The Continental Congress directed the organization of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (Rawlings’ regiment) in resolutions dated June 17 and 27, 1776.[1] The force was a combination of six newly-formed companies from the two states and three independent rifle companies organized a year before. The nine-company regiment was still completing organization on November 16 when approximately two-thirds of its 420 officers and enlisted men were captured or killed at the Battle of Fort Washington.[2] In the battle’s aftermath, the officers struggled to replenish the regiment’s numbers, and it never returned to full strength.

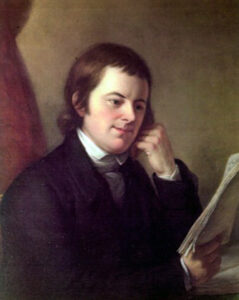

The effort to rebuild the unit was set in motion when its commander, Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings, returned to the Continental army in January 1778, having been exchanged after his capture at Fort Washington. He was initially without a command because his remaining troops had been attached to Col. Daniel Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps in mid-1777 and to the 4th Maryland Regiment in late 1777.[3] On March 27, however, the Council of Maryland formally recommended to the Board of War that Rawlings command the Maryland militia guard at the prisoner-of-war camp at Fort Frederick, western Maryland.[4] Rawlings accepted the position, but he struggled to maintain an adequate guard primarily because of the lack of a consistently trained and dedicated militia force. Beginning in the late spring of 1778, he started replacing the militiamen with Continental army recruits and a few of his regiment’s recently exchanged prisoners of war.[5]

Rawlings’ effort to gradually add enlistees to his renewed army command met only with limited success. On October 9 Congress issued a proclamation to help him with the process:

That if any of the states in which Colonel Moses Rawlins shall recruit for his regiment shall give to persons inlisting in the same, for three years, or during the war, the bounty allowed by the State, in addition to the continental bounty, the men so furnished, not being inhabitants of any other of the United States, shall be credited to the quota of the State in which they shall be inlisted.[6]

This unusual ruling permitted Rawlings and his remaining officers to recruit outside Maryland. Any non-Marylander who enlisted for three years or the duration of the war, and who was not an inhabitant of any other of the United States, would receive both the bounty (enlistment bonus) of the state in which he enlisted and the continental bounty. Congress also would give that state credit toward their Continental Army troop quotas for any recruits they provided. Implementation of the resolution nonetheless failed to significantly increase the regiment’s numbers, reflecting the Continental army’s pervasive recruitment difficulties at this time of the war.[7]

Washington initiated more definitive measures to strengthen the regiment in early 1779 when he asked Congress to reorganize the unit into three companies, each with a full strength of about sixty men. On January 23, Congress approved both the restructuring and the regiment’s reassignment from Fort Frederick to Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), headquarters of the Continental army’s Western Department.[8]

As part of the reorganization, Washington requested in his general orders of February 16 that

all the men belonging to Lieutenant Colonel Rawlings’s Regimt. now doing duty in the line are to be delivered up to Lieutenant Tanneyhill of said regiment upon his demanding them.[9]

Washington directed all personnel on detached assignment to report to 1st Lt. Adamson Tannehill for reintegration into the regiment. The enlisted men who had been attached to the 4th Maryland Regiment throughout 1778 rejoined Rawlings’ regiment, their permanent unit.[10] Those attached to Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps were unable to return because the corps was on specialized duty in New York State, not with the main army when the recall order was issued.[11] Rawlings’ force was now composed almost entirely of Marylanders because soon after the Battle of Fort Washington, the Council of the State of Virginia had ordered the incorporation of the Virginia elements of the unit into the Virginia line.[12]

Washington implemented the reorganization on March 21, 1779. In his letter to Rawlings that day, he specified that:

I have desired the Board of War to call upon Govr. Johnson to furnish a Guard of Militia to relieve you — As soon as the Relief arrives you are to march with all your men fit for duty to Fort Pitt and after your arrival there take your orders from Colo. Brodhead who now commands in the Western department — You will leave officers to proceed in recruiting your Corps to the establishment.[13]

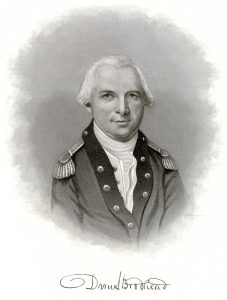

Washington wanted Maryland Governor Thomas Johnson, commander of his state’s militia, to have the militia take over guard duties at Fort Frederick so that Rawlings’ soldiers could be freed for other service. Rawlings and his men then were to proceed to Fort Pitt and report to Western Department commander Col. Daniel Brodhead to help in the defense of frontier Pennsylvania settlements from raids by British-allied Indian tribes.[14] Washington also instructed Rawlings to leave officers behind in Maryland, where they would continue recruiting from bases at Fort Frederick and Fort Cumberland.[15] The two forts were located about fifty miles apart in the western part of the state. Every new recruit would receive a bounty of 200 dollars, and the recruiting officers were each entitled to twenty dollars per recruit and three dollars a day for expenses.[16] Capts. Thomas Beall and Adamson Tannehill supervised the recruiting process.

The two officers faced continuing challenges in recruiting for their regiment in Maryland in early 1779. In mid-March, Washington reported to Congress that the regiment had made no progress in this regard because of the inferiority of the Continental bounty to that of the state of Virginia.[17] At this time, inducements to enter the service in the form of higher bounties and shorter terms of duty offered by the Virginia state government adversely affected recruiting in nearby states. With the arrival of spring a month later, Governor Johnson notified Washington of Rawlings’ success in enlarging his three-company regiment to approximately 100 men.[18] But in mid-1779 the unit lost about half of its troop strength because the three-year enlistment periods of those men who had joined the regiment during its organization in mid-1776 had terminated.[19]

On March 26, 1779, the Maryland General Assembly advanced an initiative to address the recruitment difficulties. In its letter to Washington, the Council of Maryland provided a concise summary of the proposal:

We have the Honor to inclose you [a] Resolution . . . of the General Assembly passed Yesterday before their Adjournment and hope that our Parts of the Rifle and German Battalions may be incorporated without Inconvenience or Difficulty. The Merits and Services of many of the Officers, we have no Doubt will make any Instances of ours to place them in the same advantageous Situation as others, unnecessary.[20]

The resolution advocated the consolidation of Rawlings’ rifle regiment and the German Battalion, both of which included soldiers recruited from Maryland. The General Assembly expected that the distinguished service of the officers of the two units would be sufficient to ensure their proper placement within the proposed new arrangement.

In response, Washington wrote to Governor Johnson on April 8 offering a point-by-point critique of the proposal:

I have been honored with yours of the 26th March inclosing a Resolve of the House of Delegates for the incorporation of [the Maryland] parts of the German Battalion and Rifle Corps into a Regiment. . . . By an allotment of the quota of troops to be raised by each State, made by Congress the 26th Feby 1778, the German Battalion was wholly attached to the State of Maryland and considered as her Regt since which it hath done duty in that line. Had not this been the case, the incorporation of such parts of that Regiment and [Rawlings’] Rifle Corps as are deemed properly to belong to Maryland would still be attended with the greatest inconveniences, particularly in regard to reconciling the Ranks of the Officers, Colo Rawlins and most of his being elder than Colo Weltner and those of the German [Battalion] would supersede them upon incorporation. Indeed Colo Weltner would not only be superseded, but he must be supernumerary. In short, the difficulties attending the measure recommended are more than can be conceived, and I am convinced by experience that it cannot be carried into execution without totally deranging the German Regiment.[21]

Like Rawlings’ regiment, the German Battalion partly consisted of Maryland troops. Both units were formed as extra Continental regiments that had no administrative connection to the state of Maryland, only to Congress. As of February 26, 1778, though, Congress officially made the Maryland contingent of the German Battalion part of the Maryland line, whereas Rawlings’ regiment remained outside the state line.[22] As Washington explained, this would cause significant administrative and command issues that would prevent the units from merging smoothly. The incorporation of the units also would have made battalion commander Lt. Col. Ludwig Weltner and at least some of his officers supernumerary (redundant), likely leading to Weltner’s forced resignation and the total disorganization of the battalion. Consequently, Washington rejected the proposed idea.

After recruitment for the regiment was only partially completed and replacements from the Maryland militia for duty at Fort Frederick had been assembled, Rawlings’ men (including Captains Beall and Tannehill) set off for Fort Pitt, arriving there on May 28, 1779.[23] Five days later, Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings resigned his command of the rifle regiment, and Capt. Thomas Beall, as senior officer, assumed formal control, with Capt. Adamson Tannehill becoming second in charge.[24] In a memorial from Rawlings to Congress, dated November 28, 1785, the regimental commander summed up his grievance:

On your memorialist’s exchange he found his efforts to collect his regiment ineffectual and that he was drawing pay without doing duty; he therefore determined to resign which he did in June 1779.[25]

Rawlings’ frustration over his inability to rebuild the regiment was probably exacerbated by Washington’s refusal to permit the Maryland contingent of the German Battalion to merge with his unit and accompany him to Fort Pitt. The return of Beall and Tannehill from their largely ineffectual recruiting tour in Maryland five days before Rawlings’ resignation also probably contributed to his dissatisfaction.

The rifle regiment, now commonly identified as the Maryland Independent Corps in period documents, complemented the existing garrison of infantrymen at Fort Pitt: the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment commanded by Col. Daniel Brodhead and the 9th Virginia Regiment under Col. John Gibson.[26] Brodhead’s men, recruited from the central and western frontier counties of Pennsylvania, and Gibson’s force, which consisted of troops from the far-western Virginia counties (now parts of West Virginia and western Pennsylvania), were assigned to the army’s Western Department while at Valley Forge. Washington had a clear rationale: the addition of Rawlings’ troops to Fort Pitt gave Brodhead a considerable fighting force of frontiersmen who were versed in Indian-style woodland tactics.

With Captains Beall and Tannehill now at Fort Pitt, recruitment for the regiment in Maryland came to a virtual standstill. Later personnel changes on the Pennsylvania frontier were rare and typically involved the promotion of men from Rawlings’ unit who transferred to the 9th Virginia Regiment at Fort Pitt.[27] A composite muster roll of Rawlings’ regiment at Fort Pitt for the ten months from January through October 1780 shows that three commissioned officers served in the unit during this period.[28] The roll also records that the much-reduced rifle regiment consisted of only sixty enlisted men.

In a rambling letter addressed to Maryland governor Thomas Sim Lee and the Council of Maryland dated August 30, 1780, Beall described his personal involvement in recruiting a British prisoner of war that February:

I . . . weightd on the Comdr for orders he then told me he had understood I had Inlisted A british Prisoner of war. I acknoledgd I had. . . . I expected as the Comdr had disapprovd of his Inlistment and I being Commanding Officer of the Core it was my duty to discharge him and as I inlisted him the Money and Clothing then lay at my Risk and as [the enlistee, named McCleod] had spent the Money and defacd the Clothes took the first oppertunity to Discharge him. . . . The Comdr then in presence of Capt Tannehill said he had disapprovd of his Inlistment and if he knew of any prisoners there he wood imediately have them sent of and told me he wood order a Cort of Inquiry and I shood have a hearing. . . . Capt Tannehill Amediately returnd to his Quarters and made out a report and had me Arested . . . The Clothing [McCleod] had Receivd was paid him as part of his Bounty and in the publick manner. I dischargd him am Affraid the Matter has gone Against me. I acknowledge I have done Rong in [enlisting] the Fellow.[29]

Facing continual pressure to maintain troop strength, regimental commander Beall violated Continental army regulations by approving the enlistment of a British prisoner of war. His crime, however, was that he sought to remedy his error in judgment by dismissing the recruit, despite the fact that the recruit had already received his recruitment bounty and uniform.[30] On August 14, at Fort Pitt, Captain Beall was tried by court-martial and found guilty of “discharging a Soldier after having been duly inlisted and receiving his regimental cloathing through private and interested views thereby defrauding the United States.”[31]

On October 13, Washington dismissed Captain Beall from the service. Capt. Adamson Tannehill then took over command of the regiment until its disbanding on January 1, 1781.

The officers of Rawlings’ regiment faced a number of obstacles in their attempt to recruit for the unit. Among them were deficiencies in their recruitment bounties compared to those of neighboring Virginia, ill-timed expiration of enlistment periods, the remote duty location, and the official technical status of the regiment. The last issue was the most impactful and complex. As an extra Continental regiment, Rawlings’ unit was not part of the state’s official quota of regiments in the Maryland line. This caused problems related to rank, pay, promotion, and recruitment because officers of non-line regiments had, among other factors, fewer opportunities for advancement than their counterparts in the regular Maryland line. Washington highlighted this issue in his April 8, 1779, letter to Maryland governor Thomas Johnson:

I entertain a very high opinion of the merits of Colo Rawlins and his Officers, and have interested myself much in their behalf. It is to be regretted that they were not provided for in the States to which they belong, when the Army was new modelled in 1776, but as they were not, after a variety of plans had been thought of . . . the introduction of those Gentlemen into the line would have been impracticable.[32]

While Rawlings and most of his men were held as prisoners of war after the Battle of Fort Washington, Congress approved a major reorganization of the Continental army in 1776, which included a resolution on December 27 that granted Washington the authority to raise additional regiments within each state.[33] As a result, Maryland committed to raising a new state line regiment that would unite the state’s portions of Rawlings’ regiment and the German Battalion.[34] However, the state never completed the unit’s organization.[35] As in the later congressional resolve of February 26, 1778, Rawlings’ riflemen thus were not integrated into the Maryland line.[36]

Unlike state line soldiers who were officially credited to their home state’s quota and guaranteed its benefits, Rawlings’ recruits did not receive the same promised state-level recruitment support and clothing allowances. Moreover, Maryland state resources, including county committees, could not be used to help fill the ranks of Rawlings’ regiment. Congress tried to compensate for this in the two resolutions of late 1776 and early 1778, but they both failed to bring the regiment into the state-line arrangement. Despite the best efforts of Washington, Congress, Governor Johnson, and the regiment’s officers to secure new recruits, Rawlings’ rifle regiment remained consistently understaffed after the battle of Fort Washington until it was ultimately disbanded.

[1] Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Library of Congress, 1906), 5:452, 486.

[2] Memorial of Moses Rawlings (August 1778), Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, RG360, M247, Roll 51, Item 41, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

[3] Payrolls of Capt. Gabriel Long’s Co. of Detached Riflemen Commanded by Col. Daniel Morgan (July 1777 through May 1778), War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG93, M246, roll 133, folder 226, NARA. Muster Rolls of Capt. Alexander Lawson Smith’s Company Including Part of the Companies Belonging to the Regiment of Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings under the Command of Col. Josias Carvell Hall of the 4th Maryland Regiment (January through December 1778), Revolutionary War Collection, Maryland Historical Society, MS 1814.

[4] Council of Maryland to Horatio Gates (March 27, 1778), in William Hand Browne, ed., Archives of Maryland: Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Safety, January 1, 1777–March 28, 1778 (The Friedenwald Co., 1897), 16:555–556.

[5] Council of Maryland to Daniel Hughes (June 24, 1778), in Archives of Maryland, 21:148.

[6] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 12:993.

[7] Robert K. Wright, Jr., 1983, The Continental Army (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 125–126.

[8] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 13:104.

[9] General orders, February 16, 1779, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 3.

[10] Alexander Lawson Smith’s Co. 1778 Muster Rolls, Maryland Historical Society, MS 1814.

[11] Payrolls of the Late Capt. Gabriel Long’s Co. of Detached Rifle Men Formerly Commanded by Col. Daniel Morgan (April through September 1779), War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG93, M246, roll 133, NARA.

[12] Council of Virginia Meeting, February 3, 1777, in Henry R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia (The Virginia State Library, 1931), 1:320–324.

[13] George Washington to Moses Rawlings, March 21, 1779, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 4.

[14] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 15:1212–1213.

[15] Pension application of Basil Shaw, S.16,526, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, RG15, M804, roll 2160, NARA.

[16] Washington to Rawlings, March 7, 1779, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 4.

[17] Washington to Congress, March 15, 1779, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 4.

[18] Thomas Johnson to Washington, April 23, 1779, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 4.

[19] Daniel Brodhead to Washington, May 29, 1779, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 4.

[20] Council of Maryland to Washington, March 26, 1779, in Archives of Maryland, 21:329.

[21] Washington to Johnson, April 8, 1779, in Archives of Maryland, 21:339–340.

[22] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 10:200.

[23] Brodhead to Washington, May 29, 1779, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 4.

[24] Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army (The Rare Book Shop Publishing Co., 1914), 459.

[25] Memorial of Moses Rawlings, November 28, 1785, Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, RG360, M247, Roll 51, Item 41, NARA.

[26] Brodhead to Washington–Return of Troops in the Western Department, April 17, 1779, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 4.

[27] Names and Rank of the Field, Staff, and other Commissioned Officers of Col. John Gibson’s Detachment, who served in the Western Department, January 1, 1780, to December 6, 1781, in William T. R. Saffell, ed., Records of the Revolutionary War (Pudney & Russell, 1858), 280. For example, Adj. Josiah Tannehill transferred from Rawlings’ unit to Col. John Gibson’s 9th Virginia Regiment in August 1779, becoming a commissioned officer with the rank of ensign.

[28] Thomas Beall’s Muster Roll, January through October 1780, in Archives of Maryland, 18:350–351.

[29] Thomas Beall to Thomas Sim Lee and Council of Maryland, August 30, 1780, in Archives of Maryland, 45:69–70.

[30] Ibid.

[31] General orders, October 13, 1780, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 3.

[32] Washington to Johnson, April 8, 1779, in Archives of Maryland, 21:339–340.

[33] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 6:1043–1046.

[34] Wright, The Continental Army, 99.

[35] Ibid., 100–101.

[36] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 10:200.

One thought on “Vanishing Ranks: Rawlings’ Rifle Regiment and the Struggle to Recruit for the Frontier”

Good work here. This being one of the harder units to research, your efforts are appreciated.