The engagement between Abraham Buford and Banastre Tarleton at the Waxhaws has attracted controversy since it occurred. Buford has had supporters and detractors, just as students of the battle have exonerated or excoriated Tarleton. The problem has been that this kind of black-or-white determination suggests one side was entirely at fault, the other entirely blameless. Most things in life present in shades of gray, and the Waxhaws battle is also nuanced in this way. There is the possibility of reconciliation of opposing viewpoints, a common ground where neither Tarleton’s aggression nor Buford’s incompetence provided the sole impetus for the result.

Every aspect of the battle and its outcome has been the subject of debate. There are several questions about the Waxhaws, and the answer to one does not preclude an opposing answer to the next. For example, the first question of tremendous importance was whether a slaughter of Americans occurred. The next logical question is whether the massacre, if one occurred, amounts to an atrocity rather than an overwhelming, asymmetrical victory. This question warrants examination.

In order to grasp the events at the Waxhaws, the separate questions need to be broken out and studied separately. The key issues for analysis are, in order: one, was there a massacre, two, if so, was it an atrocity that today would be characterized as a war crime, and three, if it was an atrocity, who was responsible for it? With any luck, if we answer these questions correctly, a compromise will appear between the two sides in the ongoing debate.

The Facts

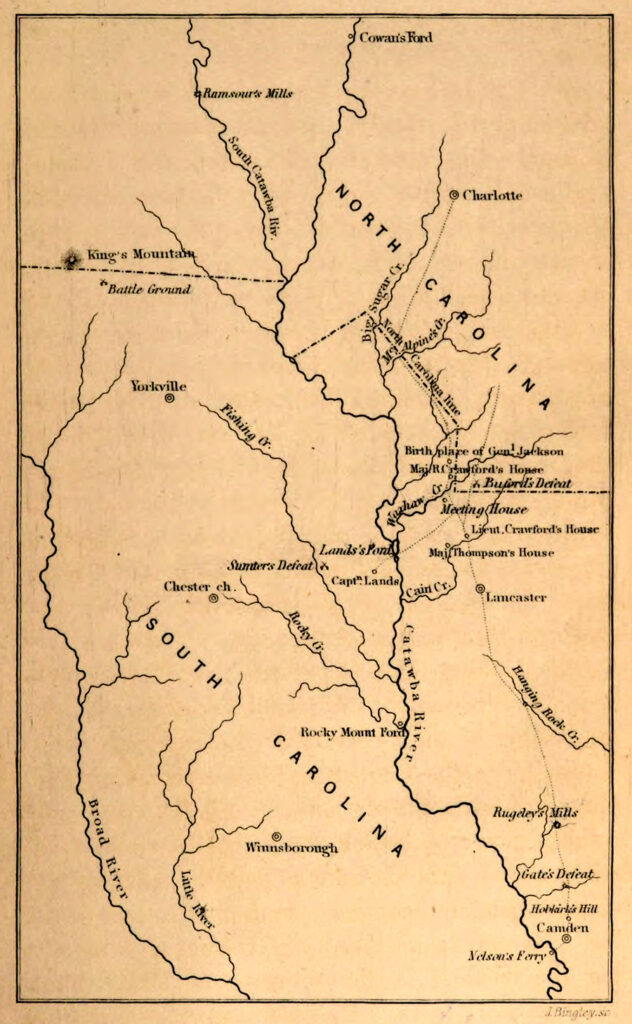

Col. Abraham Buford was the commander of a unit of Virginia Continental infantry sent to Charlestown in the spring of 1780 to bolster the defenses of the beleaguered southern metropolis. Buford never entered they city, and when it surrendered on May 12, 1780, he found himself leading the last intact Continental formation in the deep south. With Charlestown in British hands, the rebellion in South Carolina was crumbling around him. He moved northward. His goal was North Carolina, safely out of British reach and offering the possibility of uniting with other forces to create a formidable block to British efforts north of South Carolina. Other survivors gravitated to him, and his force moved north with infantry, some cavalry, and two field pieces with their crews, a total of 400 men.[1] Brig. Gen. William Caswell, commanding a force of North Carolina militia, also found himself outside the gates of Charlestown when its defenders capitulated. He joined Buford on the march north as far as Camden. On May 25, Caswell took his 700 men northward. Buford departed Camden the next day.[2]

Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis, at the time deputy to Gen. Henry Clinton in the British command in the southern theater, started on a chase of Buford. Hamstrung by the difficulties of moving a large army, Cornwallis detached Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton with 270 men, dragoons, mounted infantry, and a single field piece, to pursue Buford with vigor.[3] After a forced march of fifty-four hours, in which he exhausted men and horses, Tarleton caught Buford at the Waxhaws, a border region joining North and South Carolina. Tarleton demanded Buford’s surrender; Buford refused. Tarleton formed his men for battle and attacked. The Americans fought back, but unsuccessfully. The American line broke.

At this point, the narratives diverge.[4] Buford asserted that he saw further resistance futile, and sent a flag of truce to Tarleton, which the latter refused. Tarleton mentioned nothing about a flag from the Americans. Both commanders recalled Tarleton’s horse was shot and he was pinned beneath it. To Tarleton this was the key moment because, as he was out of the battle trying to extricate himself, his soldiers, driven to outrage by the apparent loss of their commander, commenced, as Tarleton acknowledged, the “slaughter” of the Americans. Buford did not see Tarleton’s unhorsing as important. To him, the action pivoted when his men grounded their weapons and asked for “quarter,” and in this position of surrender, were cut down by the British. Tarleton insisted he stopped the slaughter as soon as he was remounted.

The casualty figures were evocative. Tarleton reported 113 Americans killed in action, 53 unwounded prisoners of war, and an unprecedented 150 wounded too severely to move off the field. The British lost 5 killed and 12 wounded.

Was There a Massacre?

The concept of a massacre eludes a precise definition. The idea elicits strong, visceral emotions but has few concrete attributes. Webster’s dictionary defines it as “the indiscriminate, merciless killing of number of human beings,” and this definition serves as well as any.

This phase of the battle requires little discussion. Here, we take Tarleton at his word. The word slaughter resonated in the eighteenth century much as it does today. Tarleton’s recognition of the slaughter of Americans was a complete admission of the enormity of the actions of his men. Buford decried the result, reporting the loss of two-thirds of his officers and men under deplorable conditions.

There were other reports, uniformly describing a massacre. The most poignant evidence is derived from the wounds suffered by the survivors. As one among many, Alexander Garden recalled an account from “an officer of our army, whose accuracy it is impossible for me to doubt,” who visited the wounded after the battle, and recorded an average of sixteen wounds per man.[5] The most accessible recounting of the mass tragedy of the wounded Americans is in Leon Harris’s summary paper, “American Soldiers at the Battle of Waxhaws SC, 29 May 1780,” dealing with the pension applications of survivors.[6] Harris extracted the reports of the wounds suffered by the American soldiers, a wrenching account of men slashed and hacked to pieces.

The Americans were not alone in believing a massacre had happened. An officer of the British Legion crowed that “in three minutes after the attack was begun, there was not a rebel on the field that was not levelled with the ground.”[7] Charles Stedman, a Loyalist officer in the British service, lauded the British victory but screamed outrage that “the virtue of humanity was totally forgot.”[8] While Stedman accused no one of impropriety, he was certain that a massacre had occurred. There seems no reason to dispute these reports, admitted by the British, that Buford’s men were massacred at the Waxhaws.

Was It an Atrocity?

Tarleton’s point, distilled to its essence, was that it was possible to have a massacre without an atrocity, what today would be war crime. He argued that his men were simply too vigorous in pursuing a legitimate goal. Overeager, to be sure, but not blameworthy. In a hypothetical world, one can construct a picture of a massacre without an accompanying atrocity. A single swipe of cavalry against unprotected infantry, vision obscured by smoke and the fog of war, might make such a thing possible. Assuming this to be the case, the facts of the Waxhaws become essential. Buford was emphatic that his men were cut down where they stood, after seeking quarter. If true, a classic war crime.

There is little to be gained from comparing Buford against Tarleton on this point. They disagreed; not much more may be said. The most useful evidence has arisen from analyses of the pension applications and bounty land warrants of survivors.

Leon Harris conducted a statistical analysis of the pension applications of Waxhaws veterans, and compared them to the applications of veterans of Camden, Cowpens, Guilford Courthouse, and Eutaw Springs, chosen for their references to sword wounds, the great commonality with Waxhaws.[9] Harris determined that Waxhaws was the only battle where soldiers received sword wounds to arms or hands in numbers exceeding the norm by a statistically significant margin. He concluded that Tarleton’s dragoons had attacked Buford’s men after they grounded their weapons.

Similarly, Waxhaws was the only battle where the men were wounded by both swords and bayonets in greater numbers than those wounded by swords alone. At Waxhaws, of thirty-two applicants with sword wounds, seventeen also received bayonet wounds. A more typical example was Cowpens, where eighteen applicants bore sword wounds, but only one man also received a bayonet thrust. The data compelled a single conclusion: Tarleton’s infantry attacked Buford’s men after they had been wounded by the cavalry.

The data analyses confirmed the narrative accounts of the wounded veterans. The scale of the wounding was unprecedented, far out of any expectations. A fulcrum in reconciling the Tarleton and Buford narratives was the fact that the idea of an atrocity was not a late gloss added for its impact as propaganda. The Waxhaws was not a case in which later generations created the myth of a massacre for their own agendas. Actually, the sequence was reversed: the first account of the battle, Buford’s report of June 2, 1780, asserted that an atrocity had taken place.[10] The revisionism arose on the British side, with Tarleton acknowledging a massacre of the Americans, but insisting it fell short of an atrocity.

Tarleton’s plea of justification for the actions of his men draws us to the question of blame. The data overwhelm debate on the first two questions: there was a massacre, and it occurred in circumstances amounting to an atrocity, a war crime. The resolution of the final question, who was to blame, is much less apparent.

Who Was to Blame?

Tarleton’s efforts to excuse the conduct of his men, that they were enraged at what looked like his fall in battle, and that they ran out of control while he was struggling with his fallen horse, has always been unpersuasive. At best, it fell into the “lame pretext” school of thought. He gained more traction blaming Buford. The American, as Tarleton told the story, ordered his infantry to hold fire until the charging British cavalry was ten yards distant. Buford’s order was inexplicable, one of a series of orders that defied common sense. As another example, Buford had two artillery pieces in his army. Nevertheless, when confronted with the reality of Tarleton’s pursuit, he sent the artillery with his baggage northward.[11] Ultimately, the British formed for battle, within artillery range, yet unmolested by American guns. Even with this in mind, while Buford’s incompetence might explain the force of the British victory, it could neither explain nor justify an atrocity.

There were other narratives beyond those of the commanders and the pension applicants. Dr. Robert Brownfield wrote a passionate tirade against Tarleton.[12] He bemoaned the fact that “the demand for quarters, seldom refused to a vanquished foe, was at once found to be in vain;─not a man was spared.” He went much further. He insisted that the picture of Americans begging for quarter only presented an opportunity “to gratify that thirst for blood” that marked Tarleton’s character. While one may accept or reject Brownfield, we will search his writings in vain for common ground with the opposition.

Another American eyewitness was Henry Bowyer. Bowyer served as Buford’s adjutant in the battle. He left a narrative at odds with much of what the other Americans had to say.[13] The story was committed to writing by someone other than Bowyer, and it bore unusual marks. For example, the scribe rendered the American commander as “Beaufort,” and Bowyer appeared as “Boyer” as often as it appeared correctly. Overlooking these scrivener’s errors, Bowyer delivered a body blow to the American narrative. It was the first, visible crack in the all-or-nothing view of the engagement.

Bowyer described a give-and-take not present in any of the other narratives. He wrote that Buford sent him forward with the flag to Tarleton to negotiate surrender terms. As he arrived, Tarleton’s horse was shot from under him. Tarleton, enraged and frustrated, ordered his men to cut Bowyer down. Bowyer parried the sword thrusts. Two American officers posted nearby had followed Bowyer’s movements carefully, and seeing he was desperate straits, ordered their men to fire on the dragoons menacing Bowyer. Their fire allowed Bowyer to escape. As Bowyer told the story, at this point, “the overwhelming force of the British then prevailed, and a dreadful massacre of the detachment followed.” By this account, the British were enraged over the Americans’ firing after they had offered a flag of truce. Their anger “impelled them to acts of vengeance that knew no limits.”

Bowyer’s story has received a mixed reception. His version suited neither side in the debate. The British were unwilling to acknowledge they killed any Americans after a flag of truce. Tarleton, as one obvious example, omitted any mention of a flag from his memoir. He left no opening for a suggestion the British caused casualties in an unlawful way. At the same time, the Americans were no more pleased to read what Bowyer said. Although trying to save a comrade, two platoons of infantry fired on British soldiers, literally in the shadow of the flag of truce. Their firing provided the immediate trigger for the massacre. Bowyer’s statement appeared in redacted form in a later treatise published in the United States.[14] The later version discussed his heroism in taking the flag forward in the midst of the fighting, but excised any idea that Americans fired on the British after the flag went forward.

One might readily disregard Bowyer’s statement. Put in writing by someone else, it bore obvious errors on which one may choose to focus. More to the point, however, was its inconsistency with the other witnesses. The pension applicants did not speak to the idea of an atrocity, which made sense. The purpose of their applications was to obtain compensation, not memorialize a historical event for the ages. The few witnesses who addressed the issue of American casualties after surrender─Tarleton, Buford, and Brownfield─told stories vastly different from the one related by Bowyer.

Ultimately, it is the story’s inconsistency that proves its worth, because there is a body of information from other eyewitnesses that energized the version asserted by Bowyer. The Moravian Church kept detailed records of life in the communities around Salem, North Carolina. Bishop Johann Michael Graff recorded that on June 5, 1780, an officer and twelve men entered Salem, relating a story of an American defeat below Charlotte.[15] These men left in a few days, but more trickled in, all moving north, telling stories of the defeat and of a large number of wounded soldiers in nearly Abbott’s Creek, North Carolina. On June 8, three men arrived without food or the means to obtain it. A kind Moravian gave them bread, and they told the story of their misfortune. They were at a “bloody action” in South Carolina.[16] The matter progressed quickly, and “before they were aware of it,” the British surrounded them. Realizing they were beaten, they laid down their arms. They then reached the heart of the matter: “as the English commander rode up one man seized a gun and shot at him, and then the massacre began.”

The Moravian narrative suffers from having passed through too many hands. The soldiers related the story to the man who gave them bread, who told the bishop, who wrote it down. The Moravians spoke German, which was the original language of the bishop’s journal, and we have no idea how well the interlocutors communicated in the two languages. The Bowyer narrative, as well, had too many opportunities for misconstruction. The old party game “telephone” comes to mind in discussing the two stories. To these obvious problems we add the less apparent problems of the fog of war; one has no idea what piece of the big picture was shared by these three soldiers.

Nevertheless, even with these deficiencies in mind, the Moravian and Bowyer narratives leaned on a strong, essential commonality. The Americans violated the flag of truce, and the British, enraged, responded with an atrocity. This version explains Buford’s adamant position as well as Tarleton’s tepid defense. Buford, facing condemnation for a disaster of epic proportions, needed to blame the entire result on an unscrupulous enemy. Partial blame was not enough; he needed Tarleton to be evil to explain the entire matter. Tarleton, facing scorn from both sides of the Atlantic, could not afford a whiff of criminality. He needed Buford to appear the raging incompetent, his men well-intentioned but overenthused.

Reality rarely arrives so neatly packaged. Military history, as any endeavor, is imbued with nuance. While we may prefer an orderly arrangement of winners and losers, the facts remain that most battles turn on large numbers of factors and a wealth of decisions that resist easy categorization. The Waxhaws is best explained outside the facile framework of a demonic Tarleton or an incompetent Buford.

The story told by Bowyer and the Moravians represents, at last, a way to reconcile everything related by the eyewitnesses to the battle. The pension applicants, in their narratives or through their wounds, all spoke to the extent of the massacre. Buford and Brownfield were truthful in asserting the British killed Americans after they surrendered. Tarleton, correct in asserting Buford made terrible tactical decisions, did not lie when he wrote that his men became enraged just as his horse was shot from under him.

In navigating a series of conflicting accounts, consistency is a polestar. If there is a way to unite all the accounts into a single narrative, the result manifests the power of all the eyewitnesses. In the debate over the Waxhaws, accepting one point of view has required disposing of the other. Those historians denying an atrocity took place have thrown Buford into a metaphorical dustbin. One may discuss the choice in polite terms of credibility or truthfulness, but at bottom, if there was no atrocity, Buford lied.

While outright lies occur, they are much less common than shading or emphasis. It was more likely that Buford and Tarleton chose to emphasize favorable aspects of the story than that one or the other committed a series of bold-faced lies to paper. By accepting the Bowyer-Moravian narrative of the Waxhaws, we can abandon the painful question of which witness lied. No one lied. Both sides, however, shaded their reporting. This fact, of course, comports with human nature. In a disaster the scale of the Waxhaws, there was plenty of blame to go around. Each commander, under pressure after the fact, chose to prepare a report, essentially truthful, but emphasizing certain aspects of the story and obscuring his side’s culpability. Viewed this way, each commander emerges in human dimensions, neither demonic nor robotically incompetent, but subject to the same foibles and temptations as the rest of us.

[1] Banastre Tarleton, History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America (Dublin, 1787), 30. There was no accounting of Buford’s force from the American side, and Tarleton’s numbers have stood by themselves. After the battle, the British counted 316 Americans killed, wounded, and captured, and with survivors, Tarleton’s numbers have confirmation.

[2] William Caswell to Abner Nash, June 3, 1780, in Walter Clark, ed., State Records of North Carolina, vol. 14: 1779 to 1780 (Winston, NC, 1896), 14:833, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0791; William Dobein James, A Sketch of the Life of Brig. Gen. Francis Marion, and a History of His Brigade, From Its Rise in June, 1780, Until Disbanded in December, 1782; Containing Also, an Appendix; With Copies of Letters Which Passed Between Several of the Leading Characters of That Day; Principally From Gen. Greene to Gen. Marion (Charleston, 1821), appendix.

[3] Tarleton, Campaigns, 28. Americans vastly exaggerated Tarleton’s numbers, e.g., Dr. Robert Brownfield in James, Life of Marion, appendix (600 men); Caswell to Nash, June 3, 1780, in Clark, State Records of North Carolina, 14:833 (700 men).

[4] Abraham Buford to Virginia Assembly, June 2, 1780, original in the Thomas Addis Emmet Collection of the New York Public Library, transcription in Jim Piecuch, The Blood Be Upon Your Head: Tarleton and the Myth of Buford’s Massacre (Lugoff, SC: Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution Press, 2010), 61−63; Tarleton, Campaigns, 29−33.

[5] Alexander Garden, Anecdotes of the Revolutionary War in America, with Sketches of Character of Persons the Most Distinguished, in the Southern States, for Civil and Military Services (Charleston, 1822), 285n.

[6] C. Leon Harris, “American Soldiers at the Battle of Waxhaws, SC, 29 May 1780,” August 11, 2021, Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, revwarapps.org/b221.pdf, 6−14.

[7] J. Tracy Power, “The Virtue of Humanity Was Totally Forgot: Buford’s Massacre, May 29, 1780,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 93, no. 1 (Jan 1992), 9.

[8] Charles Stedman, History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War, 2 vols. (London, 1794), 2:193.

[9] C. Leon Harris, “Massacre at Waxhaws: The Evidence From Wounds,” Journal of the Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution 11, no. 2.1 (June 2016), southern-campaigns.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Harris-Massacre-at-Waxhaws.pdf, 2−3.

[10] The idea of an atrocity spread quickly. As early as June 21, an official report to the governor of North Carolina stated the British had killed surrendering Americans, Thomas Person to Thomas Burke, June 21, 1780, in Walter Clark, ed., State Records of North Carolina, vol. 14: 1779 to 1780 (Winston, NC, 1896), 14:833, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0819.

[11] Tarleton, Campaigns, 30. Buford tacitly agreed, reporting only the loss of his cannons, not any use of them. Brownfield agreed only in principle, acknowledging the American artillery remained silent, but blamed the American artillery commander, implying he was a Loyalist interloper. James, Life of Marion, appendix.

[12] James, Life of Marion, appendix.

[13] Alexander Garden, Anecdotes of the American Revolution, Illustrative of the Talents and Virtues of the Heroes and Patriots Who Acted the Most Conspicuous Parts Therein, Second Series (Charleston, 1828), 135−138.

[14] F. Johnston, Memorials of Old Virginia Clerks, Arranged Alphabetically by Counties, With Complete Index of Names, and Dates of Service from 1634 to the Present Time (Lynchburg, VA, 1888), 92−93.

[15] Adelaide L. Fries, ed., Records of the Moravian Church in North Carolina, vol. 4: 1780–1783 (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton Company, 1930), 4:1522−1544.

[16] Bishop Graff referred to the place as Hanging Rock. By convention today, the location is given as the Waxhaws. The veterans and residents of the area may have used any number of designations for the site. The Waxhaws battlefield lies thirteen miles from Sumter’s battlefield at Hanging Rock.

5 Comments

This is excellent analysis working through a difficult set of questions. Much like the work I do with the some of the engagements after Yorktown there are a number of sources that are suspect, terribly confusing, one-sided, and so on. It takes a great deal of work (and headache) to patiently sort through all the historiography and arrive at the best analysis we can today working with what we have, well done, and thank you for this work.

Good article logically presented.

One minor point: Gen. Henry Clinton was actually a Lt. Gen. at this time.

As commander in chief of the army in North America, Henry Clinton held a brevet rank of general, in addition to his army rank of lieutenant general.

Very Good article. I appreciate the research and thought that went into the analysis. My only thought is that another consideration could be the short amount of time between when the first shots were fired and the termination of the battle. It appears from the narrative that the elapsed time was only minutes, not enough time for tired/angry/scared soldiers to make thoughtful decisions. Rather, they were likely reacting rather than reasoning.

My DAR Patriot is William R. Pentecost, who lost an arm at the Waxhaws, so this article is greatly appreciated.

For a long time I have been trying to find out where Abraham Buford served before he was given command of the 4th Virginia Regiment (Buford’s Detachment). If anyone knows, could you please respond here.

Thank you, Deborah Hendrick