The pivotal military events that transpired in the northern theatre of war during the American Revolution are well known. A chronological list of the main ones would include: the failed American invasion of Canada in 1775-76; the British naval victory on Lake Champlain at the Battle of Valcour Island in 1776; the decisive American victory at Saratoga that foiled British plans in 1777; and the brutal raiding by both protagonists on the frontier borders in 1778-1780. By 1781 through to 1783, the defense of Canada had become the British focus in the northern theatre as well as the ongoing but not to be fulfilled aspiration that the republic of Vermont might join the Empire. Fort St. John’s, a post on the Richelieu River between Lake Champlain and Montreal, was directly connected to most of these renowned events.[1] There were also some fascinating but forgotten happenings that took place there. Though they are obscure in the annals of history, they nonetheless were very significant at the time. Two events that fit into this category were the destructive fires that erupted at the fortification in 1780 and 1783.

A Strong Defensive Headquarters and Naval Shipyard

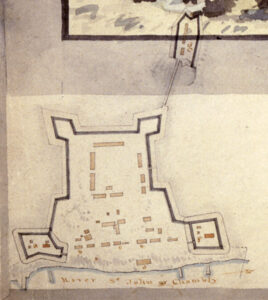

Fort St. John’s strategic location at the head of the St. Jean rapids on the Richelieu River gave its shipping an unimpeded route to Lake Champlain which was the “logical entryway from Canada into the center of the . . . colonies.”[2] Situated on the west side of the river, south of Fort Chambly, north of Ile aux Noix, and approximately twenty-five miles from the American border, was this dominant fortification. In 1775 the fort was anchored at its north and south ends by redoubts positioned six hundred feet apart that were connected by a palisaded trench. In between the redoubts was a naval dockyard. British officer Thomas Anburey vividly described the naval dockyard and fort on November 30, 1776, as follows:

I was much pleased with the place, it having all the appearance of a dock-yard, and of being equally busy. The fleet that was upon the Lake is repairing, as likewise several of the vessels that we took from the Americans; they are laid up in docks, to preserve them from the inclemencies of the winter . . . This place, which is called the key to Canada, when the works are compleated, will be of great strength; there are temporary barracks at present, both for soldiers and artificers. The old barracks, as well as the fort the Americans destroyed when they abandoned the place, were formerly quite surrounded with woods, but are now clear for some distance round. In order that you may form a just idea of this important place, I have enclosed you a drawing of it, representing the two redoubts, with the rope-walk, the ship on the stocks, and the other vessels at anchor near the fort[3]

St. John’s

The greatest part of the Buildings are not water-Tight, the Roofs only being covered with single Boards, which (the Engineer for the greater Dispatch, being obliged to lay on when quite green) are now split in many places. Those buildings therefore must be covered either with another Coat of Boarding or with shingles. The upright walls of the Log Houses have their seams partly chinked or caulked with Moss but not in a sufficient manner; it will therefore be necessary to compleat that caulking and afterwards to cover every seam within side & without with a coat of mortar or plaster. In some of the buildings the walls are covered with green boards which being no[w] shrunk almost as much as they can, it will be proper to cover them with a coat of laths and plaster.

A square [quadrilateral] fort is commenced between and extending backward from the two redoubts. Query, Does His Excellency the Commander in Chief intend to have that work pushed forward this season?

Isle aux Noix

The Wooden Buildings being much in the same Condition with those at St. John’s, The same improvements will be wanted.

N. B. I am humbly of opinion That in Order to prevent Fire among those Wooden Buildings the Roofs and Walls should be covered with a thick Coat of Lath & plaster especially those at St. John’s, where they are very close together. In regard to powder Magazines of Timber this seems to be indispensably necessary. Although this will occasion a little more Expences at first, yet it may be in the Main of the greatest frugality.[5]

From Captain Marr’s report it is evident that the transformation of Fort St. John’s into a larger and more defensible quadrilateral fort was still ongoing in the summer of 1777.

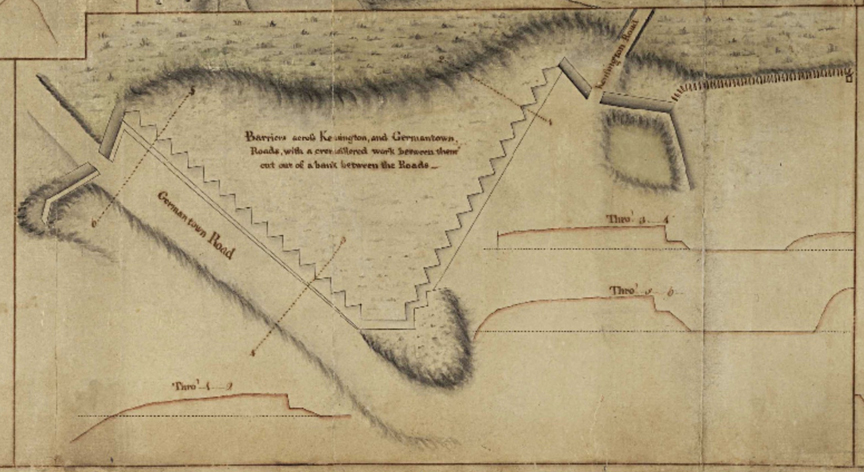

The Detached Redoubt

By 1778 a new detached redoubt had been commenced, which when finished would add another layer of defense to the already expanded and increasingly formidable works. It was strategically positioned on higher ground three hundred feet northwest of the quadrilateral fortification.[6] This was the area where Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery had, in 1775, set up a battery of four cannons and six mortars and successfully used them during the siege of Fort St. John’s.[7] The British would place nine strong cannon in their new detached redoubt so that they would be ready if the Americans ever attempted to approach them again from that direction. A straight-line ditch was dug between the main fortification and the detached redoubt to provide a safe line of communication for soldiers.

On July 19, 1778, the commanding engineer at Fort St. John’s, Lt. William Twiss, reported to the deputy adjutant general for Quebec, Capt. Francis Le Maistre, that the construction of the detached redoubt had been started and that work on the quadrilateral fort’s pickets was going forward:

The detached work I have marked out, and begun here, differs very much in its shape and Position from the proposed sketch I showed his Excellency, but being confident it occupies the most advantageous Ground I have no doubt of General Haldimands approbation: it is absolutely necessary that the Pickets which surrounded the present Fort here, should be taken down and replaced, I have given Lieut. Hockings Engineer my Idea of them, and the manner of securing the undefended Fronts of the old Redoubts[8]

Less than four months later, on October 1, engineer Lt. Richard Hockings reported to the new commander in chief for Quebec, Gen. Frederick Haldimand, that the detached redoubt was progressing well:

The Embrasures, Parapet, and Merlons of the detached Work on the West front of the picketed Fort [quadrilateral fort] are finished, and the Ditch round the same almost dug to its proper Depth and breadth. One of the Barracks is covered in and shingled, and the floor is now laying: The other Barrack is likewise in such forwardness, that I greatly flatter myself that we shall be able to get it covered in about a Week, provided the weather keeps fair. The Terreplein of the Work is also completing as fast as a sufficient Quantity of Earth can be brought in to form the Banquets and platforms.[9]

Reporting to General Haldimand one year later on February 1, 1779, Lieutenant Hockings stated that the picketing around the entire fortification was finished and the detached redoubt had been fully completed. More trees were being felled all around the fort to provide a clear line of sight towards any approaching enemies:

The new Picketing round the Garrison was begun the 18th November, and by the 15th December last [1778], the whole was completed with its Rampart. The small magazine and the Guardhouse in the detach’d Work, together with the line of Picketing to enclose the Gorge of that Work, were finished the begining of December. The North and South Redoubts, which joins the Picketed Fort, have been Repaired: All the Embrasures have been new done with log Work, Platforms new Laid; and the Parapets & Merlons raised: The Fraises round the two Redoubts have also been repaired, and the Ditches deepened. The Wood on the South front of the Garrison along the West side of the River, for the distance of about 1200 yards from the South Redoubt, has been fell’d, and cleared back from the Shore at least 150 yards . . . A great number of Trees have been Felled in front of the new detach’d Work on the West side of the Garrison as well as around the small work which incloses the Block House on the East side of the River; and several Wood Cutters are still employed on that Service to render the approach to these Works as difficult as Possible.[10]

Contained within the newly completed detached redoubt were four separate buildings: a guardhouse, a small magazine, and two separate barrack buildings. By December 21, 1779, William Twiss, recently promoted to captain and appointed chief engineer for Quebec, reported to General Haldimand that although Fort St. John’s as a whole was much advanced, some parts of the earthworks around the quadrilateral fort were still not finished. Hence, it would take many men one more full summer to get his unmitigated approval:

The Works at this post are much advanced and in a tolerable state of defence, but it will employ one Regiment during a whole Summer, to finish the Parapets, and Ditches already begun [around the quadrilateral fort]: To keep the Works clear of snow will probably prove a very heavy fatigue[11]

Nonetheless, by the spring of 1780 Fort St. John’s was the strongest British fortification in the Richelieu River-Lake Champlain corridor, containing thirty-six pieces of ordnance, more than double the total for Ile aux Noix and Pointe au Fer combined. Moreover, since it was also the key naval shipyard and dockyard for Lake Champlain there were many types of armed vessels coming and going.[12]

Fire in the Detached Redoubt at Fort St. John in 1780

On May 17, 1780, a destructive fire occurred in the detached redoubt at Fort St. John’s. Had that fire spread beyond the detached redoubt and engulfed the entire fortification including the naval dockyard, subsequent operations in 1780 may have been impossible. The next day the commandant at Fort St. John’s, Maj. Christopher Carleton reported to General Haldimand the shocking circumstances concerning this fire:

I have the mortification to acquaint your Excellency that yesterday Evening about a quarter before 5 o Clock, the whole of the Barracks in the Detach’d Redout appeared in flames without any previous alarm being given by the Detachment of Germans quartered there. The Magazine caught immediately & blew up in about twenty minutes, the roof having burnt through before the Explosion took place, prevented that part of the Parapet from being thrown into the Ditch; the Embrasures, Platforms, & Gun Carriages, are entirely consumed and a great Part of the Fascine work. The Iron Work will I hope, be all saved. I have the honour to enclose your Excellency Returns of the different Losses. I am informed the Fire first took in a new Barrack where the Carpenters were at Work by some shavings catching. its progress was incomprehensibly rapid, I am inform’d by some Gentlemen who were near the Redout that the whole appeared in a blaze almost instantaneously. Some of the timbers thrown out of the magazine fell in the Garrison, and one broke through the Roof of a House & set it on fire but by proper attention it was extinguished.[13]

Haldimand replied to Major Carleton from Quebec on May 20:

I have received your Letter reporting the unfortunate accident which has happened at St. John’s – a Circumstance, in the present moment exceedingly distressing to the Service. This letter will be deliver’d to you by Captain Twiss, whom I send to give the necessary directions for repairing the misfortune, & I rely upon your affording him every assistance possible. The two Companies [from Prince Frederick’s Regiment] that are to reinforce your Garrison will I hope enable you soon to accomplish this Service. Capt. Twiss will Concert with & be useful to you in making every Inquiry that may lead to a Discovery whether this Stroke has happened by accident or design. I willingly suppose the former but if thro’ negligence, the Parties concerned are surely very Culpable.[14]

Major Carleton wrote to Haldimand from Fort St. John’s on May 24:

I should have had the Honour of writing to your Excellency by this opportunity on the subject of the Late Fire but Captain Twiss’s arrival has induced me to Examine farther into the matter as I was, and am still disposed to think there was the appearance of design in the affair. I was at the Island [Ile aux Noix] when the matter happened having been called there the day before by the Assistant Engineer but came down between 5 & 6 the Morning after the Fire, therefore am obliged to judge from the circumstances as related by those were on the spot.[15]

Captain Twiss reported to Haldimand on May 24:

It was late last night before I reached St. John, this morning has been employed in examining the present state of the Works, and it is really incredible how entirely everything has been destroyed in the detached Redoubt, which can only be accounted for by considering that the dryness of the Season made everything burn with uncommon Fury, and that the Magazine was full [ablaze] half an hour after it took Fire before it blew up during which time no person could go near the Fort: The Heat was so intense that Several of the Iron Potts were melted. Major Carleton has made every possible inquiry into the cause of this accident, without making any other discovery than that the Germans say it was the Artificers and the Artificers say it was the Germans. Should a regular Court of Inquiry be assembled on the occasion I am convinced both would swear to their present openions, so that no truth could be discovered and I apprehend it might excite much ill will between the Two Nations which would have broke out before now, (had not Major Carleton’s good conduct prevented it) on account of the selfish behaviour of the Germans during the Fire; and indeed allowing them to be blameless with respect to the commencement of the Fire, yet their behaviour afterwards was certainly culpable, as they gave no alarm, and employed then whole Endeavours to take their own effects, which then want of Judgement induced them to carry to a great distance, and all this without making a single effort to stop the Fire, or preserve the Magazine.[16]

Captain Twiss further wrote in this report that there had been an earlier fire at Fort St. John’s in 1777 and that the previous commander-in-chief, General Carleton, had paid the officers and men for their losses suffered in that fire because “they had sacrificed their own effects to preserve the Public Stores which they effectually accomplished.”[17] Twiss continued, “In my humble opinion the Germans have not the same plea, to your Excellency’s Bounty.”[18]

General Haldimand replied to Twiss on May 29:

I have received your Letter of the 24th Instant, and from your Report of the Damage sustained at St. John’s & of Course, the Labour that will attend repairing it, I believe I shall order Prince Frederich’s Regiment to encamp near the Fort for the Purpose of assisting the Garrison in the Works[19]

Captain Twiss wrote to Haldimand from Montreal on May 31:

After a close examination of St. John, and the Isle aux Noix, with the services now at hand for those Posts I am to report to your Excellency that the Saw Mill at La Cote will amply supply Boards, for every Service which can be required in that quarter . . . At St. John we have begun the repair of the detached Redoubt, but as the interior space is small, I propose to have only ordered one half of the old Barracks to be rebuilt, proposing with your Excellency’s approbation, to build Barracks, equal to the other half within the Fort [quadrilateral fort]. I would have willingly avoided this expense but found the old boarded Barracks built in 1776, in such a state, that they cannot all be inhabited next winter without a great risk of the mens health who live there. I have placed a temporary Magazine in this Redoubt nearly similar to the former one, and have ordered the Doors, and Roof, which were the only parts exposed to view to be covered with sheet Iron[20]

Captain Twiss also described other work that was being undertaken at Fort St. John’s in the quadrilateral fortification. His final comment to Haldimand in this letter was that in view of all this construction work going forward, there was “no doubt but your Excellency will find the Fort [the entire Works – the quadrilateral fort and the detached redoubt] in its proposed state, very equal to any attack which the Enemy can bring against it.”[21]

The Aftermath: Fire Losses

A very interesting and highly detailed document titled “Return of Ordnance Stores lost by Fire in the detach’d Redoubt at Fort St. John’s 17th May 1780” precisely lists the numerous destroyed items:[22]

| Size or Type | Number | |

| Corned Powder Copper Hoopd W.B. [Whole Barrels] | 5 | |

| Paper Cartridges with Powder | 18 prs | 162 |

| 12 prs | 100 | |

| 4 prs | 100 | |

| Case Shot fixt to Wood Bottoms only | 18 prs | 100 |

| 12 prs | 38 | |

| 4 prs | 40 | |

| Case Shot fixt to Flannel Cartridges with Powder | 12 prs | 6 |

| Empty Paper Cartridges | 18 prs | 102 |

| Ladles with Staves | 18 prs | 4 |

| 12 prs | 2 | |

| 4 prs | 2 | |

| Spunges with Staves | 18 prs | 3 |

| 12 prs | 2 | |

| 4 prs | 2 | |

| Wadhooks | 18 prs | 4 |

| 12 prs | 2 | |

| 4 prs | 2 | |

| Garrison Carriages with Wood Trucks | 18 prs | 5 |

| 12 prs | 2 | |

| 4 prs | 2 | |

| Beds & Coins | 18 prs | 5.10 |

| 12 prs | 2.4 | |

| 4 prs | 2.4 | |

| Iron Aprons with Chains | 9 | |

| Claw Hammers | 2 | |

| Steel Spikes for nailing Guns | 8 | |

| Punches for Vents | 1 | |

| Portfires – Dozens | 1 | |

| Portfire – Sticks | 2 | |

| Tin Tube Boxes | 12prs | 2 |

| Lanthorns | Muscovy | 1 |

| Tin | 1 | |

| Dark | 1 | |

| Linstocks | with Cocks | 2 |

| without Cocks | 3 | |

| Powder Horns | 4 | |

| Priming Wires | 4 | |

| Match C. 2. lbs | C. 2. lbs | 0.2.0 |

| Tann’d Hide | 1 | |

| Hair Cloth | 1 | |

| Handspikes | 18 | |

| N. B. The following Iron Ordnance was mounted on Garrison Carriages in the Redoubt [they are not specifically mentioned as being destroyed in the fire but the Gun Carriages with Wood Trucks listed above were destroyed] | 18 prs | 5 |

| 12 prs | 2 | |

| 4prs | 2 |

It is apparent from the list that five whole barrels of black powder, and three hundred and sixty-two paper cannon cartridges with powder, exploded with devastating ferocity. Thus, the ordnance supplies for the nine cannons, as well as the buildings, in the detached redoubt were annihilated. The only other extant list of items lost in the fire was recorded in a separate document originally written in French but translated here into English, titled: “Baggage Report [of] what the Company of Lieutenant Colonel Praetorius in the Prince Frederic Regiment lost in the fire at St. Jean on May 17, 1780.”[23]

| [Name of Object] | [Number] |

| Halberds | 7 |

| Fusils | 16 |

| Bayonets | 31 |

| Cartridge boxes | 18 |

| Cartridges | 5000 |

| Gun flints | 400 |

| Belts with buckles | 29 |

| A box | 1 |

| Haversacks | 45 |

| Sabres | 22 |

| Habits [Long loose garments] | 13 |

| Jackets | 14 |

| Hats | 19 |

| Collars with buckles | 39 |

| Ribbons of tails | 50 |

| Pots | 4 |

| Cooking pot bags | 4 |

| Bread bags | 141 |

| Canteens | 16 |

| Summer breeches | 73 |

| Shirts | 165 |

| Shoes | 96 |

| Stockings | 50 |

| Shoe soles | 163 |

| Cutlery | 70 |

| Waxed canvas tent cover | 1 |

| A strap of a box | 1 |

| The Loss of the Officers Baggage | |

| 1. Of the Lieutenant Knesebeck is at least | 24 Sterling |

| 2. Of the Ensign Hille is at least | 18 Sterling |

| Medicine and Surgical Instruments is at least | 12 Sterling |

Lt. Col. Christian Julius Praetorius’s company lost a multitude of items ranging from halberds, fusils, bayonets, cartridges, gun flints, and sabres, to a large variety of clothing items. They even lost their bread bags and cutlery. The five thousand musket cartridges packed with black powder would have been highly flammable and contributed to the intensity of the flames. Were the officers ever remunerated for their losses? If Captain Twiss had anything to do with the final decision, they received nothing because he felt that they had not done enough to put out the devastating fire. This may have been too severe a critique because the entire detached redoubt was very quickly blown to pieces. What would have happened to the Germans if they had stayed and tried to stop the fire? As Major Carleton wrote, “The Magazine caught immediately & blew up in about twenty minutes, the roof having burnt through before the Explosion took place . . . its progress was incomprehensibly rapid, I am inform’d by some Gentlemen who were near the Redout that the whole appeared in a blaze almost instantaneously.”[24] Did Lieutenant Colonel Praetorius’ company display cowardice or cognition? Most likely the latter.

The fire at Fort St. John’s in 1780 was remarkable for many reasons. No one died, or is known to have been seriously injured. Furthermore, it was providential that out of the fortification’s approximate total of forty-five buildings, only four were destroyed.[25] And when one considers the primary importance of Fort St. John’s to the British for both strategic and tactical purposes its loss would have had far reaching effects if more of the fort or the shipping on the Richelieu had been significantly damaged or destroyed. As it stood, the Crown Forces were able to send four “large-scale raids into the Hudson, Schoharie, and Mohawk valleys” in October 1780.[26] Three of these raids assembled at Fort St. John’s before setting out on their expeditions. From the British viewpoint they were highly successful because they laid waste to Gen. George Washington’ s grain stores and thereby reduced the probability that the Americans would invade Canada again in the near future.

[1] The British also referred to Fort St. John’s as Fort St. John or St. John’s. Presently, one can see the remains of some of Fort St. John’s ramparts and visit the fascinating Musee du Fort Saint-Jean which details centuries of history. Both are located at the site of the Royal Military College Saint-Jean, 15 Jacques-Cartier North Street, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, QC, J3B 8R8.

[2] Russell P. Bellico, Sails and Steam in the Mountains: A Maritime and Military History of Lake George and Lake Champlain (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2001), 3.

[3] Thomas Anburey, Travels through the Interior Parts of America, Vol. I (London, UK: William Lane, 1789), 132, 136. Thomas Anburey was a volunteer in the 29th Regiment of Foot in 1776; by 1777 he was serving in the 24th Regiment of Foot.

[4] Andre Charbonneau, The Fortifications of Ile Aux Noix (Ottawa, ON: National Historic Sites, Parks Canada, 1994), 71.

[5] John Marr to Guy Carleton, June 17, 1777, Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-154, images 3-4, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/3.

[6] The distance separating the detached redoubt from the quadrilateral fort can be ascertained by using the correct “Scale 200 feet to an Inch” and not the “Scale 20 feet to an Inch,” both of which are found on the “Plan of Fort St. John on the River Chambly” by Gother Mann dated May 7, 1791, central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=4129856&lang=eng&ecopy=n0016455k.

[7] The battery of four guns and six mortars are clearly marked on the “Plan of St. John’s as blockaded and besiegd anno 1775” found in: Arthur G. Doughty, Report Of The Work Of The Public Archives For The Years 1914 And 1915: Appendix B: Papers Relating to the Surrender of Fort St. Johns and Fort Chambly (Ottawa, ON: J. De L Tache, 1916), 3.

[8] William Twiss to Francis Le Maistre, July 19, 1778, Great Britain, War Office: America (WO 28): C-10681, Volume 6, image 15, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c10861/15.

[9] Richard Hockings to Frederick Haldimand, October 1, 1778, Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-154, image 88, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/88.

[10] Hockings to Haldimand, February 1, 1779, Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-154, Images 140-141, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651.

[11] Twiss to Haldimand, December 21, 1779, Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-154, image 232, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/232.

[12] “State & Distribution of the Brass & Iron Ordnance in Canada according to the latest Returns, April 8, 1780,” Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-156, image 981, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/981.

[13] Christopher Carleton to Haldimand, May 18, 1780, Haldimand Papers: H-1453, B-133, image 531, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1453. Maj. Christopher Carleton was in the 29th Regiment of Foot and was the nephew of Gen. Guy Carleton.

[14] Haldimand to Christopher Carleton, May 20, 1780, Haldimand Papers: H-1453, B-135, image 1170, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1453/1170.

[15] Christopher Carleton to Haldimand, May 24, 1780, Haldimand Papers: H-1453, B-133, image 536, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1453/536.

[16] Twiss to Haldimand, May 24, 1780, Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-154, images 260-261, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/260.

[17] Ibid., 261.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Haldimand to Twiss, May 29, 1780, Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-154, image 267, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/267.

[20] Twiss to Haldimand, May 31, 1780, Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-154, images 268-269, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/268.

[21] Twiss to Haldimand, May 31, 1780, Haldimand Papers: H-1651, B-154, image 270, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/270.

[22] “Return of Ordnance Stores lost by Fire in the detach’d Redoubt at Fort St. John, 17th May 1780,” Haldimand Papers, H-1651, B-156, images 983-984, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/983.

[23] “Baggage Report [of] what the Company of Lieutenant Colonel Praetorius in the Prince Frederic Regiment lost in the fire at St. Jean on May 17, 1780,” Haldimand Papers, H-1651, B-156, image 985, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1651/985.

[24] Christopher Carleton to Haldimand, May 18, 1780, Haldimand Papers: H-1453, B-133, image 531, heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1453.

[25] The total of forty-five buildings in the quadrilateral fort and the detached redoubt at Fort St. John’s in 1780 is an estimate because there is no extant 1780 plan view to study. This approximation is based on two separate plan views of Fort St. John’s. “A South-West View of St. Johns, Quebec, with Plan,” dated August 1779 shows approximately forty buildings in total, but only two in the detached redoubt when it is known there were four there in 1780. “Plan of Fort St. John on the River Chambly [Richelieu],” dated May 7, 1791, shows forty- five buildings in total, and the correct four buildings in the detached redoubt. It is possible that this plan showed the fortification as it was in 1783 and maybe as early as 1780 when the detached redoubt blew up.

[26] Gavin K. Watt, The Burning of the Valleys: Daring Raids from Canada against the New York Frontier in the Fall of 1780 (Toronto, ON: Dundurn, 1997), 59.

2 Comments

These are very valuable accounts of the history of an important location in the Revolutionary War, and deserve to come to the attention of all people studying the conflict. Equally important are the graphic illustrations accompanying the text, which (for example) show some of the few eye-witness art-works of particular ships that fought on Lake Champlain

Yes, the history of Fort St. John’s is a fascinating and somewhat understudied topic. Thank you very much John for your kind words of validation and encouragement.