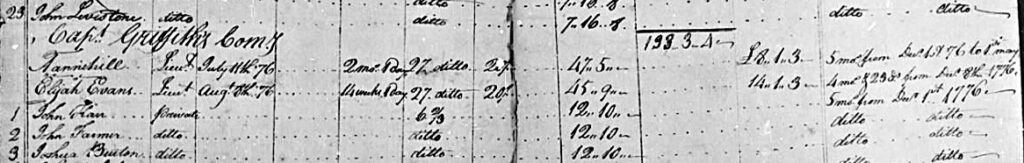

On Christmas day 1780, seven days before his discharge from the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (Rawlings’ regiment), Lt. Elijah Evans recorded in a troop return that he “claims a Captaincy from the 15th April 1779.”[1] This was his last attempt to highlight a conspicuous administrative oversight that had prevented his promotion throughout his time in the Continental army. His grievance stemmed from two issues: the unusual formation and complex service history of Rawlings’ regiment, and a protracted debate between the state of Maryland and the Board of War over his official administrative status after the Battle of Fort Washington in November 1776.

Evans, a Marylander, served as a third lieutenant in Rawlings’ regiment for four years and five months beginning in August 1776. During his service, he was also attached to Col. Daniel Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps for two years from late 1777 to late 1779. In fact, by the spring of 1779, Evans commanded one of the two remaining companies of Morgan’s rifle corps still in the field. In spite of his long and active military career that included this command duty, he retained the rank of third lieutenant throughout his tenure in the army ending in January 1781.

Service History

Rawlings’ regiment was organized by congressional decrees on June 17 and 27, 1776.[2] They directed that three of the independent rifle companies from Maryland and Virginia, formed as part of the creation of the Continental army in June 1775, be supplemented with six new companies enlisted for three years—two from Maryland and four from Virginia. The unit was formed as an Extra Continental regiment, one of six in the Continental army authorized by Congress and organized in late 1775 to mid-1776.[3] It was an “extra” regiment, not part of a state line organization, because of its two-state composition. This arrangement prevented the regiment from being managed by a single state government, and therefore it had an administrative connection only to national authority (i.e., Congress and the Continental army).

The entire force of nine companies was organized on the same structure as the Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment, later designated the 1st Continental Regiment.[4] On June 29, Congress ordered the two colonial governments to raise their new companies and appoint the officers as rapidly as possible.[5] The new force would be called the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment, with Virginian Hugh Stephenson as colonel and Marylanders Moses Rawlings and Otho Holland Williams as the lieutenant colonel and major, respectively.[6] Colonel Stephenson died of illness soon thereafter and was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Rawlings as regimental commander. Elijah Evans’ Maryland company was commanded by Capt. Philemon Griffith, with Thomas Hussey Luckett, Adamson Tannehill, and Henry Hardman as his subordinates. Third Lieutenant Hardman resigned shortly thereafter, leading to a new commission granted by Congress on September 17, 1776, to Elijah Evans.[7] His date of rank was set retroactively at August 8, twenty-eight days after those of the other officers in Griffith’s company.[8]

Elijah Evans was one of the officers who traveled back to Maryland in the midsummer of 1776 to recruit for Griffith’s company. By going to Maryland to recruit replacements, Evans was entitled to compensation for the rations (subsistence) that he missed by not being with his company when it drew its food, and his unit’s first payroll compiled after his return shows that he drew such pay.[9] Direct notations in the payroll indicate that Evans received subsistence pay for three and a half months, the total time he spent recruiting in Frederick County, his home county. Lieutenant Evans and his recruits returned to New York in time to participate in the Battle of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776. During the conflict, most of Rawlings’ riflemen were defending the area north of the fort from Hessian infantry. After almost a day’s fighting, the riflemen were driven back to the fort where the American garrison surrendered. Although most of the riflemen were taken prisoner, Elijah Evans was “wounded but made his retreat good over the north [Hudson] River.”[10] After recovering from his wounds, Evans returned to the main army and Rawlings’ regiment on December 8 in time to participate in the Trenton-Princeton campaign.[11]

In early December 1776, Gen. George Washington provisionally grouped the Maryland and Virginia remnants of Rawlings’ regiment not captured at Fort Washington into two composite rifle companies commanded by the unit’s highest-ranking officers still free—Capts. Alexander Lawson Smith and Gabriel Long.[12] Long’s composite company comprised all the Virginians still at liberty, while the Marylanders formed the core element of Smith’s composite company, which included Philemon Griffith’s unit (with Elijah Evans). There are few records of this small element during the chaotic period of the Trenton and Princeton campaign, but as soon as the situation stabilized in northern New Jersey in the spring of 1777, steps were taken to provide a clear paper accounting. On May 1, the army staff prepared a payroll for Smith’s composite company, carrying all relevant data for the period December 1, 1776, to April 30, 1777.[13]

At the army’s Morristown, New Jersey, winter encampment in early April 1777, Washington administratively attached the two composite companies to the newly organized 11th Virginia Regiment.[14] As a result, the army staff compiled the companies’ first payrolls and muster rolls since the Battle of Fort Washington. By this time, Daniel Morgan, captain of one of the independent rifle companies of Virginia formed in 1775, had been promoted to colonel, and he assumed command of the 11th Virginia. (Washington also made Morgan commandant of the new Provisional Rifle Corps in June.[15] Thus, Morgan simultaneously commanded the 11th Virginia and his rifle corps—one permanent unit, one provisional.) The permanent incorporation of Capt. Gabriel Long’s composite company into the 11th Virginia Regiment had also been ordered by the Council of the State of Virginia in early February 1777.[16] No such decree came from the Maryland state government or Congress for the permanent incorporation of Capt. Alexander Lawson Smith’s composite company, including Lt. Elijah Evans, into the Maryland line. Instead, it served as an attached unit in the 11th Virginia throughout the Philadelphia campaign of 1777. It was then attached to the 4th Maryland Regiment starting in the latter part of the year and extending through 1778.[17]

In November 1777, Evans temporarily left Rawlings’ regiment (his permanent unit) after being administratively attached to Col. Daniel Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps.[18] Muster rolls and payrolls document that at least thirty-five officers and enlisted men of Smith’s and Long’s composite companies (including Gabriel Long himself) had been selected to join this regiment-sized force of about 500 men in mid-1777. After Washington’s comprehensive effort to increase the organizational efficiency of the Continental army, he reduced Morgan’s rifle corps to two companies in July 1778, just after the Battle of Monmouth.[19] Washington then placed the corps under the command of Capt. Thomas Posey and later Maj. James Parr, both veterans of the unit.[20] All members of the provisional rifle corps not retained in these two companies returned to their permanent units. Among those who remained in the rifle corps was Lt. Elijah Evans.

In April 1779, Evans became the commanding officer of the sixty-five-man company formerly led by Capt. Gabriel Long (who resigned from the corps in mid-May).[21] Evans’ unit was one of two companies of the rifle corps that served in the Sullivan Expedition of June through October, which fought to suppress the activities of enemy Iroquois and Loyalist units in southern and western New York State. The most noteworthy operation in which Evans’ riflemen played a prominent role was the raid on the Indian villages of Unadilla and Onaquaga in early October.[22] After the campaign Evans’ detached duty in Morgan’s rifle corps ended with the formal disbanding of the unit in early November 1779.[23] At that time, Washington ordered all members of the rifle corps to return to their permanent regiments.

Four days later Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman, Washington’s aide de camp, wrote to Deputy Paymaster General John Pierce:

the Rifle Corps under the command of Major Parr has been so detached that they have never been regularly mustered. But as they are about to be dissolved His Excellency desires that you will grant Warrants for their pay up to the 1st of October upon the Abstracts certified by Major Parr.[24]

The provisional and dispersed nature of the corps prevented it from being given a formal muster. Indeed, no muster rolls for Morgan’s rifle corps were taken during its entire two-and-a-half-year existence. The lack of musters likely contributed to Elijah Evans’ failure to be promoted, even after taking on his new command.

By early 1780 Evans had rejoined Rawlings’ regiment in western Pennsylvania where they had been supporting other Continental forces defend frontier settlements from raids by British-allied Indian tribes.[25] In early 1779, the regiment had been reorganized and reduced to three companies and deployed to Fort Pitt.[26] Because the regiment’s Virginians already had been formally incorporated into the 11th Virginia Regiment, Rawlings’ regiment now consisted of mostly Marylanders and was most commonly identified informally as the Maryland Corps.

In January 1781, Washington and Congress instituted a comprehensive reorganization of the Continental army to reduce expenditures and increase organizational efficiency.[27] All Extra Continental regiments such as Rawlings’ that had not been annexed to a state line organization were disbanded.[28] Lt. Elijah Evans and the other regiment’s officers received honorable discharges on January 1, 1781.

Unresolved Issues

Because the Maryland state government had not incorporated the Maryland members of Rawlings’ Extra Continental regiment into its line units, much discontent existed among the regiment’s Maryland officers who had been confined as prisoners of war after the Battle of Fort Washington. Their objection was that they had not been promoted while in captivity, even though Continental army policy dictated that they should have been if their unit had been in the Maryland line. On January 20, 1781, the Maryland State Council presented the officers’ grievances to the Board of War, Congress’ special standing committee to oversee the Continental army’s administration and make recommendations regarding the army, including those related to promotions:

We are requested by the General Assembly to represent to the Board over which you have the Honor to preside that Thos. Hussey Luckett first Lieutenant in the first Company, James Lingan second Lieutenant in the ninth Company, Rezin Davis third Lieutenant in the second Company and Elijah Evans third Lieutenant in the first Company of Colonel Rawlings’ Regiment were made Prisoners of War at Fort Washington in November 1776, and that during their Captivity they were neglected in the general Arrangement of the Officers of the Maryland Line which hath since taken place and have also lost their Advancement in said Regiment in Consequence of which officers of inferiour Rank to them in the Line and in that Regiment have been preferred and now hold Commissions superior to theirs and to request that your Honorable Board would take such order therein that said Officers may be preferred to such Commissions as their preceding Rank will entitle them to and that no further Promotions in the Maryland Line be made without previously consulting the State.[29]

Lieutenants Luckett, Lingan, and Davis had all been captured and not exchanged until 1778.[30] But Evans was a special case because he was not taken prisoner in the battle. This made the situation particularly vexing for him and confusing for the Maryland State Council, which considered the officers to be members of the Maryland line.

Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings expressed a similar grievance about seven months after his exchange as a prisoner of war. He wrote

that on the 16th of November, 1776 your Memorialist together with all the officers and privates under his Command were either Killed wounded or taken Prisoner at Fort Washington; that during his confinement with the Enemy the States Adopted the method of Alloting to each Colony or Province the number of Regiments they were deemed Capable of raising towards filling up the Continental Army, in complying with which allotment your Memorialist & his Regiment have been totally overlooked, neglected, or forgot, by the State of Maryland, so that he and the officers under his command are quite out of the Line of Promotion by the new Arrangement of the Army. . . . If your Excellency thinks the Peculiar Situation of your Memorialist & his officers, Merits and admits any Relief and your Excellency will take the same under consideration your Memorialist as in duty bound shall pray &c.[31]

In late 1778, Evans’ first company commander, Capt. Philemon Griffith, resigned from the service soon after his exchange as a prisoner of war. In his 1832 pension claim he expressed thoughts comparable to those of his comrades on the effects of his imprisonment and the inability of the army to provide for him after his exchange:

That on the 16th day of November 1776, this Deponent and others were made captives by the British, and so remained until the year 1778. That the said Deponent being released from confinement in the latter part of the spring of the last named year, and finding upon application that he was not provided for in the then existing continental line of the revolutionary army, and no prospect of any such provision taking place, retired from service with the said Col. Rollins, by resignation in the latter part of the said year of 1778.[32]

While Rawlings, Griffith and most of the regiment’s other officers were confined in 1776, Congress approved a major reorganization of the Continental army which included a resolution on to grant Washington the authority to raise additional regiments within each state.[33] As Rawlings indicated in his memorial, even though the state of Maryland raised its allotment of additional regiments as a result of this reorganization, the officers of Rawlings’ regiment were denied any recourse during their time as prisoners of war. Continental army policy protected the interests of officers while they were in enemy hands by tracking when they would have been promoted if they had been free. It then made those promotions retroactively after the officer received his freedom.[34] Rawlings did not fully understand the administrative nature of his unit’s status—he incorrectly believed that the Maryland portion of his Extra Continental regiment was part of the Maryland line. His argument, like that of the Maryland State Council, suggesting that retroactive promotions be granted to his officers, was erroneous, although understandable.

The false perception of the Maryland State Council that Elijah Evans was a prisoner taken at Fort Washington greatly hindered his promotion prospects. Those prospects were further complicated by his complex service history, notably his provisional two-year stint in Morgan’s rifle corps, creating administrative confusion within the army over his service record. The fact that the Maryland portion of his regiment had not been incorporated into the Maryland line was probably the predominant reason for Evans’ static rank. The procedure for promotion in the Continental army was that state councils recommended advancements based on the direction of the officers’ county officials and then sent a list of promoted officers and their dates of rank to the Board of War and Congress for final approval and processing. Although the Maryland council considered Evans to be an officer in the state line, the Continental army and Board of War did not, and he was therefore, as Rawlings expressed, effectively “quite out of the Line of Promotion” during the war.

Closing Reflection

By all available accounts, Lt. Elijah Evans engaged in an uninterrupted and successful career in the Continental army, progressively advancing in responsibilities and honorably serving in Rawlings’ regiment and Col. Daniel Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps for almost four and a half years. Although he was never promoted beyond third lieutenant, he still achieved a noteworthy command position in the army. On May 25, 1789, the federal government granted him 300 acres of bounty land “on account of his services as a Captain of the Maryland troops.”[35] Although no record of it has been found, one can only surmise that the state of Maryland and Board of War finally resolved Evans’ claim to captaincy soon after his discharge in early 1781.

[1] Return of the Commissioned Officers of the Maryland Corps (Late Rawlings’s) Specifying their Names, Ranks, Claims to Promotion, etc., December 25, 1780, Archives of Maryland, Maryland State Papers, series A, box 21.

[2] Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Library of Congress, 1906), 5:452, 486.

[3] Robert K. Wright, Jr., 1983, The Continental Army (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 99, 319.

[4] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:452.

[5] John Hancock to the Maryland Convention, June 29, 1776, in Paul H. Smith, ed., Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789 (Library of Congress, 1979), 4:334–335.

[6] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:486.

[7] Ibid., 5:764.

[8] Payroll of Capt. Alexander Lawson Smith’s Co. with Part of Captain Griffith’s, Davis’ and Beall’s Companies of Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings’ Battalion of Riflemen, Now under the Command of Col. Daniel Morgan of the 11th Virginia Regiment from the Last Times of Their Receiving Pay to the 1st Day of May 1777, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG93, M246, roll 126, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (NARA).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Memorial of Moses Rawlings, August 1778, Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, RG360, M247, Roll 51, Item 41, NARA.

[11] Payroll for Alexander Lawson Smith’s Co., May 1, 1777, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG93, M246, roll 126, NARA.

[12] Payroll for Alexander Lawson Smith’s Co., May 1, 1777, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG93, M246, roll 126, NARA. Muster Roll of Gabriel Long’s Co. of Rawlings’ Regiment, May 16, 1777, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG 93, M246, roll 109, NARA.

[13] Payroll for Alexander Lawson Smith’s Co., May 1, 1777, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG93, M246, roll 126, NARA.

[14] Ibid.

[15] George Washington to Daniel Morgan, June 13, 1777, in Frank E. Grizzard, Jr., ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (University Press of Virginia, 2000), 10:31.

[16] Council of Virginia Meeting, February 3, 1777, in H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia (The Virginia State Library, 1931), 1:320–324. The state of Virginia had exceeded its authority in this action, which was technically only within the purview of Congress and Washington, who tacitly accepted the arrangement.

[17] Muster Rolls of Capt. Alexander Lawson Smith’s Company Including Part of the Companies Belonging to the Regiment of Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings under the Command of Col. Josias Carvell Hall of the 4th Maryland Regiment, January through December 1778, in Revolutionary War Collection, Maryland Historical Society, MS 1814.

[18] Payrolls of Capt. Gabriel Long’s Co. of Detached Riflemen Commanded by Col. Daniel Morgan, July 1777 through May 1778, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG93, M246, roll 133, folder 226, NARA.

[19] Wright, The Continental Army, 146.

[20] Return of the Rifle Corps under Capt. Thomas Posey, July 28, 1778, in Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York (State of New York, 1900), 3:588.

[21] Payrolls of the Late Capt. Gabriel Long’s Co. of Detached Rifle Men Formerly Commanded by Col. Daniel Morgan, April through September 1779, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG93, M246, roll 133, NARA. Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army (The Rare Book Shop Publishing Co., 1914), 356.

[22] Glenn F. Williams, Year of the Hangman: George Washington’s Campaign Against the Iroquois (Westholme Publishing, 2005), 168–171.

[23] General orders, November 7, 1779, in George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 3, Subseries G, Letterbook 4.

[24] Tench Tilghman to John Pierce, November 11, 1779, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, RG 93, M246, Roll 133, NARA.

[25] Muster Rolls of the Maryland Corps in the Service of the U. States, Commanded by Capt. Thomas Beall, January through October 1780, in Archives of Maryland: Muster Rolls and Other Records of Service of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution, 1775–1783 (Maryland Historical Society, 1900), 18:350–351.

[26] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 13:104. No unit-redesignation orders accompanied the reorganization orders; therefore, the unit’s formal name remained the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment despite significant variations from the unit’s original 1776 configuration.

[27] Wright, The Continental Army, 153.

[28] General orders, November 1, 1780, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 3, Subseries G, Letterbook 5.

[29] Maryland State Council to President of the Board of War, January 20, 1781, in Bernard C. Steiner, ed., Journal and Correspondence of the State Council of Maryland, 1780–1781 (Maryland Historical Society, 1927), 45:283-284.

[30] Memorial of Moses Rawlings, August 1778, RG 360, M247, Roll 51, Item 41, p. 365, NARA.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Pension application of Philemon Griffith, S.8617, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, RG15, M804, roll 1134, NARA.

[33] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 6:1043–1046.

[34] Robert K. Wright, Jr., personal communication.

[35] Pension application of Elijah Evans, B.L.Wt. 673-300, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, RG15, M804, roll 939, NARA.

2 Comments

Thank you for this excellent and interesting article!

Great research here!