Joseph Warren was the embodiment of the American colonists’ struggle to secure their rights. In 1775 he was a widowed father of four young children and an esteemed Boston physician. He served as chairman of the Committee of Safety and president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. He authored the Suffolk Resolves, which was unanimously endorsed by the First Continental Congress. Warren called the militia to confront the British in Lexington and Concord then worked tirelessly to bring military and governmental order out of chaos in the weeks leading to his ultimate sacrifice on Breed’s Hill. He was the essence of Liberty.

Early scholars laid the foundation in presenting Warren’s life by adhering to the historical record and circumstances. Contemporary writers purported Warren’s personal life using as their source a ledger and letters previously unknown. Allegations based upon this documentation suggest Warren had intimate relationships with two women. The first, Sally Edwards, was pregnant and unwed. The second, Mercy Scollay, was nanny to Warren’s children. These inferences failed to relate the entirety of the letters and historical circumstances surrounding these associations.[1]

Early biographers Richard Frothingham and John Cary made no mention of Sally Edwards. In regard to Mercy Scollay, Frothingham stated, “Warren was betrothed to this lady for a second wife.” His cited documentation was “Loring’s Orators, 49,” but James Spear Loring’s book gave no citation for his statement of betrothal.[2] Cary expanded on the legend, citing a letter from Scollay to John Hancock.[3]

Contemporary biographer Samuel Forman offered conjectures into Warren’s personal life through the accounts of Edwards found in the medical ledger and diary of another physician and Scollay’s letters.[4] From these, Forman inferred that Warren fathered Edwards’ child, and fictionalized brief implications made by earlier biographers of Warren’s betrothal to Scollay.

In Bunker Hill, Nathaniel Philbrick presented Warren as the protagonist. Philbrick noted two conversations with Forman regarding Warren’s relationship to Edwards.[5] Philbrick adhered to Forman’s view of Warren’s betrothal to Scollay.

Sally Edwards

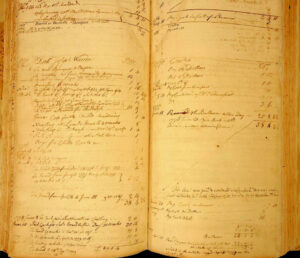

Little is known about Sally Edwards—and less of her association with Warren. He arranged medical care and lodging for her with his friend and colleague Dr. Nathaniel Ames of Dedham. On April 8, 1775, Ames paid a visit to Warren. Ames then created an account in his medical ledger under the heading, “Doctr Joseph Warren.” A fee is entered on April 8 “for “two Journeys to Boston.” On April 10, Ames entered another fee under the same account and identified the fee, “For boarding his fair incognita pregnans.” A diary entry on May 11 reads, “Dr. Warren here.” On June 28, Ames entered a fee for medical services in the Warren account “To deliver her of daughter.” In November, Ames charged a fee for a “gauze cap for the child’s christening.” Various fees were entered by Ames for boarding this woman and her child, and the cost of a wet nurse.[6] Ames’ ledger did not clearly identify the patient. It was through Ames’ diary, transcribed by Robert Brand Hanson, that the connection to Sally Edwards was made. On May 12, 1776, Ames wrote, “Sall Edwards left my house having made much mischief in it.” Hanson noted that in one entry to the “Doctr Joseph Warren” account, Ames wrote next to the payment, “for Sal’s board.” This notation coupled with the charge listed in the ledger for a christening cap for the baby in November 1775, encouraged Hanson to check Dedham church records. He discovered Edwards had her daughter baptized on November 19. The last mention in Ames’ ledger of fees for the care of Edward’s child was in 1779.[7]

This is the extent of Warren’s documented association to Edwards.

Forman’s narrative of Warren’s paternity was, “Joseph Warren organized the obstetrical care for Edwards, a pregnant teen, in early April of 1775 . . . Warren’s close identification with the proceedings, and posthumous continuation of charges to his account suggest but do not prove Joseph’s paternity.”[8]

Though Ames’ documentation offers no insight into Edwards’ age, Forman identified her as a “teen.” No other consideration was given by Forman as to the many possibilities for Edwards’ plight. In the autumn of 1774, when Edwards would have conceived, there were approximately 3,000 British soldiers in Boston. The town’s population was about 16,000. The ratio was one soldier to every five residents.[9] Might Edwards have been a victim of rape? Could she have been impregnated through a consensual encounter after which marriage was not possible? Regardless of the circumstances of her being impregnated, in colonial Boston the birth of a child out of wedlock would be considered disgraceful. Edwards and her family would likely be shunned. Her probability of marriage to a decent man would be lessened. Perhaps Warren never met Edwards, but simply made arrangements for her care.

Philbrick enlarged Forman’s narrative on Edwards. Though he wrote, “There is also the possibility that Sally Edwards had become pregnant by another man, and that Warren was providing her with a discreet safe haven,” Philbrick’s next sentence was, “In all likelihood, however, in mid-to late September 1774, when Warren was caught up in the excitement of the Powder Alarm and the Suffolk Resolves, he got a young woman named Sally Edwards pregnant.” Philbrick further implied (acknowledging Forman’s support) that this was probably the Sally Edwards who would marry Paul Revere’s eldest son in 1782. Philbrick goes on to suggest, with no documentation, that Edwards was a nanny to the Warren children.[10]

An account presented by Warren’s nephew, Dr. Edward Warren, was referenced by Forman and Philbrick to support their premise of Warren fathering Edwards’ child:

I have attended a lady who was born in Dedham on the 17th of June 1775. Dr. Joseph Warren was engaged to attend her mother in her confinement. It is stated that he visited her on that morning, and finding she had no immediate occasion for his services, told her that he must go to Charlestown to get a shot at the British, and he would return to her in season.[11]

Based on this account, Forman and Philbrick offer the possibility that Warren went to check on Edwards before going to Breed’s Hill. Forman wrote, “If Joseph were the father . . . He would have never met his fifth child.” Philbrick stated, “We’ll never know for sure whether or not Warren visited Sally Edwards on June 17, but we do know that Dr. Nathaniel Ames delivered her a baby girl, which meant that Edward Warren’s patient might have been Joseph Warren’s illegitimate daughter.”[12] Though Forman and Philbrick use Edward Warren’s account to favor their narrative, neither acknowledged that the woman gave the specific date of her birth as June 17, 1775. Instead, Forman’s gives June 29, 1775 as the date Edwards delivered, while Philbrick stated that Edwards gave birth “eleven days after the battle.”[13] Of note is that Ames made no mention in his diary of Joseph Warren visiting on this momentous day.

The Watertown Historical Society has a letter stating that Warren did attend a laboring woman in Newton in the early morning hours of June 17. The New England Historical and Genealogical Register from 1871 supports this: “Here General Warren rested on his way to that battle in which he lost his life, riding down from Newton—where he had been engaged the previous night in professional occupation in a case of nativity.[14]

Is it reasonable that as president of the Provincial Congress and chairman of the Committee of Safety—on the morning of a major battle in which he intended to participate—Warren decided to check on Edwards in Dedham even though Ames was presiding over her care? From the Newton/Watertown area to Dedham is about twelve miles. It would take approximately one hour to travel this distance at a canter on horseback. Did Warren then travel fifteen miles from Dedham to Cambridge? Would Warren purposely tie up two hours on such a crucial day to make an unnecessary trip to Dedham? This would not negate the story of Edward Warren’s patient. Rather than Edward Warren’s patient being the daughter of Sally Edwards, might she have been the daughter of the woman in Newton?

On the morning of June 17, Warren presided over the meeting of the Committee of Safety in Cambridge.[15] Dr. David Townsend stated he found Warren in Cambridge that afternoon where he was resting in an attempt to alleviate a headache.[16] Philbrick stated that Forman shared with him in, “a personal communication” that Townsend may have been complicit in a lie to conceal Warren’s visit to Edwards on June 17 by falsely stating he was with Warren that day. Philbrick claims that Forman said Townsend was, “covering for Warren, who maybe did go to Dedham that morning.”[17] The problem with this theory is that Townsend said he saw Warren in the afternoon; he therefore was not “covering for” Warren’s whereabouts on that morning. To further undo this conjecture, as aforementioned, Warren took his position as chairman at the morning meeting of the Committee of Safety in Cambridge.[18]

Multiple females named Sally Edwards resided in and around Boston in 1775. Philbrick and Forman focused on the one who would eventually marry the son of Paul Revere. They “identified” her, but offered no identity—no background, which was readily available. This Sally was the daughter of Dolin and Rebecca Edwards. She was baptized on September 20, 1761. Her father was a mastmaker. Sally was the second of five children. Her mother died in 1771. Dolin died in 1773.[19] If she was impregnated in 1774, she may have just turned thirteen. In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, legal guardianship was required until the age of fourteen. Sally, by law, was a minor—a child. Given her young age, her probable vulnerable mental state following the death of her parents, and the colony on the brink of war, all scenarios of her being impregnated are grievous.[20] Why would Philbrick and Forman make the inferential leap of Warren taking sexual advantage of a child rather than offer consideration to numerous other scenarios? Forman states on his website, “The young doctor may have been attracted to teenagers. His first spouse was barely seventeen at marriage . . . Sally Edwards, a female whose obstetrical care he arranged secretly in 1775, may well have been an underage teen.”[21] Forman hints that Warren was a sexual predator, ignoring the fact that women frequently married at age seventeen in Colonial America and not mentioning Warren was not much older! Philbrick refers to Edwards as Warren’s mistress: “He left behind a fiancée (one of his patients) and a mistress he’d recently impregnated.” The word “mistress” implies the sexual relationship was consensual. A child under the age of legal majority cannot consent.[22]

Dolin Edwards’ brother Robert also had a daughter named Sally born in 1761. She, too, would have been thirteen in 1775.[23] There was a third Sally Edwards in Boston who was seventeen in 1775. She was the daughter of Edward and Elisabeth Edwards, and Warren was physician to this family. Might he have simply been assisting his patient?[24]

Philbrick and Forman suggest that Warren put Edwards in the care of Ames to hide his secret. They further imply that his payments to this account indicate his paternity.[25] Could there be other explanations for Warren placing Edwards with Ames? Ames owned an inn. Like Warren, Ames had many obstetrical cases in his practice, including several unwed patients. Some, like Edwards, were placed with him by other physicians. Are we to assume that these physicians impregnated the women put in Ames’s care, or might it be that Ames offered a safe and discreet haven for unwed women? Whether Edwards was the thirteen-year-old or Warren’s seventeen-year-old patient, would he not want her in the care of a physician competent in obstetrics and away from the complexities, prying eyes, and subsequent condemnation of those in Boston?

Forman made an undocumented claim on his website that the payments to Ames for Edwards and her baby came from Warren’s estate.[26] Did Warren use his own money to cover the charges for Edwards and her baby? According to the Ames ledger, payments were made by Warren and his former apprentices David Townsend and William Eustis.[27] The payments, though made by them, do not determine that the money came from any of these physicians. Perhaps the family of Edwards—or the actual father of the child—gave Warren, Townsend, and Eustis the money to pay the bill. If this was the Sally Edwards that married Paul Revere’s son, might the younger Revere have been the father? Warren and Revere were intimate friends.

Mercy Scollay

In 2018, Christian Di Spigna authored a fourth biography on Warren. Although he offered a short dissent of Warren’s supposed paternity to Edwards’ child, he, like Forman and Philbrick, amplified the legendary narrative of betrothal between Mercy Scollay and Warren.[28]

What is known of Warren’s association with Scollay? Warren was physician to the Scollay family. Mercy Scollay made numerous medical visits and was always charged.[29] She was thirty-four years old in 1775, never married, and lived with her parents. She used a crutch, indicating a physical disability.[30] In the spring of 1775, with news of British reinforcements enroute, many Whig families left Boston. Scollay’s parents remained. Warren made plans with Dr. Elijah Dix, a colleague in Worcester, to place his children under Dix’s care, and Scollay accompanied the children as nanny.[31]

Following Warren’s death, his mother went to Worcester to see her grandchildren. Can there be any doubt that Mary Warren and her remaining sons were grieving and distressed? Warren died intestate. The immediate needs and responsibility of his children, possessions, and debt would fall upon them. After this visit, Scollay publicly claimed custody of the Warren orphans. The first known reference is in a letter she wrote to Dr. Dix on August 17, 1775: “I’ve seen the two Mr Adamses Mr Hancock and Dr Cooper but find nothing can be done respecting the children till a Judge is appointed and I cannot hold them one moment after the relations claim their right.”[32]

Scollay never stated in her letters that she was betrothed to Warren. His mother and brothers had no knowledge of Joseph being romantically involved or giving her custody of his children. There is no historical reference from Scollay’s family or Warren’s friends validating the claim of betrothal—including Warren’s minister, Dr. Samuel Cooper, who was in communication with Warren until his death.[33] An entry in Cooper’s diary made the day after Scollay’s letter was written reads, “Mercy Scollay and General Warren’s little Daughters lodg’d with us.” Though he had frequent access to Warren up until his death, Cooper did not imply any relationship between Warren and Scollay.[34]

Forman claimed that while at a social gathering in 1774 Warren flirtatiously challenged Scollay to write a satire on the female love of dress. In reality, Mercy Otis Warren wrote the satire.[35] Forman disregarded Mercy Otis Warren’s authorship and put forth that Joseph Warren, through this imagined flirtatious challenge, publicly displayed a romantic interest in Scollay.[36]

Di Spigna claimed that the tale of two windowpanes are proof of Warren’s betrothal to Scollay, writing that Scollay “etched her name on a glass windowpane with the diamond ring Warren gave her—a permanent testament to what had once existed between the engaged couple.” And that Warren “had engraved his own name on a window in the old Marshal Fowle house, just prior to his death on the battlefield.” There is no evidence of either Warren or Scollay having had such a ring, nor of the existence of these windowpanes.[37]

Forman and Philbrick asserted that Warren’s reference to Scollay as “family” in a letter dated April 10, 1775, solidifies a status of betrothal: “my children & family I hope will arrive at Worcester by next Thursday Night.”[38] In this letter, Warren clearly separates “my children” from “& family.” The word “family” was frequently used to describe an entourage; Warren’s use of the word does not imply that Scollay was anything more than the nanny.[39]

In the five years following Joseph Warren’s death, Mary Scollay waged a persistent campaign to obtain custody of his children, including a letter to John Hancock written on May 21, 1776. As president of the Continental Congress, Hancock was under enormous stress. After five pages of dramatizing her concerns about the children’s welfare, Scollay wound down her letter with, “nothing I should think too hard a task for the service of those dear Children and look on myself religiously bound by the promises I made my Friend that in case he fell a victim to the rage of Power I would be the Protecteress of his little offspring.” Did Scollay really make such promises? If so, were they made prior to her accompanying the children to Worcester, to assure Warren she would be a responsible nanny? She failed to relate Warren’s response, if there was one. Scollay not only involved Hancock through this letter, but requested that he share it with Samuel Adams and John Adams: “ask their advice in conjunction with yours.” There is no known response from Hancock.

Loring, Frothingham, Edward Warren, and Cary seemingly based their portrayal of betrothal to Warren on Scollay’s written account to Hancock claiming promises made to Warren. Forman, Philbrick, and Di Spigna had full access to Scollay’s letters, none of which suggest betrothal, yet they adhere to her unsubstantiated claims and disregard her schemes to obtain custody, thus negating the extenuating circumstances of the times and emotional struggle of the Warren family. In doing this, they present Scollay—not the Warren family and the children themselves—as the victim.

“Within a year after the death of [Joseph] Warren, it was resolved, by the Continental Congress, that his eldest son should be educated at the public expense; and two or three years later, it was further resolved that public provision should be made for the education of the other children, until the youngest should be of age.”[40] It was further resolved by Congress that the half-pay of a general officer be granted for the children’s care from the time of their father’s death and continue until the youngest child “shall be of age.”[41] Credit for Congress’s resolutions for the education and financial care of the Warren children in both Di Spigna and Forman’s accounts is given to Scollay’s supposed influence and persistence. What was not recognized is that the demands on Congress were colossal. Joseph Warren’s close friends presented the resolutions when the time was appropriate.

The authors of recent books on Joseph Warren seemingly neglected to honor the historical record. Scollay was presented, with no supporting documentation, as being betrothed to Warren, having rightful claim to his children, and having gained from Congress financial stability for the orphans.[42] Little consideration was given by these authors to the Warren brothers’ concern that Scollay may have been using the children to obtain a family of her own. The portrayal of Warren irresponsibly placing his children in the middle of this strife and making them the obligation of a woman with no means of support paints a picture of a negligent parent and callous man. That he would hold back such significant information as betrothal from his mother and brothers implies a sense of disrespect and cruelty.

In the case of Sally Edwards, minimal documentation within the medical ledger of Ames, with no regard to the historical setting or significance of the time, was used to propose a derogatory and disturbing narrative. The casual attitude presented in the relationship of Warren to Edwards depicts a child as a consenting sexual partner rather than a victim of the physical and emotional scars such a criminal act and subsequent pregnancy would inflict.

Early Warren biographers Frothingham and Cary lamented, but accepted, what they considered a lack of personal information pertaining to Dr. Joseph Warren.[43] Forman, Philbrick, and Di Spigna attempted to fill this gap. The manner in which they presented new material pertaining to Warren’s medical practice and private life did not warrant the type of inferential leaps made. Did they not realize that the outcome of their pursuit came at the cost of a good man’s reputation? The responsibility of all historians is to introduce their subject through accountability to historical fact and circumstances. Neglect to do so in contemporary accounts of Joseph Warren have put at issue the character of this exemplary man.

[1] Nathaniel Ames, Ledger Book 1765-1822, Dedham Historical Society, 100; Mercy Scollay, Mercy Scollay Papers, 1775-1824, History Cambridge, Cambridge, MA.

[2] Richard Frothingham, Life and Times of Joseph Warren (Little, Brown & company, 1865), 543; James Spear Loring, Hundred Boston Orators (John P. Jewett and Company, 1853), 49.

[3] John Cary, Joseph Warren: Physician, Politician, Patriot (University of Illinois Press, 1964), 217.

[4] Samul Forman, Dr. Joseph Warren: The Boston Tea Party, Bunker Hill, and the Birth of American Liberty (Pelican Publishing Company, 2012).

[5] Nathaniel Philbrick, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution (Viking, 2013), xvi, 319-320n, 340n.

[6] Ames, Ledger Book, 100. Robert Brand Hanson, ed. The Diary of Dr. Nathaniel Ames of Dedham, Massachusetts, 1758-1822 (Picton Press, 1998).

[7] Ames, Ledger, 100; Hanson, Diary, 278, 280, 307. Massachusetts Vital Records, 1620-1850, Volume: Dedham Church Records, 211.

[8] Forman, Dr. Joseph Warren, 185.

[9] Michelle Snidal, Rape in Revolutionary America, 1760-1815, B.A. Thesis, University of Lethbridge, 2019, www.coursehero.com/file/220520919/Snidal-Michelle-MA-2021pdf/.

[10] Philbrick, Bunker Hill, 101-102, 320n.

[11] Edward Warren, The Life of John Warren: Surgeon-General During the War of the Revolution (Noyes, Holmes, and Company, 1874), 22. Edward Warren was simply relating the story of a patient. The inference that this could have been Warren’s daughter is solely that of Forman and Philbrick.

[12] Philbrick, Bunker Hill, 216.

[13] Forman, Dr. Joseph Warren, 185; Philbrick, Bunker Hill, 216; Ames, Ledger, 100.

[14] Dr. Bennett F. Davenport to Mr. Chas. F. Fitz, December 12, 1903, Watertown Historical Society, archive.org/details/newenglandhistor1871wate/page/n493/mode/2up?q=warren.

[15] Frothingham, Life and Times, 509-513, Cary, Joseph Warren, 219.

[16] Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, Vol. XVII 1768-1777 (Massachusetts Historical Society, 1975), 442.

[17] Foreman, Dr. Joseph Warren, 185. Philbrick, Bunker Hill, 340n.

[18] Frothingham, Life and Times, 509-513, Cary, Joseph Warren, 219.

[19] “Boston, MA: Church Records, 1630-1895,” The Records of the Churches of Boston, www.americanancestors.org/DB31/rd/7624/108/8720119, 108; Boston, MA: Inhabitants and Estates of the Town of Boston, 1630-1822 (Thwing Collection). Inhabitants and Estates of the Town of Boston, 1630-1800 and The Crooked and Narrow Streets of Boston, 1630-1822. CD-ROM. Boston, Mass: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2001. (Online database, AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014.), Accessed 2024/07/12, www.americanancestors.org/DB530/i/14226/38013809, 7464-7465; Headstone of Rebecca Edwards, Copp’s Hill Burying Ground; Suffolk County, MA: Probate File Papers. Online database. AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2017-2019. (From records supplied by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives. Digitized images provided by FamilySearch.org), www.americanancestors.org/DB2735/i/48699/15461-co3/69572226.

[20] Suffolk County, MA: Probate File Papers, Suffolk cases 16000-17999, 17585:1-3.

[21] Forman, “Sandwiched Between Omens of Discord and Rum, the Infamous Mrs. Loring Announces Marriage Vows,” www.drjosephwarren.com/2014/12/Sandwiched-Between-Omens-of-Discord-and-Rum-the-Infamous-Mrs.-Loring-Announces-Marriage-Vows/.

[22] Tony Horwitz “The True Story of the Battle of Bunker Hill,” Smithsonian, May 2013.

[23] Inhabitants and Estates of the Town of Boston, 1630-1800, 7485.

[24] “Boston, MA: Church Records, 1630-1895; Forman, “Dr. Joseph Warren’s Patients – Alphabetical E-K,” www.drjosephwarren.com/2013/06/dr-joseph-warrens-patients-alphabetical-e-thru-k/.

[25] Nathaniel Ames, Ledger, 100.

[26] Forman, “That Little Vixen is the Instrument of their Malice,” web.archive.org/web/20151016220516/http://www.drjosephwarren.com/2012/08/that-little-vixen-is-the-instrument-of-their-malice/.

[27] Nathaniel Ames, Ledger, 100.

[28] Christian Di Spigna, Founding Marty: The Life and Death of Dr. Joseph Warren, the American Revolution’s Lost Hero (Crown, 2018), 273-274n, 203-208.

[29] Joseph Warren, account book, May 4, 1774-April 1775, John Collins Warren papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[30] Scollay, May 10 and December 10, 1776, Scollay Papers.

[31] Frothingham, Life and Times, 473-475; Joseph Warren to unnamed recipient, April 10, 1775, Christie’s Auction Catalog, June 9, 1999, www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-1522597; Scollay, April 26, 1776, Scollay Papers.

[32] Scollay, August 17, 1775, May 10, July 27, December 9, 1776, May 21, 1777, Scollay Papers. Mercy Scollay to John Hancock, May 21, 1776, 6, Hancock family papers, microfilm reel 2, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[33] Cary, Joseph Warren, 205.

[34] Samuel Cooper, “Diary of Samuel Cooper, 1775-1776,” American Historical Review Vol. VI No. 2 (January 1901).

[35] Mercy Otis Warren, Poems, Dramatic and Miscellaneous (I. Thomas and E. T. Andrews, 1790), 208-212.

[36] Forman, Dr. Joseph Warren, 185-187, 371-375, 411-412.

[37] Di Spigna, Founding Martyr, 203, 285; Reminiscences of Biographical Notices of Twenty-One Members of the Worcester Fire Society (Worcester Fire Society, 1899),, 25; Watertown’s Military History (David Clapp & Son, 1907), 71.

[38] Joseph Warren to unnamed recipient. This letter was photographed in 1999. Its current location is unknown; Forman, Dr. Joseph Warren, 187, 394-395n; Philbrick, Bunker Hill, 112, 321n.

[39] In 1828 the definition of family was, “The collective body of persons who live in one house and under one head or manager; a household, including parents, children and servants.” Noah Webster’s 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language, 5431, archive.org/details/noah-websters-1828-dictionary-ellen-g-white-estate.

[40] Everett, Life of Joseph Warren, 80.

[41] Frothingham, Life and Times, 544.

[42] Forman, Joseph Warren, 371-375; Di Spigna, Founding Martyr, 25.

[43] Cary, Joseph Warren, viii-ix.

2 Comments

It seems there is no way to know the details of the relationship between Joseph Warren and Sally Edwards with certainty. However I would lean toward an intimate relationship, or at least Ames’s belief in an intimate relationship, given his use of the phrase “fair incognita.” Though it means, literally, “beautiful unknown woman,” in the 18th c. it was often used to anonymously describe a secret love.

In 1779 the future George IV wrote to Mary Hamilton, “I now declare that my fair incognita is your dear dear dear Self,” he writes. “Your manners, your sentiments, the tender feelings of your heart, so totally coincide with my ideas, not to mention the many advantages you have in form & person over many other ladies, that I not only highly esteem you, but even love you more than Words or ideas can express.”

A “fair incognita pregnans” to me sounds like a pregnant mistress. Or at least, that Ames suspected this.

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through scholarly analysis combined with emotional intelligence.