Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City exhibit at the American Philosophical Society (founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1743) positions the historic city as the most consistently politically engaged throughout the war. While New York was occupied by the British for a large portion of the war and Boston saw action at the onset and beginning of the war, Philadelphia often found itself in the middle of the action. While most know the city as home of the Continental Congress and Benjamin Franklin, the APS exhibit showcases the ordinary citizens, merchants, and Quakers who navigated day-to-day life both in support of, and in opposition to, the American Revolution. As described in the APS catalog, “the exhibition is at once a testament to Philadelphia’s central place in the struggle for independence and a testament to the enduring collaborative spirit of Philadelphians” (page 6). Collaboration among the those in power, ordinary citizens, and marginalized peoples exemplifies the early role and importance of diversity in the city’s political engagement and growth.

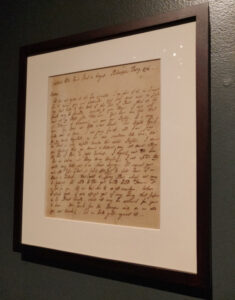

While Philadelphia’s Quaker community prevented the city from being as violent or incendiary as Boston, there were Quakers on all sides of the conflict. The APS exhibit includes diaries from Quaker women Sarah Logan Fisher and Elizabeth Drinker, whose husbands were arrested for not swearing loyalty to the new government. The exhibit also features James Pemberton’s 1775 Quaker Testimony Document affirming the neutrality and pacifism of the religious community.

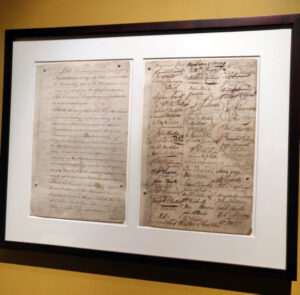

A Revolutionary City spotlights myriad perspectives of women and marginalized groups. Remarkably, the city’s October 1765 Non-Importation Agreement opposing the Stamp Act was signed by six women, one of them an Irish linen shop owner. The collection also includes an extraordinary speech to Congress by Lenape-Delaware leader White Eyes, Koquethagechton, in which he affirmed accord with the colonial government by proclaiming that the Congress had “done well in putting fresh Earth to the roots of the Tree of Peace, that so its growth may be cherished, Agreeable to your advice, I will set down all my people under the Tree.” White Eyes was not the only marginalized person to address congress or Continental representatives, as Quaker wives—including Elizabeth Drinker, directly petitioned Washington and Congress in 1778 for return of their exiled men.

The most compelling components of the exhibit are the artifacts of social; the artfully crafted trade cards advertising local businesses, colorful folk art “fraktur” adorning German birth certifcates, a newspaper rife with interesting nuggets of daily life, and a stunning white and red handkerchief deocrated with iconic revolutionary design elements. Through these unique objects of citizens’ everyday life are we able to truly connect with and humanize the conflict. Whether exhibit attendees pore over old maps of Philadelphia to compare to its modern version, or imagine themselves writing in their journals about tumultous current events like Elizabeth Drinker, viewers will no doubt find something tangible to connect them with the past.

When asked what artifacts, from a treasure trove of records and collections, narrowly missed the cut for the exhibit, APS Museum Librarian and Director Michelle Craig McDonald described a series of letters regarding infamous traitor Benedict Arnold and his Philadelphian wife Peggy Shippen. Pondering what interesting tidbits such documents hold, one leaves the exhibit speculating over what other historic gems, such as enlistment papers found in the wall of an Old City home that are displayed in the exhibit, are waiting to be uncovered.

Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City is on view at American Philosophical Society’s Library and Museum at 104 S. 5th St. Philadelphia, Thursdays through Sundays 10 AM – 5 PM, until December 28, 2025. Those wishing to pursue further research on eighteenth-century Philadelphia can visit therevolutionarycity.org, a portal providing “a single entry point to a documentary archive drawn from different institutions and from collections of variable accessibility” (p. 31). The Revolutionary City: A Portal to the Nation’s Founding, also known as Rev City, continues an ongoing effort to reach audiences “whose forebears have often been sidelined or ignored in earlier histories of the American Revolution” (p. 31) such as women, enslaved people, free Africans, and Indigenous people.

Recent Articles

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...