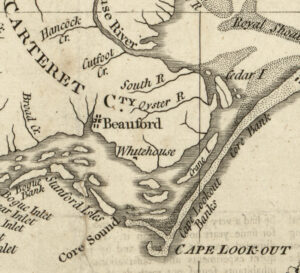

The mention of Beaufort, North Carolina, does not typically bring to mind any significant activity of the American Revolution. Only the most serious students of the war are likely to have studied the role Beaufort played. The action there offered no turning point and no clash between well-known commanders or sizable forces, but in the spring of 1782 Beaufort was the victim of a violent attack and occupation by Loyalist forces. It is common for military events after the British surrender at Yorktown to have historiographical shortcomings, but particularly Beaufort. Its story, often confused with a clash in Beaufort, South Carolina around the same time, is consistently inaccurate in secondary sources. The motivation behind the attack, and the narrative of what took place after the Loyalists came ashore, require a historiographical update. We are fortunate that several obscure pieces of scholarship augment the primary sources and make such a task possible.

An aged and out of print work by a local historian and an equally aged and overlooked academic journal article provide key evidence that, when weaved together with primary sources, yields a fresh look at the occupation of Beaufort. The first source, a detailed history of Carteret County, North Carolina, during the Revolution by local historian Jean Bruyere Kell, is the only legitimate narrative of the two-week affair.[1] The second, a seemingly unknown journal article by North Carolina historian Jeffrey J. Crow, fills in the political and operational details the historiography consistently lacks.[2] It provides clear evidence that the attack was not, as many have claimed, planned and carried out by Loyalist Maj. Andrew Deveaux, and that it was not ordered by Maj. Gen. Alexander Leslie, but rather a man named John Cruden, a North Carolina Loyalist who held the position of commissioner of sequestered estates under Gen. Charles Cornwallis.[3] Cruden’s involvement in the attack has been completely missed by most writers and its inclusion reveals a fascinating and complicated story indicative of the bloody and lawless war waged by Loyalists and Patriots in the months following Yorktown.

Rebel spies within Charlestown sent word to Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene at the end of March that Loyalist forces planned to attack Beaufort. Greene warned Gen. Jethro Sumner, writing that, “I send you a piece of intelligence just come to hand which I believe may be depended upon, and I fear the execution will take place before this can reach you.” He advised Sumner that a small fleet of ships were headed directly for Beaufort to plunder and destroy the town, “where they are informed are a large quantity of public and private stores.”[4] This was an incredibly accurate piece of intelligence by any war’s standards, but particularly so for the Revolutionary War. Greene’s letter directed Sumner to “take every possible step in your power to defeat the enemy’s designs,” but there is no evidence that Sumner took action to follow Greene’s order.[5]

It is unknown why Sumner seemingly offered no response of any kind or what he did with the intelligence; he may have sent it on to North Carolina Gov. Thomas Burke. Burke’s correspondence provides some clues but no conclusion. The first mention by Burke of the event is buried near the end of an April 12 letter to Greene, where he briefly relayed that “I have just received some reports of the landing of some British troops at Beaufort in this state but not authenticated. I can see no object for them and can scarce credit it.”[6] The language indicates he had no prior information on any move upon Beaufort, and his complacency on the matter is apparent. The records available do not say when he first learned of the invasion or from whom. Indications are that he learned on or around April 12, a full nine days after the first view of the fleet and nearly two weeks since Greene had warned Sumner.

No reason for the woefully slow communication is clear, but it continued. Several days passed before Governor Burke took action. He wrote to both Gen. Richard Caswell and Gen. Isaac Gregory on April 16, ordering each to raise five hundred men to oppose the enemy.[7] The next day he informed the state’s general assembly of the affair, writing to them, “I send you some intelligence which came to hand late last night.”[8] The intelligence message he sent matches exactly Greene’s warning to Sumner, so it is possible that it was forwarded from Sumner, as no letter from Greene to Burke on the topic is known to exist, and Burke’s mention of the attack to Greene does not strike the tone of a reply to a previous conversation. Burke’s knowledge and timeline remain a mystery, but his and Sumner’s lack of urgency and action are clear. Burke’s call for troops and messages to the general assembly were too late, and by April 20 he was aware of that and circulating followup letters to military leaders calling off his previous orders. While generals and politicians took their time, a fascinating confrontation between Patriots and Loyalists took place.

The small Loyalist fleet appeared within sight of Beaufort on the third of April. Several members of a whaling crew resting on a nearby shore area of Shackleford Banks were the first known to have seen them. The three ships dropped anchor offshore from the whalers and took a small boat ashore. The Loyalists identified themselves as privateers, telling the whaling crew two of their ships were captured prizes and they were looking for a safe port of refuge. They asked for help navigating into the port of Beaufort and the unsuspecting whalers and townspeople provided it. At the following day’s high tide, pilots were seen boarding the ships, and they guided the floating Trojan horses over the sand bar and directly into the port of Beaufort.[9]

From there, the Loyalists continued their ruse and executed a series of tactical tricks. Several times citizens rowed out to the anchored ships to greet the visitors and appease their own curiosities; each time hours passed, and no one returned from the ships. The second group of curious visitors included county militia Capt. Dedrick Gibble; when he did not return suspicions that the visitors had a nefarious purpose finally arose.[10] A militia officer on shore, Maj. William Dennis, rode to the nearby plantation of Col. John Easton and passed on his suspicions. Those previously informed of threats upon Beaufort did next to nothing, but Easton broke the cycle and called out the Carteret County militia. By nightfall militia descended upon Beaufort and began nighttime patrols. A patrol with Colonel Easton came across a group of men trying to come ashore by convincing a militia sentry they were friendly, but the time for ruses was up and a small exchange of gunfire sent them scurrying off in the darkness and away on their boat. It was only the beginning for Beaufort.

Colonel Easton and his men continued patrols throughout the night, and on the morning of April 5 the situation broke loose when the Loyalists began their push ashore. Sentries spotted and fired upon a group of them just as the sun rose, and this time it was more than a simple exchange of gunfire: men were wounded. One Loyalist private received wounds serious enough to be fatal the next day, after he lived long enough to request being buried “standing in salute to his King.”[11] In a short time Loyalist troops were pushing ashore in various places and Colonel Easton’s militia were outnumbered. As the day progressed the militia retreated through town, mixed in with Loyalists roaming freely from house to house, the two sides crossing paths, exchanging fire, and taking prisoners at various points.

The chaotic scene unfolded all day. Additional members of the county militia trickled in, but not enough to stop the enemy’s advance. Col. Enoch Ward of the Carteret County militia arrived around 2 p.m. with twenty additional men. Patriot militia gathered at the bridge crossing the creek on the edge of town and contained the Loyalists to Beaufort proper, inhibiting any spread into the countryside, while supplying a safe haven for militia troops and townspeople to gather in safety. Beaufort’s citizens took advantage and trickled into the new rally point throughout the afternoon and evening. They brought with them the few belongings they could save, and stories of those they could not.

Women with children and old folks began to arrive with tales of ruthless plunder. They told of the British entering their homes, taking furniture and any object they could carry, sashing those pieces too large to move, slitting open feather beds and strewing the feathers through the house and in the streets, grabbing women and tearing their clothes from them and searching their petticoat pockets. All came in great distress to the protection of the camp.[12]

At nightfall the stage was set. The British held the town and shaken, angry townspeople occupied the other side of the creek, watching them as they took what they pleased and destroyed their property.

Each side took prisoners during the clashes of April 5. As a prisoner aboard the British ship Peacock on April 6, Carteret County militia Capt. William Bull sent a message ashore stating that the British fleet commander, Capt. Duncan McLean, asked that no force be used against his men, as they had no intention of destroying the town and sought a prisoner exchange. The message was ironic to say the least! The town had already been heavily damaged. Easton’s personal reaction is not recorded, but it is no stretch to imagine his possible frustration or anger. Whatever his emotion, he agreed to meet and discuss an exchange.[13]

When the two sides met on April 7 no agreement for prisoner swaps was reached. Small exchanges of fire took place over the next two days and twice the British fired a cannon ball into the camp occupied by civilians. Tensions remained high. On the 8th an exchange of fire around the town schoolhouse saw the British retreat behind it for cover and later set fire to it, destroying the structure completely. That night a nearby plantation belonging to William Borden was attacked and raided. The British destroyed his warehouse and mill before carrying off several of his enslaved people.[14] The taking of slaves, regarded as personal property of the highest value, was an escalation of the already high tensions.

A meeting on the 9th yielded movement toward a prisoner exchange, and both sides agreed to swap their prisoners the following day. At daybreak on April 10, the people of Beaufort awoke to discover that overnight British forces had evacuated the town and returned to their ships, with their American prisoners. The Americans released their prisoners at the appointed time, but the British did not, and the saga continued. Patriot forces reoccupied the town and once more looked out at several British ships at anchor in the harbor just as they had five days prior. British forces had largely been contained to the town those five days. With the exception of their raid on the Borden plantation they had little success moving inland or upon any of the nearby coastal areas. Carteret County militia and late-arriving militia forces from surrounding counties had harassed them at every opportunity. Their withdrawal was motivated by their search for replenishment of their low fresh water stock; the militia had prevented them from obtaining enough to sustain their occupation.

Rather than immediately sailing away they lingered nearly an additional week. Intermittent exchanges of cannon fire between ships and shore kept the residents of Beaufort vigilant. Militia scouts patrolled the shorelines constantly and each Loyalist attempt to sneak ashore and gather fresh water was met with harassing fire. Several Loyalists were killed in an exchange on April 12, and while the remainder escaped back to their boats, their water casks were seized by Patriot forces, a loss that certainly made the Loyalists’ situation more untenable.[15] Finally on the night of April 15, Beaufort’s citizens launched a flotilla of burning rafts toward the small fleet hoping to set fire to it. Several rafts came close but all missed their target.[16]

The desired effect was achieved nonetheless. The next morning the fleet was observed making preparations to sail, but unfavorable winds kept them in the harbor an additional day, during which they launched no shore excursions. Finally, the next morning, Wednesday April 17, the citizens of Beaufort awoke and witnessed the fleet catching a favorable wind and sailing out of the harbor. Once clear, they paused briefly and released the pilots and prisoners they had held throughout the siege, but they did not release the enslaved people taken from the Borden plantation.[17] After nearly two weeks the siege was over. The danger had passed, but the town of Beaufort was left heavily damaged and its citizens psychologically scarred, a full six months after the American victory at Yorktown when many thought the war was finally behind them.

Through a careful review of the historiography and primary sources a new and complete picture of the event emerges. Historian Jean Bruyere Kell’s work, in a publication of the Carteret County Bicentennial Commission, is well sourced, and while the text lacks a smooth flow and is devoid of any prose, it does provide a narrative of the daily confrontations between Patriots and Loyalists drawn from primary sources. The scholarship, including the most recent to mention the attack on Beaufort, consistently credits Loyalist Major Andrew Deveaux with planning and leading the operation. Jeffrey J. Crow’s article provides a clarifying look at the operational details behind the attack and clearly dispels the claim that Deveaux planned or led it, stating clearly that, “The impetus for this small-scale invasion emanated from South Carolina where the British were preparing to evacuate Charlestown. It was not British military strategists who masterminded the attack, but John Cruden, a North Carolina Loyalist and commissioner of sequestered estates for Lord Cornwallis.”[18]

Cruden’s job was to oversee property the British had sequestered, supply the British army with critical provisions, and even to see confiscated estates turn a profit for the Crown. This was a stressful job to say the least, and one that put Cruden squarely in a position to make enemies on all sides. Property often changed hands back and forth depending on which side controlled territory, raids were common by all sides, and enslaved people often ran away to the British seeking freedom, making many of the plantation estates less likely to turn a profit. These challenges, as Crow points out, “boded ill for Cruden’s personal finances.”[19] Cruden often put his personal money into struggling estates, betting on his investment to pan out long term, as he was entitled to a portion of any profits, but the British surrender at Yorktown changed everything, and desperate parties took desperate measures when they sensed the war was coming to a close.

The influx of refugees in Charlestown had only worsened the shortage of supplies there. In early 1782 the British were feeding not only their own army but also Loyalists on the run from revenge-seeking Patriots and runaway slaves seeking freedom behind British lines. Cruden had lobbied previously that untapped areas of the North Carolina coast could supply the British army, an argument even more prevalent in early 1782. As Crow wrote, “It was at this desperate juncture that Cruden cast a hungry eye toward the bulging storehouses of maritime North Carolina.”[20] He had used cooperation with the military and privateers paid with his own money in the past and he turned to that strategy once more, authorizing, planning, and launching the attack on Beaufort, North Carolina.

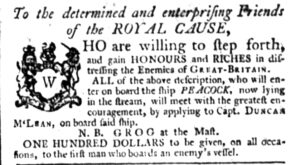

In perhaps a bit of historiographical irony, the operational details misunderstood in modern coverage of the invasion were openly available in 1782. In Charlestown, neither the invasion nor Cruden’s involvement was a secret, as evidenced by the notably accurate letter to General Sumner warning of the invasion. The details were in fact printed in Charlestown’s Royal Gazette. The equivalent of a modern-day help wanted ad appeared in the March 6, 1782 edition, seeking volunteers “willing to step forth, and gain honors and riches in distressing the enemies of Great Britain” to apply aboard a privateer ship named Peacock under the command of Capt. Duncan McLean.[21]

Colonel Easton’s report to Governor Burke immediately after the attack indicated that Cruden was responsible. He wrote to the governor that the attack was carried out with “private property fitted out by one Cruden from Charlestown, Refugees [loyalists] supported by about 70 Regulars, for the purpose of plundering, destroying, all public Stores, and laying waist Mills, and Salt Works of every kind.”[22] How Easton knew of Cruden’s involvement is not known, but it is clear that this information traveled from Charlestown to Beaufort along with the fleet.

The theft and destruction of private property perpetrated by the British invaders was never part of Cruden’s plan. Their treatment of the town’s citizens and wanton destruction of its infrastructure infuriated him. He was, in fact, so disturbed by the damage to Beaufort that on May 25, 1782, he took a large advertisement in the Royal Gazette apologizing to the citizens and personally calling out the “excessive enormities and depredations.”[23] The advertisement included clear evidence that the fleet was sent by Cruden personally. He labeled the violence a “direct and flagrant violation of my orders” by the expedition’s leaders, Captains Duncan McClean and Patrick Stewart, “which I meant to be strictly and unequivocally obeyed, as I declared the plan was primarily undertaken and intended by me to be prosecuted upon the most liberal principle of hostile retaliation.”[24] Cruden went so far as to promise the inhabitants of Beaufort restitution for the damages, a hollow promise he was not able to fulfill.

The few historians that make brief mention of Beaufort have completely missed Cruden’s involvement. One recent work continued the trend, writing of the raid that, “Frustrated by contested foraging operations around Charleston, General Leslie sent a large Loyalists force to capture Continental warehouse food and other supplies in Beaufort, North Carolina.”[25] In addition, some authors may have confused the Beaufort, North Carolina operation with Major Deveaux’s attack on Beaufort, South Carolina only a few weeks before. The newspaper coverage in the Royal Gazette, which matches the record remarkably well, does not mention either Leslie or Deveaux.[26] It is clear from the evidence that General Leslie had nothing to do with the operation and Major Deveaux did not take part in any way.

With an accurate narrative of the attack now clear, it is arguable that Beaufort should be viewed as a missed opportunity for the Patriots. As with many events during 1782, the cooperation between the military and political establishments was woeful, and costly. Had General Sumner and Governor Burke heeded the warnings given to them sooner, perhaps the situation could have been avoided, or at least mitigated. Perhaps the Patriots could have used the intelligence as a means to wage a surprise offensive operation or set a trap, rather than conducting yet another disastrous defensive engagement. Beaufort demonstrates an opportunity the army should have been ready for, but the governor and others were complacent, allowing the Loyalists to land a heavy blow on a Patriot stronghold.

The historiographical focus after Yorktown shifts dramatically to the political events of the era at great expense to the military. There are numerous examples similar to Beaufort, stories well worth the time to update our understanding of the bloody war between Patriots and Loyalists after their parent armies had ceased their own exchanges of fire in large scale engagements. Many of these stories are as fascinating as they are overlooked, and ripe for future articles on their details.

[1] Jean Bruyere Kell, North Carolina’s Coastal Carteret County During the American Revolution, 1765-1785 (Greenville, N.C.: Era Press, 1975), 21-27.

[2] Jeffery J. Crow, “What Price Loyalism? The Case of John Crudden, Commissioner of Sequestered Estates” The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 58 No. 3 (July 1981), 215-233.

[3] Crow, “What Price Loyalism?,” 216. Among those to make those attributions are Patrick O’Kelley, Nothing But Blood and Slaughter: The Revolutionary War in the Carolinas, vol. 4, 1782 (Lillington, NC: Blue House Tavern Press, 2003), 50, and Kenneth Scarlett, Victory Day: Winning American Independence, The Defeat of the British Southern Strategy (Charleston: Palmetto Publishing, 2022), 220.

[4] Nathanael Greene to Jethro Sumner, March 30, 1782, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, vol. 10, 3 December 1781-6 April 1782, ed. Dennis M. Conrad, Roger N. Parks, and Martha J. King (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 563.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Thomas Burke to Greene, April 12, 1782, The Papers of Nathanael Greene, vol. 11, 7 April-30 September 1782, ed. Dennis M. Conrad and Roger N. Parks (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 46.

[7] Burke to Richard Caswell and Isaac Gregory, April 16, 1782, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, ed. Walter Clark, vol. 16, 1782-1783 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1900), 595-96.

[8] Burke to the North Carolina General Assembly, April 17, 1782, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 16:286.

[9] The foremost primary source for the attack and occupation is a five-page letter from Carteret County militia Lt. Col. John Easton to Governor Burke dated April 19, 1782. It served as an after action report to the governor and gives names, dates, and times. Easton titled the letter, “Movements Relative to the Enemy that Landed at Beaufort on the Morning of 5th April 1782.” See John Easton to Burke, April 19, 1782, Governors’ Papers: Thomas Burke, Correspondence, April 1782, North Carolina Digital Collections, State Archives of North Carolina, digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/governors-papers-thomas-burke-correspondence-april-1782/999234?item=999364.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Kell, North Carolina’s Coastal Carteret County, 22.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Easton to Duncan McLean, April 6, 1782, in Kell, North Carolina’s Coastal Carteret County, 43.

[14] Easton to Burke, April 19, 1782.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Crow, “What Price Loyalism?,” 216.

[19] Ibid, 221.

[20] Ibid, 224.

[21] Royal Gazette (Charlestown), March 6, 1782.

[22] Easton to Burke, April 19, 1782.

[23] Royal Gazette (Charlestown), May 25, 1782.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Kenneth Scarlett, Victory Day: Winning American Independence, The Defeat of the British Southern Strategy (Charleston: Palmetto Publishing, 2022), 220.

[26] Royal Gazette (Charlestown), April 17, 1782, and April 24, 1782.

4 Comments

The Old Burying Ground in Beaufort marks the grave of a “British Officer” in His Majesty’s Navy who died onboard during the town’s invasion. Not wanting to die “with his boots off,” he was buried standing up in full uniform: “Resting ‘neath a foreign ground / Here stands a sailor of Mad George’s crown / Name unknown, and all alone, / Standing the Rebel’s Ground” [Brantley].

Dr. Jeffrey J. Crow, historian cited in the article, is a widely published author of the state’s history. He is former director of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History and deputy secretary of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.

Scott….thank you, and indeed Dr Crow’s work was a great help for this article and has been a part of my overall research for the events of 1782.

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often get lost in wider histories.

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work of the post Yorktown era as well! Exploring these lost stories from the post Yorktown era has been challenging but also very rewarding.