“They are by no means such Troops, in any respect, as you are led to believe of them from the [Accounts] which are published.”[1]

So declared General George Washington to his cousin, Lund Washington, nearly two months into his command of the newly formed Continental Army outside Boston. Appointed by the Continental Congress on June 15, 1775 to command this army of New England troops, Washington arrived in Cambridge on July 2. It was an appointment he neither sought nor desired, and he shared his unease at the appointment with his wife:

I have used every endeavour in my power to avoid it . . . But, as it has been a kind of destiny that has thrown me upon this Service . . . it was utterly out of my power to refuse this appointment without exposing my Character to such censures as would have reflected dishonour upon myself, and given pain to my friends.[2]

He repeated his concerns to Burwell Bassett, a relative through his marriage to Martha Dandridge Custis.

It is an honour I wished to avoid, as well from an unwillingness to quit the peaceful enjoyment of my Family as from a thorough conviction of my own Incapacity & want of experience in the conduct of so momentous a concern. But the partiality of the Congress added to some political motives, left me without a choice.[3]

To his brother John Augustine, Washington wrote dramatically that,

I am to bid adieu to you, & to every kind of domestick ease, for a while. I am imbarked on a wide Ocean, boundless in its prospect & from whence, perhaps, no safe harbour is to be found.[4]

He repeated his claim that he did not seek the appointment and added,

I am thoroughly convinced; that it requires greater Abilities, and much more experience than I am Master of . . . but the partiality of Congress, joined to a political motive, really left me without a choice[5]

The political motive behind his appointment was the desire of Congress to select a Virginian to command the army. It was done in hopes of generating greater southern support, particularly Virginian support, for the conflict in Massachusetts. The delegates in Philadelphia recognized the stature Washington held among his fellow Virginians and, given his military experience in the previous war, they viewed him as a shrewd choice to lead the new continental army posted outside Boston.

Washington headed north from Philadelphia on June 23 and was enthusiastically greeted along the way to Cambridge. Worried that he would be disappointed with the condition of the army, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress wrote to him the day after his arrival:

We wish you may have found such Regularity, and Discipline already establish’d in the Army, as may be agreeable to your Expectation. The Hurry with which it was necessarily collected, and the many disadvantages, arising from a suspension of Government, under which we have raised, and endeavour’d to regulate the Forces of this Colony have render’d it a work of Time. And tho’ in a great measure effected, the completion of so difficult, and at the same time so necessary a Task, is reserved to your Excellency[6]

The Congress added that the bulk of the troops were inexperienced in military life and therefore, unprepared for the rigors of camp life.

We would not presume to prescribe to your Excellency, but supposing you would choose to be informed of the general Character of the Soldiers, who compose this Army beg leave represent, that the greatest part of them have not before seen Service. And altho’ naturally brave and of good understanding, yet for want of Experience in military Life, have but little knowledge of [many] things most essential to the preservation of Health and even of Life. The Youth in the Army are not possess’d of the absolute Necessity of Cleanliness in their Dress, and Lodging, continual Exercise, and strict Temperance to preserve them from Diseases frequently prevailing in Camps; especially among those who from their Childhood, have been used to a laborious Life.[7]

Washington’s first orders to the army called for exact returns of all camp supplies and provisions. He announced the names of four new major generals appointed by the Continental Congress, as well as several of his aides. He also announced that all of the provincial troops of the Army of Observation had been placed under the authority of the Continental Congress, “for the support and defence of the Liberties of America. They are now the Troops of the United Provinces of North America,” declared Washington, and he expected the officers to, “pay diligent Attention to keep their Men neat and clean.”[8]

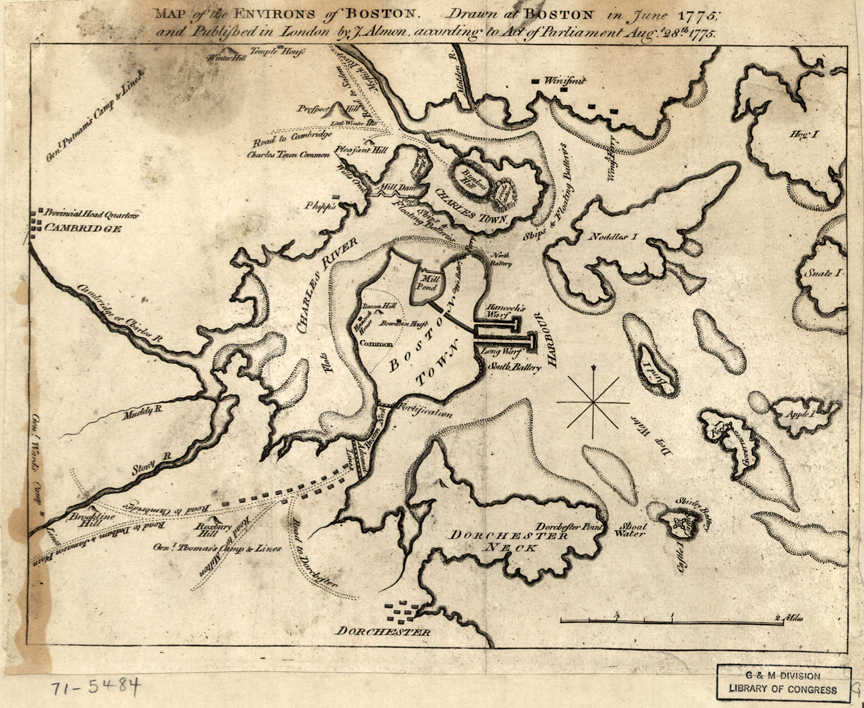

It was a week before Washington wrote to the Continental Congress with his first report from camp. He described the British disposition of troops and then his own:

On our side we have thrown up Intrenchments on Winter & Prospect Hills, the Enemies Camp in full View at the Distance of little more than a Mile. Such intermediate Points as would admit a Landing, I have since my Arrival taken Care to strengthen down to Sewal’s Farm, where a strong Entrenchment has been thrown up. At Roxbury General Thomas has thrown up a strong Work on the Hill, about 200 Yards above the Meeting House, which with the Brokenness of the Ground & Great Numbers of Rocks has made that Pass very secure—The Troops raised in New Hampshire, with a Regiment from Rhode Island occupy Winter Hill: A Part of those from Connecticut under General Putnam are on Prospect Hill. The Troops in this Town [Cambridge] are entirely of the Massachusetts: The Remainder of the Rhode Island Men, are at Sewalls Farm: Two Regiments of Connecticut & 9 of the Massachusetts are at Roxbury. The Residue of the Army to the Number of about 700 are posted in several small Towns along the Coast to prevent the Depredations of the Enemy.[9]

Washington declared that given all of the challenges the army faced, “We are as well secured as could be expected in so short a Time.”[10] He reported that the lack of tents forced many of the troops to remain in buildings scattered about Cambridge and Roxbury and asked if more tents might be sent from Philadelphia so that he could bring the army into two distinct camps. “I am well assured, that besides greater Expedition & Activity in Case of Alarm, it would highly conduce to Health & Discipline,” he reasoned.[11] He then turned his attention to the appearance of the troops.

I find the Army in general, & the Troops raised in Massachusetts in particular, very deficient in necessary Cloathing. Upon Inquiry there appears no Probability of obtaining any Supplies in this Quarter. And on the best Consideration of this Matter I am able to form, I am of Opinion that a Number of hunting shirts not less than 10,000 would in a great Degree remove this Difficulty in the cheapest & quickest Manner . . . If put in Practice [it] would have a happier Tendency to unite the Men, & abolish those Provincial Distinctions which lead to Jealousy & Dissatisfaction.[12]

He reported that the number of troops with the army was well short of the 30,000 that was originally called for and acknowledged the challenge of introducing proper military discipline to them, but slyly ended the letter with a compliment for the troops.[13]

From the Number of Boys, Deserters, & Negroes which have been listed in the Troops of this Province, I entertain some Doubts whether the Number required can be raised here; and all the General Officers agree that no Dependence can be put on the Militia for a Continuance in Camp, or Regularity and Discipline during the short Time they may stay . . . The Deficiency of Numbers, Discipline & Stores can only lead to this Conclusion, that their Spirit has exceeded their Strength. . . .

It requires no military Skill to judge of the Difficulty of introducing proper Discipline & Subordination into an Army while we have the Enemy in View, & are in daily Expectation of an Attack, but it is of so much Importance that every Effort will be made which Time & Circumstance will admit. In the mean Time I have a sincere Pleasure in observing that there are Materials for a good Army, a great Number of able-bodied Men, active Zealous in the Cause & of unquestionable Courage.[14]

Washington was more candid about his first impression of the army with his brother Samuel nearly three weeks after his arrival. “I came to this place the 2d Instant & found a numerous army of Provincials under very little command, discipline, or order,” he wrote.[15] He addressed the disorder that he found by re-structuring the army into three divisions under Major Generals Artemas Ward, Charles Lee, and Israel Putnam. The troops, which he estimated numbered “between 16 & 18,000,” were kept busy strengthening the fortifications already built and fortifying several other hills previously left unoccupied.[16] Washington confidently declared to his brother that,

I . . . had reason to expect before this, another attack from [the enemy]; but, As we have been incessantly (Sundays not excepted) employed in throwing up Works of defence I rather begin to believe now, that they think it rather a dangerous experiment; and that we shall remain sometime watching the Motions of each other, at the distance of little more than a mile & in full view.[17]

Although General Washington was satisfied with the progress of the earthworks protecting his army, he was less so about the conduct of his troops and officers. About a week before he wrote to his brother, the American commander addressed an awkward situation involving his sentries. Some were communicating with the enemy while on guard duty. Washington addressed this behavior in his general orders of July 15: “Notwithstanding the Orders already given, the General hears with astonishment, that not only Soldiers, but Officers unauthorized, are continually conversing with the Officers and Sentrys of the Enemy.”[18] Washington threatened harsh punishment to anyone who continued to communicate with British sentries and officers.

Musket fire in camp remained a problem as well. Not only did such firings cause alarm and confusion in camp, but it was a waste of something the army had precious little of, ammunition.

Washington announced in early August that

It is with Indignation and Shame, the General observes, that notwithstanding the repeated Orders which have been given to prevent the firing of Guns, in and about Camp; that it is daily and hourly practiced; that contrary to all Orders, straggling Soldiers do still pass the Guards, and fire at a Distance, where there is not the least probability of hurting the enemy, and where no other end is answer’d but to waste Ammunition, expose themselves to the ridicule of the enemy, and keep their own Camps harassed by frequent and continual alarms, to the hurt of every good Soldier, who is thereby disturbed of his natural rest, and will at length never be able to distinguish between a real, and a false alarm. For these reasons, it is in the most preemptory manner forbidden, [that] any person or persons whatsoever, under any pretence . . . pass the out Guards, unless authorized by the Commanding Officer of that part of the lines . . . Any person offending in this particular, will be considered in no other light, than as a common Enemy, and the Guards will have orders to fire upon them as such.[19]

Washington added that regimental commanders were to ensure that their soldiers were “acquainted with Orders to the end, that no one may plead Ignorance, and that all may be apprized of the consequence of disobedience.”[20]

In late August General Washington, still frustrated by the conduct of his troops and particularly many of his officers from Massachusetts, wrote a candid letter to his cousin Lund Washington, who had agreed to manage the general’s estate at Mount Vernon (in conjunction with Mrs. Washington) during the general’s absence.

The People of this Government have obtained a Character which they by no means deserved. Their Officers generally speaking are the most indifferent kind of People I ever saw. I have already broke one Colo. and five Captains for Cowardice & for drawing more Pay & Provisions than they had Men in their Companies . . . . In short they are by no means such Troops, in any respect, as you are led to believe of them from the Accts which are published, but I need not make myself Enemies among them, by this declaration, although it is consistent with truth. I daresay the Men would fight very well (if properly Officered) although they are an exceeding dirty & nasty people.[21]

Washington also expressed his frustration with the army to Richard Henry Lee, a member of the Continental Congress from Virginia.

It is among the most difficult tasks I ever undertook in my life to induce these people to believe that there is, or can be, danger till the Bayonet is pushed at their Breasts; not that it proceeds from any uncommon prowess, but rather from an unaccountable kind of stupidity in the lower class of these people, which believe me prevails but too generally among the Officers of the Massachusetts part of the Army, who are nearer of the same Kidney with the Privates; and adds not a little to my difficulties; as there is no such thing as getting Officers of this stamp to exert themselves in carrying orders into execution—to curry favour with the men (by whom they were chosen, & on whose Smiles possibly they may think they may again rely) seems to be one of the principal objects of their attention.[22]

Washington questioned the method of selecting officers below the rank of generals, which left the decision to the individual colonies. He felt strongly that this resulted in too many inadequate officers who did little to help establish better discipline among the troops.

There has been so many great and capital errors, & abuses to rectify—so many examples to make—& so little Inclination in the Officers of inferior Rank to contribute their aid to accomplish this work, that my life has been nothing else (since I came here) but one continued round of annoyance & fatigue; in short no pecuniary recompense could induce me to undergo what I have, especially as I expect, by shewing so little Countenance to irregularities & publick abuses to render myself very obnoxious to a greater part of these People.[23]

Despite Washington’s frustration with the army, he conveyed to his brother John in mid-September a degree of confidence that the army could stand against the enemy.

Being, in our own opinion at least, very securely Intrenched, and wishing for nothing more than to see the Enemy out of their strong holds, that the dispute may come to an Issue. The inactive state we lye in is exceedingly disagreeable especially as we can see no end to it, having had no advices lately from Great Britain to form a judgement upon . . . Unless the Ministerial Troops in Boston are waiting for reinforcement, I cannot devise what they are staying there after and why (as they affect to despise the Americans) they do not come forth, & put an end to the contest at once.[24]

Washington noted that the British in Boston suffered from a lack of fresh provisions and firewood. “In short, they are from all accts suffering all the Inconveniencies of a Siege,” despite having access to the sea.[25] Yet, they remained inactive in the city, seemingly content to tear down buildings for firewood and survive on salted rations from the navy.

General Washington had to look elsewhere for any meaningful action; to the wilderness of Maine, where he sent an expedition under Col. Benedict Arnold on a mission against Quebec, and to Canada, where another American army under Gen. Richard Montgomery, marched from north from Fort Ticonderoga in New York against the British in St. Jeans and Montreal.

While dramatic events occurred on both those fronts, little seemed to change concerning the siege of Boston. Upon the horizon, however, with the approach of a new year, loomed perhaps the biggest challenge of all for General Washington, raising a new army to replace those who returned home when their enlistments expired on the first of December and January. To do this, and maintain the siege in the face of a powerful enemy, seemed an impossible task, yet one that rested upon General Washington’s shoulders. The first of his eight winters at war promised to be even more challenging than his summer of struggle with the new continental army.

[1] Philander D. Chase, ed., “General Washington to Lund Washington, August 20, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 1 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985), 335-336.

[2] “General Washington to Martha Washington, June 18, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:3-4.

[3] “General Washington to John Augustine Washington, June 20, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:20.

[4] “General Washington to Burwell Bassett, June 19, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:12-14.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Address from the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to General Washington, July 3, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:52.

[7] Ibid., 53.

[8] “General Orders, July 4, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:54.

[9] “General Washington to John Hancock, II Letter Sent, July 10-11, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:85-86.

[10] Ibid., 86.

[11] Ibid., 87

[12] Ibid., 88-89.

[13] Ibid. 90-91.

[14] Ibid., 90-91.

[15] “General Washington to Samuel Washington, July 20, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:135.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “General Orders, July 15, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:119.

[19] “General Orders, August 4, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:218-219.

[20] Ibid., 219.

[21] “General Washington to Lund Washington, August 20, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:335-336.

[22] “General Washington to Richard Henry Lee, August 29, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:372.

[23] Ibid., 375.

[24] “General Washington to John Augustine Washington, September 10, 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1:447.

[25] Ibid.

2 Comments

Very good and interesting piece. Washington certainly faced a mammoth and unenviable task. Thank you. But to say that Washington did not want the command begs the question of why he was parading around the Continental Congress in full uniform….

Hello John. Just conveying what General Washington said himself in several of his most personal letters after his appointment. Sure, one can conclude that by wearing his uniform to Congress, Washington was posturing for the job. But I think such views are affected by hindsight about his appointment and service. I think at the time, appointing a Virginian to command a New England army (with ten companies of riflemen from PA, VA, and MD) was a pretty bold and surprising move. Aside from wearing his uniform to Congress, which could just as easily been a symbolic gesture on his part to express support for the brave men of New England, what other evidence is there that Washington actively sought the appointment? I know of none, but he says in several letters that he wished to avoid it. Call me a biased Virginian, but I take his Excellency at his word.