Nowhere in the struggle that was the American Revolution was outside assistance more significant than at the siege of Yorktown during the autumn of 1781.[1] The French provided significant support from land troops, but it was the French Navy that really clinched the affair with their naval blockade that ultimately trapped the British army of Gen. Charles Cornwallis. However, there was another ally, not an ally of the United States (at least not officially) but an ally of France whose assistance was critical to enabling this naval entrapment to take place. That ally was Spain.

Spain provided significant illicit support during the war in terms of troops and supplies, all the while never being a declared ally of the United States (though it eventually declared war on Great Britain). In fact, several of its high-ranking diplomats and politicians were against American independence, likely due to the concern of an independence contagion spreading to Spain’s colonial holdings. What they did want, however, and sometimes working through the Americans was the way to do it, was to disrupt the international commerce and influence of their enemy, Great Britain. There were several ways that Spain, working both independently and with the French, accomplished this. The combination of the French and Spanish navies was enhanced to outnumber the vaunted British navy, thus posing a very real threat of an invasion of Great Britian itself. Although it was never conducted, this poorly kept secret presented enough of a threat to the British that they had to hold some of their navy back to protect the homeland. This diluted their effectiveness elsewhere around the world and curtailed their naval actions in the Americas.

Spain also had some positive goals of its own, most prominently to obtain Gibraltar and Minorca, though it ultimately secured only the latter. Finally, working with France in some cases, and in other cases on their own, they sought gains in the Caribbean, West Indies, and the Gulf coast. Most prominent here was the plan, after Yorktown was completed, to take Jamaica from the British (though it also never happened). As such, Spain had numerous targets, and if by helping the Americans they could get closer to those, the Americans were happy take that aid.

What they did to support the Yorktown operation is one of the forgotten and under-credited stories of the American Revolution. In fact, some have argued that Spain was the linchpin to winning (or at least winning more quickly) the war. How did this happen? Spain sent no ships to help the French. Nor did it send troops. Let us look at how they did help, first by going back to earlier in 1781.

One of the key French figures in the Yorktown affair was François Joseph Paul de Grasse, Marquis de Grasse-Tilly, familiarly known as Comte de Grasse. In 1781, de Grasse was dispatched to protect French interests in the Caribbean, working with Spanish forces in skirmishing with the British over various islands and territories along the Gulf coast of North America. In June 1781, de Grasse moved north to Cap Français, Saint-Domingue. Before arriving in the Caribbean, he had written to French officials that they could correspond with him through Saint-Domingue, if they wished, and that he might be available for operations in North America in the late summer.[2]

On July 12 the French ship Concorde, after making a rapid twenty-two-day journey from Newport, Rhode Island, arrived with letters for de Grasse from the French command, seeking his assistance, as well as with American pilots knowledgeable of the North American coastline to help him navigate the trip to deliver the assistance requested of him. There were three letters from General Rochambeau, one discussing where in North America de Grasse would come (recommending the Chesapeake), one stating the need for money (specifically at least 1.2 million livres), and the last on the state of the American army’s strategic situation (bleak, but with a glimmer of opportunity in Yorktown).[3] How would he respond to each of these?

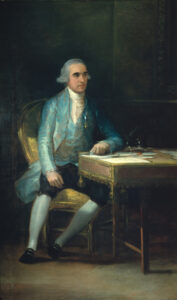

This is where Spain entered the picture, in the form of thirty-four-year-old diplomat Francisco de Saavedra de Sangronis (1746–1819). Saavedra’s deeds received little recognition at the time, probably written out of history due to Spain not having a treaty of cooperation with the Americans. He kept a detailed journal of his activities which surfaced due to the work of Spanish historian Francisco Morales Padron (1924-2010). In looking to shed more light on Spain’s involvement in the Revolution, Padron recovered the journal from the Spanish archives. He saw to the publishing of Journal of Don Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, 1780–1783 first in English in 1989 and subsequently in Spanish in 2004.

A former army officer turned diplomat; Saavedra was the consummate fixer.[4] And his handyman skills certainly came into play. Designated King Carlos III’s envoy in Havana, Cuba, Saavedra set sail from La Coruña, Spain in mid-1780. A British warship captured his ship, at which time Saavedra threw all his papers overboard. He was taken prisoner to Jamaica where he remained until his release in early 1781. The British never realized the importance of their Spanish prisoner. The king’s emissary and military strategist was allowed to leave Jamaica and travel via Trinidad to Havana.[5] The British intercepted his ship and diverted it to Jamaica. Saavedra presented himself to his captors as a merchant, arranged for an exchange, and left the island aboard a French ship in January 1781 bound for Havana. Saavedra was sent to Cap Français to work with de Grasse in establishing a plan for the two European allies to follow for the year.

De Grasse’s fleet arrived in Cap Français on June 16. The next day, Saavedra met with the French officer on board his ship, Le Ville de Paris.[6] Providing de Grasse with an adequate number of ships was the first issue with which Saavedra wrestled. France had commitments to leave at least four ships of the line with the Spanish forces in the Caribbean to protect French and Spanish possessions there. Without those ships, de Grasse might be heading to the Yorktown engagement shorthanded, in a situation where every ship counted. According to Saavedra, de Grasse “suggested to me that, in order not to diminish the force of his fleet without leaving the French Cape unprotected, four Spanish ships of the line could accompany him in the said enterprise.”[7] Saavedra raised objections to this, noting that as Spain was not officially an ally of the Americans, it would have negative consequences should it send ships of its own. He had a different proposal, a simple swap. If de Grasse took “all of his ships of the line, leaving for the present only some frigates, four Spanish ships of the line would go there [Cap Français] from Havana to protect the commerce of the colony.”[8] In essence, the Spanish navy would protect French-held possessions in the Caribbean in de Grasse’s absence.[9]

This numerical advantage was one reason de Grasse was able to overpower the British at the Chesapeake, as British Admiral Rodney didn’t think de Grasse would leave his West Indies possessions undefended and would hold back some ships. Others thought he might only send his copper-bottomed vessels, which comprised twelve of the twenty-eight he possessed. British military historian John Fortescue has noted that

the immediate cause of the disaster was, of course, the arrival of deGrasse in such immense strength. No one dreamed that he would carry all his ships with him to America. Rodney reckoned that he would take at most ten and supposed that by sending fourteen ships with [British Admiral Sir Samuel] Hood, and ordering six more, which for some reason never came, from Jamaica, he had made ample provision for all contingencies.[10]

One problem solved, but a much bigger obstacle still had to be surmounted: how to fund both de Grasse’s expedition and the ground forces in America, the latter woefully short of hard currency. According to Saavedra, de Grasse first tried to raise the cash at Cap Français. He “put printed notices on the street corners, inviting all who are willing to supply their money to him in exchange for bills redeemable at the treasury of Paris and a profitable rate of interest. All these expedients produced negligible effect; the total sum that could be collected was 50,000 livres.”[11]

Ironically, it was on this day, July 29, that de Grasse sent a letter back to Rochambeau on the speedy Concorde, stating he was opting to arrive at the Chesapeake and would do so “as soon as possible”. Additionally, he would bring over three thousand soldiers, and 1.2 million livres. Despite the latter promise, he confided to Saavedra back in Saint-Domingue “that the lack of money was making it impossible for him to launch the expedition to the north and that consequently his fleet would remain idle in port, thus losing the opportune juncture for executing an operation apt to hasten and advantageous peace.”[12] Clearly there was pressure from all quarters to find the funding, which was needed to pay American and French troops (including 3,000 being brought in by deGrasse) descending on Yorktown.

De Grasse and Saavedra were forced to hatch a different, riskier scheme. While de Grasse would “go with all his fleet by way of the Old Channel, even though the season was already dangerous, he would send ahead a swift frigate, on which I [Saavedra] could go if I wished [he did]; the frigate would bring from Havana the money that Spaniards there could contribute to him and would then go to await his fleet off Matanzas, whence all would set a course for the Bahama channel.”[13] The Old Channel extended 140 miles along Cuba’s northeast coast, a narrow curving passage between Cuba to the South and the Bahamas to the north. In the sixteenth century it had been used by the Spanish treasure fleet but had long since fallen out of favour due to the dangers posed by the many coral reefs and sandbars. This especially held true during hurricane season, exactly when de Grasse decided to take his twenty-eight ships of the line through.[14] The advantage: it was unlikely that the British would detect their movements there.

What happened next grew into a legend promulgated by numerous historians, known as the “Silver of Havana.” It started with an anonymous pamphlet written after the war, by someone who could not have been an eyewitness to the fundraising in Havana. The story is that the French request for money received such an enthusiastic response in Havana that the ladies of the city offered their diamonds for the cause. Some have even embellished the legend further, with one zealous student writing that the ladies offered all their jewelry, not just diamonds, and the French accepted these gifts.[15] Over the years, the legend grew.

As is often the case with historical legends, the truth is much more mundane, and that is the case here, though the real story of how the money was raised is still worth recounting. After arriving in Havana in the frigate Aigrette, Saavedra immediately ran into a problem. “They informed me that there was no money in the treasury because the ships had gone out for Veracruz on June 26th had not returned, and that what had remained in the treasury had been sent to Spain with a fleet that went out on July 24th.”[16] That was the bad news. The good news was that there were Spanish ships due to arrive with more money than Saavedra needed to supply deGrasse, but it was now August 15, and they had not yet arrived. Time was running short to catch Grasse and supply him with the cash he needed.

The only thing Saavedra could do was to turn to the citizenry, making known the urgency of the cause, so that each man could give what he could.[17] An announcement was made to the citizens and two French officers were dispatched to follow up on the contributions based on the generous terms offered. What happened was a miracle that needed no historical enhancement. They collected the requisite 500,000 pesos (approximately 800,000 livres) in just six hours. The money was put aboard the frigate Aigrette, and at six o’clock in the evening she set sail. [18]

So, how was the money raised so fast? It was not from the ladies of Havana auctioning off their jewelry. Saavedra had recruited twenty-eight investors in the venture. With a ship with the riches on its way, it apparently was not a tough sell. The investors were promised prompt repayment in specie at principle plus 2 percent interest as soon as the treasury ships docked. Most of those who loaned money would be repaid out of the first funds coming.[19] A list of the names of all twenty-eight investors is still available today. Within six months, all were repaid.

On August 18, the Aigrette, loaded with six tons of gold and silver (from Havana and other sources) comprising the 1,200,000 livres needed to support Yorktown, met up with de Grasse’s fleet at Matanzas. The money was distributed throughout the fleet to ensure that the loss of one ship did not sink the entire treasure. [20] Saavedra remained south to make sure the promised Spanish men of war were sent to guard French Haiti. Now the question was whether everything had come together in time to trap the British.

We know the answer today, but it was not so certain at the time. A desperate Washington wrote a letter to Lafayette on September 2 expressing that he was “distressed beyond expression, to know what is become of the Count de Grasse” and as a result worried that the operation would fail.[21] Unknown to him, Lafayette penned a letter the day before indicating that “I am Happy to inform Your Excellency that Count de Grasse’s Fleet is lastly arrived in this Bay … Previous to their Arrival Such positions Had Been taken By our Army as to prevent the Enemy’s Retreating towards Carolina.”[22] By August 30, de Grasse was indeed at the Chesapeake.

According to his journal, Saavedra received the news of de Grasse’s success at Yorktown on October 3. On that day, he recorded in his journal that de Grasse

had disembarked three thousand regulars there; that he had closed the mouth of the James river with three warships; that Cornwallis, whose retreat was cut off by this expedient was blockaded by the Marquis de Lafayette, that Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau with a considerable body of troops were marching many miles a day towards the same destination; and that it was believed that Cornwallis would find himself compelled to surrender.[23]

De Grasse defeated the British in the Battle of the Capes on September 5. His notification to Rochambeau on his victory over the Royal Navy arrived in Williamsburg on September 14, to the joy of Rochambeau and Washington who arrived the same day. The rest, as is said, is history.

In the end, Saavedra’s understanding of de Grasse’s situation permitted the admiral to move with great speed and overwhelming strength. By promising to cover Cap Français with the Spanish squadron, Saavedra made it possible for de Grasse to take his entire fleet. The money collected in Havana was the greatest accomplishment. De Grasse would later remark that “the silver pesos donated by the people of Havana were the bottom dollars,” the financial bedrock on which US independence was built.[24] Comte de Vergennes, the French Foreign Minister, in a letter of October 3, 1781, singled out Saavedra, “who . . . could not have contributed more amenity, goodwill and disposition for conciliation in the drafting of the plan of operations.”[25]

The inscriptions on the base on the Yorktown Victory Monument — a high marble column erected at the battlefield on the centennial of the victory, topped by an image of Liberty herself — celebrate the actions of Washington, Rochambeau, and de Grasse. They do not mention Saavedra or Havana’s contribution. Historians can only speculate as to what would have been the outcome had de Grasse left Saint-Domingue with a smaller fleet, spent several weeks in Cuban waters awaiting the cash he needed, or finally reached the Chesapeake to face a superior British squadron. That these circumstances never occurred can be attributed to Francisco de Saavedra.[26]

[1] James A. Lewis, “Las Damas de la Havana, el Precursor, and Francisco de Saavedra: A Note on Spanish Participation in the Battle of Yorktown,” The Americas, Vol. 37, No. 1 (July 1980), 83.

[2] Ibid., 85

[3] Charles Lee Lewis, Admiral de Grasse and American Independence (United States Naval Institute Press, 2014), 115-117.

[4] Nathaniel Philbrick, In the Hurricane’s Eye – The Genius of George Washington and the Victory at Yorktown (Viking, 2018), 132.

[5] Thomas Chavez, Spain and the Independence of the United States – An Intrinsic Gift (University of New Mexico Press, 2002), 183.

[6] Ibid., 200.

[7] Don Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, Journal of Don Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, translated by Aileen Moore Topping (University of Florida Press, 1989), 202.

[8] Ibid., 202.

[9] Chavez, Spain and the Independence of the United States, 201.

[10] J.W Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Volume III (MacMillian and Co. LTD., 1902), 395.

[11] Saavedra de Sangronis, Journal, 207.

[12] Ibid., 208.

[13] Saavedra de Sangronis, Journal, 209.

[14] Philbrick, In the Hurricane’s Eye, 149.

[15] Lewis, “Las Damas de la Havana,” 86.

[16] Saavedra de Sangronis, Journal, 211.

[17] Ibid., 211.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Lewis, “Las Damas de la Havana,” 95

[20] Philbrick, In the Hurricane’s Eye, 151.

[21] George Washington to the Marquis de Lafayette, September 2, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06865.

[22] Lafayette to Washington, September 1, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06851.

[23] Saavedra de Sangronis, Journal, 226.

[24] Chavez, Spain and the Independence of the United States, 203.

[25] Jonathan R. Dull, The French Navy and American Independence (Princeton University Press, 1975), 247.

[26] Lewis, “Las Damas de la Havana,” 98.

2 Comments

Richard, Your analysis is on the mark, Saavedra de Sangronis is definitely one of the heroes of the Yorktown Campaign. For those who have not read his diary, it is an important component in understanding the overall contributions of the Spanish government in supporting the American military without a formal acknowledgment of the American government. Saavedra pulled off a masterful piece of military diplomacy.

There is a fantastic new book just out now on Saavedra, that draws heavily from his diaries. His story is fascinating. What an accomplished man, and what an incredible role he played in the Revolutionary War. The book is: Francisco de Saavedra’s American Revolutionary War ~ The Spanish Contribution to the Battle of Yorktown. Great scholarship, riveting reading. The book immerses you in the behind the scenes machinations of the Spanish and the French to bolster the rebel colonies in their revolution against Britain. High level intrigue and action. Highly recommended.