About an hour’s drive west from Raleigh, in North Carolina’s Moore County, the traffic thins out, the roads narrow, and the suburban sprawl of the Triangle area softens into farmland, ringed by trees, unrolling across the horizon.

While only a little over fifty miles from one of the country’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas, this is still the backcountry, and has been for centuries. On a sweltering day in late June 2025, it’s not hard to imagine a similar morning in July 1781, when the warm work of musketry crackled through the torpid Carolina air, centered around what, at the time, was the grandest home in these parts, a manse that went by a poetic moniker: the House in the Horseshoe.

“It’s rural today, and it was even more so in the eighteenth century,” says Amanda Brantley, the site supervisor for what is now a state historic house museum. “There weren’t a lot of neighbors.”

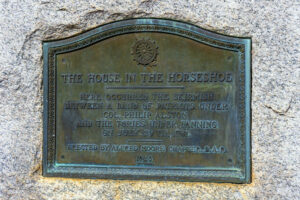

Located in the North Carolina Piedmont region, on a distinctively shaped bend of the nearby Deep River (hence, the name), the two-story framed structure with a gable roof was the site of a small battle, one of many skirmishes that rumbled back and forth across the Carolina backcountry in the final years of the Revolution. The fighting here was unlike the major engagements farther north or even the series of battles between Gen. Nathanael Greene and Gen. Charles Cornwallis in other parts of the Carolinas. These backcountry dustups were not set-piece battles between Continental soldiers in blue and buff and British redcoats marching in tight formations. “Here in North Carolina, the vast majority of the backcountry fighting is between Loyalist militia and Patriot militia,” says Katie Hatton, a historian and editor with the North Carolina Office of Archives and History. “Many of those on both sides were from families that had already been here for generations.” These men and their kin knew each other, and there were often grudges and old feuds that needed to be settled. “In many cases it was like a civil war,” says Hatton.

This fight was one of over thirty-five skirmishes fought in the the backcountry of both North and South Carolina from early 1781 until late 1782. “The House in the Horseshoe is one of the more notable ones in that we still have the visual marker,” Hatton said. The sites of many other small engagements, fought at nameless creek crossings or in anonymous patches of swamp, have been lost.

The other reason the fight at the house was notable had to do with the opposing commanders: two colorful, controversial figures—one a Patriot, one a Loyalist. Both of them were stone killers. Both of them, at various points in their lives, were outlaws. Both seemed motivated less by king or country than by the possibilities for revenge and personal gain.

Philip Alston, the ne’er-do-well son of a prosperous plantation owner, built the house in 1772 after purchasing a large plot of land on either side of the bend of the river. By 1777, Alston’s property included 6,936 acres, and he was a full colonel in the local militia—a position he had lobbied for. But Alston wasn’t just fighting against the king; he was also battling political enemies—one of whom he was later accused of murdering.[1]

In the summer of 1781, Alston and his men were in pursuit of a notorious Loyalist commander. They’d caught up with him and possibly killed one of his officers, but most of the enemy force escaped.

On the morning of July 29, while Alston and his men were camped at his homestead, that notorious Loyalist commander—Col. David Fanning—returned. He and his men had quietly slipped back into what was then Cumberland County, and now they were on the attack.

Abused as a child, Fanning had become an Indian trader in North Carolina, and he made friends with the local Cherokee and Catawba peoples. He would later claim that at the outbreak of the war, he had been sympathetic to the grievances of his fellow Americans—that is, until he was beaten and robbed by a group of Patriot thugs. Fighting for the crown, he proved to be a wily and audacious commander, known for his bold tactics, ruthlessness, and an uncanny ability to escape captivity (no less than fourteen times, according to some accounts). Disfigurement from a childhood skin disease that left open sores and blotches on his head and face only added to his terrifying reputation.[2]

Fanning knew that Alston had divided his force as they headed back from their unsuccessful mission against him. With a small advantage in numbers and the element of surprise, he decided to turn the tables on his pursuers. He also had motive: During their earlier skirmishes, he suggested in his memoir, the officer that Alston’s men had killed was murdered in cold blood.

At daybreak, Fanning launched his assault. His force, approximately thirty strong, came from the north, across what was then open farmland but today is covered with trees. Alston had about twenty-five men, who immediately barricaded themselves in the house, as his wife, Temperance, hid their four youngest children in the fireplace that still stands in the center of the great room.

In his memoir, written decades later, Fanning described the action and his motivation:

As the day dawned, we advanced in three divisions, up to a house, they had thrown themselves into. On our approach, we fired upon the house, as I was determined to make examples of them, for behaving in the manner they had done.[3]

The house still bears the scars of that ensuing three-hour skirmish. “We have over thirty bullet holes in the walls,” says Brantley, gesturing to a cluster around the house’s west door. There are also bullet holes in the house. A recent ballistics analysis found that some of these shots were fired inside the house, suggesting the chaos of battle. “It was occasional volleys of fire, a lot of yelling and people running around,” she said. “They fought from both floors of the house.”

The climactic point in the battle came when the Loyalists tried to burn the house. Decades later, in his pension memorial, one of Alston’s men, Elijah Fooshee, recalled what happened. “One of the Tories (a Scotchman) during the battle got a bundle of flax & run with it after setting it on fire to burn the house, but being discovered by our party was shot down & when examined had three balls in him.”[4]

At some point, another incendiary attempt was made: This time, a group of Fanning’s men rolled a cart filled with burning straw into the side of the house, hoping to ignite it (a scene that is gleefully re-enacted to this day at the house’s annual Battle Day event).

After fighting that resulted in casualties on both sides (Fanning claims to have killed four of the rebels, while losing two of his men), Alston surrendered. Exactly what prompted that concession—and why it was not the Patriot’s commander himself who negotiated the terms—is still open to debate. Brantley thinks that it was the intercession of Temperance, fearing for the safety of her children, who rose to the occasion. “I call it her `Mom Moment,’” she says. “It’s 1781, the war has been going on for years, and now it has come to her doorstep, and she’s simply had enough.”

What happened next must have been an extraordinary sight.

The front door of the house opened, and out stepped the lady of the house, waving a piece of white linen. Firing on both sides ceased immediately. The men, Loyalist and Patriot alike, must have been stunned at this extraordinary act of courage. “Just to have the guts to open that door,” Brantley said, “she must have had a lot of gumption.”

In his memoir, Fanning wrote that “Col. Alstine’s lady” was “begin” for mercy. “On her solicitation, I concluded to grant her request,” he added haughtily.

At the house museum, Temperance’s words to Fanning are remembered differently—and recited differently, in the annual re-enactment of the scene.“We will surrender, sir,” she says, bravely, “on condition that no one shall be injured; otherwise we will make the best defense we can and if need be, sell our lives as dearly as possible.”

Whatever the truth about the tone of their parley, Temperance Alston and the Loyalist commander—he no doubt sporting the distinctive silk skullcap he wore to cover his scars and sores— then cobbled together a surrender document that Alston signed. It read:

I do hereby acknowledge myself a prisoner of War, upon my Parole to his Excellency Sir Henry Clinton, and that I am hereby engaged till I shall be exchanged or otherwise Released . . . I shall not in the mean time do or Cause any thing to be done prejuditial to the success of his Majesties arms or have Intercourse or hold Correspondence with the enemies of his Majesty.[5]

Lingering questions remain. Was Temperance acting as her husband’s mouthpiece—or did she compel Alston to surrender? If so, was he too afraid or ashamed to walk out that door and face his enemy as she had?

Regardless, the terms were quickly ignored: Alston went on to do a number of things “prejuditial” to both the king and his arms, not to mention any number of Moore County elected officials. Not long after he signed his pledge of neutrality, he was back fighting with the rebels. During a skirmish in Georgia, he was captured again by Loyalists. After the war, he became a state senator, but allegations shadowed him. Directed by the Moore County clerk of court George Glascock, a number of charges—from murder to his alleged disbelief in God—were levied against the colonel.

Hounded by Glascock, the volatile Alston struck back. In 1787, he hosted a public dinner party at the House in the Horseshoe. Many were invited, and Alston made sure to make himself visible to all in attendance. That night, while the party was in full swing, Glascock was murdered. The alleged killer was an enslaved man of Alston’s named Dave. The furor over the murder of a court official eventually forced Alston to flee the house. (It was later bought by Benjamin Williams, governor of North Carolina, who was also a colonel under George Washington and fought at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse.)

As for Alston, he was captured and jailed in Wilmington and later escaped to Georgia, where, in 1791, he was shot to death through his bedroom window. Some say the man who pulled the trigger was the same enslaved man, Dave, that Alston had compelled to kill Glascock.[6]

As for Fanning, after the fight at the House in the Horseshoe, he continued his effective raids—including a bold attack on the wartime North Carolina capitol of Hillsborough, where he kidnapped the governor of the state. After the war, he was just one of three Loyalist North Carolinians exempted from a statewide pardon of those who had fought for the crown. Vilified as a traitor and a butcher, not to mention a disfigured monster, Fanning fled to Canada. After successfully dodging a charge of raping a fifteen-year-old girl in New Brunswick, he moved to Nova Scotia, where he became a successful shipbuilder. He died there, aged seventy, in 1825.[7]

Two volatile, violent men.

One brave woman.

An obscure engagement that nonetheless illuminates some of the desperate realities of the backcountry war.

That was the battle at the House in the Horseshoe—a house that still stands, and still keeps its secrets.

Visit the House in the Horseshoe

The House in the Horseshoe, a North Carolina state historic site, is open Tuesday–Saturday, 9 a.m.–5 p.m. It is closed on Sunday, Monday, and most major holidays. Admission is free, and guided tours are offered. Consult the website for more information: historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/house-horseshoe.

288 Alston House Rd.

Sanford, N.C. 27330

[1] Jessica Lee Thompson, “Philip Alston,” North Carolina History Project, 2025, northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/philip-alston/.

[2] North Carolina History Project, “David Fanning (1755–1825),” North Carolina History Project, 2025, northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/david-fanning-1755-1825/. Harry Schenawolf, “Loyalist David Fanning: Fierce, Ruthless Southern Partisan,” Revolutionary War Journal, October 16, 2022, revolutionarywarjournal.com/houdini-of-the-american-revolution-loyalist-col-david-fanning-fierce-and-most-feared-warrior-of-the-south/.

[3] David Fanning, The Narrative of Colonel David Fanning, (A Tory in the Revolutionary War with Great Britain;) Giving an Account of His Adventures in North Carolina, From 1775 to 1783. With an Introduction and Explanatory Note (New York: Joseph Sabin, 1865).

[4] Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters: Pension application of Elijah Fooshee R3635 f18NC, transcribed by Will Graves, revwarapps.org/r3635.pdf.

[5] North Carolina Historic Sites, “Surrender Terms and David Fanning: The Parole Written by David Fanning, Signed by Philip Alston,” 1781, historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/house-horseshoe/history/surrender-terms-and-david-fanning.

[6] Claiborne T. Smith, Jr., “Alston, Philip,” Ncpedia, State Library of NC, November 2022, www.ncpedia.org/biography/alston-philip.

[7] North Carolina History Project, “David Fanning (1755–1825).” Schenawolf, “Loyalist David Fanning: Fierce, Ruthless Southern Partisan.”

One thought on “Shootout at the House in the Horseshoe”

From 1778 to 1782 the war in the south was in fact a civil war in a rebellion. There were far more than the 35 skirmishes noted and, in fact, there were several hundred skirmishes and battles in the South where there was not a British Soldier present. It was murder, counter murder, feuds and old grudges settled.