The fighting that raged over miles of Massachusetts countryside on April 19, 1775 finally subsided with the approach of evening. Thousands of Massachusetts militia had converged upon retreating British troops as they made their way back from Concord that fateful spring day and the casualties suffered by the redcoats were shocking. Two hundred and seventy-two officers and men were killed, wounded, or captured on the march from Concord. Over ninety militia from twenty-three different communities also fell that day, a majority of them killed.[1]

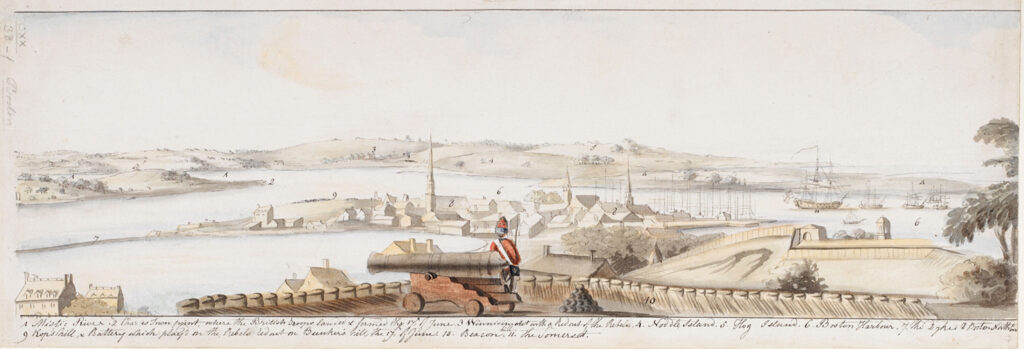

Although the redcoats intended to return to Boston, their commander Gen. Hugh Earl Percy decided late in the day to march to Charlestown, instead. Percy had taken charge of the British force in Lexington when his brigade united with Lt. Col. Francis Smith’s original detachment. Charlestown was located on a peninsula across the Charles River from Boston and Percy expected that the Mystic and Charles Rivers would finally protect his flanks, which had been ravaged by the militia for much of the march. He also believed that the narrow passage connecting the peninsula to the mainland would provide a strong position for his exhausted troops to repulse any further attacks by the militia.

Gen. William Heath, the ranking militia general engaged in the battle on April 19, recognized the danger and futility of advancing onto the peninsula and ended the militia’s pursuit outside of Charlestown. He posted a strong guard on high ground overlooking the neck of the peninsula and ordered patrols to be vigilant all night in case the British attempted to advance from Charlestown. He then ordered the remainder of the militia, numbering in the thousands to, “lie on their arms” below Cambridge.[2]

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress had provided some direction on the structure of the Massachusetts militia over the winter, specifying how each soldier should be equipped and appointing several field officers like General Heath. The appointment of regimental and company officers, and their organization, was done at the local level. This worked fine on April 19 when the objective was simple: attack the redcoats on their return to Boston. But now that the British retreat was over and thousands of militia were gathered outside Boston for what looked to be an extended siege, the logistical challenges of providing for this army of militia became evident. In terms of food and shelter, the troops were on their own until morning. General Heath addressed the issue the next day. He remembered:

How to feed the assembled and assembling militia, was now the great object. All the eatables in the town of Cambridge which could be spared, were collected for breakfast, and the college kitchen and utensils procured for cooking. Some carcasses of beef and pork, prepared for the Boston market on the 18th, at Little Cambridge, were sent for, and obtained; and a large quantity of ship-bread at Roxbury, said to belong to the British navy, was taken for the militia. These were the first provisions which were obtained.[3]

Heath requested that the Committee of Safety, formed the previous fall by the Provincial Congress, which itself was formed in the fall of 1774, send provisions hidden in Concord to Cambridge.[4] They included barrels of beef, pork, flour, rice and peas as well as molasses and rum. The Committee of Safety had taken steps to gather these provisions over the winter. Some of these provisions stored in and around Concord had been moved prior to April 19, but much still remained, hidden away and undetected by the British.[5] Other military stores collected by the Committee over the winter included 2,000 iron cooking pots, 15,000 canteens, 2,000 wooden bowls, 1,100 tents, and various tools such as shovels, spades, pick-axes, hatchets, axes and wheelbarrows. These were also needed in camp.[6] Until they arrived, the quartermaster of each regiment was authorized “to see that proper kettles be provided by loan from the inhabitants for the use of the Provincial troops.”[7]

Aside from supplying the troops, General Heath ordered fifty men to march along the road to Concord the morning after the battle to “bury the dead on the field of battle” and “take care of all the wounded that may be found on the road.”[8]

The last of General Percy’s redcoats were ferried over the Charles River to Boston that same day, but Heath knew they could return at any time. Therefore, he posted two companies of militia on the Charlestown Road to Cambridge with orders to patrol up to the heights overlooking Charlestown Neck. Several smaller guard details were posted on hills between Cambridge, Charlestown, and Boston. A picket guard, made up of twenty men from each regiment, was also established around Cambridge and troops in camp were ordered to keep close to their quarters, ready to turn out at a moment’s warning.[9]

Gen. Artemas Ward arrived in Cambridge in the afternoon of April 20, and assumed command of the troops. Although he was the ranking officer in the militia and had authority over all of the colony’s troops, Gen. John Thomas was given direct command of the militia that had gathered at Roxbury. This was a critical post, for these troops blocked the only land route to Boston.

Ward strengthened the picket guard to 500 men the following night, settling on 320 men on April 25.[10] He also strengthened the other guard details, drawing forty men from each regiment to do so.[11] Earthworks were dug at both Cambridge and Roxbury, as were sinks (latrines). Reveille was set at 4:00 a.m. each day and tattoo at 9:00 p.m. after which a “profound silence” was expected in camp.[12] The men were expected to attend morning and evening prayers each day as well as regimental formations at 10:00a.m. and 4:00 p.m.[13] The purpose of these formations was not specified initially, but aside from daily roll call twice a day to keep track of the troops, one can assume that such activities as practicing military drills and fulfilling daily fatigue duties to keep the camp supplied and orderly were involved. In late June, two hours of daily drill were added to each formation.[14]

Maintaining order and discipline in camp was essential, and given the haphazard nature of the army’s formation, it proved to be an enormous challenge. Frequent gunfire in camp was an example of the lack of discipline, likely the result of lazy sentinels discharging their muskets after duty to clear them rather than going through the process of drawing the musket ball out of the barrel with a ball-pulling tool attached to the ramrod. General Ward had forbidden all such unauthorized firing and instructed some of his guard details to load with loose powder and running ball rather than paper cartridges to make it easier to draw the charges out of the musket to reuse again, but it remained a problem.[15]

While maintaining order and discipline in camp was a challenge, an even bigger challenge for General Ward in the first weeks of the siege was keeping his troops in the field. Planting season was approaching and many of the men assembled in Cambridge and Roxbury were eager to return to their homes to prepare their fields and plant their crops. They had dropped everything to answer the alarm on April 19 and most arrived ill-prepared to stay. With the British tucked back in Boston, the immediate crisis appeared to be over, so many of the militia simply left and returned home. Others stayed, however, and one observer in Cambridge wrote in late April, “I found great numbers of Troops, or rather armed men, in much more confusion than I expected.”[16] Fifteen-year-old John Greenwood, who would soon join a regiment as a fifer, confirmed the lack of order in camp when he arrived in late May. “The army which kept the British penned up in the city at the time,” observed Greenwood, “was no better than a mob, the different companies not being formed as yet, that I could observe, into regiments or divisions.”[17]

Quartering these men was a challenge. Most slept upon their arms with little or no shelter their first night per General Heath’s order, but that would not do for very long. Harvard’s three buildings were used to quarter troops (over 1,500 according to an official count in January 1776), and other public buildings, churches, taverns, and even private homes whose owners willingly opened their doors to the soldiers were used.[18] Initially, vacant homes of Tories who had fled to Boston were not used, but this quickly changed and soon hundreds of soldiers took advantage of such places for shelter. One Connecticut soldier estimated that 250 of his fellow soldiers shared the “finest and largest building in town.”[19] John Greenwood recalled staying in the house of the Episcopal minister, who had gone to Boston with his family:

There we stayed, to call it living was out of the question, for we had to sleep in our clothes upon the bare floor. I do not recollect that I even had a blanket, but I remember well the stone which I had to lay my head upon.[20]

Not all of the army sheltered indoors during this time. Many were provided with tents, but there were not enough to shelter everyone, hence the use of public and private buildings.

The Committee of Safety, realizing that the current militia system would not sustain a siege, on April 23 authorized the recruitment of an army of 8,000 men to replace the militia and serve for the remainder of the year.[21] The committee expected that the bulk of these new troops would come from the militia currently encamped outside Boston, and although a large number did enlist, many did not.

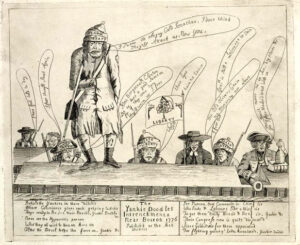

The challenge of raising an army for extended service grew larger two days later when the Provincial Congress overruled the Committee of Safety and called for a 30,000 man Army of Observation comprised of soldiers from all four New England colonies. Massachusetts was to contribute the largest share, 13,600 men.[22] Over twenty-five regiments, consisting of ten companies of fifty-nine officers and men each, had to be raised as quickly as possible in Massachusetts.[23] The Committee of Safety was tasked with drafting a plan to raise and organize this new army. General Ward wrote to the Congress the following day to urge action:

My situation is such that if I have not enlisting orders immediately I shall be left all alone. It is impossible to keep the men here, excepting something be done. I therefore pray that the plan be completed and handed to me this morning, that you gentlemen of the Congress issue orders for enlisting men.[24]

The Committee of Safety could do little to stem the number of departing troops, so it appealed to the surrounding communities for replacements:

As many of the persons now in camp, came from their respective towns, without any expectation of tarrying any time, and are now under the necessity of returning; this is to desire, you would with the utmost haste, send other persons to supply their places, for a few days, until the enlistments are completed, and the men sent down to us.[25]

In other words, with so many militia returning to their homes, there was a great need for new militia to serve in their place until the Army of Observation could be recruited to strength.

General Heath, posted at Roxbury with General Thomas, confirmed the precarious situation the colonists faced early in the siege, noting in his memoirs, “As the new regiments began to recruit, the militia went home, and the camps became very weak; that at Roxbury did not exceed 1,000 men.”[26] Luckily, Gen. Thomas Gage, the British commander, was also concerned about having sufficient troops for offensive operations. Awaiting reinforcements, he kept his troops in Boston, uncertain how to proceed. Recruitment of the Army of Observation continued all May and by the end of the month, a majority of regiments had raised enough men to warrant their commissioning.[27]

Troops from New Hampshire, Rhode Island and eventually Connecticut also arrived to bolster the army outside Boston. They faced their own challenges. Some of the New Hampshire troops had arrived the day after the fighting on April 19. By April 23 there were some two thousand New Hampshire militia gathered in Cambridge. They were in need of organization and leadership as well as blankets, provisions, and other equipment.[28] Like many of the Massachusetts militia, a large number of these New Hampshire men left camp and returned home before April ended, convinced that the crisis had abated. By mid-May about 600 New Hampshire militia remained under the command of Col. John Stark.[29] He appealed to the New Hampshire Provincial Congress in late May for blankets and other supplies for his men:

A great part of the Regiment or Army here, are destitute of blankets, and cannot be supplied by their Towns, and are very much exposed, some of whom, for the want thereof, are much indisposed, and thereby rendered unfit for duty.[30]

Hundreds of troops from Rhode Island, who had arrived in May, faced a similar situation. Thirty-two-year-old Gen. Nathanael Greene, their commander, noted upon rejoining his troops at Roxbury in early June after recruiting in Rhode Island that, “the want of government and of a certainty of supplies, had thrown every thing into disorder.”[31] He added that,

Several companies were so frustrated that they clubbed their muskets [pointed them straight down] in order to march home. I have made several regulations for introducing order and composing their murmurs; but it is very difficult to limit people who have had so much latitude, without throwing them in disorder.[32]

The Massachusetts Committee of Safety estimated on May 23 that nearly 24,500 of the desired 30,000 troops had been raised for the Army of Observation among the four New England colonies.[33] Although short of the goal, this was an impressive number. A return of the Massachusetts troops in Cambridge on June 9 showed 7,644 men among fifteen infantry regiments and one of artillery. Nine other infantry regiments posted at Roxbury amounted to 3,992 men.[34] The troops at Roxbury were supported by over a thousand men from Rhode Island (three regiments) and nearly a thousand men from Connecticut (one regiment). Two of New Hampshire’s three regiments were also with the army by June. Colonel Stark’s regiment was posted across the Mystic River in Medford and Col. James Reed’s regiment guarded Charlestown Neck. Together they totaled over a thousand men. [35] While the Army of Observation was short of its 30,000 man goal at the start of the summer, it significantly outnumbered the British garrison of roughly four thousand within the city.[36]

This advantage in troop strength was offset by a shortage of a crucial item: gunpowder. General Ward and Dr. Joseph Warren wrote to the Continental Congress in early June for assistance:

Our capital is filled with disciplined troops, thoroughly equipped with every thing necessary to render them formidable. A train of artillery, as complete as can be conceived of; a full supply of arms and ammunition; and an absolute command of the harbour of Boston, which puts it in their power to furnish themselves with whatever they shall think convenient by sea, are such advantages as must render our contest with them in every view extremely difficult. We suffer at present the greatest inconvenience from a want of a sufficient quantity of powder; without this every attempt to defend ourselves or annoy our enemies, must prove abortive.[37]

Ward and Warren explained that they had done everything they could to acquire a sufficient amount, but, “the frequent skirmishes we have had have diminished our stock, and we are now under the most alarming apprehension that, notwithstanding the bravery of our troops . . . we shall . . . fall a prey to our enemies.”[38] They urged the Continental Congress to, “warmly recommend to the other Colonies, to send whatever ammunition they can possibly spare.”[39]

The skirmishes mentioned by General Ward involved British efforts to gather livestock and forage from several nearby islands and the colonial army’s efforts to thwart them. There were several small, heated engagements in May that did little to alter the strategic situation, but strained General Ward’s limited supply of gunpowder. To make matters worse, British reinforcements, along with three British generals, William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton, arrived in Boston on May 25, increasing the likelihood of greater British activity before additional gunpowder arrived. This is indeed what occurred on June 17 at Bunker Hill and the limited supply of gunpowder played a crucial role in the outcome of that battle.

Although the provincial troops at Bunker Hill would lose the day—at a tremendous cost for the British—their siege of Boston continued. They did not know it at the time, but three days before the battle, the Continental Congress had voted to place the Army of Observation upon continental establishment. The Congress also appointed a new commander for the newly formed Continental Army. Gen. George Washington of Virginia arrived in Cambridge on July 2 to assume command and oversee the siege that would continue for over eight more months.

[1] David Hackett Fischer, “Appendix Q, British Casualties, and Appendix P, American Casualties,” Paul Revere’s Ride, 321, 320.

[2] William Heath, The Memoirs of Major-General Heath … During the American War (Boston: I. Thomas and E.T. Andrews, 1798), 9.

[3] Ibid., 10.

[4] Charles Smith, ed., “General Orders, April 20, 1775,” The Orderly Book of Colonel William Henshaw of the American Army, April 20-September 26, 1775 (Boston: A. Williams and Co., 1881), 13.

[5] William Lincoln, ed., “Proceedings of the Committee of Safety, November 2, 1774,” and April 17, 1775, Journals of the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the State, 1838), 505, 516.

[6] Lincoln, ed., “Proceedings of the Committee of Safety, April 17, 1775,” ibid., 517.

[7] “General Orders, April 25, 1775,” The Orderly Book of Colonel William Henshaw, 16.

[8] “General Orders, April 20, 1775,” ibid., 13-14; Heath, The Memoirs of Major-General Heath, 10.

[9] “General Orders, April 21 and 25, 1775,” The Orderly Book of Colonel William Henshaw, 13-14.

[10] “General Orders, April 21 and 25, 1775,” ibid., 14-15, 17.

[11] “General Orders, April 21, 1775,” ibid., 14-15.

[12] “General Orders, April 26, 1775,” ibid., 18.

[13] “General Orders, June 14 and May 3, 1775,” ibid., 33, 21.

[14] “General Orders, June 27, 1775,” ibid., 37.

[15] “General Orders, April 30, 1775,” The Orderly Book of Colonel William Henshaw, 20

[16] Peter Force, ed., “Jedediah Hutchinson to Jonathan Trumbull Jr., April 27, 1775,” American Archives Fourth Series, Vol. 2 (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair and Peter Force, 1840), 424.

[17] John Greenwood, The Revolutionary Services of John Greenwood of Boston and New York, 1775-1783 (New York: The De Vinne Press, 1922), 8.

[18] J.L. Bell, The Siege of Boston, Historic Resource Study, Part 1 of 2 (Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 2012), 42-43

[19] Ibid., 47.

[20] Greenwood, The Revolutionary Services of John Greenwood, 8.

[21] “Proceedings of the Committee of Safety, April 21, 1775,” Journals of the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, 520.

[22] “Proceedings of the Provincial Congress, April 23, 1775,” ibid., 148.

[23] “Proceedings of the Committee of Safety, April 26, 1775,” ibid., 152.

[24] “General Ward to the Massachusetts Congress, April 24, 1775,” American Archives, Fourth Series, 2:384.

[25] “Proceedings of the Committee of Safety, April 29, 1775,” Journals of the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, 526.

[26] Heath, The Memoirs of Major-General Heath, 11-12.

[27] Force, American Archives, Fourth Series, 2:763.

[28] “Andrew McClary to the New Hampshire Congress, April 23, 1775,” American Archives, Fourth Series, 2:378.

[29] Nathaniel Bouton, ed., “Colonel Stark to the New Hampshire Congress, May 18, 1775,” Provincial Papers, Documents and Records relating to the Province of New Hampshire, Vol. 7, (Nashua, NH: Orren C. Moore, State Printer, 1873), 474.

[30] Showman, ed., “General Greene to Jacob Greene, June 6-10, 1775,” in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Vol. 1, 85.ed., “Colonel Stark to the New Hampshire Congress, May 29, 1775,” and Force, ed., American Archives, Fourth Series, Vol. 2, 739.

[31] Richard Showman, ed., “General Greene to Jacob Greene, June 6-10, 1775,” in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Vol. 1, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 85.

[32] Showman, ed., “General Greene to Jacob Greene, June 6-10, 1775,” in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Vol. 1, 85.

[33] Force, ed., “Proceedings of the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, May 23, 1775,” American Archives, Fourth Series, Vol. 2, 762.

[34] Richard Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston, and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill…, (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1896), 118.

[35] Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston…, 117-118.

[36] Fischer, “Appendix F: The British Army in Boston: Returns of Strength, 1775,” Paul Revere’s Ride, 309.

[37] Force, ed., “General Ward and Others to the Continental Congress, June 4, 1775, American Archives, Fourth Series, Vol. 2, 906.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

Recent Articles

An Enemy at the Gates: The Tragedy of Abraham Carlile

Siege: The Canadian Campaign in the American Revolution, 1775-1776

The Sieges of Fort Morris, Georgia

Recent Comments

"The Sieges of Fort..."

Thank you for the article highlighting our Fort Morris. A few comments...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

I am not sure I will ever be convincingly swayed one way...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Interesting! Thanks, from a Charlotte NC Am Rev fan.