Nathanael Greene famously wrote of his experience during the Southern Campaign that “The whole Country is in Danger of being laid Waste by the Whigs and Tories who pursue each other with as much relentless Fury as Beasts of Prey.” Historian John Pancake comments that “This observation was made by Nathanael Greene, a man already hardened by six years of war. In those six years Greene had never seen anything like the civil war that raged in the Carolinas. Nowhere in America was the fighting more bitter and savage.”[1] And yet, in the first fatal encounter of the American Revolution in the South, the Battle of Old Savage’s Fields, which took place from November 19 to November 22, 1775 near the backcountry town of Ninety Six, there appear to have been only two dead and at most only a few dozen wounded—a number more than fifty times smaller than the over one hundred killed in the April 19, 1775 battles of Lexington and Concord. How are we to account for such low casualties considering what the war in the South would become?[2] The comparatively low numbers of casualties were due to the pre-war history of the backcountry, the nature of South Carolina politics following the creation of its Provincial Congress, and the circumstances of the battle itself.[3]

Prelude to Battle

In 1775, South Carolinians angry with what they saw as the violation of their rights by the British government established their own government, the Provincial Congress, with the Committee of Safety serving in an executive capacity. On June 30, representatives of this government issued “A Circular Letter to the Committees in the Several Districts and Parishes of South Carolina” in response to news of the April battles of Lexington and Concord. While critical of the king, that letter focused on how “British Ministers . . . in pursuit of their plan to enslave America, in order that they might enslave Great Britain; to elevate the Monarch that has been placed on a Throne only to govern under the law—into a Throne above all law.” In order to respond to this plot and the violence that the British government was willing to undertake to achieve it, as witnessed by events in Massachusetts, the Provincial Congress would reorganize its militia, raise new military units, and create an “association” of people who accepted the authority of the new South Carolina government, with those who refused to join being treated as “enemies of the liberty of America.”[4] In this way, the Congress presented itself as the sole legitimate legal authority, acting in accordance with the law, placing those who remained loyal to the royal government, represented by Governor William Campbell, as outside the law.

Arguably the first act of war in the South occurred a couple of weeks later on July 12 when a group of soldiers under the command of Maj. James Mayson acting on the orders of the Council of Safety seized Fort Charlotte, a backcountry outpost.[5] Mayson then took some of the gunpowder seized there to Ninety Six. Moses Kirkland, a militia officer who had accompanied Mayson, along with other Loyalists, including brothers Robert and Patrick Cunningham, arrested Mayson and placed him in the jail there, though he was later released. This incident illustrates the divisions in the backcountry—not all were willing to become “Associators” and it was not clear on which side any individual stood. Moreover, neither side was willing to shed blood or even imprison their opponents.

While the Loyalists seemed to have wanted to maintain their position in the Backcountry, the Charlestown government wanted to expand its power there. For instance, on July 23 the Council of Safety ordered William Drayton and Presbyterian minister William Tennant to tour the area in an effort to win support for the Provinicial Congress.[6] As noted in Tennet’s journal of the time, their mission would meet with mixed success at best, provoking even greater concerns over the backcountry.[7] Strikingly, Tennant did not face significant harassment from Loyalists, even if there were at times verbal altercations.

While extant documents primarily focus on the Whig perspective, an important one that that gives us a sense of that of the Loyalists was sent on July 24, the day after Drayton and Tennent were officially given their mission, by Thomas Fletchall to the president of the Council of Safety. In that letter, Fletchall stated why he would not sign the “Association Paper,” explaining that “I must inform you, sir, I am resolved, and do utterly refuse to take up arms against my king, until I find it my duty to do otherwise and am fully convinced thereof.”[8] On one side, Fletchall was taking a real risk by refusing to accept the Association. On the other, this is hardly a ringing call to fight, but rather a strong expression of the desire to be left alone.

Other friends of the king felt that more decisive action was needed and organized their own militia forces, leading Drayton to issue a proclamation against such activities on September 13. The document backed away from overt criticism of the king, instead asserting that it was the ministers who were “deceiving” the monarch and that “tools of administration,” that is, the agents of those ministers in South Carolina, had hoped “at this calamitous time, to rise in the world by misleading their honest neighbors … to raise in this Province an opposition to the voice of America.”[9] This was a clear attempt to convince Backcountry Loyalists to accept the Association by playing down its more radical claims, as seen in the above circular letter. A willingness to accept such arguments can be see in the successful negotiation on September 14 by Drayton and Fletchall of a “Treaty of Ninety Six,” that presented the conflict between the parties as having broken out on account of “misunderstandings,” the clearing up of which would allow “all parts of the Colony to live in peace and friendship with each other.”[10]

Key to the treaty was the promise that if British regulars arrived to enforce Crown rule, the Loyalists would take no action to support them. The treaty also recognized the authority of the Provincial Congress and the arrests it might make of Loyalists who opposed it. Naturally, some Loyalists found such an agreement a dangerous surrender of their principles and even their personal safety. And when the aforementioned Robert Cunningham was asked by Drayton whether he considered himself bound by the treaty, he responded in an October 5 letter that it was too one-sided and had been forced on a frightened Fletchall, stating that “I do not hold with that peace.”[11] This led the Council of Safety to order the arrest of Cunningham, who was captured by Andrew Williamson, who would command Whig forces at Savages’ Old Fields, and thrown into jail in Charlestown.

The arrest of Cunningham naturally concerned many Loyalists. In contrast, his capture seems to have convinced Drayton that he could safely shift his focus away from Backcountry whites to relations with the Cherokee. Hoping to win their neutrality in any coming conflict, he arranged the dispatch of a large amount of gunpowder and lead as gifts to them. However, on October 31 Loyalists led by Patrick Cunningham, believing that the Native Americans were being supplied with weapons to attack them, ambushed and seized what they could carry away and destroy what they could not.[12] Strikingly, not only did they not harm any in the caravan transporting the supplies, they allowed them to go free. The stage for the Battle of Savages’ Old Fields was set, as the Provincial Congress would send out Whig forces to recapture the pilfered supplies and arrest Loyalist leaders, while the latter would further organize to protect themselves lest they suffer the fate of Robert Cunningham or worse.[13]

Though there had been ample opportunity for violence, no one had been killed or even seriously injured in the incidents described above. There were multiple factors inhibiting violence that can be found in the recent history of the backcountry and the political developments following the creation of the Provincial Congress. For one, the King’s men seemed to have largely wanted to be left alone rather than to wage an actual war against the Whigs. Conversely, the Whigs sought to isolate Loyalist leaders while winning the support of the white population of the Backcountry. Should the Loyalists turn to violence, that would invite a stronger push by the Provincial Congress into the backcountry, while violent acts by the Whigs would undercut their conciliatory approach. And since there was as yet no Declaration of Independence, it was not entirely clear where the lines of loyalty lay.

Another reason why backcountry whites would have been hesitant to use lethal force against each other is that the region’s recent history had encouraged unity. Since the 1750s, Backcountry whites and some African Americans had fought against the Cherokee and other Native Americans. And no sooner had those conflicts reached a temporary cessation than the rise in criminal gangs led to the Regulator movement, in which backcountry vigilantes sought to establish law and order, a need created by the refusal of Charlestown politicians to allow for the building of legal institutions in the Backcountry. Such conflict was largely resolved in the 1770s when courts and jails were established in the region, including in Ninety Six, thanks to the persistent and unified campaign waged by the Backcountry against the planter-dominated colonial government.[14] Forces that had encouraged unity and a desire to enjoy the hard-won peace and stability that were coming into being thanks to the establishment of legal institutions prevented the outbreak of violence for several months. But the hardening of Whig and Loyalist positions set the stage for the Battle of Savages’ Old Fields, which would claim the first South Carolinian casualties of the American Revolution.

The Battle of Savages’ Old Fields

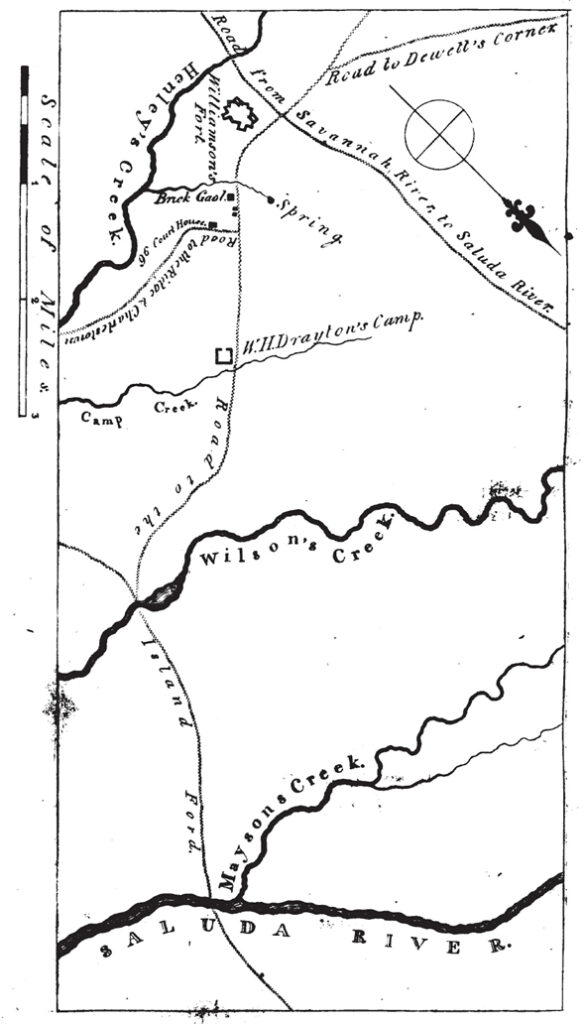

Both Whigs and Loyalists would continue to recruit, organize, and maneuver their forces as they sought mastery of the backcountry. A key document for understanding the battle is Whig commander Andrew Williamson’s report. According to it, on the evening of November 18, having learned of a nearby opposing force of at least fifteen hundred men, a council of war decided to take a position in the “cleared ground of Col. Savage’s plantation, where we could use our artillery with advantage, and there fortify our camp till we should receive more certain information of their strength.”[15] Arriving at their destination the next morning, the Whigs had “about three hours” to establish “a kind of fortification of old fence rails joined to a barn and some out houses” before they were surrounded by “a large body of men with drums and colors.” The Loyalists, enjoying superior numbers, then sought a parley in which they demanded that the Whigs surrender their weapons and disperse. According to Williamson, fighting broke out when, after the Crown forces demanded that the Whigs stay in their defenses, “immediately they took two of our people just by the fort, before my face, whom I gave orders to retake, and a warm engagement ensued, which continued with very little intermission from three o’clock in the afternoon of Sunday [November 19], until Tuesday [November 21] sunset, when they hung out a white flag from the jail.” The jail is a particularly important feature, as it was made of brick and could withstand musket fire. It stood 250 to 300 yards from the Whig fortifications and was likely the center of the King’s friend’s defenses.

On the second Day after the Engagement began, they [Robinson’s Men] set fire to the Fences and old Grass in the Fields all around us, with an Intent to burn up our Fort, which consisted only of old dry Fence Rails, and attack us from behind the Smoak; but the Ground was too wet, and saved us the Trouble of extinguishing the Fire, which we intended to do at any Risk. When they found the Plan defeated, they set to work, and made some Kind of a rolling Battery, behind which they intended to come up and set fire to Col. Savage’s Barn, and to burn us up; but this they afterwards dropt, and set Fire to their Engine themselves.[17]

In his account, John Drayton refers to the “Battery” in this way “the besiegers endeavoured to avail themselves of mantelets, which they had constructed, for the purpose of approaching the fort, and setting it on fire; but not being able to advance them so as to cover their approaches, they were destroyed.”[18]

Thus, as it was clear that sniping away would not drive the Whigs from their fort, the Loyalists sought ways to cross the open fields without suffering severe casualties from rifle and swivel gun fire. However, as noted above, such efforts failed. Conversely, running low on food, water, and ammunition, the Whigs in the fort eventually felt that they would have to go on the offensive in order to break the siege. The letter extract described how five groups of twenty picked men were to attack in five different directions and carry out the following plan:

When they went out each Captain was to reconnoitre the Quarter he was to attack, and then his Fire who attacked at the greatest Distance was to be the Signal for the others, who were each to endeavour making one sure Fire, and immediately retreat into what the other Party called our Fort.

It’s not entirely clear what was going to be set on fire or what was to be done once the fires began—whether that was to lead to a follow-up attack or a strategic withdrawal. According to the abstract, as the sortie was being organized, the Loyalists asked for a parley that would take place early the next morning (Wednesday, November 22), a meeting sought because other Whig militia had risen up and were harassing them.

This parley led to an agreement stipulating that hostilities would end while each side sent unsealed messages to the governor (the authority recognized by the Loyalists) and the council of safety (recognized by the Whigs) seeking direction and the release of prisoners. In the meantime, the combatants could remain embodied. It was also stated that any Whig reinforcements would be bound by the treaty.[19] The treaty also required that the Whigs surrender their swivel guns. Williamson added an explanation of the reality behind what would, at first glance, be a significant error, owing to the importance of the weapons in the Whig’s ability to hold out against superior numbers:

It will appear to your Honor by the articles that we gave up the swivels; but that was not intended either by them or us, for after the articles were agreed on and were ready for signing, their people to the number of between three and four hundred surrounded the house where we were and swore if the swivels were not given up they would abide by no articles, on which the gentlemen of the opposite party declared upon their honor that if we would suffer it to be so inserted in the agreement they would return them, which they have done and I have this day sent them to Fort Charlotte.[20]

Williamson, having described the cessation of hostilities and praised the performance of his men, continued, “Our loss was very small, owing chiefly to blinds of fence rails and straw with some beeves’ hides, &c., erected in the night behind the men who would otherwise have been exposed to the fire of the enemy. We had only thirteen men wounded, one of whom is since dead, most of the rest very slightly. The loss of the opposite party is said to be considerable.”[21] Major Mayson provided more information about the enemy dead, stating that

they had but one man dead, who is a Capt. Luper, and about the same number wounded as ours; by the best information they have buried at least twenty-seven men, and have as many wounded. I am certain I saw three fall at the first fire from our side.[22]

The article accompanying the aforementioned extracted letter states that

Of our Party 14 were wounded, one mortally; of the Enemy it is known several (some say 52) were killed, and many wounded; but Particulars are concealed: That their Loss exceeds ours is not to be doubted, else why should 2000 men make Advances for a Suspension of Hostilities to 500, whom they had a few Days before insolently demanded to surrender?[23]

Thus, while the number of wounded could have easily been several dozens, deaths were likely low, with only two confirmed. Even if fifty were killed, we are still at less than half of what was incurred at Lexington and Concord.

Making Sense of the Battle

Before directly answering the question about why casualties were so few, we must note that knowledge of the battle is almost entirely based on Whig sources. Thus, while Whig troop strength is relatively certain, the number of Loyalists is unclear, ranging from 1,500 to 2,000—numbers based on impressions rather than on actual counts of soldiers. It would have been difficult in battlefield conditions as described above to obtain an exact number. Even so, it seems that the Whigs were clearly outnumbered. In addition, while the Whigs faced logistical problems, it is not clear whether the Loyalists did or not. But considering the lack of organized logistical support, they likely could not keep an army in one place for an extended period. This issue of supply is important, as it means that, unlike during the 1781 Siege of Ninety Six, the Loyalists could not put the Whigs under an extended siege in order to force their surrender—an option that would have limited casualties.

That meant that the only available option in the face of Whig refusal to surrender, the failure of attempts to burn them out, and the lack of Loyalist artillery would be to storm the fortifications. While those fortifications were rather primitive, they offered a great deal of protection and offered clear fields of fire for Whig rifles and swivel guns. Neither side would have had the training to undertake such an attack, which was foreign to the way of warfare on the backcountry, which focused on raids and the defense of stockades—actions carried out by part-time soldiers, typically with families, who sought to win victories while minimizing casualties. And even if they had the ability to mount such an assault, they likely would not have been willing to absorb the high casualties necessary to attempt it. Relations in the backcountry had deteriorated to the point that they were willing to take potshots at another, but assaulting a position and hand-to-hand fighting would be something else entirely.

A battle is not only about the willingness to accept casualties, but also to inflict them. It took years of organization and practice to prepare Massachusetts militia to fire on British regulars. The backcountry had no such preparation and in fact, the white population had been largely unified in their battles with Native Americans, criminal gangs, and the Charlestown political establishment. Moreover, in colonial culture there was a custom of armed protest that implied or even threatened violence without enacting it. Historian Wayne Lee clearly shows this in the case of the North Carolina Regulators, who, despite taking up arms against government troops, had hoped to avoid actual battle. A similar mentality was likely operative here as well.[24] Thus, the battle seems to have in part been fought with a certain trepidation, with a lack of the bloodlust that would later suffuse war in the backcountry.[25]

Conclusion

The Battle of Savages’ Old Fields served as a transition point. Though with some reluctance, blood had been spilled. And yet, the incident with the swivel guns shows that, at least among the Loyalists, there was still something of the old desire for peace and unity. The surrounding of the courthouse by a mob of Loyalists could have led easily to the arrest of Whig leaders and the destruction of their army. Instead, a promise was given and kept of returning the swivel guns, the possession of which during the battle could have led to a victory for the Loyalists. It is unclear what exactly motivated the Loyalists to keep their word and return the cannon, but it would seem that they were serious about a solution that would enable them to go home and live peacefully with the Whigs so long as they did not have to join the Association and repudiate what they saw as their loyalty to King George III.

In contrast, Whig officer William Thomson wrote on November 28, 1775 to Henry Laurens stating that he believed he and his forces were not bound by the treaty, and therefore could move against the Loyalists. In that same letter, Thomson expressed concerns about the difficulty in conscripting militia, noting that some “did as much as to declare themselves King’s men” while others wanted to “subdue the enemies of America, as they observe that those who are not for America, are undoubtedly against it” and that the only way to calm them was by “signifying that the cession of arms was not binding on us.” Thomson also added darkly that “I have some reason to believe that the late mob has privately murdered people in the woods who had been our associates.”[26] The Whig position was clearly hardening. And at around that time, the Whigs assembled an army of approximately 4,000 in the Backcountry.[27]

Such sentiments would play a role in the conduct of the subsequent Snow Campaign, in which overwhelming Whig force was utilized to crush the Loyalists. The bitter experience of battle and being hounded and hunted for their continued loyalty to the crown, embittered and hardened men like David Fanning. They would then be ready to rise and seek vengeance following the British seizure of Charlestown in 1780, leading to the effusion of blood and savagery that Gen. Nathanael Greene described as characterizing the war in the South. That the war would take on that character would have been difficult to predict in the relatively peaceful and unified backcountry before the summer of 1775, but forces unleashed by political changes radiating up from Charlestown led to a transformation in the backcountry. The Battle of Savages’ Old Fields was where the war in the South first became lethal, a violence that would expand exponentially during the later southern campaign.

[1] Nathanael Greene to the President of Congress, December 28, 1780, in John S. Pancake, This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780–1782 (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2003), 73.

[2] This research question was inspired by a talk given by Rick Morris at Ninety Six National Historic Site.

[3] An excellent narrative description of the battle, which helped in the organization of this article, is Marvin L. Cann, “Prelude to War: The First Battle of Ninety Six: November 19–21, 1775,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 76 (October 1975): 197–214. Another helpful narrative is in Jerome A. Greene, Ninety Six: A Historical Narrative (Denver: United States Department of the Interior, 1998), 57–76.

[4] “A Circular Letter to the Committees in the Several Districts and Parishes of South Carolina,” June 30, 1775, in Robert Wilson Gibbes, ed., Documentary History of the American Revolution, 1764 – 1776 (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1855), 107–116.

[5] Nora Marshall Davis, Fort Charlotte on Savannah River and its Significance in the American Revolution (Greenwood: Daughters of the American Revolution, 1949).

[6] See “W.H. Drayton’s and Rev. WM. Tennent’s Commission” Gibbes, Documentary History, 105–106.

[7] “A Fragment of a Journal Kept by Rev. William Tennent,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 225–239.

[8] “Thos. Fletchall to President of Council of Safety,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 123–124.

[9] “Declaration,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 180–181.

[10] “Treaty of Ninety Six,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 184–186.

[11] “Capt. Robert Cunningham’s Answer,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 200. It also might have been the case that Fletchall was drunk. See Cann, “Prelude to War,” 205.

[12] Whigs charged that Loyalist leaders did not actually believe this, but spread false rumors in order to raise their forces. See “Charlestown, December 8,” The South-Carolina and American General Gazette, November 24, 1775.

[13] Cann, “Prelude to War,” 206–207.

[14] Greene, Ninety Six, 12–55.

[15] “Maj. Williamson to Mr. Drayton, Giving an Account of the Siege, Action, and Treaty At Ninety-Six,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 216–219.

[16] John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution: From its Commencement to the Year 1776, Inclusive; As relating to the State of South Carolina: And Occasionally Referring to the States of North-Carolina and Georgia (Charleston: A.E. Miller, 1821), 118–120.

[17] “Charlestown, December 8,” The South-Carolina and American General Gazette, November 24, 1775.

[18] Drayton, Memoirs, 118–120.

[19] “Agreement for a Cessation of Arms,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 214–215.

[20] “Maj. Williamson to Mr. Drayton, Giving an Account of the Siege, Action, and Treaty At Ninety-Six,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 218.

[21] Ibid., 219.

[22] “Major Mayson to Col. Thomson,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 215–216.

[23] “Charlestown, December 8,” The South-Carolina and American General Gazette, November 24, 1775.

[24] Wayne E. Lee, Crowds and Soldiers in Revolutionary North Carolina: The Culture of Violence in Riot and War (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001).

[25] John W. Gordon makes similar points; John W. Goron, South Carolina and the American Revolution: A Battlefield History (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003), 29–31. I have sought to expand them here and am in agreement with most, though I am inclined to believe that the King’s friends did not have the three-to-one advantage deemed necessary for an assault.

[26] “Col. Thomson to Mr. Laurens,” Gibbes, Documentary History, 222–223.

[27] Cann, “Prelude to War,” 213.

Recent Articles

Richard Cranch, Boston Colonial Watchmaker

Announcing the 2025 JAR Book of the Year Award!

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Recent Comments

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

I am not sure I will ever be convincingly swayed one way...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Interesting! Thanks, from a Charlotte NC Am Rev fan.

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

A great overview of that controversial document. I tend not to accept...