As his London Packet approached the colonies in November 1774, Thomas Paine was not scanning for land. After turning northwards towards Philadelphia in Delaware Bay, the former privateer was not visualizing where, during the Seven Years War, French privateer ships awaited English prey within the folds of the eastern shore.[1] Stricken with typhus fever that had ravaged his ship, the delirious and barely conscious Paine was confined to his cabin.[2]

Dr. John Kearsley, Jr., taking him on as a patient, had him brought “on Shore” and “provided a Lodging.”[3] Paine later reported to Benjamin Franklin, whose letter of introduction graced Paine’s meager belongings, that six weeks in Kearsley’s care resulted in full recovery.[4]

Paine biographers assert that Kearsley became involved because he heard about an ill passenger with a letter from Franklin, which motivated Kearsley to have the passenger brought to him.[5] One biographer even fancifully claimed that the captain alerted Kearsley about Paine who then stayed with the captain’s family members in Philadelphia while Paine recovered.[6]

With many other doctors then practicing in Philadelphia, why Kearsley?[7] Paine provided the answer: Kearsley “attended the Ship on her Arrival.”[8] Presumably appointed by the governor under Pennsylvania law to inspect the infected ship, and learning of Paine and the Franklin letter during that inspection, he did not hear it through the grapevine.[9]

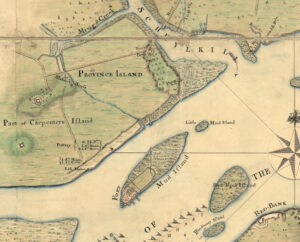

Biographers who specify where the ship docked and Paine’s care occurred assume Philadelphia locations.[10] Instead, Pennsylvania law required infected ships to moor seven nautical miles downriver, a place where those with infectious diseases were quarantined.[11] By 1743, Philadelphia built a “pest hospital” on Province Island “for the purpose of quarantining the sick who arrived by ship.”[12] The 1774 law prohibited ships “disordered with any infectious disease” from coming closer than Mud Island and required quarantine of infected persons on adjacent Province Island.[13]

Unless the ship’s captain flouted Pennsylvania law and risked severe penalties, Paine sailed no closer to Philadelphia than Mud Island and was brought “on Shore” on Province Island.[14] Regardless, Kearsley likely supported the law. Pennsylvania had long required that infected ships be cleansed with vinegar, which comported with Kearsley’s strong advocacy of the health benefits of vinegar and with significant income derived from operating a vinegar factory.[15] In a 1769 article, Kearsley, recommending “bathing the body” of putrid sore throat patients “with very strong warm vinegar, particularly the legs and thighs, throat and breast” as “an auxiliary to stop the progress of putridity,” reported his general practice of ordering “hot steams of vinegar” and other ingredients to be “drawn through a funnel into the lungs.”[16]

The mortality rate for “highly intellectual” people who contracted typhus fever, like Paine, was “very high.”[17] Paine’s delirium upon arriving heightened the prospect of death.[18]

Available evidence indicates that Paine’s ship docked downriver, he was quarantined on Province Island, and was rescued from likely death by Kearsley’s intervention and ongoing care.

Cabin “passengers” like Paine were required to pay for care and nothing required inspecting physicians to provide ongoing care, much less for free or at a discount.[19] The “Keeper” of the “hospital” was authorized to charge for a passenger’s stay.[20] Paine lacked resources to pay for his care.[21] His notation that Kearsley “provided a Lodging” during recovery likely meant that Kearsley handled charges for Paine’s “hospital” stay.[22] Caring for Paine was a considerable economic hit even if Kearsley sometimes sent his young enslaved James Derham, trained by Kearsley in medicine preparation and patient encounters, to visit Paine.[23]

Why did Kearsley decide to care for Paine over several weeks if he received no income, potentially paid hospital charges, and traveled far downriver on multiple occasions? Charity was an unlikely motivation. Providing extended care to the poor without charge was rare in the colonies.[24] If anything, Kearsley tended to prioritize his own financial pursuits over needs of the poor. Kearsley’s uncle, who died in 1772, bequeathed much of his estate to create and fund an infirmary for poor women.[25] That bequest was substantially delayed and nearly thwarted because Kearsley sued to obtain more from his uncle’s estate, his claim prevailed before a jury though legally groundless, and his uncle’s intent was realized only through additional donations by others.[26]

If Franklin’s letter of introduction was a motivator, it was not the primary one. Kearsley detested Franklin.[27] Sarcastically calling him “The Electrician,” Kearsley accused Franklin of manipulating the Assembly into appointing him to a position in England because he had a shaky hold on a Pennsylvania position and cynically predicted that Pennsylvania revenues would fund Franklin’s stay in England because “he is wicked enough to Blind the people.”[28]

The most likely rationale for Kearsley taking on Paine’s care, given subsequent events, could not be more ironic. A Loyalist who vigorously opposed American resistance to England, Kearsley was, as friends and foes perceived, “violent” in his Loyalist views and actions.[29] That was apparent before and after Paine arrived.

Issac Atwood encountered Kearsley soon after arriving from England in 1773 and Kearsley “frequently” asked Atwood to attend meetings designed to assure that all “Englishmen” associate and drink “success to British arms.”[30] Kearsley “headed” a group called “The Association” that felt “confident it could enlist 3,000 men of similar sentiments ‘within three miles of the Court House.’”[31] In the Spring of 1775, Atwood saw a paper in Kearsley’s hand containing many signatures that declared “all Englishmen should combine together to join the British Forces when they should arrive.”[32]

May we speculate that, after Paine arrived as an English émigré in November 1774, Kearsley viewed him as a potential Association member and fodder for his Loyalist plans? While inspecting Paine’s ship, had Kearsley read through notes by Paine and recognized his extraordinary written communication skills? As Paine regained strength, had Kearsley tried to proselytize him as an “Englishman” to join his group? Alternately, did he intend to approach Paine after recovery by playing on Paine’s gratitude for saving his life? Assuming this was why Kearsley cared for Paine is speculation, but reasonable speculation. This explanation gains traction by considering Kearsley’s activities in September and October 1775.

On September 5, 1775, Kearsley reportedly entered a bookstore and, handling a book titled Tryals for High Treason, asked “in a sneering insulting manner” whether “Mr. Adams” should peruse the book.[33] Presumably he referenced John Adams who was accused in July 1775 based on confiscated letters of seeking independence.[34]

On September 6 another Loyalist, Isaac Hunt, was hauled in a cart around the city and required, whenever the cart stopped, to renounce his Loyalist views to avoid being tarred and feathered.[35] With Hunt repeatedly complying, the situation would have fizzled out except that, when the cart and crowd stopped at the house of Kearsley—known as a notorious Loyalist—

the Doctor threw up the sash and pulled wide open the shutters, and taking up a pair of loaded pistols, cocked, presented and snapped one of them. The crowd then gave way, and one of the guard seeing the Doctor determined to take away some lives, advanced with a charged bayonet, and making a pass at his breast he wounded the Doctor in the left hand. Another of the guard advanced immediately, and the Doctor snapped a second pistol at him as he came up; he then seized the pistol, and the Doctor snapped it a second time against his breast, while in his hand. This second person, in attempting to wrest the pistol out of his hand, brought the Doctor down upon the pavement. He was instantly twisted into the cart with Mr. Hunt and the people gave a loud huzza, and the Doctor to show his contempt for the people, took his wig in his wounded hand and swinging it around his head huzzied louder and longer than the rest. . . . He was then carted to the Coffee-House, and thence round the city with a determined resolution to tar and feather him, if it could be done with safety to his life.[36]

As the cart ride proceeded, Kearsley was so offensive that the guards ultimately feared for his life, removed him from the cart, and returned him to his house.[37] Kearsley later sought to memorialize a fantastical version of those events by sending a sketch to London, to be made into an engraving, that showed him causing a crowd of 5,000 to flee because he fired a “Single pistol” and by contending bizarrely that he retained his pistols during the cart ride and periodically frightened the crowd by snapping them—that is, cocking them and pulling the triggers, even though they were not loaded.[38]

Alexander Graydon, though sympathetic to Kearsley and disgusted with how Kearsley was treated on September 6, nonetheless recognized that he was an “extremely zealous loyalist, and impetuous in his temper,” who, before September 6, “had given much umbrage to the whigs” and, Graydon understood, “been detected in some hostile machinations.”[39] Kearsley’s arrogant and self-centered personality was known to Graydon. While Kearsley and friends lived at a boarding house operated by Graydon’s mother, they set up a “howl” around Philadelphia and Kearsley—then in his forties—rode his horse up the boarding house staircase, frightening everyone there.[40]

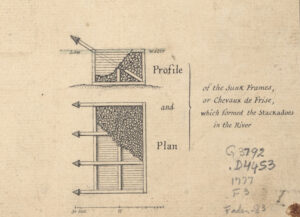

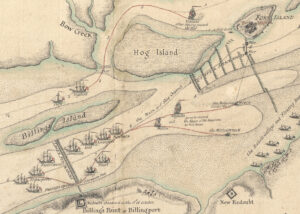

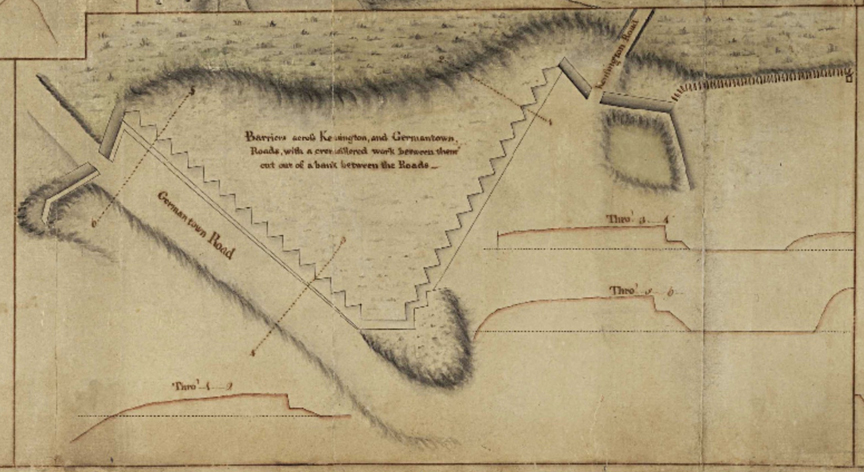

By contrast with the September 1775 events, Kearsley’s actions that October, to Pennsylvanians supporting the American cause, were stunningly treasonous. Kearsley sent a map to British authorities in London that disclosed precisely where British ships could maneuver around carefully constructed and critically important sharpened log structures sunk into the Delaware River—chevaux de frise—to reach and attack Philadelphia. The map was accompanied by a letter proposing that, if they sent troops, Kearsley would lead those troops and an equivalent number of Loyalists who, he promised, would then come forward. Kearsley and his co-conspirators were arrested after the papers were intercepted.[41]

Locations of those chevaux de frise—the prime defense protecting Philadelphia—were deeply held secrets.[42] Kearsley and his co-conspirators were charged “with practices inimical to the Liberties of America, and dangerous to the Peace and Safety of this Province” without any details, and certainly no reference to the confiscated map.[43] Perhaps the authorities were worried that efforts would be made to spring Kearsley from jail to obtain that information. Kearsley’s efforts to disclose the information were so well hidden that our knowledge of those efforts comes solely from a letter that Caesar Rodney sent to his brother.[44]

But keeping those details secret allowed a group of Loyalists to complain that the accusers of Kearsley and his co-conspirators had not “Published their Crimes” and to ridicule their accusers’ contention that the actions were “so bad that the Mob would tear them to Pieces” if specifics were disclosed.[45] That also allowed James Allen to assert that Kearsley’s “only crime is, thinking differently from” his “oppressors,” that he was “not charged with any overt act or intention,” and that his sole “offence was writing a passionate letter to England abusing the Americans long before the commencement of Independancy.”[46]

Informing the British how to attack Philadelphia by maneuvering around the sunken defenses in the Delaware River was glaringly different than “thinking differently.” Other Loyalists were hanged for far less egregious activities.[47]

Paine surely knew about Kearsley’s well publicized cart ride and later imprisonment but mentioned Kearsley only in his March 1775 letter to Franklin.[48] Kearsley never mentioned Paine but presumably read Paine’s Common Sense, Forester essays, and his first three Crisis essays published before Kearsley died in November 1777.[49] Imagine how Kearsley raged while reading Paine’s proclamation that “every Tory is a coward” and, “though he may be cruel, never can be brave.”[50] Or Paine’s claims that “the instant that” a Tory “endeavors to bring his toryism into practice, he becomes A TRAITOR” and that a “traitor is the foulest fiend on earth.”[51]

Did Kearsley realize that, had he not cared for Paine, independence may never have transpired?[52] As developments unfolded between Kearsley’s imprisonment in October 1775 and his death in November 1777, particularly if he recognized and dwelled on that irony, would execution shortly after arrest have seemed an attractive alternative? Rather than being hanged in October 1775, Kearsley watched helplessly for two years as his world turned upside down and the decision to bring Paine back from the brink gave birth to his nightmare.

[1] During the Seven Years War, Philadelphia, accessible through Delaware Bay, “found its shipping harassed” by French “privateers.” James G. Lydon, Pirates, Privateers, and Profits (Upper Saddle River, NJ: The Gregg Press, Inc., 1970), 133. During that war, Paine escaped apprenticeship by joining a English privateer that captured many prizes. Craig Nelson, Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations (New York: Viking, 2006), 28.

[2] Our knowledge of Paine’s 1774 voyage is confined to a letter he wrote to Franklin. Thomas Paine to Benjamin Franklin, March 4, 1775, The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, ed. P. Foner (New York: The Citadel Press, 1945), 2:1130-1131. “A Putrid Fever broke out among” those below decks with only five or less escaping “the disease” and a doctor on board prevented “as deplorable a Situation, as a Passage of nine Weeks could have rendered us.” Paine “suffered dreadfully with the fever” and “had very little hopes that the Capt. or” he “would live to see America. Dr. Kearsley of this Place, attended the Ship on her Arrival, and when he understood that” Paine had Franklin’s “Recommendation he provided a Lodging for” Paine “and sent two of his Men with a Chaise to bring” him “on Shore,” because Paine “could not at that Time turn in” his “bed without help” and “was six Weeks On Shore before” he “was well enough” and, by March 1775, was “perfectly recover’d.” Typhus fever, called “putrid fever,” was highly contagious. Russel M. Wilder, “The Problem of Transmission in Typhus Fever,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases (July 1911), 9:11; Emmanouil Angelakis, Yassina Bechah & Didier Raoult, “The History of Epidemic Typhus,” Microbiology Spectrum, August 30, 2016, Vol 4, Issue 4.

[3] Paine to Franklin, March 4, 1775, Complete Writings, 1130-1131. Dr. John Kearsley, Jr., was a nephew of Dr. John Kearsley, Sr., who died in 1772. William S. Middleton, “The John Kearsleys,” Annals of Medical History, 1921, 3:391-402. The uncle’s name is otherwise unmentioned with “Kearsley” referring solely to Dr. John Kearsley, Jr. Whitfield Bell, Jr., Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1999), 2:375.

[4] Paine to Franklin, March 4, 1775, Complete Writings, 1130-1131.

[5] E.g., Alfred O. Albridge, Man of Reason: The Life of Thomas Paine (New York: J. P. Lippincott, 1959), 29; Reneé Critcher Lyon, Foreign-Born American Patriots: Sixteen Volunteer Leaders in the Revolutionary War (Jefferson, NC: MacFarland and Co., Inc., 2014), 14; Alfred Marrin, Thomas Paine: Crusader for Liberty (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), 28-29; Frank Smith, Thomas Paine: Liberator (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1938), 11-12; W.E. Woodward, Tom Paine: America’s Godfather (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1945), 55-56.

[6] John Keane, Tom Paine: A Political Life (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1995), 84-85 (the cited source says merely that Paine “visited” relatives of the captain). See also David Powell, Tom Paine: The Greatest Exile (London: Hutchinson, 1985), 58 (creating imaginary dialogues between Paine and Kearsley).

[7] George Washington Corner, Two Centuries of Medicine: A History of the School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott, 1965), 2 & 31. Philadelphia had “about 30” practicing doctors by 1765 while the Medical School had from “one to seven” graduates each year from 1768 through 1773 and, in 1773, had “more than 30 students … attending lectures”; Whitfield J. Bell, Jr., The Colonial Physician & Other Essays (New York: Science History Publications, 1975), 6.

[8] Paine to Franklin, March 4, 1775, Complete Writings, 1130-1131, italics added.

[9] “An ACT to prevent infectious Diseases being brought into the Province,” The Acts of Assembly of the Province of Pennsylvania … (Philadelphia: Hall and Sellers, 1775), 505 (Art. III (Governor to appoint physicians whenever incoming ships are “disordered with any infectious disease”). Some biographers recognized that Paine meant what he said. David Freeman Hawke, Paine (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975), 25; Scott Liell, 46 Pages: Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to American Independence (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2003), 46-47; Robin McKown, Thomas Paine (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962), 26; Vikki J. Vickers, “My Pen and My Soul have ever Gone Together,” Thomas Paine and the American Revolution (New York: Routledge, 2006), 14; Bernard Vincent, Thomas Paine, ou La religion de la liberté, biographie (Paris: Aubier Montaigne, 1987), 41.

[10] No Paine biographer who identified Philadelphia locations apparently considered the effects of Pennsylvania law. Albridge, Man of Reason, 29; Calvin Blanchard, The Life of Thomas Paine (New York: Calvin Blanchard, 1850), 11; Richard Blunck, Thomas Paine (Berlin: Holle & Co., 1936), 17; T. Browne, An Impartial Sketch of the Life of Thomas Paine (London: T. Browne, 1792), 6; George Chalmers (“Francis Oldys”), The Life of Thomas Pain (London, John Stockdale, 1791), 39; James Cheetham, The Life of Thomas Paine (New York: Southwick & Pelsue, 1809), 31-32; Eric Foner, Tom Paine and Revolutionary America (London: Oxford University Press, 1976) 19; Jack Fruchtman, Jr., Thomas Paine: Apostle of Freedom (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1996), 4; Leo Gurko, Tom Paine: Freedom’s Apostle (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1957), 15; Hawke, Paine, 25; Harvey J. Kaye, Thomas Paine and the Promise of America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2006), 34; Keane, Tom Paine, 84-85; Liell, 46 Pages, 46-47; W. J. Linton, The Life of Paine (New York: Peter Eckler, 1892), 7; Lyon, Foreign-Born American Patriots, 14; Marrin, Thomas Paine, 28-29; McKown, Thomas Paine, 26-27; Powell, Tom Paine, 58; Ellery Sedgwick, Thomas Paine (Boston: Small, Maynard and Company, 1899), 11; W. T. Sherwin, Memoirs of the Life of Thomas Paine (London: R. Carlile, 1819), 22; Smith, Thomas Paine, 11-12; George Spater, “The Early Years, 1737-74,” Citizen of the World: Essays on Thomas Paine, Ian Dyck, ed. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988), 23; Vickers, “My Pen and My Soul have ever Gone Together,” 14; Audrey Williamson, Thomas Paine: His Life, Work and Times (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1973), 64; Vincent, Thomas Paine, 41; W.E. Woodward, Tom Paine, 55-56.

[11] “An ACT to prevent infectious Diseases being brought into the Province,” The Acts of Assembly of the Province of Pennsylvania, 505 (Art. I & III). After 1742, “a quarantine station was opened on Province Island” that was referenced on a 1753 map as a “Pest House.” Jim Green, Librarian, “Pandemic Reading: Quarantine and Isolation at the Lazaretto,” The Library Company of Philadelphia, librarycompany.org/2020/05/12/pandemic-reading-quarantine-and-isolation-at-the-lazaretto/. “Lazzaretto” is borrowed from the Italian name for “Pest House.” Jim Murphy, “Philadelphia’s Lazaretto,” Medium, southwarkhistory.org/philadelphias-lazaretto-00895c003845. See The Gentleman’s Magazine for August 1753 (London: E. Cave, 1753), map between 372 and 373.

[12] James Higgins, “Public Health,” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/public-health/.

[13] “An ACT to prevent infectious Diseases being brought into the Province.” The Philadelphia docks are seven nautical miles from Mud Island. “Delaware Bay,” U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Atlantic Coast: Sandy Hook, New Jersey to Cape Henry, Virginia (Washington: D. C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) & National Ocean Service, 2025), nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/publications/coast-pilot/files/cp3/CPB3_WEB.pdf, 58:224 (Nos. 274 & 277: Nautical Miles 79.5N to 86.5W). See “Fort Mifflin,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Mifflin (located on Mud Island). Pennsylvania law had, since 1700, generally prohibited disembarking from infected ships in Philadelphia. Karl Frederick Geiser, Ph.D., Redemptioners and Indentured Servants in the Colony and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (New Haven, CT: The Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Co., 1901), 53 & 60-68.

[14] Paine biographers assume his ship docked at, and Paine was taken to Kearsley, in Philadelphia. E.g., Marrin, Thomas Paine, 28; Aldridge, Man of Reason, 29; Liell, 46 Pages, 48; Nelson, Thomas Paine, 13-14 & 53; Woodward, Tom Paine, 56. Both actions were prohibited by Pennsylvania law. “An ACT to prevent infectious Diseases being brought into the Province,” 505 (Art. II & III). Nearly every Article imposed monetary penalties, which were often severe. “An ACT to prevent infectious Diseases being brought into the Province,” 505-508 (Art. II, III, IV, VI, VII, VIII, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV).

[15] “An ACT to prevent infectious Diseases being brought into the Province,” 505 (Art. IV). Vinegar was long used to cleanse infected ships in Philadelphia. Simon Finger, The Contagious City: The Politics of Public Health in Early Philadelphia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012), 37. See Randolph Shipley Klein, “Dr. John Kearsley, Jr.: The Mad Tory Doctor,” Transactions & Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 36:159 (Kearsley and vinegar); “Memorial of Mrs Kearsley,” Daniel Parker Cote, The Royal Commission on the Losses and Services of American Loyalists 1783 to 1785, Hugh Edward Egerton, ed. (Oxford, England: The Rorburghe Club, 1915), 355-356 (testimony of Captain Robert Davis that Kearsley “made and sold vinegar” and had a “vinegar factory”).

[16] John Kearsley, “Observations on the Angina Maligna, or the putrid and ulcerous sore throat, with a method of treating it,” The Scots Magazine (Edinburgh, Scotland), December, 1769, 31:626.

[17] Wilder, “The Problem of Transmission in Typhus Fever,” 9:19.

[18] Suzanne M. Shultz, “Epidemics in Colonial Philadelphia from 1699-1799 and The Risk of Dying – 2,” www.varsitytutors.com/earlyamerica/early-america-review/volume-11/early-american-epidemics-2 (“Untreated severe typhus may be fatal in nine to eighteen days” with symptoms including “delirium”).

[19] “An ACT to prevent infectious Diseases being brought into the Province,” 506-507 (Art. VI, IX, X & XII).

[20] “An ACT to prevent infectious Diseases being brought into the Province,” 506 (Art. VI).

[21] Paine’s resources, limited to 35 pounds in June 1774, were likely reduced or exhausted through purchase of a cabin ticket and interim living expenses before he left England. Hawke, Paine, 19-20 & 25; Foner, Tom Paine and Revolutionary America, 19; Nelson, Thomas Paine, 45.

[22] Paine to Franklin, March 4, 1775, Complete Writings, 2:1130-1131 (Lodging”).

[23] Harold E. Farmer, “An Account of the Earliest Colored Gentlemen in Medical Science in the United States,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, April 1940, 8:602-604. After obtaining his freedom from a subsequent owner, he became Dr. James Derham, the first trained Black physician in the United States. Carter Godwin Woodson, The Negro Professional Man and the Community, with Special Emphasis on the Physician and the Lawyer (Washington, D.C.: The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc., 1934).

[24] Bell, The Colonial Physician & Other Essays, 19-20. In 1774, eight doctors including Kearsley were selected to inoculate poor residents against smallpox without charge. Bell, Patriot-Improvers, 2:376. But caring for a typhus patient for multiple weeks, particularly if that required travel and absorbing other charges, was a significantly different commitment.

[25] Christ Church Hospital: Extracts from the Will, and Codicil Thereto, of the Founder, Dr. John Kearsley (Philadelphia: T. K. and P. G. Collins, 1850), 3-9.

[26] Deborah Mathias Gough, Christ Church, Philadelphia: The Nation’s Church in a Changing City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), 193. See George B. Roberts, “Christ Church Hospital,” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church (March, 1976), 45:90-91 (after his uncle died, Kearsley promptly sought “to get more money from his uncle’s estate,” most of which was left to establish an Infirmary for poor women, and sued after his demands were rejected). Searching the original vestry minutes of Christ Church for “Kearsley” conveys how disruptive the challenge was to the uncle’s intent to establish that facility. “Vestry minutes, Christ Church and St. Peter’s Church, v. 2, 1761-1784,” Christ Church in Philadelphia, www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-book.cfm/ChristChurch.MinuteBooks_v2?ft=F04638CF-155D-01E7-005BA1AA6D0DCEBA&q=wall. The uncle’s intent was realized only because of donations from others. Gough, Christ Church, Philadelphia, 193.

[27] Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Leonard W. Larabee ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1963), 110, n9.

[28] Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 110, n9. Paine’s statement that Franklin’s letter motivated Kearsley is not determinative. Paine to Franklin, March 4, 1775, Complete Writings, 2:1130-1131. Whether Paine’s assumption resulted from Kearsley referencing the letter or not, Kearsley’s animosity, of which Paine was presumably unaware, negates the assumption.

[29] Kearsley’s opponents declared that he was “known to every one to be a violent enemy to the Cause.” “To the Printers of the Pennsylvania Journal,” Pennsylvania Journal; and The Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), September 20, 1775, 1 & 4. A witness supporting a compensation claim made by Kearsley’s widow to a British commission similarly testified that Kearsley was “a violent Loyalist” and “one of the most zealous that he ever knew.” “Memorial of Mrs Kearsley,” Cote, The Royal Commission on the Losses and Services of American Loyalists 1783 to 1785, 355-356 (testimony of Samuel Shoemaker).

[30] “Papers Relating to the War of the Revolution, 1775-1777,” Pennsylvania Archives, Second Series, ed., John B. Linn & Wm H. Egle, M.D. (Harrisburg, PA: Lane S. Hart, State Printer, 1879), 1:611. Kearsley belonged to the Society of the Sons of St. George, founded to provide advice and assistance to “Englishmen in Distress.” Theodore C. Knauff, A History of the Society of the Sons of Saint George (Philadelphia: Sons of St. George, 1923), 15-17. Kearsley may have viewed that Society as another avenue for achieving his Loyalist goals. “Papers Relating to the War of the Revolution, 1775-1777,” 1:611.

[31] Elwood C. Parry, Jr., “Traitors by Choice or Chance,” Bulletin of the Historical 5ociety, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Fall 1968, 16:167.

[32] “Papers Relating to the War of the Revolution, 1775-1777,” 1:611.

[33] Klein, “Dr. John Kearsley, Jr.: The Mad Tory Doctor,” 36:161.

[34] John T. Morse, Jr., John Adams (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1893), 102-103.

[35] “To the Printers of the Pennsylvania Journal,” September 20, 1775, 1 & 4.

[36] Ibid. A September 6, 1775 diary entry by Christopher Marshall is often cited as a reliable version. Passages from the Diary of Christopher Marshall, William Duane ed. (Philadelphia: Hazard & Mitchell, 1839-1849), 1:46-47.

[37] “To the Printers of the Pennsylvania Journal,” September 20, 1775, 1 & 4.

[38] Caesar Rodney to Thomas Rodney, October 9, 1775, Letters of Delegates of Congress 1774 to 1789, Paul H. Smith, ed. (Washington, D. C. Library of Congress, 1977), 2:152 (relating Kearsley’s sketch). Kearsley’s fantasy sketch was contrary to contemporary accounts. E.g., Henry Belcher, The First American Civil War, First Period, 1775-1778 (London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1911) 2:256 (relating version by a “witness”); Elizabeth Drinker, Extracts from the Journal of Elizabeth Drinker, Henry D. Biddle ed. (Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott, 1889), 40 (September 6, 1775, diary entry); Alexander Graydon, Memoirs of a Life, chiefly passed in Pennsylvania, within the Last Sixty Years (Harrisburgh, PA: John Wyeth, 1811), 111 (Graydon was a witness at the Coffee House). Though second-hand, the most compelling counter to Kearsley’s version may be the account that Isaac Hunt related to his son. Leigh Hunt, The Autobiography of Leigh Hunt, Roger Ingpen, ed. (Westminster, England: Archibald, Constable & Co, Ltd., 1903), 7-8.

[39] Graydon, Memoirs of a Life, 111.

[40] Bell, Patriot-Improvers, 2:375 (Kearsley born in 1724); Graydon, Memoirs of a Life, 63-64 (boarding house purchased in 1764 or 1765) and 67 (Kearsley and staircase).

[41] Caesar Rodney to Thomas Rodney, October 9, 1775, Letters of Delegates of Congress 1774 to 1789, Paul H. Smith, ed. (Washington, D. C. Library of Congress, 1977), 2:152.

[42] Robert B. Roberts, Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1988), 505-506; “Minutes of the Council of Safety of the Province of Pennsylvania,” Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania … (Harrisburg: Theo Fenn, 1858), 10:362-363 (emphasizing importance of keeping locations secret by naming trusted pilots who would know the locations).

[43] “Minutes of the Council of Safety of the Province of Pennsylvania,” 10:359. Newspaper reports were similarly conclusory and vague. Pennsylvania Journal; and The Weekly Advertiser, October 11, 1775, 3 (“a scene of villainy was opened” by examining confiscated papers); Pennsylvania Journal; and The Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), October 18, 1775, 3 (unspecified “high crimes against this country”).

[44] Caesar Rodney to Thomas Rodney, October 9, 1775, 2:152.

[45] “Papers Relating to the War of the Revolution, 1775-1777,” 1:561-562.

[46] James Allen, Diary of James Allen, Esq., of Philadelphia, Counsellor-at-Law, 1770-1778, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, January 1886, 9:433.

[47] Wallace Brown, The Good Americans: The Loyalists in the American Revolution (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1969), 138-139 (in Pennsylvania, John Roberts was hanged for aiding “the British occupying forces in Philadelphia” and, in Connecticut, Moses Dunbar was “hanged for accepting a British commission and recruiting troops”).

[48] Paine was a Philadelphia editor during most of 1775. Hawke, Paine, 28. He undoubtedly consumed 1775 newspaper reports about Kearsley. “To the Printers of the Pennsylvania Journal,” Pennsylvania Journal; and The Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), September 20, 1775, 1 & 4; “Philadelphia Committee Chamber,” The Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), September 27, 1775, 4; Pennsylvania Journal; and The Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), October 11, 1775, 3; Pennsylvania Journal; and The Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), October 18, 1775, 3; The Pennsylvania Evening Post (Philadelphia), October 24, 1775, 3; Pennsylvania Journal; and The Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), October 25, 1775, 3; The Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), October 25, 1775, 3. See also “Philadelphia, Nov. 22,” The Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), November 22, 1775, 3.

[49] Thomas Paine, Common Sense, Complete Writings, 1:3-49; Thomas Paine, “The Forester’s Letters,” Complete Writings, 2:60-87; Thomas Paine, “Crisis No. 1,” Complete Writings, 1:50-57 (December 19, 1777); “Crisis No. 2,” Complete Writings, 1:58-72 (January 13, 1777); “Crisis No. 3,” Complete Writings, 1:74-101 (April 19, 1777); “Crisis No. 4,” Complete Writings, 1:102-105 (September 12, 1777).

[50] Common Sense, Complete Writings, 1:53.

[51] “Crisis No. 3,” Complete Writings, 1:77 (“TRAITOR”; “Crisis No. 2,” Complete Writings, 1:62 (“foulest fiend”).

[52] Common Sense transformed the term “independence” amongst American leaders from a third rail into a rallying cry. E.g., Morse, John Adams, 102-103; Robert A. Ferguson, “The Commonalities of Common Sense,” William & Mary Quarterly 57 No. 3 (July, 2000), 465.

One thought on “The Loyalist Who Gave Birth to His Nightmare”

Kearsly’s wife and children suffered tribulations of their own after his death. Moving to England in 1778, their ship was dashed on the rocky Cornwall coast in stormy seas. Newspapers carried this account:

“Extract of a Letter from Plymouth, Dec. 9.

“During the last Fortnight we have had very severe Weather here, to the Westward of us, by which a Snow Transport, from New-York, was wrecked near Marazion in Cornwall; amongst the Passengers saved were the Widow and Orphans of the late Dr. Kearsly, of Philadelphia, who suffered Death for persevering in his Loyalty to Great-Britain. The Widow and Children were brought on Shore almost naked; but, by the Humanity of the People, they were all cloathed, and a Collection was made for them, as they had lost all their Property, to the Amount of 50l. and a worthy Clergyman has taken two of his Children under his Care, to provide for them.”

[Northampton Mercury, 28 Dec 1778]