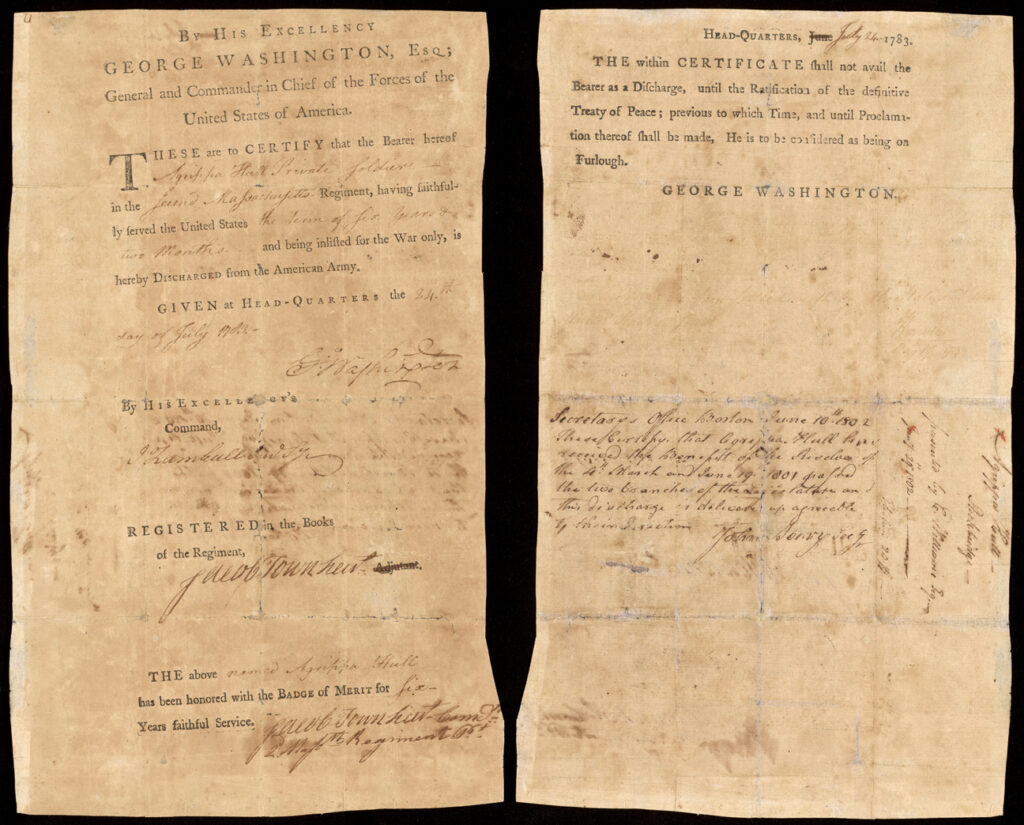

Agrippa Hull was a free black man who enlisted in the Continental Army from Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and served for six and a half years until the end of hostilities. In early 2024 the Museum & Archives of the Stockbridge Library Association acquired, through private sale, Agrippa Hull’s certificate of discharge from the Continental Army, dated July 24, 1783 and signed by Gen. George Washington. The return of this extraordinary document to his hometown enhances the ability of the Museum & Archives to more fully interpret the significance of Hull’s life and service and has a treasured place in our collection of Hull-related artifacts that include his portrait and personal items.

Certificates of discharge were routinely submitted as evidence of a veteran’s qualifying service when applying for a military pension and commonly remained part of the pension records. To find one outside of these archives is unusual, and one belonging to a free African American soldier is rarer still. In addition, his discharge certificate figures prominently in Hull’s story: upon applying for his federal pension in 1818 he was loath to part with the certificate because it contained the signature of General Washington, whom he held in great esteem. Ten years later Charles Sedgwick, a local lawyer who was also Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, wrote a letter of support, requesting that Hull be awarded his pension without the signed documents, because “he had rather forego the pension than lose the discharge.”[1] Sedgwick’s petition was successful and Agrippa Hull received his pension and retained his discharge. The note from Sedgwick can be seen in Agrippa Hull’s pension file.

Agrippa Hull was born free, to landholding parents, in Northampton, Massachusetts, on May 13, 1759. Upon his father’s death in 1761 the family fell on hard times, ultimately losing the title to their land. Hull’s mother, Bathsheba, sent the seven-year-old Agrippa to Stockbridge in the care of Joab Benny (or Binney), whom she knew from when they were both members of Jonathan Edwards’ congregation in Northampton. Between 1755 and 1768, Benny worked as a tanner and purchased upwards of fifty acres of land in Stockbridge, and it is likely that Bathsheba thought her son would have more opportunities there than in Northampton, given her precarious situation.

We know little of Agrippa’s early life in Stockbridge until his enlistment in the Continental Army in May 1777,[2] following which he served for six years; initially as an orderly, or “waiter”, to Gen. John Paterson of the Massachusetts Line, then for four years in the same capacity with the Polish military engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko. With Kościuszko, Hull traveled more widely than most Massachusetts soldiers, being present not only at battles in the northern theater but also at Eutaw Springs in South Carolina. Hull and Kościuszko developed a close friendship, with the former informing the latter’s attitude toward slavery and his firm commitment to abolition.[3]

Upon his discharge from the Continental Army, Hull returned to Stockbridge. He was married twice, first to Jane Darby in 1795 and later, upon her death, to Margaret “Peggy” Timbrook in 1813. Initially he found work as a “laborer”, but soon found employment in a wide variety of occupations:

Agrippa Hull was what we might call, for lack of a better term, an everyman. In town, he knew everyone, went everywhere, and did everything. . . . In addition to serving as a valet and butler in the Sedgwick household, he took on borders and was reimbursed for his expenses by the town (which was responsible for taking care of those who were poor or sick), collected at times a military pension, farmed, boarded horses, bought and sold land, and ran a catering business with Margaret. She baked and also brewed root beer, and he managed the business affairs.[4]

In addition to her root beer, Peggy was especially renowned for her baking, especially gingerbread, and is known to have made wedding cakes for many in Stockbridge.[5] Agrippa, social and a natural raconteur, was held in high esteem in the town and the two of them ran a successful catering business. A bill from a ball he organized in 1799 shows him to have been a successful businessman, having arranged for the room, lighting, refreshments, and entertainment.[6] Along with Elizabeth Freeman (“Mumbet”), an African American woman whose 1781 court case Bett and Brom v. Ashley effectively set a precedent for the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts, Agrippa Hull also worked for the Sedgwick family, one of the most prominent in Stockbridge.

Possibly as a result of his experience as a child when his family lost their land, Hull understood the value and importance of land ownership. Beginning in 1785 with his purchase of half an acre on what is now Goodrich Street in Stockbridge, over the course of the next several decades he purchased, mortgaged, and sold land.[7] By 1829 his property was assessed at $1,213, which encompassed a house, a boarding house, a barn, two horses, two cows, two sheep, several pigs, and eighty-five acres of land. This figure showed him to be, while not as wealthy as the most eminent white families, more prosperous than two-thirds of the white residents in Stockbridge at the time.[8]

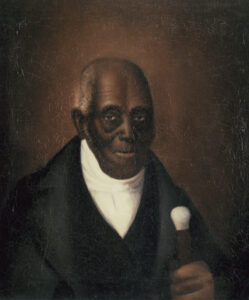

Neither Hull’s descendants nor the staff of the Museum & Archives can trace the path of the discharge document from Hull’s death in Stockbridge in 1848 to its reappearance in a private collection in Pennsylvania. It is unknown how or why a document of such importance to its original owner left the family after his death; however, its value to the history of Stockbridge and, more broadly, to African American history in Berkshire County, cannot be overstated. The certificate of discharge joined several other items relating to Hull that are in the collections of the Museum & Archives of the Stockbridge Library Association. Among them is a daguerreotype of Hull, taken by Anson Clark in his West Stockbridge studio, as well as Clark’s log book which contains the entry, dated March 1844, “Col. Dwight came with Agrippa Hull to have his (Hulls) pict[ure] taken & agreed to pay for it the next time he came over.”[9] An unattributed oil painting, seemingly executed from the daguerreotype image, was donated to the museum in 1947 by Walter Nettleton; and in 1960 Bernhard Hoffman donated a wood and cane chair that belonged to Hull. The Hull collection is important as a record of a remarkable individual, but even more than that, the Agrippa Hull story provides a window into an eighteenth century African American community that is otherwise much harder to trace.

Previous commemorations of the American War for Independence have predominantly focused on battles and generals while saying relatively little about the experiences of “everyday people.” As we begin the 250th cycle of commemorating the American Revolution, it is the mission of many small museums and historical societies to paint a broader picture of revolutionary life, depicting the experiences of women, children, religious and ethnic minorities, and people of color. These small institutions safeguard a multiplicity of stories—often in the form of ledgers, day books, letters and diaries—each of them a valuable part of broader Revolutionary history.

The Stockbridge Library Museum & Archives (SLMA) is grateful to the community, and especially the living descendants of Agrippa Hull, for the opportunity to bring the Hull Certificate of Discharge home to Stockbridge. Readers wishing to view the Agrippa Hull collection are encouraged to contact the curator of the SLMA at le******@cw****.org.

[1] National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC: Pension W.760, NARA R15, Revolutionary War Pensions M804, Roll Name 1363 NARA ID: 300022. 1818

[2] Emilie S. Piper, “The Family of Agrippa Hull,” Berkshire Genealogist 22, no. 1 (2001): 3.

[3] Alex Storozynski, The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2009), 71-74; Gary B. Nash, Graham Russell, and Gao Hodges, Friends of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson, Tadeusz Kosciusko, and Agrippa Hull (New York: Basic Books, 2008), xxx.

[4] Emilie Piper and David Levinson, One Minute a Free Woman: Elizabeth Freeman and the Struggle for Freedom (Upper Housatonic Valley National Heritage Area, 2010), 106.

[5] Historic Northampton, “Expanded Biographies of Both Enslaved People and Free Black People”, www.historicnorthampton.org/srp-expanded-bios.html.

[6] Piper and Levinson, One Minute a Free Woman, 107.

[7] Piper, “The Family of Agrippa Hull,” 4.

[8] Piper and Levinson, One Minute a Free Woman, 108.

[9] Inscription in log-book in the Anson Clark Photography Collection of the Stockbridge Library Museum & Archives, Accession #1999.009.

One thought on “Agrippa Hull: A Revolutionary Story”

Very interesting, Thank you,