By March 1782 Loyalist Col. David Fanning had been a thorn in the side of Patriot forces for some time. Fanning’s perpetually violent methods were well known to Patriots throughout North Carolina, as was his desire to visit retribution upon previous foes. But the story of one of his most infamous raids for that revenge has yet to be accurately told. For three days in early March 1782, Colonel Fanning and his small group of Loyalists terrorized Randolph County, North Carolina, leaving several Patriots dead in their own homes and the property of others burned and destroyed. The narrative of the raid, examined and updated here, is a prime example of the open and lawless violence that both Patriots and Loyalists faced in the period after the British surrender at Yorktown in October 1781 and the final peace in 1783.

In the months after Yorktown, large swaths of America were in a de facto state of lawlessness, and though full-scale pitched battles between the British and Continental armies were over, civil war between Loyalists and Patriots remained active in some areas. The beleaguered Continental army offered no reliable protection, particularly in the interior. Local militia units charged with protecting the inhabitants of their districts were in most cases no better. Manpower and supply shortages, infighting among the officer corps, and battle fatigue among the rank and file had plagued and decimated the army and state militia units. None of these ailments had improved after Yorktown; if anything they had worsened.

Confrontations between Patriots and Loyalists persisted, and by March 1782 the situation was perfect for Fanning to strike a blow. Driven by a deep desire for retribution, his violent methods were often combined with the outright destruction of personal property. Patriot forces increasingly viewed him as an innately cruel and unusual military leader, someone modern society would perhaps label as a war criminal. Several overtures by Fanning to make peace had been rebuffed in late 1781 and early 1782. This was not a period of forgiveness, it was one of settling scores, and with his requests to negotiate a peace agreement ignored, and militias hunting him throughout North Carolina, Fanning was ready to begin settling his, and he had plenty.

On the second Sunday in March, Fanning and his men unleashed their “Bloody Sabbath” raid throughout North Carolina. It was in fact a multi-day terror campaign, characterized with the destruction of personal property and the murder of people in their homes. Although the historiography leaves a complicated and messy trail, enough primary and secondary material is available to permit an accurate narrative, though assembling it is a challenging task. It requires a systematic review of the scholarship, tracing its evolution, and reviewing the footnotes and sources of each author against the body of evidence, separating the factual from the inaccurate. Combing the sources chronologically reveals errors often repeated by authors who did not closely scrutinize their source material.

Fanning offered his own version of events in his autobiography, a self-serving work with numerous inaccuracies.[1] The manuscript laid untouched for over seven decades before its publication is 1861, but several of the raid’s earliest chroniclers had access to it, and before the era of professional historians Fanning’s inaccurate claims were weaved into the historiography. Fanning, for his part, openly admitted to several of his atrocities, boasting proudly of Patriots he murdered.[2]

The historian Alexander Gray penned a piece on Fanning’s exploits for the Raleigh Register in September 1847, and historian Archibald D. Murphey did the same in an 1853 edition of North Carolina University Magazine. Murphey’s personal papers were published in 1914 and included several more notations on Fanning’s life.[3] The Reverend, turned amateur historian, E.W. Caruthers published a lengthy work on the history of the state of North Carolina in 1854 that for the first time offered an expanded look at Fanning’s raid. It uniquely included details he pieced together from letters and oral histories gathered during his research. He had access to Fanning’s manuscript as well, and concluded in light of his new information that Fanning’s version was woefully incomplete. Caruthers’ work widely expanded the scholarship of Fanning’s raid and has stood up well to historiographical review.[4]

An extended period passed with minimal growth of the scholarship before modern authors began to address Fanning’s life and the raid. The modern work is, however, limited, and has done little to advance the story. The only legitimate biography of Fanning was offered by John Hairr in 2000, with a revised edition in 2023 under a new title. Neither work offered any updates to the raid’s history.[5] Several other authors and websites have also offered various versions of Fanning’s infamous raid, all with various repeated inaccuracies.[6] The raid’s most complete and analytical review came in articles published within the Journal of the American Revolution by Hershel Parker, offering the clearest examination of events with previous historiography in mind.[7] Finally, the most recent narratives of the Revolution have offered scant coverage, and no attempts to sort out the complicated story of Fanning’s vengeful rampage.[8]

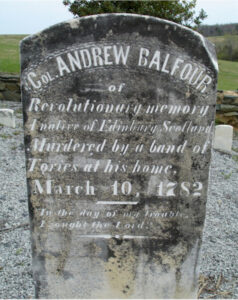

It all began in early 1782 when Fanning tried to reach a truce with Patriot leaders several times, specifically with Col. Andrew Balfour, but all rebuffed him. Fanning’s sincerity towards peace is certainly questionable, and whatever his intentions, the reputation he had earned left no Patriot leader in any mood to negotiate with him. As the spring of 1782 approached his patience was thin, he trusted no one, and no one trusted him.[9]

Fanning wrote that about the 7th of March a small group of Loyalist and Patriot militia had a small run in and exhausted their ammunition without consequence. Afterward, they agreed to seek terms for a truce agreeable to their respective commanders and went their separate ways. Soon after return to his camp, Fanning claimed in his narrative, the answer from the Patriot side came in from Colonel Balfour proclaiming, “there was no resting place for a Tory’s foot upon the earth.”[10] The message was no hollow boast; Balfour put together a detachment with around twenty men and set out to find Fanning. The two were steady adversaries, eager to face off once more, and Fanning quickly took control of the situation and seized the initiative.

The series of events that followed quickly developed into acts of personal retribution against individual Whigs and anyone who got in the way. Balfour’s unit came across Fanning’s on the evening of March 8 while Fanning and a few of his men were gathered at a home where they were “fiddling and dancing.”[11] Fanning’s men spotted them before they could engage and managed to slip away into the nearby woods. They exchanged fire back and forth before separating in the darkness and once more placed distance between them.

Fanning took the opportunity and quickly gathered the rest of his men. They donned newly made matching uniforms and set out after Balfour’s group to “to give them a small scourge.”[12] The first victim was destined to be his arch enemy Colonel Balfour, and it proved to be one of the most infamous murders of the war. Fanning and his men arrived at Balfour’s on the morning of Sunday March 10 to begin the Bloody Sabbath. At this point, stories of the raid have taken differing paths, reconciled by careful review of several little known sources.

The best evidence supports Balfour having been shot by one of Fanning’s men somewhere outside the house, likely struck in one of his arms. Fanning indicated the whole affair was wrapped up quickly, writing that the next round went “through his neck, which put an end to his committing any more ill deeds.”[13] However, there was much more to the story of those hours at Balfour’s home. A letter written by his sister Margaret reveals that after the first shot Balfour retreated into the house where she and his young daughter were. Fanning and his men stormed in, and she described the rest of the events in the letter to her widowed sister-in-law, writing that, “About twenty-five armed ruffians came to the house with the intention to kill my brother. Tibby and I endeavored to prevent them; but it was all in vain. The wretches cut and bruised us both a great deal and dragged us from the dear man then before our eyes. The worthless, base, horrible Fanning shot a bullet into his head.”[14]

According to Margaret Balfour, it was Fanning who personally executed the colonel. In another letter months later, she told his widow that his head was held in her bosom until he died, at which time she and his daughter were dragged from the house and forced to wait outside while Fanning’s men ransacked the home and took everything they pleased.[15] Additional primary sources help confirm the timeline and events at Balfour’s home. Maj. Absalom Tatum wrote to North Carolina Gov. Thomas Burke shortly after that “On Sunday the 11th instant Colonel Balfour, of Randolph, was murdered in the most inhuman manner by Fanning and his party … Colonel Balfour’s sisters and daughters and several other women were wounded and abused in a barbarous manner.”[16]

A year later one of Fanning’s men was prosecuted in criminal court as a participant in Balfour’s murder, and the indictment document adds an additional source concurring with Margaret Balfour and Major Tatum.[17] Tatum misdated the murder to March 11, but clearly meant it as March 10, as he stated it was a Sunday, and all other sources agree that the raid began at Balfour’s house on a Sunday.

Balfour’s murder was only the raid’s beginning. Fanning’s narrative omits details of his next few stops that can be pieced together from other sources. First, they travelled to the home of William Milliken, and with Milliken not home they removed his family from the house and burned his property. Milliken’s son, Benjamin, was home, and they “compelled” him and a man named Joshua Lowe to guide them to the home of militia Col. John Collins.[18] Collins was also not home, and as with Milliken’s, they burned his home and property before moving on. Milliken and Collins were the “several rebel houses” Fanning recorded burning as he travelled from Balfour’s in search of more Patriot victims.[19]

The group next proceeded to the home of another Randolph County militia colonel, John Collier, whose name similarity with Collins has caused occasional confusion in the historiography. Arrival at Collier’s estate was not until after dark on the 10th. Aware he might be targeted; Collier had employed a sentry to watch his home at night. The sentry detected the approach of Fanning’s men and after some verbal exchanges they fired upon him. Some authors include a claim that the musket balls bounced off his tightly woven vest! Whether that detail is exaggerated, legend, or simple falsehood, the night’s narrative remains the same.

Collier heard the shots and awoke. Carruthers recorded that although he had no troops staying with him, Collier yelled out orders for his men to parade to a defense.[20] The clever ruse delayed the advance of Fanning’s men and allowed Collier to mount a horse he had kept ready. He escaped without harm, and Fanning wrote that the escape was so close that several balls passed through Collier’s shirt as he rode away under fire. Afterwards Fanning “took care to destroy the whole of his plantation.”[21]

From Collier’s estate they set out for the home of militia Capt. John Bryant, occasionally named incorrectly by authors as John Bryan.[22] They became lost on the way to Bryant’s, yet another detail regularly confused in the scholarship.[23] They went to the home of a man named Stephen Harlin, described as a Quaker, or “at least an unoffensive kind of man,” and while there, “did not molest him; but compelled his daughters, Betsy and Elsy, to go along and show him the way to Bryant’s house.”[24] When the group reached Bryant’s home that night a dramatic chain of events unfolded.

On arrival they attempted to burst into the house, but the doors were barred well, and Bryant was asleep. The noise woke him and they began a verbal exchange, with Bryant yelling out he did not believe that it was Fanning and his men present. Harlin’s daughters tried to convince him it was indeed Fanning, and implored him to surrender. Bryant asked his fate should he come out, and Fanning replied with an offer of parole. “Damn you and your parole too, I have had one and will never take another!” was Bryant’s reply.[25] He cracked the door open and tried to admit one of the Harlin daughters into the house, but she was pulled back before she could enter and he quickly retreated back inside.

The tension increased with impatient parties on all sides. On Fanning’s order his men set fire to the home with no regard to the occupants still inside. Fanning claimed that once the fire began Bryant changed his tone and asked for it to be put out to spare his wife and home in exchange for his surrender.[26] Caruthers describes Bryant as a “brave but reckless kind of man,” but at this juncture bravery would perhaps have been reckless, and led to the injury of his family, certainly his property, not unreasonable outcomes to a leader such as Fanning. Having held out as long as he could, Bryant stepped outside to give himself up, and once more events and scholarship took a turn.

Fanning declared that Bryant came out with his sword in one hand and his gun cocked and ready in the other, declaring “Here damn you, here I am!” Caruthers describes it much differently, writing that Bryant exited calmly and stated simply, “Gentlemen, I surrender.”[27] Caruthers holds the edge in authenticity over Fanning, but authors have repeatedly used Fanning’s version. The primary sources do not allow for a definitive conclusion on which version of Bryant’s surrender is correct. Both are plausible, and perhaps the truth is a combination of the two, or perhaps neither has any truth.

The style of Bryant’s exit, or his words as he did so, do not change the outcome. When he stepped out onto the porch he was shot and fell back into the arms of his wife who had followed him out. As she caught his fall one of Fanning’s men stepped onto the porch and shot him in the head. All accounts agree on that point. Whether the killing was provoked by Bryant, or was a cold-blooded murder by Fanning or one of his men can never be known with certainty. Fanning was certainly no stranger to such acts, yet, if Bryant did exit his home in an aggressive manner it was Fanning’s revenge-seeking posse that brought him the reason to do so. Justified or not, the events on Bryant’s porch befit the raid to that point, a chaotic scene ending in the death of a Patriot leader in his own home and in front of his family.

The group rested for a period at Bryant’s home, and as the sun rose made their way to the Randolph County Courthouse where they hoped to disrupt, or worse, an election for the state assembly taking place that day. However, word of the raid had spread throughout the county, and to Fanning’s disappointment no one showed up to the courthouse. In a bloodless victory for Fanning, the election was postponed. Leaving the courthouse, the raiders traveled to the home of Patriot officer Maj. Thomas Dougan, where once more Fanning proudly exclaimed, “I destroyed all his property; and all the rebel officer’s property in the settlement for the distance of forty miles.”[28] The identities of additional victims within the forty mile distance who suffered the destruction of their property is not yet known; perhaps there were no additional victims, and Fanning’s statement is summative of the previous few days of his raid.

The carnage included one more death in need of explanation. Burning rebel property was not the only activity for Fanning’s men during their travels from the courthouse to Major Dougan’s. Fanning wrote, “On our way I catched a commissary from Salisbury who had some of my men prisoners and almost perished them and wanted to hang some of them.”[29] They took the man captive and summarily decided to hang him. The scholarship is unanimous that Fanning’s group hanged a man – it is the name of the victim that is surrounded by error and confusion. Fanning, who typically boasted of his victims, provided no name, and not enough detail to help identify the Bloody Sabbath raid’s final casualty.

The first known account of the incident is contained in the Papers of Archibald Murphey. Archibald D. Murphey an early historian of North Carolina, was well connected through family and his government positions to survivors or early ancestors of those directly involved with Fanning’s raid. According to Murphey, the man hanged that day was Daniel Clifton.[30] When Lindley S. Butler edited his version of Fanning’s Narrative he concurred, and provided detailed footnotes and the sources he used to explain his conclusion, which on review pass historical standards for accuracy.[31] For this part of Fanning’s raid the evidence reveals the early historiography was correct, and later authors working from inaccurate sources created confusion with additional names.

One name several authors repeat as the final victim is Archibald Murphey, with some authors labeling him a colonel, others a sergeant. Citations attribute this identification to the published works of J.D. Lewis and Patrick O’Kelley. Lt. Col. Archibald Murphey was the father of Archibald D. Murphey, whose account is cited above. It seems highly improbable he would have covered the raid and not mentioned his own father as a victim of it; moreover, Colonel Murphey lived until 1817.[32]

The evidence confirms Daniel Clifton as the victim, and his hanging ended the raid. As word of the raid had spread, local militia gathered quickly and an active manhunt for Fanning’s posse was soon underway. Several days of rain in the area slowed the efforts of the militia, and Fanning, as he always had, slipped away and was gone.

The Bloody Sabbath raid holds as one of the war’s more infamous events of 1782. The raid resulted in the documented murder of three Patriots and the destruction of the estates of four others. The chronology of the Bloody Sabbath is also clear. Colonel Balfour’s murder began the raid and William Milliken’s property was burned shortly after. The properties of Colonel Collins and Colonel Collier followed, and that evening Colonel Bryant was killed on his porch. The following morning Major Dougan’s property was burned, fear stopped the voting at the Randolph County courthouse, and in the afternoon of that final day Daniel Clifton was caught and hanged by Fanning’s group.

Months after the victory at Yorktown, Patriots and Loyalists were still vulnerable to the terrors of war. Nowhere was immune to threats of violence, but the Carolinas were particularly affected in what was no less than a civil war playing out at an accelerated pace. Many used the lawless period and uncertainty to visit retribution upon others. There can be no doubt both Patriots and Loyalists participated in these activities, and both sides committed atrocities. The months after Yorktown were in some ways, and in some areas, the most violent of the war.

[1] David Fanning, The Narrative of Colonel David Fanning, (A Tory in the Revolutionary War With Great Britain) Giving an Account of His Adventures in North Carolina, from 1775 to 1783, (1861, reprint, Alpha Editions, 2019).

[2] There have been several more editions of Fanning’s memoir, with each release containing introductions by the latest scholar to review the work. The definitive edition (other than the original) is the annotated version edited by Lindley S. Butler released in 1981. Several other editions were used by the author for this study and are cited when necessary as they relate to analysis of the raid.

[3] Alexander Gray, Untitled letter on Colonel David Fanning’s Bloody Sabbath Raid, Raleigh Register, September 11, 1847; Archibald D. Murphey, “North Carolina: Civil War of 1781-82, Col. David Fanning,” University of North Carolina Magazine, March, 1853, 72-86; Archibald D. Murphey, The Papers of Archibald D. Murphey, vol. 2, ed. William Henry Hoyt (Raleigh: Publications of the North Carolina Historical Commission, 1914), www.carolana.com/NC/eBooks/The_Papers_of_Archibald_D_Murphey_Volume_II_1914.pdf.

[4] E.W. Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents: Sketches of Character, Chiefly in the Old North State, 2 vols., ed. Jack E. Fryar Jr. (1854, reprint, Dram Tree Books, 2010).

[5] John Hairr, Colonel David Fanning: The Adventures of a Carolina Loyalist (Erwin, NC: Averasboro Press, 2000); John Hairr, Carolina Loyalist: The Revolutionary War Life of Colonel David Fanning (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company Inc. Publishers, 2023).

[6] These include Patrick O’Kelley, Nothing But Blood and Slaughter: The Revolutionary War in the Carolinas, vol. 4, 1782 (Lillington, NC: Blue House Tavern Press, 2005), and J.D. Lewis, “Colonel David Fanning,” www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/loyalist_leaders_nc_david_fanning.html.

[7] Hershel Parker, “Fanning’s Bloody Sabbath As Traced By Alexander Gray,” Journal of the American Revolution, May 4, 2015, https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/05/fannings-bloody-sabbath-alexander-gray/; Hershel Parker, “Absolving David Fanning-From Dreck to Rumph,” Journal of the American Revolution, November 24, 2015, allthingsliberty.com/2015/11/absolving-david-fanning-from-dreck-to-rumph/.

[8] This includes John Buchannan, The Road to Charleston: Nathanael Greene and the American Revolution (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001), which covers the raid with one sentence, Don Glickstein, After Yorktown: The Final Struggle for American Independence (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2016) which covers the raid with less than one paragraph, and Kenneth Scarlett, Victory Day: Winning American Independence, The Defeat of the British Southern Strategy (Charleston: Palmetto Publishing, 2022), which makes no mention of the raid at all.

[9] Fanning, Narrative, 46.

[10] Ibid, 50.

[11] Ibid. Fanning and some historians misdate this as March 10, but this action was the evening of March 8 to align with Fanning’s own timeline of a day between his first contact with Balfour’s party and his attack on Balfour at his estate. This can be confirmed by the solid evidence that properly dates the attack on Balfour at his home to Sunday March 10.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid, 51.

[14] Margaret Balfour to Eliza Balfour, September 12, 1782, in Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents, 1:172.

[15] Margeret Balfour to Eliza Balfour, August 17, 1783, and September 12, 1782, in Caruthers, Revolutionary Sketches, 1:172-175.

[16] Absalom Tatum to Thomas Burke, March 20, 1782, in Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 16:244-45, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr16-0068.

[17] Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents, 1:175.

[18] Ibid, 172.

[19] Fanning, Narrative, 51.

[20] Carruthers, Revolutionary Incidents, 1:143.

[21] Fanning, Narrative, 51.

[22] This includes O’Kelley in Nothing But Blood and Slaughter vol. 4, which modern historians have often referenced without scrutiny; he appears to have accepted Fanning’s spelling.

[23] Some sources omit this detail or incorrectly narrate what occurred. O’Kelley, for example, omits the details of the group becoming lost and instead writes that “Fanning talked both of Bryan’s daughters into taking him to their father.” Nothing But Blood and Slaughter, 4:42. Caruthers provides the more trustworthy narrative of the chain of events and his sources are listed as firsthand testimony by older survivors, in this case a man named Isaac Farlow. This author has judged the work of Caruthers as more reliable for the entirety of Fanning’s raid, and other 1782 events, as the work of O’Kelley and J.D. Lewis contain numerous inaccuracies. On many occasions both of their works contain the same exact text with no changes, meaning at least one of them used the work of the other in full.

[24] Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents, 1:143.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Fanning, Narrative, 51.

[27] Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents, 1:144.

[28] Fanning, Narrative, 51-52.

[29] Ibid, 52.

[30] Murphey, Papers, 2:398.

[31] David Fanning, The Narrative of Colonel David Fanning, ed. Lindley S. Butler (Davidson, NC: Briarpatch Press, 1981), 73.

[32] Caswell County Genealogy Society, caswellcountync.org/getperson.php?personID=I3447&tree=tree1.

Recent Articles

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

Recent Comments

"The 100 Best American..."

I would suggest you put two books on this list 1. Killing...

"Dr. James Craik and..."

Eugene Ginchereau MD. FACP asked for hard evidence that James Craik attended...

"The Monmouth County Gaol..."

Insurrectionist is defined as a person who participates in an armed uprising,...