As the American Revolution morphed into a world war with the entrance of France and Spain, the diplomatic attempts to settle it became more complex. Europe became a hotbed of diplomatic activity, conducted by both state-sanctioned negotiators and freelancers of various sorts, all with their own agendas for negotiations. There was a series of third-party attempts to mediate the conflict, first by Spain and then by Austria and Russia. These proposals could have fundamentally changed the geo-political structure of the United States coming out of the American Revolution. That these activities failed is a testament of the hard work and stubbornness of the American delegation in Paris, who wouldn’t take “no independence” for an answer.

The mediation activities took place from 1779 through early 1782, and the urgency and form of each ebbed and flowed with American fortunes in the war. During much of this period those fortunes were running low, with the victory at Saratoga now years in the past. The greatest of setbacks to the Americans during this period were the double-hit of its worst defeat of the war when the British took Charles Town (today Charleston, South Carolina) and the treason of Benedict Arnold. Finances were also deteriorating precariously, including heavy depreciation of Continental dollars, and funding the war effort was extremely difficult. European powers, especially America’s biggest ally, France, began to look for ways out of the situation, often whether they were consistent with existing treaties or not. One way out that came into the spotlight was mediation.

To no surprise, American Independence was the so-called “Gordian Knot” of these negotiations, the entanglement that Parliament could neither cut nor untie. It was the one intractable issue to any settlement, a non-starter for the British and, as we will see, kryptonite to most mediation proposals. With it on the agenda, nothing could be proposed that would bring all the subjects of the mediation (France, Spain, Great Britain, and the United States) to the table together. King George’s version of the modern “we don’t negotiate with terrorists” was that the British would not deal with the Americans or anyone else supporting its independence. In his mind, to do so would be to sanction their revolt, thereby encouraging further such acts within the Empire. With some of the proposals that came to the mediation table, one must wonder what would have happened to the United States had King George decided instead to take advantage of one of them.[1] He may not have ended up suffering such a total defeat, Great Britain may have kept some footholds in the thirteen colonies, and the United States may have started out looking quite different than the thirteen-colony structure we’re so familiar with today. Almost, but John Adams, and his American co-commissioners, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and (belatedly) Henry Laurens were instrumental in seeing that this didn’t happen.

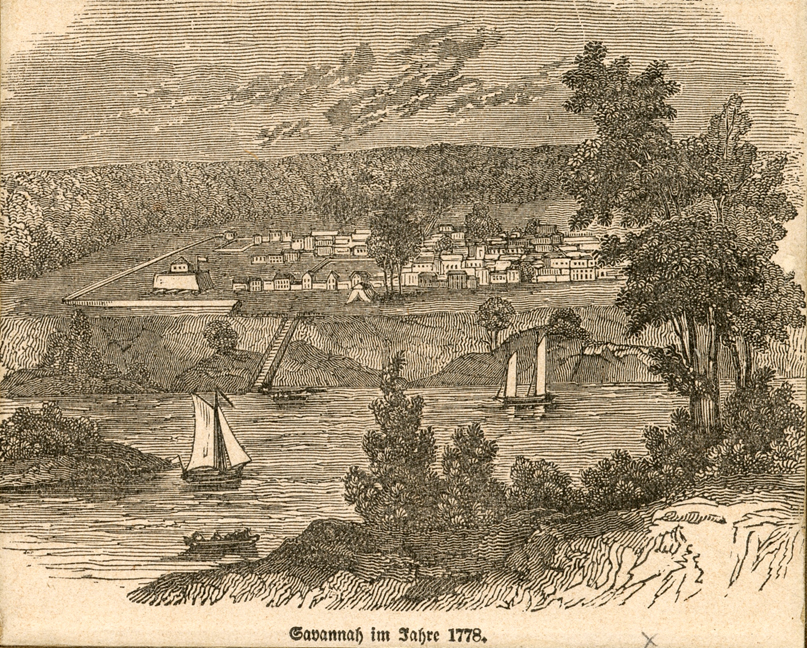

The first attempt at mediation, which would precede the major one, was in 1779, and came from Spain, nominally an ally through its treaty with France, but not well sold on the idea of American independence. After the American agreement with France, Spain had signed a treaty with the French, which in some ways contradicted France’s earlier agreement with the United States. It is in this way that American fortunes began to become entangled with European politics, the result of which was often a subordination of American concerns in the mediation proposals. Under the Spanish mediation proposal, the British would cede Gibraltar to Spain while simultaneously calling the American war to a truce uti possidetis. i.e., the Americans and Great Britain would remain in possession of the territory in North America held by their respective military forces, at the date of the cessation of hostilities.[2] British forces were, at that time, in possession of the ports and much of the interior of North Carolina, South Carolina, and practically all of Georgia. They held New York City and Long Island. They occupied the mouth of the Penobscot River, and thus could claim control of most of Maine.[3] The British, however, were not willing to deal where the Americans involved even peripherally, and in any case were unwilling to part with Gibraltar, so this proposal quickly broke down. However, its tacit backing by the French signaled their wavering attitude about the war, one that would heighten in future rounds of proposals, possibly part of the reason for the delay in France assisting the Americans with troops on the ground.

What further set the stage for France’s uncertainty occurred in 1780, while mediation proposals were still in their infant stages. The French were becoming disenchanted with the adverse events in the war. Ascendant in the French government was a man named Jacques Necker, the Director General of the Treasury. Necker had succeeded a man who was dead set against the French alliance with America, Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot. Necker, an anglophile, also opposed the French intervention in America and approached that opposition under the auspices of getting the country’s fiscal house in order. Late in the summer of 1780 he subjected the French Treasury to a fresh audit. This revealed a serious discrepancy in the accounts which was, according to Necker, a “blow of a bomb … As unexpected as it is unbelievable.”[4] Somehow, without apparent warning or notice, French tax receipts were inadequate to cover the amount needed to sustain the American war. Necker saw no alternative but to float huge additional war loans, which on top of those already in place would create a fiscal crisis. The only sensible course, he concluded, would be to come to terms with the enemy, that being the British.[5]

This attitude began to filter through the rest of the French government. Compe de Maurepas, the aged French First Minister, began to look for ways out, with America’s biggest supporter, foreign minister the comte de Vergennes and King Louis himself both not far behind. In fact, Maurepas would go as far as to send a secret missive to British Prime Minister Lord North proposing a truce. This was forwarded to King George, who promptly vetoed for reasons discussed above. Late in 1780, Necker tried his own message to North, telling him that “You want peace, I want it too,” and suggesting that “a more or less long truce, during which the Warring Parties in America would keep independently what they possess, would be a first reasonable overview.”[6] Staying in character, the King George summarily dismissed this proposal. Necker was undeterred, and was quoted as saying that peace, no matter of what kind, was essential if war prospects did not improve, and that he was prepared to go behind the back of America’s primary advocate in France, Vergennes, and effect a peace without satisfying even the minimum goals of France’s two allies and without regard to Louis XVI’s own honored commitments.[7]

However doubtful, Vergennes still convinced King Louis to continue supporting American independence, stanching the bleeding for the time being. Eventually Necker overreached and was deposed in May 1781, his responsibilities handed to Vergennes. But Vergennes himself, shaken by these events, was beginning to have further doubts creep in, and continued to explore ways out. If the demand of American independence from Britian, the big obstacle in the present world war, could be resolved, the rest would become easy. But how? Mediation provided the potential solution he sought.

As it developed, proposed mediation of the war was a joint effort. The idea was initiated by Catherine the Great of Russia. The British insisted on co-mediation with Austria, which brought Joseph II into the fray. Both had their motives for becoming involved, in terms of prestige and of preserving a European balance of power. The Austrians particularly sought a restoration of dynastic pride, an opportunity to control the fortunes of Europe, and the chance to inflict painful revenge upon the French and Prussians.[8] For Catherine, a peace under Russian mediation would “exalt the reputation of her imperial majesty” with relatively little risk.[9] Neither Catherine nor Joseph II were much concerned with the welfare of the Americans. Indeed, their main goal was to find a way to short-circuit the issue of American independence to the satisfaction of the European combatants. What began, became a long, drawn-out series of diplomatic maneuvers, all tiptoeing around King George’s imperative of not negotiating with an America demanding independence.

The Austrian offer of mediation was tendered to the British by Hapsburg Queen Maria Theresa through her Count von Kaunitz, the Austrian Chancellor, in May 1779. This plan initially did not involve the French in deference to British sensibilities about negotiating with those who favored independence. This situation dragged along unresolved, other than a determination that Vienna would be the venue for the peace “congress” if one could be had (spoiler: it would never happen). Austria alone could not entice the belligerents to accept mediation, but at the same time none were willing to entirely close the door.[10] In December 1779, Catherine issued her formal offer of mediation through Russian Chancellor Count Nikita Ivanovich Panin.[11] The British were initially interested in this offer. The North ministry, through Lord Stormont, British Secretary of State for the Northern Department, stated that peace could easily be arranged if France and Spain would desist from helping the rebels (a big “if”).[12] French support was teetering in wake of Necker’s doings and Spain was never very strong on American independence, but their exclusion could not be arranged, so Britain backed out. The mediators knew the French would have to be involved, but how to do that given King George’s imperative? Though events had a promising start, nothing was clicking. The mediators kept looking for another way.

That way came from the respective representatives doing the detailed work, namely Panin and von Kaunitz. Rather than enter the war on Britain’s side, Panin hoped to bring the Revolution to a halt before the “contagion” of independence spread to the rest of Europe. He thought he could accomplish this best through mediation that would confirm American independence, but contain the damage.[13] Panin’s proposal was predicated on his assumption that the British could never reconquer their rebellious colonies. To secure American independence without wounding British pride, an armistice should be declared, after which the King of France would individually ask each colony if it still wished to retain its independence. In effect Panin was granting the colonies self-determination, or, from an American perspective, partition. The two Carolinas, then under British occupation, were the only provinces he thought likely to choose to return to British sovereignty.[14] While this offer had its flaws, mainly that it still violated King George’s proviso, it was an improvement on the original Spanish scheme of an armistice and status quo in North America, as it left the fate of each American colony to their own choice. Some historians have maintained that, if the polling were done fairly, it may well have led to independence for all thirteen states anyway.[15] But with the British in possession of several of these colonies, such an outcome was far from certain.

Vergennes, already faltering on keeping France’s word to the Americans, considered Panin’s approach. To be sure, he would never propose such a plan himself, and he didn’t want France to give such an unpalatable plan directly to its American ally. He would only accept it if it came from the mediators; He indicated that King Louis had interest in Panin’s proposal and conceded that it tended to resolve the great issues of American independence, possibly a way around that restriction.[16] Digesting Panin’s proposal, Vergennes altered it slightly, suggesting an immediate armistice of at least four or five years but retaining Panin’s idea of separate appeals for independence from each colony. This was his way out. Should some of the “united provinces” prefer to return to the dominion of England, the guaranty of the King of France, under the terms of the treaty, would no longer hold for them except as regards the preservation of peace.[17] Vergennes anticipated that a separate polling, colony by colony, as Panin advised, would have resulted in partition. He was prepared, so it would seem, to turn back to the British the whole of the Lower South in accordance with Panin’s formula.[18]

This approach to partitioning was unacceptable to the British, who again invoked King George’s rule, and blamed Panin for a proposal that did not go far enough. Stormont repeated the conditions: No cessation of hostilities until the colonies returned to their allegiance.[19] He then threw in a couple of sweeteners that would cause great controversy. In exchange for the first item, Stormont offered to turn over to Catherine the country of Minorca, a huge naval base and a warm water port — something Russia had coveted. A plan to award the Hapsburgs the island of Tobago was also proposed. Each country recognized Britain’s offers for what they were, bribes, and were quick to distance themselves. With this as bait, Stormont proposed to turn the clock back to a restoration of conditions in North America as in the treaty of Paris of 1763, modified for conquests during the war; again, a virtual partitioning.

In early 1781, Panin, disregarding the bribes, proposed a congress among all parties to the mediation to take place in Leipzig rather than Vienna as had been earlier proposed by Austria. Again, to such a congress he now proposed that each of the “united colonies of America” send delegates who would be accountable to their respective assemblies and not to Congress. That federal body would remain suspended until each province had ruled on its own fate.[20] Catherine pressed Panin to “make peace … deal with the colonies separately, try to divide them.”[21] Still, the British vetoed this plan on the usual grounds – too much American independence.

Around the same time, good news arrived in London from the battlefields of the American South, and from intelligence assessments suggesting France was out of cash and out of credit. As Necker had intimated, France couldn’t get new loans to finance its war effort. Assuming the French would end the war rather than risk a collapse of their own government, King George and his cabinet changed their minds about the Russian and Austrian mediation and thought Britain could win the war on its own, opting to go for complete victory rather than to settle for a partial success under partitioning.[22] As would later be revealed, they chose wrong.

In the summer of 1781, Vergennes decided to let American Commissioner John Adams in on the mediation. Adams had obviously heard the rumors and had been additionally forewarned by copies of letters he had received from Francis Dana, letters between Dana and French Ambassador to Russia Compte de Verac. Dana had been sent to be American Commissioner to Russia, but his credentials were not accepted by a Russian government not yet ready to officially acknowledge the existence of America, as Catherine scrupulously avoided anything that could be construed as recognition of the United States.[23] Vergennes revealed to Adams the four articles of the mediation that pertained to America, the ones related to partitioning, while “all the rest,” Adams remarked later on, “was carefully covered up with a book.” Those articles were:

(1) The belligerent powers shall leave the decision concerning the fate of the Americans to their own choice.

(2) A suspension of arms or truce shall be concluded among all and everywhere, at least for a couple of years.

(3) It shall be announced to the Americans that each of the United Provinces (colonies) is free during a certain specified time to make known individually to a peace congress its resolution either to return to union with the mother country under conciliatory conditions that have been proposed to them during the course of the war by His British Majesty, or to preserve its independence and own government.

(4) that the means to secure the deliberations of the provinces from all influence . . . be agreed upon with all possible good faith, so that neither fear of the one nor the intrigues of the other can disturb the tranquility of spirits in each Province (American colony).[24]

Adams now registered “very great” objections to the armistice and particularly the third article proposed by the co-mediators. In Adams’ opinion, any truce would be productive of “another long and bloody war at the termination of it,” and a short truce would be especially dangerous.[25] Adams protested in a letter to Vergennes, among his many disagreements stating that:

By this Constitution, all Power and Authority, of negotiating with foreign Powers is expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled. It would therefore be a publick Disrespect and Contempt offered, to the Constitution of the Nation if any Power Should make any Application, whatever, to the Governors, or Legislatures of the Separate States … There is no method for the Courts of Europe, to convey any Thing to the People of America but through the Congress of the United States, nor any Way of negotiating with them, but by means of that Body. I must therefore intreat your Excellency, that the Idea of Summoning Ministers from the thirteen States may not be countenanced at all[26]

Then, late in 1781, came the news of the defeat of the British army at Yorktown. The defeat signaled a death knell for the dreamed-of Congress of Vienna. Even though the British still held Charlestown and Georgia, with all the other things on their plate they knew the game was pretty much up. Peace would now be negotiated under American, French, and Spanish terms. Vergennes, after coming closer to abandoning the American cause than most people knew, was back in the driver’s seat. Upon hearing the news, the Spanish special envoy sent to Vienna as the provisional representative for the anticipated congress, packed up his bags and left, while Kaunitz attempted in vain to keep alive the prospects for an international summit in Vienna.

The fall of the North ministry in London in March 1782 confirmed the new reality and his successor dispatched an envoy to Paris to sue for peace. Kaunitz could do little more than concede the ultimate loss of the Habsburgs’ cherished congress.[27] Now the Americans could demand nothing less than total independence, and the British would have to attempt to salvage what they could from the debacle. But by the time the news of Yorktown reached the Russian capital, Kaunitz’s running mate Panin was no longer in power.[28] The Revolution would be settled not in Vienna or even Leipzig, but in Paris. And so it was, with the preliminary negotiations in November 1782 and the final in 1783.

Years later, looking back on the mediation affair, Adams took pride in having defeated it (though British war fortunes may have been the real death knell). He wrote: “The answer to the articles relative to America, proposed by the two imperial courts, and the letters to the Comte de Vergennes, . . . I have the satisfaction to believe, defeated the profound and magnificent project of a Congress at Vienna, for the purpose of chicaning the United States out of their independence”[29] Adams’ vigorous protest and those of his co-commissioners, along reports of sentiment back in the States, pulled Vergennes back from the precipice, and put American independence back on course. Adams had put a wrench in the spokes of the wheel of mediation, and fortunately for America it soon ground to a halt.[30]

[1] Richard B. Morris, “The Great Peace of 1783,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society Third Series, Vol. 95 (1983), 37.

[2] Samuel Flagg Bemis, The Diplomacy of the American Revolution (Bloomington: Indiana University Press,1957), 172.

[3] Ibid., 181.

[4] Richard B. Morris, The Peacemakers (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 92.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Jacques Necker to Lord North, December 1, 1780, in Lord Mahon, History of England from the Peace of Utrecht to the Peace of Versailles, 1713-1783 (London, John Murray, 1854), Volume VII, Appendix, xiv.

[7] Morris, “The Great Peace of 1783,” 37.

[8] Jonathan Singerton, The American Revolution and the Habsburg Monarchy (Charlottesburg: University of Virginia Press, 2021).

[9] Morris, The Peacemakers, 162-163.

[10] Ibid., 158

[11] Singerton, The American Revolution and the Habsburg Monarchy, 131.

[12] Frank A. Golder, “Catherine II. and The American Revolution,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 21, No. 1 (October 1915), 94.

[13] David M. Griffiths, “Nikita Panin, Russian Diplomacy, and the American Revolution,” Slavic Review, Vol. 28, No. 1 (March 1969), 10.

[14] Ibid., 13.

[15] Ibid., 17-18.

[16] Morris, “The Great Peace of 1783,” 40.

[17] Ibid., 41.

[18] Ibid., 40.

[19] Morris, The Peacemakers,174.

[20] Morris, “The Great Peace of 1783,” 41.

[21] Morris, The Peacemakers,172.

[22] Chris Woolf, “How Russian meddling impacted the American Revolution,” theworld.org/stories/2017/07/04/how-russian-meddling-impacted-american-revolution.

[23] Morris, The Peacemakers,160.

[24] Griffiths, “Nikita Panin,” 13-14.

[25] Morris, “The Great Peace of 1783,” 43.

[26] John Adams to Comte de Vergennes, July 21, 1781, www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/ADMS-06-11-02-0321#sn=19.

[27] Singerton, The American Revolution and the Habsburg Monarchy, 135.

[28] Griffiths, “Nikita Panin,” 18.

[29] Adams to Vergennes, July 21, 1781, footnotes, www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/ADMS-06-11-02-0321#sn=19.

[30] Morris, “The Great Peace of 1783,” 45-46.

3 Comments

Great article Richard, and an important topic. The war’s significance certainly takes on new meaning once we factor in all these outside entanglements and the ambitions of Spain, France, and other European powers at war’s end.

As a Michigander, you might find this particularly interesting, but I’ve done a fair bit of research on the joint Spanish/Indigenous raids against the St. Joseph in what would become Michigan and Indiana, and these are one of the “bargaining chips” that Spain attempts to use to claim the Great Lakes and Trans-Appalachian wests in early plans for the peace agreements. You might check them out: I have a standalone article entitled “Sigenauk’s War of Independence” in the William and Mary Quarterly that I’d be happy to send you, and then a chapter on “Spain’s Bid for the American Interior? The Imperial Contest Over the Revolutionary Great Lakes,” in an edited volume (Paquette and Quintero, Spain and the American Revolution) if you are interested in more. Please reach out–my website is https://www.johnwilliamnelsonhistory.com/

Thank you! This is probably the toughest article of the thirty I’ve written, trying to wade through all the different diplomatic angles and versions of the story. Sure, I’d absolutely be interested in the article you have. Send it along to th*********@sb*******.net. The goings on of the war out in this direction in the country are a neglected topic, and I’m always looking for a new angle to write about. The more I read, the more things I find that I want to dig into further. Your website would keep me busy for a while too!

I’m still trying to sort through where Spain really stood on American independence. I saw a presentation recently on Zoom from the American Revolution Institute Society of the Cincinnati talking about it. I missed much of it, but from the part I saw it sounded like the presenter was saying the Spanish were pretty solid behind it. I have to, as they say, review the videotape, because I’m not so sure. It seems to me that Floridablanca would have tossed us away without much thought (maybe if he got Gibraltar!)

Much of the recent trend in Revolutionary War research seems to place the Revolution as just a part of a world war or even just a British operation campaign of the continuing wars with France. This article reveals that while some monarchs and their ministers saw it that way neither King George nor Revolutionaries such as Adams or assuredly Congress did. Good work to buck trends and keep a balance to history.