On April 17, 1783, a dispatch arrived at Fort Rensselaer along the western bank of the Mohawk River, around two miles northwest of modern Canajoharie, New York. The messenger carried directions from Gen. George Washington to send “an Officer To the British Garrison at Oswago To announce a Cessation of Hostilities on the frontiers of New York.”[1] Maj. Andrew Fink, who served as the fort’s commanding officer, selected the twenty-four-year-old Capt. Alexander Thompson to carry the news around 120 miles west, across contested territory, to the British fort on Lake Ontario. Upon returning, Thompson detailed his difficult journey in a military report that now resides at the Library of the Society of the Cincinnati at the Anderson House in Washington, D.C.

The beginnings of the American Revolution have long captured the imaginations of Americans much more so than the concluding days described in Thompson’s journal. On April 19, 2025, tens of thousands of enthusiasts, locals and tourists alike, converged on the towns of Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts to commemorate the 250th anniversary of what, in 1837, Ralph Waldo Emmerson dubbed, “the shot heard round the world,” enjoying reenactments, parades, a rededication of Lexington’s Battle Green, and other festivities.[2] No doubt even grander, nationwide celebrations will take place in July 2026, when the country marks the semiquincenntial of independence. Hoping to seize on this excitement, local and state organizations across the country have planned a myriad of events to both mark anniversaries closer to home and carry the excitement well beyond the boundaries of what comprised the United States in 1776. Despite modern scholars’ best efforts to nuance this history, the groundswell of interest in the Revolution’s beginnings demonstrates the enduring appeal of the popular, albeit distorted, image of the plucky colonial farmer taking up arms against British tyranny. If the Bicentennial moment serves as any indicator, it is safe to assume that by the time the semiquincenntial of the war’s conclusion rolls around in 2033, there will be far less fanfare, at least in the United States.[3] Ironically, the architects of “Rev250” seem poised to learn what those who led the Revolution also found: rage militaire is difficult to sustain.

The account Thompson left of his mission to Lake Ontario, highlights the complexities that accompanied securing peace in Western New York. His description underscores the upheaval wrought by the Revolution in North America and the untold challenges that faced sundry peoples. During his trek along the Mohawk River, Thompson encountered a variety of people, and his descriptions underscore not only the fraught relationships in the region, but also the deep physical and emotional scars the violent war had left on both the land and its people. Many scholars have explored the alliance the British pursued with Native peoples during the Revolution; however, the pivotal role an unnamed chief of the Stockbridge people played in Thompson’s mission, especially in the crossing of Lake Oneida, demonstrates the equally critical place of indigenous alliance for American forces. Thompson’s account of the reaction of diverse peoples to Washington’s message reveals the surprise and outrage experienced by those fighting for—or at least in the name of—the crown in North America upon the war’s conclusion. Collectively, Thompson’s report reveals that for those who wish to truly understand the American Revolution, appreciating the myriad complexities and daunting challenges that surrounded making peace in 1783 is as important as grappling with its causes.

Alexander Thompson was born in New York City in 1759 to the merchant James Thompson and his wife, Margret Ramsay. He joined a militia unit commanded by Silvanus Seely in 1777 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in Col. John Lamb’s Regiment of Artillery in 1779. He fought in the Battles of Brandywine, Springfield and Yorktown. In early 1783, he was appointed commander of the artillery at Fort Rensselaer, Fort Plank, Fort Herkimer, and Fort Dayton in the Mohawk River Valley and traveled from Albany to Fort Rensselaer, which although largely lost to history, likely lay south of Otsquago Creek.[4]

A letter Thompson wrote to his brother shortly after his arrival captures his initial impression of the country. Thompson believed he was bound for a sparsely inhabited wilderness. “The idea I entertained of this country,” he explained, “was here & there at some very considerable distance, to find a little cleared land and a small log house to be destitute of all society & entirely confined to the walls of the Garrison.” Much to his surprise, his view from the fort—which was “situated on a height about half a mile from the river” and provided “a beautifull prospect of the country around, & shows you at one view as far as the eye will carry”—revealed “buildings and improvements you would little expect, to find in this supposed hidden country.” But the view also exposed the immense toll of war across the region. “All the settlements from Caughnawaga twenty miles below this place, untill yon get to old Fort Stanwix, Fifty miles above,” Thompson relayed, “are destroyed except a few houses which the inhabitants by their great exertions have secur’d with stockades.”[5]

Thompson had the opportunity to see this devastation firsthand shortly after his arrival, when he first traveled west to Lake Ontario. Since the surrender at Saratoga in October 1777, American forces stationed along the Mohawk River served largely as a defensive deterrent to the bands of Loyalist and their Native allies who often plundered the valley.[6] But in late 1782 a daring, and perhaps outrageous, plan was devised for a surprise winter attack on the British fort at Oswego led by the commanding officer in the region, Col. Marinus Willett. The genesis of the scheme is unclear. Willett’s son and biographer claimed George Washington had devised the plan, which a reluctant but dutiful Willett carried out, but a letter Washington sent to Gov. George Clinton in late July 1782, around the same time Willett’s son claimed Washington approached Willett with the plan, reveals Washington unwilling to spend more men or money on the region and perhaps a little frustrated with a pesky Willett.[7]

Regardless the plan’s origin, early on the morning of February 8, 1783, Thompson and, by his own estimates, 400 other men, including the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, known as “Onley’s Blacks,” set out along the Mohawk River and reached Lake Oneida on the evening of the 12th.[8] From there, the expedition progressed at breakneck speed. “For fear of being discovered we cross’d the same night on the Ice, which is about thirty miles over,” Thompson explained, “We left our sleighs at the lake and march’d along the Onieda river for Oswego. After we got below Oswego falls we took the Ice but were frequently Obliged to take the land for fear of being discovered by the enemies’ Indians that [were] out on hunting parties.” The men were within three miles of the fort before sunrise, when, according to Thompson, Willett followed the lead of, if Willett’s son’s account is to be believed, “a young Oneida Indian, called Captain John,” into the woods “with an intention he said of adva[ncing] on the works [on] the lake side.” Unfortunately for the men, the guide quickly became lost. “We were led . . . through the swamp to a considerable distance fro[m] our object,” Thompson recounted, “untill the day began to break which advan[ced] so fast as to make it impossible to arrive at the works before broad day light . . . and here the glorious pursuit was gone.”[9] By the time the expedition returned on February 19, the cold and lack of supplies had taken a grizzly toll. “Many men froze to death with only about thirty to forty of the regiment being fit for duty on their return,” recounted one sergeant.[10] Thompson was among those suffering the effects of exposure. “We had one hundred and thirty most bit with the frost. . . . I am myself one of the unfortunate number, but by the frequent applications I have made, my feet are much better, and I flatter myself will soon be well.”[11]

Likely because of his involvement in the ill-fated Willett expedition, when the orders from Washington arrived at Fort Rensselaer on April 17, Thompson was chosen to lead what needed to be an equally hasty expedition to Lake Ontario. Thompson chose to keep his party small. “I then Selected one Bombardier of my own detachment, one Serjeant of Willetts Levies, and One of the Chief Stockbridge Indians,” he recorded, “My Chief Guide and Interpreter I was to take at Fort Herkmer on my way up the River.”[12] He hoped to embark early the next day. As rumors of peace and Thompson’s mission spread, the local people clamored to learn the fates of their loved ones. “The inhabitants about the Country hearing a flagg was going to Oswago,” noted Thompson, “earnestly Solicited that I might be detain’d untill Eleven OClock that they Might have an oppertunity of Writing too and enquiring of Many of their friends whom the Indians had taken from time to time.”[13]

The widespread suffering Thompson described among the local inhabitants is perhaps the most salient aspect of his account of the war’s end in Western New York. The civil war that raged across the Mohawk Valley had been particularly fierce as rebels, Loyalists, British regulars, and diverse Indigenous peoples engaged in violence that left deep scars on both the land and people. Traveling roughly the same route as Thompson would take a year later, Peter Sailly, a recent immigrant, described the devastation. “The inhabitants have suffered more from the late war than in other sections,” an observant Sailly recorded in his diary, “It would seem that Nature itself were in league with the enemy to desolate the country, for the land, naturally fertile, has been unproductive the present year. The most beautiful country in the world now presents only the poor cabins of an impoverished population who are nearly without food and upon the verge of starvation.”[14] Sailly, a visitor, attributed the widespread hunger, in part, to nature. Thompson blamed a more familiar enemy: Natives and the common practice of spiriting away captured locals.[15] As he explained,

These unhappy people, among the whole you will find but three or four men to help them through their difficulties, the savages made it an invariable rule to put every man to death they took which they have exercised to a great amount—The widow and daughter to stop the cries of the Hungry infants have taken up the fatigues of the farm you will se[e] the poor creatures cut[t]ing of wood, threshing of Grain, and performing the other laborious kinds of work.[16]

But if Thompson was quick to blame the wartime “savagery” of Natives, a closer read of his writing reveals a more complex reality. Thompson had explained that Natives had, without exception, killed the men they captured, but in his diary he noted that for a few of the local people who enquired of loves ones spirited away, “On my return . . . I was a Joy full Messenger,” suggesting a propensity to embellish stories of Native violence—a tendency common among Patriots in the region.[17] As historian Jim Piecuch has shown, tales of exegeted violence meant that later historians often “ignored, downplayed, or attempted to justify the brutality with which Americans treated their enemies.”[18]

This habit of overstating Native ferocity does not negate the very real threat of violence Thompson and his men faced, and Thompson’s description of his travels captures the contest that continued to rage for the lands of Western New York in 1783. After his delayed departure from Fort Rensselaer, Thompson and his men made their way along the western banks of the Mohawk River, stopping only for a brief lunch at the home of Peter Davitse Schuyler, before arriving, shortly after sunset, at Fort Herkimer, among the most western American strongholds in the region. Here, it appears Thompson first grappled with the immensity of his charge. In the late eighteenth century, there existed numerous manuals and guidebooks for officers and enlisted men covering all manners of drilling, fortification, warfare, and even retreat.[19] Few discuss the rules governing the cessation of hostilities. Perhaps Thomas Simes, British officer and author of the oft-consulted The Military Guide for Young Officers, came the closest, defining a “Cessation of arms”:

When a Governor of a place besieged, finding himself reduced to such an extremity, that he must either surrender, or sacrifice himself, his garrison, and inhabitants, to the mercy of the enemy, plants a white flag on the breach, or beats the chamade to capitulate; at which both parties cease firing, and all other acts of hostility, till the proposals be either agreed to or rejected.[20]

Thompson’s circumstances were much more challenging than those described by Simes. He was sure the party carried the universal sign of truce: a white flag. He “placed a white flagg on the end of a Spontoon, [which] I gave to the Serjeant to carry.”[21] But unlike the capitulating forces described by Simes, who had the advantage of being in the same place as the party they were negotiating with, Thompson and his men needed to cross a vast, hostile landscape. Given his experience in the Willett expedition, Thompson was also convinced he needed to prepare for challenging circumstances, which he believed necessitated him taking a weapon. As Thompson explained, “Considering the many difficulties we had to encounter before we reachd that distant Garrison, I resolved therefore to take One musket and plenty of powder and Shott. That if we shou’d by any accident loose what provision I had laid up, I might be enabled to hunt.” The other officers attempted to dissuade Thompson from this plan. Any hostile Natives the party encountered, they argued, would see the weapon as an implement of war, and in Thompson’s words, “As they are not very remarkable for their faith, might fall on and Sacrifice each of us.” “Any One who is acquainted with the disposition of these Savages wou’d very Naturaly conceive these Opinions very Plausible,” he despairingly added. Although Thompson believed himself more trustworthy and “civilized” than the Native people, he outlined his own deceit without the least indication of shame. “I resolved that one of the Men shou’d take the Shortest Musket and Roll it up in his blanket, which really could not be discover’d by any one.”[22]

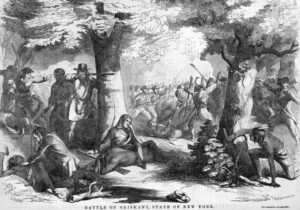

Having employed David Schuyler of Fort Herkimer as guide and interpreter, the five men set out at 8 in the morning on April 19. From the beginning, the fighting that had ravaged the region slowed their progress. The party was forced to traverse two marshes because, as Thompson explained, “The several bridges and passes in this Swamp [had] been broken up and destroy’d . . . by a party of British troops and Indians that retreated [this] way, after, burning and destroying the fine Settlements of New German Town, German flatts, fall Hill, and Canajoharie.” Coming to the location where, on August 6, 1777, Nicholas Herkimer’s American forces had been ambushed by Sir John Johnson’s men in the Battle of Oriskany, the scars of war were more chilling. “I went over the ground where General Herkimer fought Sir John Johnson . . . one of the most desperate engagements that has ever been fought by the Militia,” Thompson reflected, “I saw a vast Number of human Sculls and bones scatterd through the woods.”[23] After crossing Oneida Creek, he and his men “Arrived at Fort Stanwix,” where again, the destruction of the war was apparent, and Thompson paused a moment to appreciate it. “I took a View of the ruins of the Fort as well as the Posts that Lt. Colone[l] St Leger had when he with a party of British Troops and Indians besieged the Garrison.”[24] Although the worst of the fighting had passed, its reverberations remained pronounced.

Amid this tumultuous environment, Thompson’s reliance on friendly Natives, especially the Stockbridge Indian who traveled with him, was evident. Shortly after departing Fort Herkimer, the party encountered a few groups of Oneidas who were friendly but unable to furnish the mission with either supplies nor any valuable information concerning enemy scouts or troop movements in the region. But from the first day of their expedition, the Stockbridge Indian provided invaluable support. Thompson’s men departed amid a “most prodigious Snow Storm” on the 18th, and that evening, the Stockbridge Indian led the party in the assembly of a shelter.[25] They “immediately began to Search for bark, which the[y] soon began to make a make a Wigwam for the night,” he explained.[26] The next night, Thompson was particularly grateful for the Native’s shelter. “The whole of the night we had the most tremendious howlings from Wolfs and other Wild beasts,” he described, “many of which approached us very Near but keeping up large fires, they did not venture to do any mischief.”[27]

As they neared Lake Onieda on April 19, the Stockbridge chief played an even more critical role in the party’s logistics. Thompson planned to cross Fish Creek and then continue along the north shore of the lake. But the Stockbridge Indian approached Thompson with a more expedient option. “The Indian came to me and told me that a few weeks before he had been on a Scout to the Three Rivers,” Thompson explained, “and on his return to The Garrison, as crossing the Oneida Creek he discovered three flatt bottomd boats with Oars” that would make it possible to travel on the lake rather than the difficult march around it. With the memory of Willett’s expedition fresh in his mind, Thompson carefully considered the reliability of this information, but concluded that he “had no room to doubt the truth of what he had said.” “I resolved to make the Serch,” he explained, “which of the attempt if not successfull would retard me but a few hours, and if successfull . . . releave me from the great fatigues which I must have encountered by crossing the long and very tedious swamps, Rivers and Creeks on the North side of the Lake.”[28] The search took them into the next day, but yielded a slightly damaged boat. The party was able to fashion both oars and a sail. As Thompson described, “The Indian bringing in a large piece of board, we soon converted it, to Oars, Puting a hole up in the Middle of the boat, we put up our blankets for sails and the Indian finding some green bark we made halyards to geuen [?] our sail. About three OClock . . . I set sail from the mouth of Wood Creek into the Oneida Lake,” Thompson explained.[29]

Thompson and his men reached the western shore of the lake on the 21st and proceeded quickly down the Onieda River to where it met Three Rivers, where they encountered the enemy for the first time in their expedition. The scouting party was made up of eight Natives led by “two White Men and one Old Indian” all of whom “appeared to be much surprised” at the news Thompson carried as “no such intelligence had been received at the Garrison of Oswago.”[30] Although there was some clamor among the Natives, one of the British officers, Lt. John Hare of Butlers Rangers, assured Thompson that they would escort the party safely to Lake Ontario. When they arrived at the river’s mouth the following day, British regulars blindfolded Thompson and escorted him into the fort to meet with the commanding officer, Maj. John Ross.[31]

While Ross greeted Thompson with “the utmost politeness,” he was concerned about the information being relayed as it was “very different from what he had lately Recd from Genl Haldiman.”[32] According to Ross, far from indicating a coming end to hostilities, Fredrick Haldimand, who served as governor of Quebec, had instructed him to “prepair with every exertion for a defence of his Garrison, That it was expected the American troops woud beseige his Garrison the begining of May.” Ross explained that he would relay “the dispatches to Genl [Allan] McLane at Niagara, and take his opinion, at the same time assuring me upon his honor That every scout of his shou’d be immediately call’d in to communicate the purport of These dispatches as soon as possible.”[33]

Thompson also recorded that while surprised, Ross seemed to experience a measure of relief. “Major Ross took the Opportunity to Observe in the most polite manner, That as I had given The first intelligence of War subsiding,” Thompson explained, and “took occasion to Observe that he was very happy a period was put to such an unnatur[al] War.”[34] Most of Ross’ distress seemed to arise from his complicated relationship with his Native allies. According to Thompson, when he provided Ross the letters he carried from families enquiring about captured loved ones, the commander promised him the issue would be “duly attended to.” But he also claimed that he had taken every measure to “prevent the Murdering of any prisoners”; nonetheless, “It was impossible for any Officer to controul the savages in attendants on any detachment and farther really believed That many cruel depredations had been committed by them, That was not made known to any but Themselves.”[35]

But if Ross was happy to see an end to the fighting, neither he nor the fort’s other officers were pleased about the reported terms of peace. “Nothing seemed to affect him More then coming to the bounderies of the United States,” Thompson recorded. “He ran, got out his maps and began to traverse the boundary line to find that the strong and important Post of Oswago, Niagara, & Detroit had been ceded by the British Court to the United States, and what was still more so, to leave in such ampble Order, Those works That had cost so many days hard fatigue.”[36] Thompson noted that he recognized one of the officers most affected by the news, was Capt. William Crawford of the 2nd Battalion, King’s Royal Regiment of New York, “a person That had Joined the British Standard when they took Possession of the City of New York.” While Thompson was nothing but complimentary of Ross’ behavior, his description of the Loyalist officers was less flattering, revealing the enduring hostility Patriots had for their former friends and neighbors who chose allegiance to the crown. Thompson claimed that upon learning of capitulation, an arrogant Crawford haughtily boasted that the terms of peace made little difference to him as “he had made more money on the side of the Question he had taken, Than if he Shou’d remain in an American Army one hundred Years.” “This man appear’d to be really ignorent of the cause he was fighting for,” an indignant Thompson retorted in his journal.[37]

The British and Loyalist officers were disappointed, but Thompson worried more about the outrage that spread among their Native allies. Shortly before Thompson’s departure a few days later, Ross informed him that news of the war’s end reached the Natives, who worried about what peace would mean for them. Haldimand’s secretary had previously written to Ross, instructing him to assure the Natives, “They will never be forgotten. The King will always regard them as his faithful children.”[38] The news Thompson carried seemed to contradict that promise. “The savages had become clamorous,” Thompson recorded, “for some person had told them all their canos was to be taken from Them, and that they was to be drove away as far as where the sun went down.” He also noted that they had made threats against the party on their return journey. Thompson was sure he knew who leaked the news—likely one of the “many disappointed Tory Wretches Loyal Subjects [who] had been base enough to propagate among the savages . . . that I ought to be an Object for their Resentments.” He was happy to allow Ross to send a detachment of soldiers with the party as far as they deemed necessary for their protection.[39]

Thompson had successfully delivered news to the British garrison on Lake Ontario of an end to the fighting, but, his journey yielded few immediate results. The British would not evacuate their stronghold for more than a decade, when in July 1796, the last troops departed across the lake.[40] He would die at West Point in 1806, long before the fort’s value became evident during the War of 1812. But the Thompson’s report provides a rare glimpse into both the contested borderland of Western New York at the war’s end and one American’s perspective of relations across the region. The negotiators at Paris had theoretically wrestled the territory from Great Britain; Thompson’s account reveals that the new American government had little ability to assert control over it. Moreover, the fighting left the region in ruin and created deep divides among diverse peoples, further hampering any entity’s ability to secure its influence in the area. As a variety of people in both the United States and Canada mark the Semiquincenntial, Thompson’s diary serves as an important reminder of both the toll of war and the numerous challenges that remained long after the Revolution ended.

[Research funding for this piece was provided by a Keith Armistead Carr Fellowship from The Society of the Cincinnati and a University of Tampa Research Innovation and Scholarly Excellence Award/David Delo Research Grant. Many thanks to Fort Plank Historian, Ken D. Johnson, for his invaluable insights on the location of Fort Rensselaer, the clarifying notes he made on an earlier draft of this article, and for the work he has done to preserve the history of the Mohawk Valley. See his website, Fort Plank: Bastion of My Freedom, Colonial Canajoharie, New York, www.fort-plank.com/. My thanks also to Herkimer County Historical Society Volunteer Researcher, Kathy Huxtable for digging up information that allowed me to more easily understand the many locations Thompson referenced.]

[1] Capt. Alexander Thompson, “Journal of a Tour from the American Garrison of Fort Rensselear in Canajoharie on the Mohawk River to the British Garrison of Oswago as Flagg to announce a Cessation of Hostilities on the frontiers of New York, Commenced Friday, April 18th 1783,” Library of the Society of Cincinnati, Washington, DC [SOTC], final report, 1-2. Thoughout this piece, I have aimed to keep Thompson’s spelling original, editing only for punctuation where needed. The “Fort Oswago” that Thompson refers to is the modern Fort Ontario. In the mid eighteenth century, there were two functioning forts on either side of the Oswego River along Lake Ontario. On the western banks of the river lay Fort Oswego, and a small, largely unfinished redoubt, while on the river’s eastern shores was a newly constructed blockhouse called Fort Ontario. French forces under the command of Montcalm burned each to the ground in August 1756; British troops built a new pentagon-shaped fort on the site of Fort Ontario, which they occupied until 1777 and then secretly repaired and occupied again in 1782. On the history of Forts Oswego and Ontario, see Bud Hannings, Forts of the United States: An Historical Dictionary, 16th through 19th Centuries (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2006), 318 and Charles Prestwood Lucas, Historical Geography of the British Colonies, Vol. 5: History of Canada, Part I (New France) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1901), 256.

[2] On the celebrations, see “Schedule of Events, Patriots’ Day Weekend,” Lexington250, lex250.org/event/patriots-day-weekend/.

[3] Despite the excitement that surrounded the Bicentennial in 1976, there was little, other than a proclamation by President Reagan, to mark the anniversary of the war’s end in 1983. See “Proclamation 5082—200th Anniversary of the Signing of the Treaty of Paris,” Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, National Archives, accessed May 30, 2025, www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/proclamation-5082-200th-anniversary-signing-treaty-paris. Given that most exiled Loyalists settled in what are now the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Ontario, there was more notice of the war’s conclusion in Canada. For a good review of the role the Loyalists played in Canadian memory around the Bicentennial, see Elwood Jones, “The Loyalists in Canadian History,” Journal of Canadian Studies 20, no. 3 (Fall 1985): 149-156.

[4] See Nellis M. Grouse, Forts and Block Houses in the Mohawk Valley, Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association 14 (1915): 75-90, especially 87-89.

[5] Alexander Thompson to his brother, February 24, 1783, The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History and Biography of America, Ser. 1, v. 3, no. 6 (June 1859): 186-187. Many thanks to Fort Plank Historian, Ken D. Johnson, for alerting me to this letter.

[6] On some of these raids, see William Martin Beauchamp, “Indian Raids in the Mohawk Valley,” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association 14 (1915): 195-206, especially 201-206. See also, Richard J. Werther, “Marinus Willett: The Exploits of an Unheralded War Hero,” Journal of the American Revolution, September 20, 2022, allthingsliberty.com/2022/09/marinus-willett-the-exploits-of-an-unheralded-war-hero/.

[7] From Newburgh, Washington wrote that although Willett requested an additional detachment to prevent enemy raids, Washington found the request unreasonable. “I dare say you must be sensible this is not the case,” Washington responded to Clinton of Willett’s request, “How far it may therefore be expedient to call forth an additional aid of Militia, I shall submit to your Excellencys judgment, as you are better acquainted with the circumstances of the frontier, the strength of Willets command, and probably the state of the Enemy at Oswego, than I am. In the mean time, I wish to be informed as far as may be in your power, of the force of Willet’s Corps now assembled on the Mohawk, also of the strength of the Enemy at Oswego, of which I have as yet had only vague and unsatisfactory accounts.” George Washington to George Clinton, July 30, 1782, George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries 3C, Varick Transcripts, Letterbook 4, Library of Congress, tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/mss/mgw/mgw3c/004/004.pdf. For Willett’s son’s account, see William M. Willett, А Narrative of the Military Actions of Colonel Marinus Willett, Taken Chiefly from His Own Manuscript (New York: G. & C. & H. Carvill, 1831), 91-92. See also, George Washington to Marinus Willett, December 18, 1783, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10242. Many thanks to Fort Plank Historian, Ken D. Johnson, for pointing me to this historical debate.

[8] Alexander Thompson to his brother, February 24, 1783, The Historical Magazine, 186-187. See also, “African Descended Soldiers at Fort Schuyler & in the Mohawk Valley,” National Parks Service, accessed June 4, 2025, www.nps.gov/articles/000/patriots-of-color-at-fort-schuyler-in-the-mohawk-valley.htm.

[9] Alexander Thompson to his brother, February 24, 1783, The Historical Magazine, 186-187.

[10] Quoted in “‘…Many Men Froze to Death…,’” “The American Revolutionary Episodic; Or, The Fort Stanwix Blog,” National Park Service, February 05, 2022, www.nps.gov/fost/blogs/many-men-froze-to-death.htm. See also, Willett, А Narrative of the Military Actions, 92-93.

[11] Alexander Thompson to his brother, February 24, 1783, The Historical Magazine,186-187 and Willett, А Narrative of the Military Actions, 92.

[12] Thompson, “Journal of a Tour,” 2.

[13] Ibid., 3.

[14] Peter Sailly, diary, May 29, 1784, in Peter Bixby, “Peter Sailly (1754-1826): A Pioneer of the Champlain Valley with Extracts from His Diary and Letters,” New York State Library History Bulletin, 12, February 1, 1919 (Albany: The University of the State of New York, 1919), 60.

[15] On the spiriting away of captured prisoners during “mourning wars,” Daniel Richter notes, “In many Indian cultures a pattern known as the ‘mourning-war’ was one means of restoring lost population, ensuring social continuity, and dealing with death.” “War and Culture: The Iroquois Experience,” The William and Mary Quarterly 40, no. 4 (October 1983): 529.

[16] Alexander Thompson to his brother, February 24, 1783, The Historical Magazine, 186-187.

[17] Thompson, “Journal of a Tour,” 4. Furthermore, contrary to Thompson’s claim, a list of the fifty-two people taken prisoner by Natives during an August 2, 1780 raid around Fort Plank lists only women and children. See Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York (Albany: J.B. Lyon Company, 1902), 6: 77.

[18] Jim Piecuch, Three Peoples, One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South, 1775–1782 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2008), 5.

[19] For example, see Humphrey Bland, A Treatise of Military Discipline… (London: Sam Buckley, 1727) and Richard Kane, Campaigns of King William and Queen Anne… (London: J. Millian, 1745).

[20] Thomas Simes, The Military Guide for Young Officers… (Philadelphia: Humphreys, Bell and Aitken, 1776).

[21] Thompson, “Journal of a Tour,” 4.

[22] Ibid., 6-8.

[23] Ibid., 11, 14-15, emphasis original. On the Battle of Oriskany, see Paul A. Boehlert, The Battle of Oriskany and General Nicholas Herkimer: Revolution in the Mohawk Valley (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013).

[24] Thompson, “Journal of a Tour,” 11, 14-15, emphasis original.

[25] Ibid., 8.

[26] Ibid., 12.

[27] Ibid., 17.

[28] Ibid., 19.

[29] Ibid., 25, emphasis original.

[30] Ibid., 31.

[31] Ibid., 29-37, quote p. 30.

[32] Ibid., 34.

[33] Ibid., 35-36. On McLane, see G. F. G. Stanley, “Maclean, Allan,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maclean_allan_4E.html.

[34] Thompson, “Journal of a Tour,” 40, 42.

[35] Ibid., 42, 41.

[36] Ibid., 43.

[37] Ibid., 44.

[38] Fredrick Haldimand to Sir John Johnson, September 9, 1782 as quoted in Alan Taylor, The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 106.

[39] Thompson, “Journal of a Tour,” 46, emphasis original.

[40] On the contests that continued long after the Revolution across the region, see Alan Taylor, “The Divided Ground: Upper Canada, New York, and the Iroquois Six Nations, 1783-1815,” Journal of the Early Republic 22, no. 1(Spring 2022): 55-75.

Recent Articles

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...