodities which threaten the country” (in essence, a non-importation agreement). It was the only published item with a “banner” title that extended across the page above all 3 columns: “Save your MONEY, and you Save your COUNTRY” (Figure 5). Significantly, The Selectmen’s Minutes from the same date as the newspaper publication contained the following instruction: “Mr. Sewall appointed to give directions relative to the printing, the Vote of the Town relative to Inumerated Goods.”[22] It was unusual for the Board of Selectmen to designate in the minutes that one of its members should provide printing instructions for a town meeting insert in the newspapers. This clearly shows that the Selectmen considered this item to be deserving of special attention, and reveals that they intended to use the banner advertisement to influence public opinion – that is, it must be “writ large.”

Among the most costly items in the invoice were the printing of circulars to announce town meetings (#4 and #10), priced at £2:4:0 for 2,000 circulars.[23] The population of the town in the 1765 census included 2,069 families in 1,676 dwellings; the 2,000 circulars were more than enough for one circular per household.[24] Some of the circulars would have been posted or distributed in public places, while many were either picked up by subscribers at the printers’ offices or delivered by the newsboys, or “carriers,” directly to subscribers’ homes.

Advertising A Revolution

By 1765, the town meetings had come to dominate much of public discourse, and, consequently, to occupy considerable newspaper space. The records of town meetings, usually listed as “inserts” in the invoice, read like a compendium of significant events of the day – grievances and perceived injustices that provoked public outcry and, in some cases, led to brutal riots: denial of due process in the courts (#2,#3); customs officers’ depositions kept secret from the populace (#9); and nonimportation agreements and entreaties for repeal of commodity taxes (#16, #17, #18, #20). The publication and dissemination in the newspapers of the proceedings of the town meetings not only recorded their deliberations and resolutions, but also, more than likely, contributed to the ensuing public outcry and violence against Parliament and the crown’s representatives.[25] In both a real and a figurative sense, a number of the published items listed in the original invoice represent the advertisement of a revolution, a drum roll leading to the uprising of 1774 that led to war in 1775.

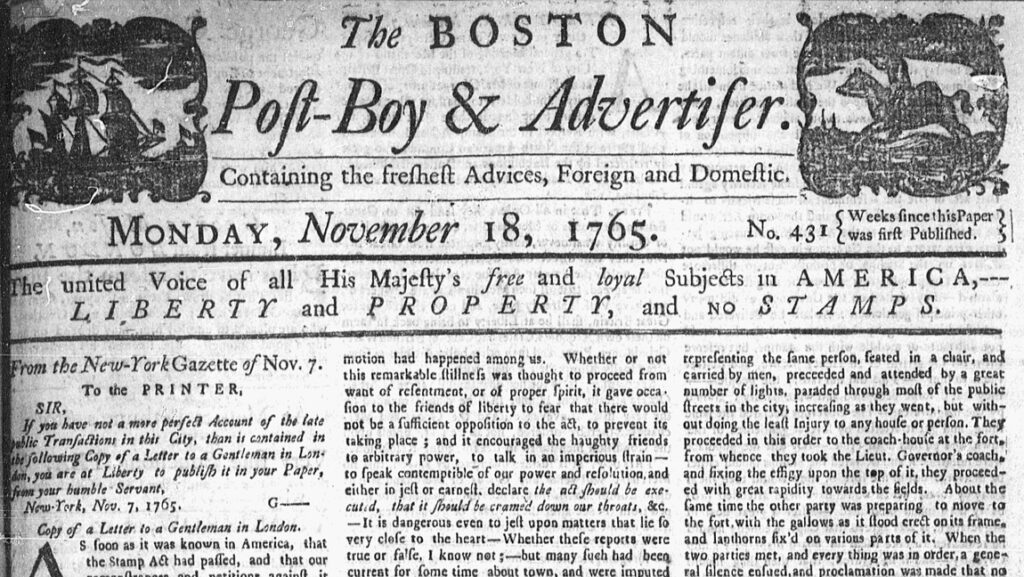

After the passage of the Stamp Act, newspapers in Boston continued to print articles, advertisements, and notices as they had before the Act, but now the printers became overtly militant against the Stamp Act, and opposed other “external” Parliamentary taxes as well. While Green and Russell continued to publish the proceedings of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and other official notices in The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser or in broadsides and pamphlets, now under the newspaper’s masthead, they prominently and defiantly displayed: “The united Voice of all His Majesty’s free and loyal Subjects in AMERICA, — LIBERTY and PROPERTY, and NO STAMPS” (figure 6).

Even in verse, Green and Russell expressed their dim views of the Stamp Act taxes in two of their end-of-year broadsides: December 31, 1765, nine months after the passage of the Stamp Act, and December 31, 1766, nine months after the repeal of the Stamp Act.[26] (The broadsides were printed annually to solicit New Year’s donations for the newsboys, who distributed them to their list of subscribers.) The 1765 broadside read, in part:

Ah! The Times sure are hard,

But we’ll pay no regard

To the Stamps, Mobs, Devils or Popes;

The freedom of Press

Will gain the Success,

And fully Accomplish our Hopes

The 1766 broadside included:

Kind Sirs, I greet you, in a Joviall Strain;

And feel the blood flow quick thro’ ev’ry Vein.

Joy to New England, is the cry;

The STAMPS are dead,

And we are freed

While rejecting the Stamps, the printers Green and Russell also rejected mob rule, and compared the taxes with the bugaboos of the devils and (Heaven forbid) the Popes. In these public poems, they castigated the taxes not as a threat to business, but as a threat to liberty!

The advertisements and inserts appearing in the Green and Russell invoice, and the political positions behind them, were initiated not by the newspaper, but by the increasingly radical leadership in the town. The seven members of the Boston Board of Selectmen included John Hancock and John Rowe, and those who controlled the town meetings, Samuel Adams and James Otis prominent among them. Whether for pecuniary or ideological reasons, or a combination of both, the printers of the four newspapers formed alliances with the town’s activist leaders to disseminate their mutual grievances; the most efficient way to accomplish this was by the town purchasing print space in local newspapers.

A case in point is the Selectmen’s inserting a “Letter of thanks to Author of Farmers Letters” (#20, at a cost of eighteen shillings), a widely disseminated series of letters first published in Philadelphia anonymously by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania.[27] At the Boston town meeting on March 28, 1768, “the following Letter was reported by the Committee appointed for that Purpose, viz. To the ingenious AUTHOR of certain patriotic Letters subscribed a FARMER.” What ensued was a panegyric to Dickinson for his “Wisdom, Fortitude and Patriotism” in opposing the unfair taxes of the Townshend Acts, ending with the instructions: “The above letter was read, and unanimously accepted by the Town, and ordered to be published in the several News-Papers.” The letter of thanks appeared on that same day in The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser, and was also published in the three other newspapers.[28]

This collaboration between the press and the town was enabled, in a sense, by a “perfect storm:” On the one hand, the Stamp Act had united printers of disparate political ideologies, and, at the same time, it had allied the populace (as represented in the Town Meetings, through their elected Selectmen, and with extra-governmental groups such as the Sons of Liberty) to the press.[29] Together, intentionally or not, they were advertising what would soon become a revolution. The Green and Russell invoice substantiates this alliance, and places a monetary value on it. From a present-day perspective, the cost to the town seems a bargain.

| # | Date on Invoice | Date Published | Date Selectmen’s Meeting | Subject (abbreviated) | Ad (A)

Insert (I) Print (P) |

page # | Length Ad-Insert, mm. | Decimal fraction of a news column length

|

Cost: Ad- Insert, shillings* | Cost: shillings/

column length (smaller items in parentheses) |

| 1 | 10/28/65 | 11/04/65 | Not Found | Negroes 9 o’clock | A | 3 | 2.5 | .09 | 4 | (44.4) |

| 2 | 12/23/65 | 12/23/65 | Town Mtg.: Memorial Courts | I | 3 | 17 | .64 | 15 | 23.4 | |

| 3 | 12/30/65 | 12/30/65 | Town Mtg.: Open Courts | I | 5/6 Suppl | 12 | .45 | 12 | 26.7

|

|

| 4 | 3/6/66 | —- | 3/5/66 | Printing Circulars | P | 44 | N//A | |||

| 5 | 3/31/66 | 3/31/66 | Town Mtg.: Answer Address from Plimouth | I | 2-3 | 19.5 | .73 | 12 | 16.4

|

|

| 6 | 4/7/66 | 4/7/66 | 4/16/66 | Deer Island to Let | A | 2 | 3 | .11 | 4 | (36.4) |

| 7 | 4/14/66 | 4/14/66 | 4/14/66 | Repeal Stamp Act… Rejoice | A | 3 | 2.5 | .09 | 4 | (44.4) |

| 8 | 8/25/66 | 8/25/66 | Not Found | Assessors’ Lists | A | 2 | 4 | .15 | 5 | (33.3) |

| 9 | 10/13/66 | 10/13/66 | Town Mtg.: Customs Deposition; Losses from Riots | I | 2 | 38 | 1.42 | 40 | 28.22

|

|

| 10 | 11/26/66 | —- | 11/24/66 | Printing Circulars | P | N/A | N/A | N/A | 44 | N/A |

| 11 | 12/22/66 | 12/22/66 | Not Found | Apprehend Negroes | A | 3 | 3 | .11 | 4 | (36.4) |

| 12 | 3/09/67 | 3/23/67 | 3/10/67 | Land on Neck | A | 2 | 1.5 | .06 | 3:4 | (56.7) |

| 13 | 7/27/67 | 7/27/67 | 7/22/67 | Gaming | I | 3 | 6 | .22 | 6 | (27.3) |

| 14 | 8/24/67 | 8/24/67 | Not Found | Assessors | A | 3 | 4.5 | .17 | 5:4 | (31.8) |

| 15 | Illegible | 9/14/67 | 9/9/67 | Town Ladder | A | 3 | 3.7 | .14 | 5:4 | (37.1) |

| 16 | 11/2/67 | 11/2/67 | Town Mtg.: Manufacture (Save your MONEY AND COUNTRY) | I | 4/6 Suppl. | 41.5 | 1.55 | 48 | 31.0 | |

| 17 | 11/30/67 | 11/30/67 | Subscription Rolls (non-importation) | I | 1 | 13.5 | .51 | 13:4 | 26.3

|

|

| 18 | 12/28/67 | 12/28/67 | Town Mtg.: Repeal Commodity Taxes & Manufacturing Constraints | I | 1 | 44 | 1.65 | 48 | 29.1

|

|

| 19 | 2/15/68 | 2/15/68 | 2/10/68 | Carcases of Horses | I | 2 | 3.5 | .13 | 4 | (30.8) |

| 20 | 3/28/68 | 3/28/68 | A.: Town Mtg.: Farmer Letters | I | 3 | 17 | .63 | 18 | 28.6

|

|

| B. Town Mtg.; Tax Abatement | A | 3 | 4 | .15 | 5 | (33.3) |

Table 1. Dimensions and costs of each advertisement or insertion, with calculated cost per newspaper column length. *Original invoice shows costs in pounds:shillings:pence; here converted to shillings, at 20 shillings/pound, and 12 pence per shilling for ease of calculations.

[1] The Boston Board of Selectmen wanted to send the child to a “pesthouse” for quarantine, but the family refused, and chose instead to sequester the entire family at home. A Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston, Containing the Selectmen’s Minutes From 1764 Through 1768 (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, City Printers, 1889), 31-32 (February 6, 1764).

[2] The epidemic peaked in the winter of 1764, and was probably on the wane by mid-1765, thanks, in part, to Warren’s and others’ inoculation campaign. Christian di Spigna, Founding Martyr: The Life and Death of Dr. Joseph Warren, The America Revolution’s Lost Hero (United States: Crown, 2019), 61-64.

[3] This document is in the possession of the author. It has a watermark consistent with paper of an eighteenth-century European origin: a heraldic crowned lion grasping a sheaf of arrows on one side and a pole topped by a hat on the other. The border is inscribed “PRO PATRIA EIUSQUE LIBERTATE,” and the Dutch word “VRYYHEYT” appears in the center below the lion.

[4] “Dr” refers to debit (i.e., the town is indebted to the firm).

[5] Two of the entries were “To Paper and Printing 2000 Notifications for calling Town Meeting.” The rest were either identified as “to advertising” or “to inserting [a notice].”

[6] Boston Post Boy and Advertiser, April 8, 1765: “Last Wednesday Evening arrived here the Ship London Packet … by whom we have the following Extraordinary Intelligence. viz … The Honorable House of Commons on the 7th of February passed 55 Resolves, which we hear are since passed into an ACT OF PARLIAMENT – The Resolves are for imposing certain STAMP DUTIES in America … For every NEWS-PAPER, or pamphlet, containing half a sheet, One-half penny. For every whole sheet, ditto, one penny. For every advertisement, Two shillings.” Additionally, virtually every legal and commercial document required a stamp.

[7] Franklin, living in London and representing the interests of Pennsylvania in the halls of power, argued strenuously against the passage of the Stamp Act. When it became law, however, he urged his printing partner in Philadelphia, David Hall, to comply with the tax. After Hall publicly announced this decision, he faced considerable backlash from fellow printers as well as subscribers to his newspaper – which Franklin had founded decades before – the Pennsylvania Gazette. Hall was castigated by fellow printers for not reprinting widely publicized, critical newspaper articles from other parts of the Colonies that railed against the Act, while, in protest, 500 subscribers to the Gazette reportedly cancelled their subscriptions in the two weeks preceding the law’s taking effect. Hall stopped printing the newspaper the day before the tax would have been required and later, like some other printers, tried to get around the tax by publishing the newspaper without an identifying masthead. Ralph Frasca, “Benjamin Franklin’s Printing Network and the Stamp Act,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 71, no. 4 (2004): 408-410.

[8] Joseph M. Adelman, Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News, 1763-1789 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019), 33.

[9] The Town placed advertisements and notices in other Boston newspapers as well, often duplicates of those in The Boston Post Boy. There were four active newspapers in Boston during this time. Three were Loyalist-leaning: The Boston Chronicle (John Mein and John Fleeming); The Boston Newsletter (Richard Draper and Samuel Draper); and, The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser (John Green and Joseph Russel). The fourth was decidedly Patriot: The Boston Gazette and Country Journal (Benjamin Edes and John Gill). Timothy M. Barnes, “Loyalist Newspapers of the American Revolution 1763-1783: Bibliography,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 83, Part 2 (1973): 218-222.

[10] At least one additional entry at the bottom of the document is partly cut off, and is not legible.

[11] The distinction between an “ad” and an “insert” is not always clear. With a few exceptions, the town meeting notices were listed as “to inserting,” while the shorter items for public safety issues, real estate, and taxes were written as “to advertising” or “to adv.”

[12] All of the Boston Post Boy and Advertiser newspaper numbers for the time period covered by the invoice were reviewed on Readex (readex.com)

[13] The date of entry in the invoice of item #15 (regarding the town ladder) could not be determined, because the invoice is damaged at that spot. The missing date must have fallen between the previous item (#14), entered August 24, 1767 and the subsequent item (#16) entered November 2, 1767. The Selectmen’s Minutes for August 19, 1767 state that, “The Firewarden acquaint the Selectmen that the Town Ladders which are now well repaired , and are placed in different parts of the Town, to be ready in case of Fire, are often taken from this places, by Persons who have occasion for them; which in their Opinion makes it necessary that an Advertisement should be inserted in the News Papers forbidding such a practice.” Apparently this order was not carried out, because three weeks later, on September 9, 1767, the Minutes indicated that the “Town Clerk was again directed to publish in the several Papers the following Advertizement—Complaint having been made…” Record Commissioners, Selectmen’s Minutes (September 9, 1767), 265, 268 (August 19 and September 9, 1767). The advertisement was published verbatim from the Minutes, and with the identical layout, in the Boston Post Boy and Advertiser and in the Boston Gazette on September 14 and in the Boston Newsletter on September 10.

[14] The entries relating to the “regulation” of Negroes, Indians and Mulattos (#1, # 11) could not be found in the Selectmen’s Minutes, and may have emanated from a different source than the meetings, even though the published advertisements indicated that they were “ordered by the Selectmen.” One order to print notices of town meetings was found in the minutes, specifying Green and Russell (item #4). The other (item #10) called for the printing of circulars, but did not specify a printer. Record Commissioners, Selectmen’s Minutes, March 5 and November 24, 1766. The advertisements relating to taxation (items # 8, 14), cited as ordered by the Assessors in the advertisements, were not found in the Selectmen’s Minutes, and probably originated directly from the Assessors’ Meetings.

[15] The space in the Minutes designated for the advertisement copy is, unfortunately, blank in the published minutes. Record Commissioners, Selectmen’s Minutes, 213 (April 14, 1766).

[16] Record Commissioners, Selectmen’s Minutes, 216-217 (May 16, 1766). The printing of this announcement was given to Messers Draper.

[17] Stacy Schiff, The Revolutionary Samuel Adams (New York, Boston, London: Little, Brown and Company, 2022) 104.

[18] Record Commissioners, Selectmen’s Minutes, 282-283 (February 10, 1768).

[19] “Colonial Newspaper Advertising Rates,” boston1775.blogspot.com/2017/06/colonial-newspaper-advertising-rates.html.

[20] The digitized newspaper images were downloaded from the Readex website (readex.com). Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers, infoweb-newsbank-com.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/apps/readex/doc? The length of each published item in millimeters (Table 1, column 8), was compared to the full length of the same newspaper column, and converted to a decimal fraction of a full newspaper column length (Table 1, column 9). To derive the cost per column length (Table 1, column 11), the cost of each advertisement (column 10) was divided by the decimal fraction (column 9). For items that had appeared on page 1 of the newspaper, where the full column length was foreshortened by the masthead of the newspaper, a median column length of 26.7 mm. was used.

[21] A similar principle seems to be operative in an example of published advertising prices appearing in the New Jersey Gazette, first published in 1777. “Advertisements of a moderate Length are inserted for Seven Shillings and Nine-pence each the first Week, and Two Shillings and Six-pence for every Continuance, and long Ones in Proportion. New Jersey Gazette, December 5, 1777, cited by Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America (New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 522-523.

[22] Record Commissioners, Selectmen’s Minutes, 273 (November 2, 1767). Samuel Sewall was one of the seven Selectmen in 1767.

[23] In the Minutes of the Selectmen’s Meetings, the orders to print circulars announcing upcoming town meetings usually specified which printer to use. For one invoice item (#4) the minutes indicated, “Voted, that Messrs. Green and Russel have the printing of the Notifications for the ensuing Town Meeting.” For the other item (#10) an order for printing the circulars was given, but without a printer specified. Record Commissioners, Selectmen’s Minutes, 211, 237 (March 5 and November 24, 1766).

[24] Record Commissioners, Selectmen’s Minutes, 170 (May 16, 1765).

[25] Arthur M. Schlesinger, “The Colonial Newspapers and the Stamp Act,” The New England Quarterly 8, no. 1 (1935): 81. Adelman, Revolutionary Networks, 13-16.

[26] New Year’s wish from the carrier of the Boston Post Boy and Advertiser (Boston: Printed by Green and Russell, 1765); New Year’s wish from the carrier of the Boston Post Boy and Advertiser (Boston: Printed by Green and Russell, 1766).

[27] Dickinson, a Philadelphia lawyer “posing” as a simple and patriotic farmer, had published a series of twelve letters in as many weeks in two Philadelphia newspapers, and signed them “A Farmer.” In the letters, Dickinson argued on constitutional lines that the British Parliament had no right to tax its colonies without their consent.

[28] While The Boston Post Boy and Advertiser carried the town’s insert thanking the author of the Farmer letters, they did not print the letters themselves. In contrast, the Boston Gazette, Boston Evening Post and Boston Chronicle printed both. This undoubtedly reflected caution on the part of printers Green and Russell, not wanting to alienate the governmental agencies that helped fund them, in particular, the new and powerful American Customs Board. In a memorial to the Customs Board several years later, in April 1772, John Green and Joseph Russell recounted how in 1768 they had sought the Customs Board’s counsel on whether to print the Farmer’s letters and were advised informally not to. They claimed, consequently, that they “soon lost the largest part of the Subscribers, by which and other Circumstances it was so reduced that they have certainly lost Money by it every year since.” Adelman, Revolutionary Networks, 13-16, 92; O.M Dickerson, “British Control of American Newspapers on the Eve of the Revolution,” The New England Quarterly 24 (1951): 455-456.

[29]Adelman, Revolutionary Networks, 81-82, 91.

Recent Articles

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

The Killing of Jane McCrea

The American Princeps Civitatis: Precedent and Protocol in the Washingtonian Republic

Recent Comments

"The American Princeps Civitatis:..."

I enjoyed this excellent article, thank you very much.

"Decoding Connecticut Militia 1739-1783"

Hi, I'm looking for discussion in the records for troop movement and...

"General Israel Putnam: Reputation..."

Gene, see John Bell’s exhaustive Analysis, “Who Said ‘Don’t Fire Till You...