Although a genuine folk hero, little has been published about Elijah Clark (often spelled Clarke) beyond well-intended historical fiction.[1] Like his contemporaries Daniel Boone and George Rogers Clark, he should be remembered as an important frontier leader.

Clark’s first biographer, Absalom Harris Chappell, wrote in 1874 that he would never have been known if he had lived on the coast.[2] As an adult, he began as an almost property-less illiterate “cracker,” no different from many Southern frontiersmen. Born in 1742, likely in Edgecombe County, North Carolina, Clark was the son of ambitious backcountry settler John Clark (1689-1764), whose genealogy remains murky.[3] Unlike many patriot leaders, Elijah’s father was a part of his life in a household of numerous siblings.[4] Clark loved hunting and living free as a youth. His daughter described him as handsome, over six feet tall, blue-eyed, and with sandy or chestnut hair.[5]

Clark was one of the first white settlers of Grindal Shoals and Pacolet River in northwest South Carolina, likely on land that belonged to his father.[6] Around 1765, he married Hannah Arrington or Harrington (1745-1827).[7] Ten years later, the Clarks and their then-four children moved to the Ceded Lands of Georgia, today’s Wilkes and surrounding counties. They had no enslaved people and borrowed money from Thomas Waters to make an initial payment on a modest 150-acre tract on what became Clarke’s Creek.[8] The Ceded Lands were intended for families of modest means seeking new lands due to the colonial population explosion and who could provide militiamen to defend the province. The lawless and propertyless were discouraged, as were large, enslaved workforces that would have to be watched and could not legally serve in the Georgia militia.[9]

Unlike other frontier leaders in the Revolution, Elijah Clark’s name seldom appears in public documents. Nothing is known about his involvement in the various class, economic, political, and religious upheavals on the frontier just before the Revolution. America’s war for independence found Elijah Clark and made him a leader. Ironically, he began his public career when, with many prominent backcountry Georgians, his name appeared on a petition against anti-British activities in Georgia on August 26, 1774.[10] Clark and many of these same men, however, quickly embraced the Revolution. They formed a committee for what they called the Chatham District and an ad hoc militia regiment, with companies sent to defend the rebellion in Savannah and on the South Carolina frontier.

These rebels were proactive. They petitioned American Gen. Charles Lee for a war against hostile Creeks to obtain the Oconee River lands. By 1778, the new State of Georgia took orders for their land grants. Two years later, the state assembly passed a settlement act offering incentives for newcomers and restoring the free land headright system that the British government had ended.[11]

Clark became a captain in the state militia by 1776. In that service, he led wagons on the Broad River to supply an expedition against the Cherokees. On July 12, warriors attacked, but he and his men drove them off, and four of the Cherokee were killed. Clark and three of his men were wounded, and three were dead. The following year, he led his men against Creek raiding parties in what Georgia’s 1777 constitution now designated as Wilkes County.[12]

In 1778, as the state had no more than 2,000 armed men, the assembly created two Minute Man battalions by offering generous land bounties to men who enlisted from other states, chiefly South Carolina. Officer commissions went to Georgia residents based on men recruited. Clark became a lieutenant colonel. These soldiers proved an expense the state government could not afford. They were reorganized into six companies, but even then, they had only seventy men. Clark was wounded leading them and was carried from the field during Georgia’s invasion of British East Florida on June 30, 1778.[13]

The King’s Rangers, a Loyalist American regiment led by English-born Thomas Brown, defeated the Georgians. A frontier entrepreneur who survived brutal torture by a mob in Augusta, Georgia, Brown became Clark’s famed nemesis. More has appeared in print on Brown as a partisan leader than any other character in Revolutionary War Georgia.[14]

At the end of 1778, British, Hessian, and provincial troops captured Savannah just after Clark was elected lieutenant colonel of Col. John Dooly‘s Wilkes County militia regiment. But men refused to muster, held divided loyalties, deserted, expected to be paid and supplied, and prioritized protecting their families.[15]

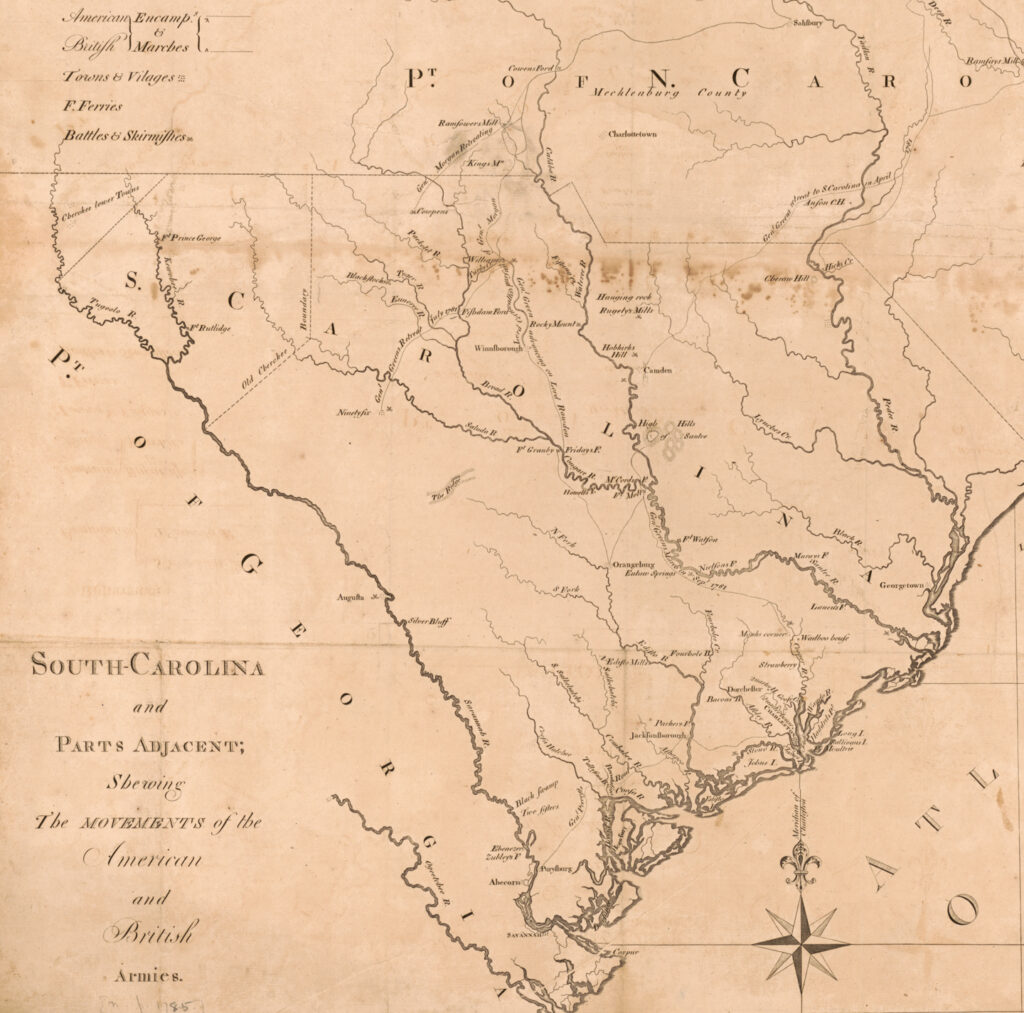

What men Dooly and Clark could muster joined Col. Andrew Pickens and his Upper Ninety Six District South Carolina Regiment in pursuing frontiersmen from the Carolinas who had organized into a regiment to join the British camp then at Augusta, Georgia. They defeated these Loyalists at Kettle Creek, Georgia, on February 14, 1779. Clark commanded the left wing in that battle and had a horse shot from under him. He led a charge across a swamp and up a hill against hundreds of the Loyalists to win the day. Six weeks later and again under Pickens, these militiamen stopped 700 Creek and forty Cherokee warriors from reaching the British army. During the rest of 1779, Clark oversaw the frontier forts.[16]

In the late spring of 1780, the British and their American allies overran Georgia and most of South Carolina. Colonels John Dooly and Andrew Pickens, among others, surrendered their men, who gave up their guns and went home as prisoners of war on parole. Clark and thirty followers then moved to the Carolinas to continue the war. They inflicted heavy casualties against Loyalist American soldiers at the battles of Musgrove Mill and Wofford’s Iron Works. Clark was wounded at Fort Thicketty and Musgrove Mill.[17]

This Georgian was determined to turn the war in the South against the British. He and his small band of refugee militia returned to Wilkes County, where he gathered 400 men, sometimes by force and threats, to attack Thomas Brown and his Loyalist garrison at Augusta in September 1780. Brown, severely wounded in the initial attack, and his men held out under deplorable conditions in Mackay’s trading post. A loyalist rescue force under Lt. Col. John Harris Cruger arrived from Ninety Six and drove Clark’s band from Augusta. Cruger then took charge of the frontier Georgia’s King’s militia.[18]

These Loyalists saw the attack on Augusta as an outrage of a class of propertyless bandit frontier whites. Subsequently, they began a campaign to drive every family who supported Clark or the American Revolution from the Georgia and South Carolina frontier.[19] Cruger had Clark’s men taken in Augusta hanged or turned over to Creek warriors for torture and execution. He ordered Col. Thomas Waters‘ Ceded Lands Loyalist militia to devastate Patriot Wilkes County. The courthouse, many forts, and 100 homes were destroyed. Sixty-eight of Clark’s people were taken as prisoners.

From 400 to 700 people, children, enslaved, female, free, male, and white, followed Elijah Clark in escaping through the Cherokee lands, mountains, and snow with few provisions. After two weeks, they reached safety in today’s Tennessee.[20] Clark wrote to Gen. Charles Cornwallis requesting a truce patrolled by both sides. The British general did not respond; his secretary filed the letter as “curious.”[21]

A Loyalist American corps under British Maj. Patrick Ferguson set out to intercept the Georgians. Clark had previously thwarted this British officer. Frontier militia from four states, including a detachment from Clark, killed Ferguson and annihilated his command at the Battle of Kings Mountain, South Carolina, on October 7, 1780.[22]

The Wilkes Countians also obtained another measure of revenge. In late December 1780, without Clark, who was recovering from near-fatal wounds from the Battle of Blackstock’s plantation, they joined Lt. Col. William Washington’s Continental cavalry and South Carolina militia and attacked Waters’ regiment at Hammond’s Store, South Carolina. The Loyalists were massacred, losing 150 men killed and wounded, with forty taken prisoner.[23]

The Wilkes County regiment was made of refugee fighters, not guerillas. They served in organized paid militia battalions. They famously used the tactics of firing, falling on the ground, and reloading with deadly success.[24] Clark led his band from the front. Col. Isaac Shelby paused in battle to watch “The famous backwoods Titan” in physical combat.[25] In a war where bullets and disease were often fatal, Clark survived battle wounds on at least six occasions, as well as smallpox and mumps.

The notoriety of this Patriot leader cost his family. Loyalists destroyed their home, and Clark’s wife Hannah and their children were forced into a winter wilderness. On at least two separate occasions, he received false reports that his family had been put to death. Hannah had a horse shot out from under her while she was trying to flee with two small children holding onto her back. Despite these experiences and having a horse stolen from her, she showed kindness to the prisoners captured in the last Augusta campaign.[26]

Under Clark’s leadership, the Wilkes County militia fought at Long Cane and Beattie’s Mill. He played a key role in Thomas Sumter’s victory at the Blackstock’s plantation on November 20, 1780.[27] Gen. Daniel Morgan called on these fighters for help, and they came (Clark did not, as he was recovering from wounds suffered at Long Cane). As scouts, they informed Morgan of the approach of Tarleton and his British and provincial troops. They were on the final line with the Continental troops that had to hold for Morgan’s great American victory at Cowpens on January 17, 1781.[28]

Clark led his Georgians in the final recovery of Augusta, a weeks-long campaign in May and June 1781. He had to use his independent, restless frontiersmen in dangerous, monotonous trench warfare. Thomas Brown finally surrendered not to Clark but to Henry Lee and Andrew Pickens, higher-ranking American officers who had taken over command.[29]

By then, Wilkes County was receiving the worst attacks of the war by Cherokee and Creek warrior bands, making starvation a problem as the settlers could not leave their forts to plant crops. In November 1781, Clark led a successful campaign against Creek villages. He also came to the aid of Gen. Anthony Wayne in confining the King’s troops in Savannah. The British evacuated Georgia on July 11, 1782.[30]

Under Col. Andrew Pickens, Clark and 100 of his men attacked Long Swamp Cherokee village in September 1782, the last battle of the Revolution in America. This campaign against Cherokee villages was an unsuccessful attempt to capture Waters and other Loyalists among them.[31]

For his services, Clark received Thomas Waters’ plantation from the state of Georgia.[32] He was appointed the colonel of the Wilkes County militia in 1781 (Colonel Dooly had been murdered by Loyalists the previous summer), commissioned brigadier general in 1786, and made major general in 1792.[33]

Clark fought to secure peace. He served in the legislature from 1781 to 1790 (including service on important committees), on the commission of confiscated and absentee estates, and in the state constitutional convention of 1789. During those years, he was also a commissioner at Georgia treaties with the tribes, erected forts, and won victories in battles against the Creeks.[34]

During that period of post-war Georgia, 1783-1794, the state witnessed its most significant era of growth as families took advantage of the state’s undeveloped frontier lands. By 1790, 40 percent of the state’s population lived in original Wilkes County.[35] The state assembly also awarded bounty lands to the state’s civilians who remained in Georgia for the last eleven months regardless of politics, refugee soldiers, and veterans of the state’s military service. Clark authorized men for these grants and then purchased the certificates to build holdings of thousands of acres, as did other speculators. The state assembly ended the bounty lands system in 1786 because of fraud.[36]

With Clark as an investor, syndicates purchased Georgia’s claims to the western lands that became Alabama and Mississippi from a bribed assembly in the infamous Yazoo Land Fraud of the 1790s, one of the period’s great land grabs. That scheme began with the Combined Society in Wilkes County.[37]

Clark supported progress on this frontier. Although he owned enslaved people, he had a civil rights record. During a battle, he had an enslaved girl, Phillis, sent home rather than seized as booty despite her being owned by a Loyalist named Nesmith. He persuaded the Georgia legislature to give enslaved Austin Dabney, who had fought under Clark, emancipation and a pension, the first such actions done by any government for an African American.[38] As a member of a grand jury, Clark denounced slavery as repugnant to American values of liberty.[39]

Legend has Clark helping to restore the rule of law over vigilantism after the war.[40] He supported and sponsored churches and schools while providing his children with the best education he could obtain.

Although the American Revolution officially ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, in frontier Georgia, clashes between the whites and bands of indigenous native warriors, personal vendettas, and banditry continued. Spain controlled Florida and supplied arms to the Creeks while offering inducements to Americans to settle in its colonies. In the Oconee River territory, rich hunting grounds along the state’s western border became a base for Creek war parties. The resulting raids, which lasted a decade, cost white and Creek lives, frustrated frontier ambitions, and stroked racist paranoia. Georgia obtained the Oconee area by treaty, but the 1790 federal Treaty of New York returned it to the Creek Confederacy. In 1793, the national government cut military aid to Georgia and canceled plans for an offensive war against those villages.[41]

Clark took the initiative to bring peace to Georgia’s frontier. He resigned as a major general in the militia on February 18, 1794. Within a week, he held meetings in Wilkes County to plan an invasion of Spanish East Florida and, reportedly, also West Florida. Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark (no relation to Elijah?) organized a similar venture to invade Spanish Louisiana. French Minister Charles Genêt offered Clark a major general’s commission in the French army and a salary of $10,000 annually to lead an expedition against Spanish East Florida. By August 1794, President George Washington had Genêt recalled. The French government repudiated the expeditions against the Spanish territories.[42]

Clark did not disperse his men but instead took them and their families into the disputed Oconee territory, partly hoping to continue his Florida scheme eventually. They built settlements, formed a council of safety, and wrote their own constitution, forming what historians later deemed the “Trans-Oconee Republic.”

What Clark did on the frontier was one incident in a revolution against the growing power of the new national government. Governor Mathews and the Georgia militia compelled Clark and his followers to agree on September 22, 1794, to abandon their settlements and return to Georgia.[43]

In 1795, Clark again marched to the East Florida border. He abandoned his invasion plans when Gov. George Mathews mobilized the United States and Spanish forces. Two years later, Clark tried unsuccessfully to interest France and Spain in hiring him to organize a defense force for East Florida for a hefty sum of money and the release of his friends still held by the Spanish. He claimed, likely falsely, that the British government wanted to hire him for another Florida invasion and that Thomas Brown was back among the Creeks.[44]

The old soldier’s last years were often bitter. Newcomers’ attitudes towards the earlier frontiersmen like him often did not differ from the contempt shown by the old colonial coastal planter class. Clark’s followers called them “Tories,” slang for the Loyalists during the Revolution. The resulting class and political factionalism continued until almost the Civil War.[45] Local officials and private citizens sued Clark and his comrades over riots and brawls. Stereotypical, restless frontiersmen acted that way, especially those who had never recovered from harrowing experiences in war.

Clark invested across Georgia in different enterprises, including trading with the Cherokees, but mostly involving land. As with many American financiers, the failing national economy brought him down, as did debts from his private military ventures. His land claims were challenged, and much of his property across the state was lost in foreclosure.[46] In 1794, Clark wrote to a friend in frustration that he wanted to move to the wilds of Kentucky to start over, as many of his neighbors had done. He and his friends would rather live “a hunter’s life in the bleak mountains than continue where they are.”[47]

Elijah Clark died in Augusta on December 5, 1799, while trying to resolve his financial difficulties. His old comrade James Jackson had defeated Mathews as governor and reformed the state’s corrupt government after the Yazoo Fraud. He eulogized Clark as “in private life as open, candid and sincere a friend as he was in war a generous, brave and determined enemy.”[48]

In 1801, Georgia named a county for Clark, and a monument to him stands in the county seat of Athens. Today, the Elijah Clark State Park Museum near Lincolnton commemorates his career. Ironically, the site is not the Waters-Clark plantation but on the land of the martyred Col. John Dooly. The state assembly ordered Clark to evict the Dooly’s widow and orphans from the property over a land dispute in 1782.[49]

Clark had prominent descendants. He started the career of his son John, governor of Georgia (1819-1823), for whom a county in Alabama is named, and founder of the Clarkite political faction. Other descendants included grandson Edward Clark, governor of Texas (1861), and great-grandson Alexander McKinstry, lieutenant governor of Alabama (1871). His great-granddaughter Margaret Eliza Hannah Simkins married the famous South Carolina Governor Francis Wilkinson Pickens, the grandson of Clark’s old comrade General Andrew Pickens.[50]

This Patriot hero and his American Revolution have gone forgotten. Public history developed a sanitized version of America’s war for independence of uniformed armies in formal battles, without a place for the South or guerilla warfare. Little of the story of him and his Georgians appears even in the museums of Cowpens and King’s Mountain national battlefields.

Early on, even the story of the war in the Deep South became South Carolina’s narrative, which only makes passing mention of Clark. Georgia had little in print as a scholarly history of its part in the American Revolution until 1957 or, arguably, 1974. The state’s public history has traditionally been a blank between its founding in 1733 and General Sherman’s army marching across it to the sea in 1864.[51]

Researching Clark is challenging. His correspondence was lost in a house fire in 1845, long before Lyman C. Draper came forward to save the history of Thomas Sumter and many of Clark’s other frontier contemporaries. Aside from volume two of Hugh McCall’s History of Georgia (1816), he had no published memoirs of sympathetic comrades to promote his memory, as happened with Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion.[52] Serious research has been done on what Clark sought to do after the war, but it has gone little noticed. That work documents actions not of a fanatic traitor but of a leader created by a frontier revolution that began before the war of 1775-1783 and would continue afterward to, as George Washington envisioned, create an empire that extended to the Pacific coast. Clark’s supporters saw him as a visionary.

Within a few decades of Clark’s death, frontiersman and Revolutionary War survivor Andrew Jackson would reach the White House as a national hero for having acted just as controversially and decisively on the same goals: acquiring the western lands from the indigenous people, and acquiring Florida. Jackson, however, had the support of a pragmatic President of the United States, James Monroe.

[1] See Louise Fredrick Hays, Hero of Hornet’s Nest: A History of Elijah Clark, 1733 to 1798 (New York: Stratford House, 1946) and Janet Harvill Standard, This Man, This Woman (Washington, GA: Wilkes Publishing Company, 1968). Also see Fletcher M. Greene’s review of Hero of Hornet’s Nest, in Georgia Historical Quarterly 30 (December 1946): 358-359. Hays did a valuable service for Clark researchers in compiling “Chronology of Georgia, 1773-1800,” a typescript at the Georgia Department Archives in Morrow. The author acknowledges the help provided by Lee Grady of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

[2] Absolem H. Chappell, Miscellanies of Georgia, Historical, Biographical, Descriptive, etc. (Atlanta, GA: J. F. Meegan, 1874), 34.

[3] Lyman C. Draper notes and Edward Clark to Draper, November 6, 1872, Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina Papers, 1V8, 1V24, Lyman C. Draper Collection, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison. Also, see the research on the Clark family by Douglas C. Tucker on Genealogy.com, www.genealogy.com/forum/surnames/topics/clark/5290/ and USGenweb, files.usgwarchives.net/nc/anson/bios/families41bs.txt.

[4] Robert M. Weir, “Rebelliousness: Personality Development and the American Revolution” in Jeffrey J. Crow and Larry E. Wise, eds., The Southern Experience in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 25-54; Elijah Clark genealogy, Robert Stephen Wilson Collection, Ms2625, box 5, folders 4-6, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

[5] Elijah Clark to Dr. McDonald, December 9, 1794, and Ann Campbell to Lyman C. Draper, April 22, 1872, Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina Papers, 1V8, 1V11, 1V16, Lyman C. Draper Collection.

[6] J. D. Bailey, History of Grindal Shoals and Some Early Adjacent Families (reprint, Greenville, SC: A Press, 1981), 28-30; J. B. O Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History of Upper South Carolina (Greenville, SC: Shannon & Company, 1897), 21, 25.

[7] The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America, The Register Book for the Parish, Prince Frederick Winyaw, 1713-1777 (Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1919), 22.

[8] James A. LeConte, “Transcript Records of the Court of Land Commissioners “`Ceeded Lands’ Later Wilkes, Now Part of Records of Greene Co. Augusta, GA November 19th 1773” (1910), pp. 1, 6, 11, microfilm drawer 154, box 65, Georgia Archives, Morrow; Robert S. Davis, comp., The Wilkes County Papers, 1773-1833 (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1979), 8, 45.

[9] Robert S. Davis, “William Bartram, Wrightsborough, and the Prospects for the Georgia Backcountry, 1765-1774” in Kathryn E. Holland Braund and Charlotte M. Potter, eds. Fields of Vision: Essays on the Travels of William Bartram (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2010), 15-32.

[10] Robert S. Davis, comp., Georgia Citizens and Soldiers of the American Revolution (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1979), 11-13.

[11] Robert S. Davis, “The Man Who Would Have Been: John Dooly, Ambition, and Politics on the Southern Frontier,” in Robert M. Calhoon, Timothy M. Barnes, and Robert S. Davis, The Loyalist Perception and Other Essays (revised and expanded edition, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1989), 290, 293-294; Edward J. Cashin, The King’s Ranger: Thomas Brown and the American Revolution (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1989), 108.

[12] Hugh McCall, History of Georgia Containing Brief Sketches Up To the Present Day, 2 vols. (Savannah, GA: Seymour & Williams, 1811, 1816), 2: 136-137; Hays, “Chronology of Georgia,” 7/2.

[13] Gordon Burns Smith, Morningstars of Liberty: The Revolutionary War in Georgia, 1775-1783, 2 vols. (Milledgeville, GA: Boyd Publishing, 2006), 1:86, 106-107; Allen D. Candler, comp., The Revolutionary War Records of the State of Georgia, 3 vols. (Atlanta, GA: Franklin-Turner, 1908), 2:3, 96, 570, 580, 587; Martha Condray Searcy, The Georgia-Florida Contest in the American Revolution, 1776-1778 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985), 144.

[14] Paul M. Pressly, A Southern Underground Railroad: Black Georgians and the Promise of Spanish Florida and Indian Country (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2024), 59-60; Cashin, The King’s Ranger, 49, 78.

[15] Candler, The Revolutionary War Records, 2:136-137.

[16] Robert S. Davis, Georgians in the American Revolution (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1986), 17-20.

21 Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:211; John Buchanan, The Battle of Musgrove’s Mill 1780 (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2022), 23, 25, 35, 38, 49.

[18] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:211-215; Buchanan, The Battle of Musgrove’s Mill 1780, 59-60.

[19] South Carolina and American General Gazette (Charleston), September 27, 1780; Greg Brooking, From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2024), 167-168, 183, 211; Edward J. Cashin and Heard Robertson, Augusta and the American Revolution: Events in the Georgia Backcountry, 1773-1783 (Darien, GA: Ashantilly Press, 1975), 48-50; Cashin, The King’s Ranger, 118.

[20] J. H. Cruger to Charles Cornwallis, September 28, 1780, Cornwallis Papers, 30/11/64, p. 116, National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew; Elijah Clark to “Governor Campbell,” November 5, 1780, Thomas Sumter Papers, 4VV272-723, Lyman C. Draper Collection; William Stevenson to Susannah Kennedy, September 25, 1780, in The Remembrancer, Or Impartial Repository of Public Events, vol. 11, part 1 (London, 1781): 281; Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1: 213; Robert S. Davis, Thomas Ansley and the American Revolution in Georgia (Red Springs, NC: Ansley Reunion Press, 1981), 26-28.

[21] Clark to Cornwallis, November 4, 1780, Cornwallis Papers, 30/11/4, 20.

[22] Clark to “Governor Campbell,” November 5, 1780; Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:219-221; Buchanan, The Battle of Musgrove’s Mill 1780, 60-61.

[23] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:226-227; Robert S. Davis, “Fighting in the Shadowlands: Loyalist Colonel Thomas Waters and the Southern Strategy,” Journal of the American Revolution, June 11, 2024, allthingsliberty.com/2024/06/fighting-in-the-shadowlands-loyalist-colonel-thomas-waters-and-the-southern-strategy/

[24] Elijah Clark voucher, North Carolina Loose Accounts and Vouchers, vol. IV, p. 58, folio 5, vol. X, p. 94, folio 1, North Carolina Archives, Raleigh; Carolina Price Wilson, comp., Annals of Georgia: Important Early Records of the State, 3 vols. (Savannah, GA: Braid. 1929), 1:166; Lilla M. Hawes, comp., “The Papers of James Jackson, 1781-1793,” Georgia Historical Society Collections 11 (Savannah: Georgia Historical Society, 1955), 17-18; Baika Harvey to Thomas Baika, December 30, 1775, Orkney Island Archives, Scotland.

[25] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:208, 225, 241-242; Buchanan, The Battle of Musgrove’s Mill 1780, 27-28.

[26] Clark to Campbell, November 5, 1780, and same to John Martin, May 29, 1782, Thomas Sumter Papers, 4VV272-273, and Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina Papers, 1V11, Lyman C. Draper Collection; Savannah (Georgia) Republican, September 4, 1827.

[27] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:207-208, 222, 224, 225, 241; Buchanan, The Battle of Musgrove’s Mill 1780, 68-70.

[28] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1: 231-233.

[29] Ibid., 1:245-248.

[30] Clark to ?, November 15, 1781, Keith Read Collection, Ms981, box 4, folder 71, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Collection, University of Georgia Libraries, Athens; Andrew Pickens to Clark, April 3, 1782, Ayer Collection, NL 723, Newberry Library, Chicago, IL; Hays, “Chronology of Georgia,” 69-70; Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1: 256, 259, 263-276, 279-289; Candler, The Revolutionary War Records, 2:435.

[31] Smith, Morningstars of Liberty, 1:276-278; Joshua S. Haynes, Patrolling the Border: Theft and Violence on the Creek-Georgia Frontier, 1770-1796 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018), 85-86.

[32] Candler, The Revolutionary War Records, 3:21.

[33] Robert S. Davis, “The Murder of Colonel Dooly of Georgia: A Revolutionary War Mystery,” Journal of the American Revolution, May 3, 2017, September 30, 2024, allthingsliberty.com/2017/05/murder-colonel-dooly-georgia-revolutionary-war-mystery/; Name File, Georgia Archives, Morrow.

[34] Haynes, Patrolling the Border, 114-115.

[35] Return of the Whole Number of Persons within the Several Districts of the United States (Philadelphia, PA: Childs and Swaine, 1793), 35.

[36] See Marion R. Hemperley, Military Certificates of Georgia (Atlanta: State Printing Office, 1983) and Farris Cadle, Georgia Land Surveying and Law (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1981).

[37] John D. Fair, “Governor David B. Mitchell and the `Black Birds’ Slave Smuggling Scandal,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 99 (Winter, 2015): 257-258. For more on the Yazoo Land Fraud, see Thomas Dionysius Clark and John D. W. Guice, The Old Southwest, 1795-1830 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1989), 68-82; and Helen Clark, The Yazoo Land Fraud (Louisville, GA: Jefferson County Historical Society, 2009).

[38] Robert S. Davis, “Tribute for a Black Patriot: A Pension for Austin Dabney,” Prologue Magazine 46 (Fall 2014): 22-29; Davis, The Wilkes County Papers, 166.

[39] Watson W. Jennison, Cultivating Race: The Expansion of Slavery in Georgia, 1750-1860 (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2011), 121.

[40] Warren Grice, “Nathaniel Pendleton: Georgia’s First United States Judge,” Report of the Fortieth Annual Session of the Georgia Bar Association (Macon, GA: Burke, 1923), 127.

[41] Haynes, Patrolling the Border, 105-154. Also see Caroline C. Hunt, Oconee Temporary Boundary (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Department of Anthropology, 1973).

[42] Frederick Jackson Turner, comp., The Mangourit Correspondence in Respect to Genet’s Projected Attack Upon the Floridas, 1793-’94 (Washington, DC: American Historical Association, 1898), 571, 573, 574, 608, 625, 636, 662, 664, 665, 669, 674, 678, 679; Richard K. Murdoch, “Elijah Clarke and the Anglo-American Designs on East Florida,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 35 (1951): 174-190.

[43] Haynes, Patrolling the Border, 180-183; Edwin Bridges, “To Establish a Separate and Independent Government,” Furman Review 5 (1974): 11-17.

[44] Murdoch, “Elijah Clarke and the Anglo-American Designs on East Florida,” 174-190.

[45] See George R. Lamplugh, Politics on the Periphery: Factions and Parties in Georgia, 1783-1806 (Wilmington, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1993) and Horace Montgomery, Cracker Parties (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1950).

[46] Hays, Hero of Hornet’s Nest, 367n22; Davis, The Wilkes County Papers, 156, 159, 164, 165, 166, 176, 188, 191.

[47] Clark to Dr. McDonald, December 9, 1794, Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina Papers, 1V11, Lyman C. Draper Collection.

[48] Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle and Gazette of the State, December 28, 1799.

[49] Robert S. Davis, “Ambitions, Laughter, Litigation, and Murder: The Legacy of John Dooly’s Egypt Plantation,” Augusta Richmond County History 50 (2) (Fall 2019): 8-32.

[50] Elijah Clark genealogy, Robert Stephen Wilson Collection. Reportedly, Elijah Clark’s stepmother, Martha, was the widow of John Pickens, the uncle (?) of later Gen. Andrew Pickens. Robert A. Ivey, “The Howard Family,” Grindle Shoals Gazette, September 30, 2024: grindalshoalsgazette.com/?page_id=2540

[51] See, for example, H. G. Wells, A Short History of the World (London, UK: Cassell & Company, 1922).

[52] Hugh McCall served under Clark, at least after the war, and was the son of Clark’s friend James McCall. Hunt, Oconee Temporary Boundary, 41; Wayne Lynch, “Captain McCall and Alexander Cameron in the Cherokee War,” Journal of the American Revolution, April 22, 2017: allthingsliberty.com/2013/04/captain-mccall-and-alexander-cameron-in-the-cherokee-war/.

One thought on “Elijah Clark and the Revolutionary American Frontier”

Elijah Clark did sign a protest against corrupt local officials in Anson County, North Carolina, before the war. Nothing is known of anything else that he did during the Regulator troubles.